Different hypotheses regarding the causes of the tragedy of the Soviet nuclear-powered submarine Komsomolets have been stated in numerous articles published in a number of newspapers and journals by representatives of the Navy. Their essence reduces to the following:

a fire occurred as the result of an electrical equipment fault; thereafter, the leakage of the air systems during the fire (hence the introduction of additional oxygen) predetermined the high intensity and swiftness of the fire’s development, which, in turn, rendered fire-extinguishing resources ineffective.

The opinion of the representatives of the Soviet Navy as to the cause of the accident is reflected by the following statement of the Main Naval Staff: “As far as causes bringing about the accident are concerned, numerous technical imperfections in the submarine’s various systems should be named first. These imperfections may be attributed entirely to things left undone by the designers and shipbuilders, and to the impermissible liberalism displayed during the ship’s acceptance trials.”1 They concluded, “Despite the self-sacrificing and technically competent actions by the personnel, it was impossible to save the submarine.”

Any remarks critical of the actions of the personnel and their professional training were met “with bayonets” by the Navy’s “royal host,” which, unfortunately, was not averse to falsifications and obvious slander.

Soviet and foreign experience in designing advanced technical systems shows that there is no such thing as absolutely safe equipment, and, unfortunately, its operation is always associated with the probability of accidents, unpredictable in many cases. Throughout all time, military systems have been created on the basis of the latest scientific and technical accomplishments, and naturally they unavoidably fell within the zone of maximum technical risk. Nuclear-powered attack submarines are the most complex, potentially dangerous, and vulnerable objects in this respect. The especially high danger of fire they present is a consequence of the high levels of power flowing through the compartments, the proximity of combustible materials and fluids to the equipment, imperfections in systems-monitoring conditions in the compartments, and the limited possibilities of fire-extinguishing resources available to a submarine.

At the same time, we cannot agree with N. Cherkashin’s assertion2 that the fire and explosion danger of submarines corresponds to locating a powder magazine in a gasoline storage area, and that submariners live in an environment in which death awaits them at any second. There is no need for extremes either in embellishing the life of submariners or in inflating the horror. Service aboard submarines is harsh and difficult even without these horrors. And no rest areas, swimming pools, canaries, and artificial grass can do anything to make it significantly easier.

Designers creating and testing submarines are constantly concerned with improving the equipment, raising its reliability, and reducing the degree of technical risk, but it is impossible to totally remove the probability of accidents. Under these conditions, the theoretical training and practical skills of every crew member—that is, the professionalism of the people operating the complex and potentially dangerous equipment—have always had the decisive role, and will continue to do so. It is the professionalism of the crew that actually influences the situation and events in a submarine’s compartments before and during an accident; prevents or, contrariwise, promotes the advent and development of an accident situation; and determines the effectiveness of the actions in recovering from the accident. Captain 2nd Rank (Reserve) V. V. Stefanovskiy, the former chief engineer of a naval ship repair plant and currently the senior watchman of a gardening cooperative, was right a thousand times over when he said, “Competent seamen can deal with an accident. Responsible seamen won’t let one happen.”3 For this truthfulness, Vladimir Vladimirovich should not have had to make a career change.

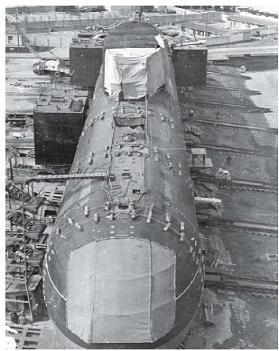

The submarine Komsomolets did not differ in any way from modern Russian submarines currently in operation in terms of the composition of combat and technical resources, including its control systems and its damage control systems. It was accepted in 1983, and in August 1984 it was commissioned.

1. “Roll out” of the Komsomolets

“After its commissioning, the submarine underwent experimental operation for several years. The reliability of the design concepts and the correspondence of its operating characteristics to its predicted performance parameters were validated during this period. The trials were carried out intensively in the most varied navigational conditions, including totally self-contained navigation. As with any other trials, certain problems did occur, but not a single serious breakdown ever occurred. The submarine crew gave a high evaluation to the submarine’s operating properties on the basis of their navigational experience.”4

We should add to this that all of the trials, as well as experimental operation and subsequent patrol duty, were carried out by the first crew under the command of Captain 1st Rank Y. A. Zelenskiy. During the stage of experimental operation, the first crew was supported by the participation of a group of specialists from the USSR Ministry of Shipbuilding Industry. In 1988 the submarine was recognized as an outstanding submarine, and it was awarded the name Komsomolets. Captain 1st Rank Y. A. Vanin’s crew was the second crew of this submarine, and the cruise that began on February 25, 1989, and ended in the tragedy on April 7, 1989, was their first independent cruise.

First, while giving credit to the individual heroism and bravery of the crew members, we need to objectively evaluate their actions, as a crew, during the accident. This is imperative if repetition of such tragedies are to be avoided in the future. Wrong and biased conclusions based on imaginary or real imperfections of a submarine will only obfuscate the real issues. In this case I must agree with Vice Admiral Y. D. Chernov’s opinion5 that any distortion or toning down of information, even out of the most humane motives, is immoral in relation to submariners, who, now and in the future, are called to serve patrol duty.

Second, we also need to objectively examine the “numerous technical imperfections” alleged to be present in this submarine and, in the opinion of the naval leadership, helped to bring about the accident. And third, we need to describe what measures are being undertaken or should be undertaken to raise the reliability of submarines currently in operation.