Bhutto’s government was deposed in July 1977 by the Pakistani military, led by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, after disturbances following a general election which opponents of the Pakistan People’s Party claimed had been rigged. Bhutto was charged with ordering the murder of a political opponent, Ahmed Raza Kasuri. After receiving an appeal from Bhutto’s daughter, Benazir, then under house arrest, Trevor-Roper found a British barrister willing to represent her father, and pledged to underwrite the lawyer’s fees. Returning from a month’s visit to Pakistan, the barrister later reported that there was ‘absolutely no hope of justice’ for his client. Once Bhutto had been sentenced to death, Trevor-Roper appealed to the Pakistani Ambassador for clemency, urged the Leader of the Opposition, Margaret Thatcher, to make representations to the Pakistani authorities, and in an article for the New York Times (24 June 1978) predicted ‘grave political consequences’ if Bhutto underwent judicial assassination. ‘His death could lead to the end of Pakistan and a further defeat for the West.’

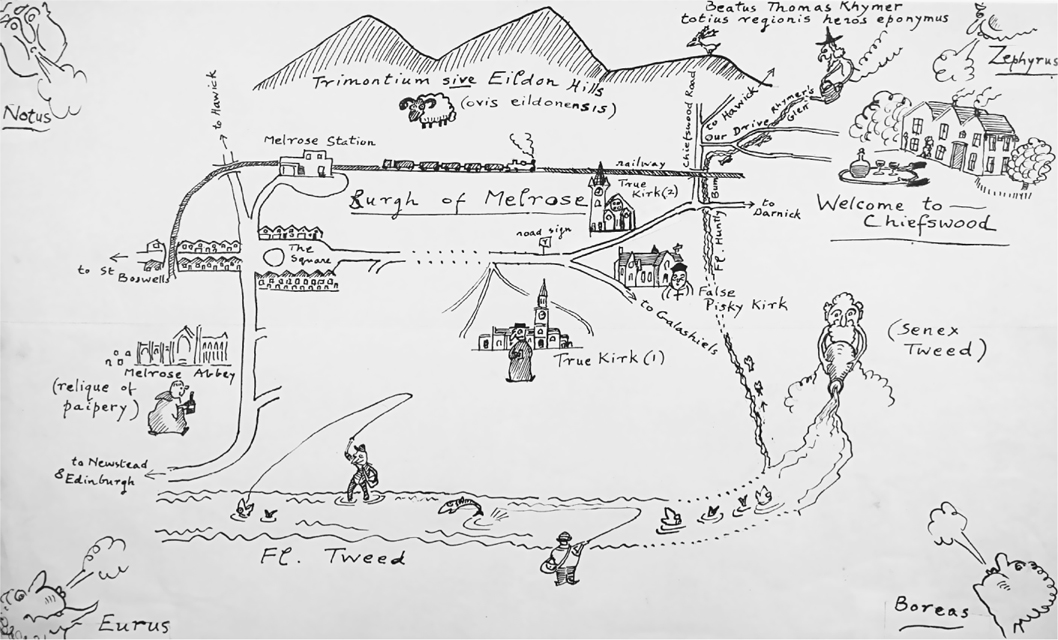

Trevor-Roper’s map for visitors to Chiefswood.

Chiefswood, Melrose

My dear Blair

Thank you very much for forwarding those letters. You are a friend indeed. I hope you are better. I don’t like to think of you stuck in Oxford with only a virus for company, and a new term upon you. The Thames Valley is healthy only to those who are born in it: they live in it, long and slowly, like carp battening in stale ponds or primeval reptiles somnolent in the slime. We brisker fish require more bracing streams. I have never been well in Oxford.

Here I have been very active since we returned from Switzerland. Mainly I have been struggling on behalf of my poor friend Z. A. Bhutto. I wrote to Mrs Thatcher, who has taken some action. I also wrote to my two MPs, who conveniently represent the other two parties. David Steel has not replied,1 but Evan Luard2 has been helpful and reports that diplomatic representations have been made at all levels, through the British Embassy in Islamabad, to the head of the Pakistani Foreign Office (who was in London on a visit), and to General Zia personally. I also wrote to the Pakistani ambassador; and I wrote a 2500-word article which was to have appeared in The Times on Monday. But then, on Sunday, I had cold feet. I rang up the Times and stopped its publication.

Cold feet? No, a crise de conscience. On Saturday I received from the Pakistan Embassy the complete judgment in the Lahore trial. It is very long: 134 pages closely printed. I spent all Saturday reading it carefully; and the result was that I decided that I could not publish anything until I had discussed this document with the QC who, at my request, had gone out to Pakistan and reported that the trial was rigged and the verdict predetermined. And I cannot discuss it with him at present, for he is in Hong Kong.

The trouble is, on the evidence so far available, I think that Bhutto may have ordered that murder. Admittedly the evidence may have been extracted by torture. Admittedly the court may have hampered the defence and favoured the prosecution. Admittedly the prosecution case was public while the defence was heard in camera. Admittedly the trial may have been political. But having read this long document I am very uneasy. There is too much apparently concrete and converging evidence that Bhutto, if he did not positively order the murder, at least connived after the event and prevented an investigation.1 And if this is so, certain grave consequences are entailed.

I have often asked myself at what point Hitler could and should have been stopped, and my answer has always been, after 30 June 1934—i.e. after the so-called ‘Roehm Putsch’, when the Chancellor of Germany, having at his disposal the police and the judiciary of the country, preferred to get rid of his political rivals by assassination. At that moment, I reply, the German establishment, which had hitherto accepted his power as legal, should have rebelled, since it had become plainly illegal, and should have removed him, necessarily, by force. But this requires us to define the force to be used. It could only be the Army. And the Army having no constitutional power to rule, there would necessarily have been, for a time, de facto military rule. Those who will the end will the necessary means; and so it has always seemed to me that an unconstitutional military interregnum would have been a political necessity if the rule of law were to be restored in Germany.

What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. If Bhutto was so corrupted by power that he did in fact order the murder of Ahmad Ruza Kasuri, then, by parity of reasoning, that not only justified but required action by the legal establishment, and this in turn required the intervention of the Army and a temporary military administration. The rule of the Army may then, like that of Oliver Cromwell, have acquired a momentum, and a direction, of its own, and its promise of a rapid return to normality may have been betrayed, or at least deferred; but that is another matter. Essentially, my argument about Nazi Germany obliges me to admit that General Zia was justified—always assuming that Bhutto had used the forces of government to carry out a political murder.

On this factual question therefore—whether he did or did not order the murder—every other question depends; and until I can feel certain about it, I must fall silent. Fortunately, there is now more time than I had thought, as the appeal is not to be heard till 5 May.

I have just been attending a very melancholy function: the sale of the books in the Signet Library in Edinburgh. This is a marvellous library, built up into a great cosmopolitan collection in the late 18th and early 19th century, above all by Macvey Napier1 and David Laing;2 and it is marvellously housed in a magnificent building in Parliament Square. But what is learning, what is literature, what is cosmopolitanism, what are the names of Napier and Laing to the modern Writers to the Signet? Before going to view the books on Tuesday, I had lunch in the New Club,3 the so-called ‘exclusive’ club which has just blackballed Ludovic Kennedy.4 It is now dominated by Edinburgh WS. (An aristocratic friend told me once that his stepfather had resigned from the club because it had started admitting lawyers. Now the two chief grumbles of the Edinburgh beau monde, such as it is, are that lawyers have occupied the New Club and that dogs have got into the residential gardens of the New Town). As I looked round at those lean, mean, foxy faces, with their dry skin and narrow eyes, I saw in them incarnate the spirit of the new Scotland, the re-parochialisation, the return, after the Enlightenment of the 18th century, to the introversion of the 17th. Now the wretches are rubbing their hands with glee at the vast sums they are making at the sale. For the prices fetched were absurd—sometimes ten times the estimate. Real cosmopolitans were there, as buyers. I went in the hope of buying two volumes of Vanini, which went at £480, and Tho. Dempster’s de Etruria Regali which is not being sold until tomorrow; but I shall not now bother to go tomorrow.

yours ever

Hugh

PS. 18 April. Mrs Stowell1 has just telephoned to tell me about John Cooper’s death.2 A great blow; and how strangely similar (as reported to me) to that of his Master, McFarlane.3