13

‘When an individual becomes a person, the beauty hidden in the individual, which is divine, develops; and that development of beauty is personality.’

Hazrat Inayat Khan

On my way to Milan for the start of Teorema, Frederik thought it timely to go via The Hague to meet his Dad.

Floris was a tall, imposing man with an aristocratic head, as well he might, as he was a Baron and his ancestors the Van Pallandts stretched back centuries. The Baron was the Dutch Ambassador to France at the outbreak of World War II, only leaving the embassy when the Nazis were entering Paris. However, as soon the conflict was over, the family returned and Floris came upon a flybill that was to alter his life, announcing a talk on Sufism by one Hazrat Inayat Khan. Previously having had no interest in philosophy, he was drawn by the word he’d not encountered before, ‘Sufism’.

Hazrat, his younger brother Musharaf and his cousin Ali had been dispatched from India by their guru to bring the message to the West. On arrival in France, without any visible means of support yet all being muso’s (Hazrat’s grandfather was considered the Beethoven of India), they found musical employment as Mata Hari’s backing group.

Hazrat played the vina, known locally as struck music. The vina is given a special place in India, as it is considered to be most akin to the human voice. Only after his enlightenment did he cease to play, saying: ‘I gave up my music because I had received from it all that I had to receive. To serve God one must sacrifice what is dearest to one; and so I sacrificed my music. I had arrived at a stage where I touched the Music of the Spheres. Then every soul became for me a musical note, and all life became music. Now, if I do anything, it is to tune souls instead of instruments.’

‘It’s very nice to meet any friend of my son, now what can I do for you?’

‘Frederik said you were the keeper of the papers for Murshid Khan.’

‘That’s correct, he entrusted them to me to formulate into some volumes of The Sufi Message. Is there anything especial you’re interested in?’

‘Breath. The breath. I understand he knew a great deal about the breath.’

He did. The problem is his lectures on breath were usually esoterica, for a few mureeds (pupils), and he was aware how breath could be damaging if incorrectly practiced. His instructions were as much about rhythm as anything else. Also it wasn’t a part of his teaching that was for the general public. His pupils were encouraged not to discuss esoteric matters, which are so easily misunderstood. Even a soul as beautiful as Jesus was criticised for talking of the inherent glory within us all.

There followed a silence. It wasn’t uncomfortable.

‘I understand you’ve met Jiddu Krishnamurti.’

‘Yes.’

‘How did that come to pass?’

‘Federico Fellini showed him some rushes of a film we were shooting when he came to Rome. He asked to meet me.’

‘Did he indeed. And … ’

‘He keeps an eye on me. I see him once a year maybe. He’s so austere, I can’t follow a lot of what he says.’

‘Yes. He does talk a lot about what it isn’t. Yet I hear he is exquisite in person.’

‘Lit from within, is how he felt to me, that first time.’

‘Yes. I know that feeling.’

Another long moment passed. And then he smiled.

‘I suppose I can trust someone who Krishnamurti is keeping an eye on. Repeat after me, it’s a kind of wazifa, something Murshid had us repeat at the start of any talk: “Toward the One, the perfection of Love, Harmony and Beauty. The Only Being united with all the illuminated Souls who form the embodiment of the Master, the Spirit of Guidance.” Now tell me more of why you want to study the breath.’

‘I’m a performer, I studied voice at drama school, yet no one specialised in breathing and I had troubles with the poetic passages in Shakespeare. So I was drawn to the phenomenon of breath. Vanda Scaravelli, who teaches Krishnamurti yoga, has instructed me with the asanas but seems reluctant to go deeply into breathing or pass on what she knows. Krishnamurti doesn’t refer to breathing at all. I think that creative artists can regard themselves as athletes. It all begins with breath, doesn’t it? And nobody seems to give it any thought.’

‘You’re right. Murshid said: “A man who has not gained power over his breath is like a king who has no power over his domain.” It is different in India, both the Brahmin and the Sufis teach their children about complete breath when they are nine years old. It gives them a fuller life in every way. Murshid told me that metaphysically every person has a certain degree of life in them which can be distinguished by his or her breath. And that degree shows itself to the seer as colour, yet even those who have not attained that power of perception can perceive it in a person’s voice. If you practice complete breathing regularly your voice will naturally develop to its fullest potential.’

‘I hope this doesn’t sound silly, yet Kristnamurti has what I think of as a bearing of being. If I could aspire to that it would bring to my work an effortlessness.’

‘We will discuss what Murshid told us as a group and all your questions will become clear. You can make notes today, but later let’s see what you recall. OK?’

‘OK.’

‘It helps to develop listening, just listening; when Murshid came to the West he told me the unstruck music remained with him, even as he was in the roaring streets of Manhattan. The breath will enable you to a different quality of listening.’

‘What are Sufis?’

‘You could say they are to Islam what Zen is to Buddhism. They are the esoteric aspect that develops the one within them. Jelal-a-Din Rumi was one of the earliest known masters to practice Sufism. He is considered the Shakespeare of Persia, the originator of the Whirling Dervishes. It is said the order of Whirling Dervish was based upon his moment of enlightenment when in the ecstasy embodied he turned a full circle in wonderment and his robe left the impression of a circle in the dust where he turned. He was a thirteenth-century poet, yet the dervish order flourishes still.

Learning to Whirl

‘One of the first practices Murshid gave to me he called a Fikar, and this is what I am going to pass on to you. The breath is like a swing which has a continual motion, and whatever is put in the swing swings also with the movement of the breath. Fikar, therefore, is not a breathing practice. In Fikar it is not necessary that one should breathe in a certain way, different from one’s usual breathing. Fikar is becoming conscious of the natural movement of the breath and, picturing breath as a swing, putting in that swing a certain thought, as a babe in a cradle, to rock it. Only the difference in the rocking is that it is an intentional activity on the part of the person who rocks the cradle, and in Fikar no effort must be made to change the rhythms of the breath, the breath must be left to its own usual rhythm. One need not try even to regulate the rhythm of the breath, for the whole mechanism of one’s body is already working rhythmically, so the breath is rhythmical by nature, and it is the very breath itself which causes man to distinguish rhythm.

‘What is important in Fikar is not the rhythm, but the concentration. Fikar is swinging the concentrated thought with the movement of the breath, for breath is life and it gives life to the thought, which is repeated with the breath. On the rhythm of the breath, the circulation of the blood and the pulsation of the heart and head depend, which means that the whole mechanism of the body, also of the mind, is directed by the rhythm of the breath. When a thought is attached to the breath by concentration, then the effect of that thought reaches every atom of one’s mind and body. Plainly speaking, the thought held in Fikar runs with the circulation of the blood through every vein and tube of the body, and the influence of the thought is spread through every faculty of the mind. Therefore the reaction of the Fikar is the resonance of the same thought expressing itself through one’s thought, speech and action. So in time the thought one holds in Fikar becomes the reality of one’s self.

‘For a Sufi, therefore, breath is a key to concentration. The Sufi, so to speak, puts his thought under the cover of the breath. This expression of Rumi’s I would interpret as meaning that the Sufi lays his beloved ideal in the swing of the breath.

‘I feel that’s enough for now. Oh, Frederik tells me you have a set in the Albany. Does Graham Greene still reside there?’

‘I’m not sure. Everyone keeps themselves to themselves.’

‘My wife and I will be making a trip to London next month, God willing, we can look you up if you like.’

‘Yes, that will be great.’

‘I’ll bring some of Murshid’s papers, we can go over them.’

As I went to stand up, he stopped me.

‘Get used to standing up without using your arms, it strengthens your core. The organs used in the respiratory process need to be made strong before we can work on the more delicate aspects of the breath’s magnetism. You’ll be surprised how many times you sit down and get up during a day. It’s a good way to start accommodating your practices into everyday life, tops up your awareness. I’ve enjoyed meeting you, see you in London. Tea at the Albany.’

‘Tea at the Albany. Inshallah!’

‘Inshallah!

Principe di Savoia was one of Milan’s best hotels, and grand it was too. Italian luxury is luxurious. Every possible consideration for their guests to be made comfortable had been implemented. I could really become used to this, I thought, but Pasolini didn’t waste any time and his method of shooting was as quick as Ken Loach, and equally as spontaneous. The part of the Guest, mine, was almost without dialogue and he offered me no direction. Yet after a few days I became aware that he was operating a hand-held camera himself and appeared to be turning over on me when I was unaware he was shooting. Initially I wasn’t sure, yet it became evident it was the case. This was more off-the-cuff than the Poor Cow shoot and it became a game for me to let him think I was unaware when I wasn’t. I did, however, come to the conclusion he was looking for an impromptu happening, unlike usual performing. Not unlike Anthony Newley’s ‘doing nothing’ advice, yet not like ‘nothing doing’ of reality TV. As Cary Grant once told a chum of mine, ‘When it looks so simple, so relaxed, like Picasso, Hammerstein, all confidence and command, but it is really the eventual distillation of all experience.’

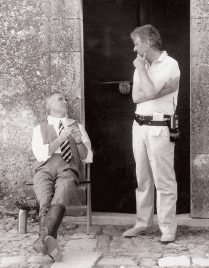

Michael Stevenson

I must confess to eagerly awaiting my kiss with Silvana. It is interesting, an actor’s relationship with his leading ladies. If you don’t love them, and are meant to, you have to find something loveable about them and keep it in mind, and the opposite also applies. Up until Teorema my leading ladies weren’t unknown to me, so the aforementioned situations presented no problem. With Teorema, Silvana in particular, it was a new role I’d been cast in. The ‘divine nature’ of the guest was Pasolini’s creation, and as he rarely spoke to me personally I had no help in that direction. My fellow artists spoke little or no English and the manifestation of the divine nature was a subject I wasn’t about to discuss with even my best chums. In this sense I was alone in Milan. Silvana had an English mother, alive and well in Rome. Her father was a Sicilian, no longer with us. I had little opportunity to get to know Silvana before our love scene and most of what I knew about her life had been furnished by my agent in Italy, Ibrahim Moussa. Her early marriage, before she was twenty, to film producer Dino de Laurentis was a mystery in showbiz circles. He was extremely small in stature and not what you would call physically attractive. The sort of powerful film producer a would-be starlet would set her cap at, yet Silvana was the hottest property of the day before she met him. She had four children, a son and three daughters, the eldest of which was married and had a child of her own. Silvana would have been around forty-five at the time, and a grandmother.

I just had to await the day. I got myself into the all-seeing frame of mind by imagining how it must have been for Christ, who had proclaimed himself a keynote in harmony with every soul. A fact that ended with his crucifixion. The scenes with the father, daughter, son and maid all went fine. The day of the kiss dawned. We only had one take. I am not sure if my intensity shocked Silvana when our lips met, but it was over all too soon. Yet it lingered long in memory, embellished by the tuber-rose aroma that clouded about her.