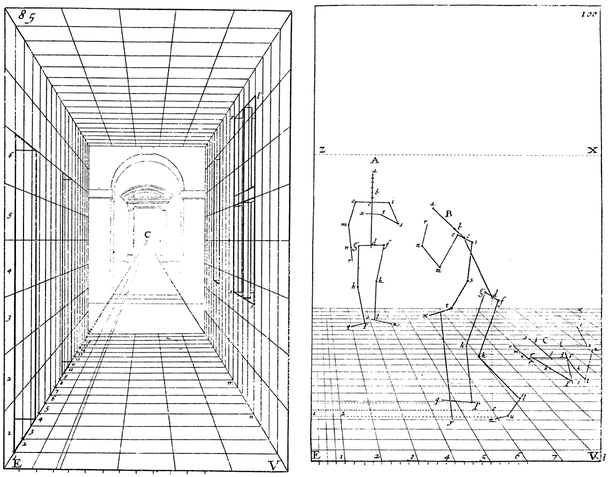

Figure 6. Abraham Bosse, from Desargues’s Universal Method, 1643

This chapter will establish how, in the nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries, a radically different, ‘modern’, vision of humanity emerged in Western culture. This emergent figure gave rise to a new imagination and representation of the human subject within the European avant-garde. This chapter will consider Cubism in particular by considering the context for its emergence and the significance of the challenge it issued for overturning existing models of representation such as perspective. Cubism, however, certainly did not exist in a cultural vacuum. In response to reactionary claims in the early 1920s that writers no longer engaged in traditional mimetic conventions, Virginia Woolf suggested that ‘on or about December, 1910, human character changed’.1 Regarding architectural concepts of space Siegfried Giedion later wrote: ‘Around 1910 an event of decisive importance occurred: the discovery of a new space conception in the arts.’2 Reflecting upon modernism, Henri Lefebvre claimed: ‘The fact is that around 1910 a certain space was shattered’,3 whilst Michael Baxandall contends: ‘The extraordinary thing that happened in 1906–12 was an abrupt internalisation of a represented narrative matter into the representational medium of forms and colours visually perceived.’4 We have already noted Charles Péguy’s suggestion that the world had transformed more in the 30 years prior to 1913 – even without the knowledge that World War I was fast approaching. Although Hubert Damisch offers a wry ‘smile’ at the supposed sudden ‘fall of the reigning paradigm’,5 he nevertheless admits that a profound change occurred. Damisch identifies a shift from nineteenth-century pictorial structure, reflecting a transformation in the ordering of human knowledge. All these writers, whether within Modernism or considering it retrospectively, contribute to a sense of a profound shift in ‘human character’ and a concept of subjectivity imagined through how it constructs, and is constructed by, the environment in which it exists. Indeed, this ‘new’ figure emerged from instability in the nineteenth-century culture, whereby Foucault writes that ‘man’ became a new object of knowledge.6 A simultaneous and massive change affected both the human subject and its environment through technological, socio-political, philosophical and scientific shifts. It is through representation that a shift in cultural thinking – specifically here the interrelation between subject and world – can be identified at an historical moment. This chapter will proceed to consider a number of cubist works to illustrate this modern reconfiguration of the subject.

In modernity, the imagination of ‘time’ is increasingly important to representation and the urgent concern of artists. Embedding time within the canvas’s space to represent modernity’s new conditions had ideological implications. For example, the dynamic relation of a person to time was crucial for a philosopher such as Henri Bergson. However, this consideration of time had been consistently omitted from Western thought. Space and time are two concepts that have been forcibly cleaved from their experiential ontological relation within representation, just as human subjectivity has been imagined independent of its environment. Accordingly, Lefebvre argues that the Western production of a particular ‘classical’ space – both conceptual, abstract, philosophical and representational – was ‘shattered’ by the arrival of dynamic temporality within spatial representation. This section observes a transformation that allowed the formation of a radical concept of the self as simultaneous with the environment.

For Woolf and Lefebvre, ‘time’ intersects the traditional relationship between subject and space. Neil Cox sees Bergson’s philosophy of Being and temporality as having ‘a profound effect on modernist literature and the creation of the “stream of consciousness” novel developed by Marcel Proust, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf’.7 Literature placed a new emphasis on narrative temporality and simultaneity, whilst in the plastic arts, representation underwent a shattering, or rather a ‘reimagination’, of traditional perspectival and geometric space. Such a static pictorial regime occluded the modern condition of temporal dynamism and simultaneity. Lefebvre explains that ‘[t]he pictorial avant-garde … were busily detaching the meaningful from the expressive’, and therefore developing ‘the beginnings of the “crisis of the subject” in the modern world’.8 Representing the subject in crisis meant a confrontation with classical representation and its perpetuation of an inherent pictorial regime. The modernist challenge to existing forms of knowledge through representation was nowhere more fervently articulated than in France, where Cubism emerged as a coherent force.

Cubism’s challenge to established visual conventions engaged it in the cultural storm that surrounded the ‘crisis of the subject’. The canvases of the salon modernists, including those of Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Jean Metzinger, Léger and Gleizes, became caught up in streams of political turbulence, as art participated in cultural transformation through the re-imagination of the subject. However, whilst Lefebvre’s characterisation of the shattering of space specifically referred to Picasso, neither he nor indeed Braque had any significant relationship to the wider public. Their work, under the patronage of Daniel Kahnweiler, was largely confined to a hermetic, studio-based, painter-dealer-collector relationship. Cubism, as the French public knew it, largely belonged to those salon artists emerging out of Impressionism, post-Impressionism and Fauvism, influenced by the work of Gauguin, Courbet, Matisse and Cézanne.9 It emerged from literary influences, in particular Symbolism, and engaged, if tangentially and inaccurately at times, with Bergson’s thought.

Cubism’s unfolding from public Salon exhibition became a cultural phenomenon. As such, it was subjected to political debate regarding ‘social order’. It represented figuration after an epistemic transformation regarding the relations of experiential perception and representation that profoundly offended reactionary politicians. Even though the cubists submitted for exhibition through a process of gallery submission in which, as Baxandall argues, the ‘Black’ galleries ‘had much the same structural and institutional character as the official Salon [and] were concerned to point to their long pedigree’,10 they had provoked outrage in previous exhibitions in 1911. In 1912 the Salon d’Automne exhibition caused debate in the Chambre des Députés regarding the appropriateness of the public exhibition of cubist work:

I hope that you will leave the place as disgusted as many people whom I know … do I really have the right to give the use of a public monument to a band of crooks [malfaiteurs] who behave in the world of arts in the way that gangsters [apaches] behave in ordinary life.11

M. Lampué, a Parisian municipal councillor and ‘elder statesman’,12 addressed the issue of allowing public exhibition of such works to Léon Bérard, the Under-Secretary of State responsible for the arts: ‘It is absolutely inadmissible that our national palaces should be used for manifestations of such an obviously anti-artistic and anti-national kind.’13 However, it was not only conservative factions that objected to the apparent threat to national integrity. The socialist Jules-Louis Breton remarked that cubist paintings consisted of ‘jokes in very bad taste’, painted by a large proportion of foreign artists. He subsequently requested the political censorship of work that evinced the ‘anti-artistic’ and ‘anti-nationalistic’.

Following Marcel Sembat’s defence of Cubism, believing that it was not the Chambre’s place to dictate over artistic freedom, Bérard agreed to the principle of non-intervention, though he later attempted to exert his influence on Frantz Jourdain, President of the Salon d’Automne, to eliminate foreign, and especially cubist, painting. Gleizes later recalled that

It was against these painters – and against them exclusively – that the attacks of the public authorities, provoked by the Parisian press and by pressure from the academies, were aimed. The Conseil Municipal de Paris threatened the Salon des Indépendants, where Cubism had begun, with its thunderbolts.14

Gleizes notes that, in defence of Cubism,

Marcel Sembat spoke: ‘The Salon d’Automne this year [1912] has had the glory of becoming an object of scandal, and this glory it owes to the Cubist painters!!!’ That was how Sembat’s speech began, and this speech is an important event in modern history. For the first time in a parliament a question concerning the moral order, free of any material interest, a question of concern to the needs of the spirit, was raised. For the first time, the legitimacy and superiority of the appearances of unofficial art were openly proclaimed.15

By placing cubist paintings ‘in a dingy room and a cluttered display’,16 the Salon sought to control any controversy. Despite Francis Picabia’s election as an associate member to the Salon, the committee limited the visibility of the work. Nevertheless, it was the little side room, rather than grandiose public display, that produced the furore. Gleizes commented that Frantz Jourdain had tried to quell the rising debate by including more traditional portraiture from the Société des Artistes Français in the adjacent room. However, this gallery effectively became a waiting room for visitors queuing to see cubist canvases. A matter of representation erupted into political argument, public spectacle and media sensation. In response to the attacks upon them, the initially rather diffuse group of painters associated themselves under the initially derisory, and conceptually otiose, term ‘Cubism’.

Gleizes’s paintings, however, were already embroiled in controversy. 1911 had been the year Cubism first attained international notoriety, and the public storm of 1912 had continued this first response. In the Salon d’Automne of 1911, Gleizes remembered:

The opening-day crowds quickly condenses into this square room and becomes a mob … they interrupt one another, protest, lose their tempers, provoke contradictions; unbridled abuse comes up against equally intemperate expressions of admiration; it is a tumult of cries, shouts, bursts of laughter, protests.17

John Golding observes: ‘for the general public, who did not know the achievements of Picasso and Braque, the work of Delaunay, Léger, Gleizes and Le Fauconnier represented cubism in its most advanced and developed form.’18 Indeed, Cox comments that they were the ‘only Cubists’.19 That the painters occupied room eight in 1911 was partly due to the organised presentation of their canvases. Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s and Roger La Fresnaye’s influence on the hanging committee furthered their position. The exhibition in Room 8 exceeded the sensation of the cubist presence in Room 41 at the Salon des Indépendants, as it ‘generated more scandal and ribald mockery’.20 The critic Armand Fourreau complained of the ‘unquenchable thirst for noise and publicity: basically that is the true evil which rages violently at this moment above all amongst young painters’.21 In some ways, the art market had facilitated this ‘outrage’, for these painters were without institutional or dealer security, and their ‘evil’ was in part self-promotion. With the decline in direct state influence, the rise of the private art market, the dealer-critic system and Salon exhibitions,22 avant-garde painters had courted publicity since the mid-nineteenth-century, and Cubism’s shock was a consequence of those conditions. Gleizes reflected that Cubism’s notoriety perhaps spread even more rapidly as a consequence of the ‘violence’ of its enemies’ preventative efforts: ‘Public opinion throughout the world was occupied with Cubism … excited by the new appearances that were being assumed by painting.’23

Cubism’s challenge, and its contribution to modernity’s ‘crisis of the subject’, lay in its radicalisation of visual form. Although its subject matter was often unremarkable, even banal, this only highlighted the profound effects of its form. Like Realism, the ‘everyday’ became the object of attention. Cubist experiments extended to even the most mundane cultural object through its re-presentation. It investigated the embedded, spatial visual codes and conventions upon which systems of Western knowledge were based. To undermine these was to undermine culture itself with the proposal of a new, modern visuality based on time, simultaneity and instability of perception. Cubism’s critique of cherished, stable systems of visual knowledge makes the inflamed outrage of its critics a more understandable response.

We might argue that Cubism made an earlier mode of radical thought accessible to an increasingly democratic age. For example, in many ways, its challenge was inherited, indirectly, from John Locke’s work on the relationship between seeing and knowing, the limits of visual language, and the notion that human vision is not ontologically veridical. Indeed, as Baxandall writes, ‘the issue of what a picture represents did not originate in 1906’.24 Baxandall cites Newton’s idea that colour exists as ‘sensations in the mind’ alongside Locke’s thought that visual perception is not inherent or axiomatic, but must be learnt according to rules. For Baxandall, Locke and Newton symbolise a divergence of thought in the seventeenth-century: ‘a series of shifts in thinking about perception in general that directed many people’s minds towards the subject in perception, towards the perceiver’.25 Indeed, William Molyneux’s letter of 1688 to Locke, written after having read an extract of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, in some ways initiated the questions Cubism later visually introduced to a wider culture. Molyneux’s conundrum subsequently preoccupied such thinkers as Berkeley, Leibniz, Voltaire, Diderot, Helmholtz and William James. The question posed was whether a man born blind who learned to recognise a sphere and a cube by touch would be able to recognise them if suddenly given sight.26

Locke’s work concerned empirical ideas on the processes of knowledge.27 Rather than the classical understanding of meaning as something innate, or ‘rational’, as in the work of René Descartes, here knowledge is produced from sensory experience. Contrary to rationalism’s positing of geometric axioms or innate categories as the fundamental principles of knowledge, Locke proposed an understanding of the mind as a tabula rasa upon which experience forms the subject. He and Molyneux agreed that a person suddenly given sight could not distinguish objects, as the conceptual models needed for cognitive recognition would not have been developed. The chaos of sense impressions therefore could not be decoded into a coherent three-dimensional model that constituted visual perception and symbolic language. The newly sighted subject may therefore receive sensation but not the conceptual framework to order, code and understand it; Locke recognised that opticality is not direct conscious knowledge. George Berkeley arrived at Locke and Molyneux’s conclusion at much the same time, arguing that a blind man given sight could not even tell up or down through optical means alone. William Cheselden also acknowledged this idea, as a physiological occurrence, after curing cataracts in a boy of 14: ‘He knew not the shape of anything, nor any one thing from another, however different in shape of magnitude’, having only considered the ‘objects’ as ‘partly-coloured planes, or surfaces diversified with paint; but even then he was no less supriz’d expecting the pictures would feel like the things they represent … and asked which was the lying sense, feeling, or seeing?’28

In early modernity, therefore, vision was crucially being aligned to what was actually experienced. Locke argued conceptual knowledge was not axiomatic: it was neither ‘God given’ nor deducible by mathematics and logic. Yet just as continental rationalism’s roots derived from the philosophies of Pythagoras and Plato, so it constructed Western relations between pseudo-axiomatic systems of perception and knowledge within a particular mathematical model of space and time. The work of Pythagoras and Euclid developed through Western culture as ‘classical’ models of geometric, spatial ordering. From Abraham Bosse’s configuration of the body in space (Fig. 6) in the Renaissance, to Muybridge’s photography, to contemporary computer virtual motion capture, these are all predicated upon a hypothetical model of time and space that derives from the technological realisation of the spatio-temporal linearity of classical space. Challenges to this order continue to remain peripheral to this dominant configuration of visual encoding.

As Cubism drew attention to the process of painting, it questioned existing, culturally embedded representational practices of ordering space and time. Whilst a history of Western visual coding is too immense to be considered here, some consideration must be given in order to understand Cubism’s radical proposition. A few examples and a brief look at perspective demonstrate the notion of a picture as an ideologically encoded surface. Jesse Prinz writes:

Pictures play an integral role in the way we communicate, the way we learn, and, more generally, in the way we represent the world. Indeed, most cultures make wide use of pictures, inculcating their young with a preferred mode of pictorial representation.29

A child must be taught how to think and represent in order to participate within its culture. One acquires the ability to participate in culture by learning and enacting its codes, regardless of their ‘truth’. Likewise, referring to non-Western cultures: ‘Some anthropologists observed that pictorially innocent people cannot interpret pictures at all (prior to some kind of training)’,30 Prinz notes that the Me’en tribe in Ethiopia, when shown two pictures of familiar animals, recognised these representations, ‘but that identifications never came immediately. They usually recognized particular elements of an image (a tail, a foot, horns, etc.) before piecing together the whole.’31 When shown something more complex, such as a hunting scene with pictorial depth, the Me’en, in common with other ‘pictorially innocent’ subjects, could not interpret the image.32 Western representation is not an inherent truth, but a regime of pictorial codes. Indeed, it has no axiomatic status, for indeed, to refer to the Kantian notion, no representation can ever adequately portray the totality of the existence of the ‘thing-in-itself’. It can only be spoken through language as a phenomenon.33 Prinz tells the story of another tribe: when presented with a picture of a horse, they could not understand what it represented. However, they made the link when the referent, a real horse, was brought to them. Sense was made through a cognitive relation between the horse and the representation, by decoding the image. This was also the beginning of the tribe’s inculcation into the Western pictorial tradition. Even recently, perspectival pictures of birds – therefore not simultaneously displaying all their limbs – disturbed Australian aborigines, who interpreted them as mutilated.34 Anthropology suggests that culture configures knowledge and inscribes representation – it is neither inherent nor intuitive.

In Art and Illusion Ernst Gombrich explored the production of visual codes by initially referring to the West’s inability to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. He suggested that the Egyptians actually ‘shunned’ the use of three-dimensional representation ‘because recession and foreshortening would have introduced a subjective element’.35 Likewise, Erwin Panofsky in Perspective as Symbolic Form claimed the ‘ancients’: ‘more or less completely rejected perspective, for it seemed to introduce an individualistic and accidental factor into an extra- or supersubjective world’.36 Perspective inherently configures space for a privileged subjectivity by providing a point from which the world is issued. The Egyptians produced ‘pictograms’ for differently privileged subjects, which proved intractable to Western modes of interpretation. For example, the dead are represented among the living without apparent difference. Such content belongs to a drastically different belief in existence and knowledge, and therefore representation. Also, what we know of Egyptian ideas about time suggests they greatly differed from Western models with teleological principles. Instead, time eternally recurs. Egyptian coding is too conceptually different for a Western subject, whose codes have been constructed around linear space and time, to understand. The Egyptian picture becomes a ‘cryptogram’ – an object of knowledge for decipherment. Gombrich repeats the term ‘cryptogram’ throughout, concluding: ‘The coding process of which Sir Winston Churchill speaks begins while en route between the retina and our conscious mind.’37 Whilst Gombrich’s explanation is simplified (for example, cognitive ‘pre-conception’ and early and late levels of object recognition in cognitive process occur), the idea persists of representation as crypto-gram – or the encoded drawing of the hidden (kryptos-gramma). A significant part of a subject’s cognitive processing is culturally produced, and Gombrich concludes, ‘primitive tribes that have never seen such images are not necessarily able to read them’.38 In a typically post-Kantian statement he writes: ‘There is no neutral naturalism. The artist, no less than the writer, needs a vocabulary before he can embark on a “copy” of reality.’39 The West understands the representations of other cultures as cryptograms whilst reciprocally the Me’en tribe, for example, attempt to decode the West’s kryptos through its gramma.

According to Gombrich, Western art has derived from ‘Greek art of the classical period concentrated in the image of man almost to the exclusion of other motifs’.40 Anthropocentric content occurred as the Greeks ‘developed the cryptograms for the rounded form as distinct from the silhouette, that is, the three-tone code for “modelling” in light and shade which remained basic to all later developments in Western art’.41 Together with mathematics – and specifically geometry as a technology of configuring bodies in space – Greek philosophies constitute a set of visual codes that are intrinsic to the Western episteme. With specific reference to the Renaissance, Martin Kemp surveys this trajectory of mathematical integration of vision and knowledge within representation. Inherited from parts of Greek writings, linear perspective ‘was invented in the form we know it, during the early part of the fifteenth-century in Florence’.42 Kemp is referring to the Renaissance engagement with, and popularisation of, fragments of Greek and Latin works, particularly those concerned with geometry. Renaissance theorists were ‘engaged in the search for the “true” Euclid, in order to understand and amplify his exact science’.43 Subsequently, a system of drawing developed by the Florentine elite from ancient Greek fragments permeated Western culture. For some Renaissance intellectuals, representation was less concerned with pure mathematics than it was a means to develop their own Platonic ideologies and to discover the essence of elements, pure forms and solids. For others, linear perspective served as a convenient language to promote religious beliefs.

Kemp proposes that ‘[f]or almost four hundred years from 1500 it [perspective] served as the standard technique for any painter who wished to create a systematic illusion of receding forms behind the flat surface of a panel, canvas, wall or ceiling’.44 Perspective as a ‘standard technique’ has now endured for more than 500 years, and survived its limitation to plastic representation. The dissemination of perspectival vision-machines continues to reproduce its tradition with every photograph. For Jean-François Lyotard, the camera is an industrialised, even cybernetic, embodiment of perspective within culture, but crucially it cannot reconstitute the experiential continuity of the body. This production of vision can be linked with his notion of disembodied intelligence, producing a genderless, inhuman episteme that fractures the inseparability of body and thought: ‘a poor binarized ghost of what it was beforehand.’45 The perspectival configuration of time and space is simultaneously pictorial and conceptual, and the camera is perhaps today the most ubiquitous, accessible and ‘democratic’ of mediums. As an ‘invented’ system, mathematical geometry informs the Western construction and organisation of knowledge. Yet despite the striving for a ‘mirror of nature’, as Kant writes, ‘our representation of things, as they are given, does not conform to these things as they are in themselves, but … these objects as appearance conform to our mode of representation’.46

The establishment of geometry, as a form of representation, therefore configures the code upon which a subject has an imagined relation to an exterior time-space. In the Origin of Geometry, Husserl examined how geometry, symbolic of ‘all disciplines that deal with shapes existing mathematically in pure space-time’,47 came to constitute culture. He understood it as hypothetical concept, an invention embedded to order knowledge, although contrary to conscious ‘psychic existence’.48 (Although cognitive existence at a cultural level of visual decoding in turn supplements the notion of what a ‘psychic’ existence is, though Husserl’s point remains, geometry is not innate.) Its success, as Husserl sees it, lies in its condition as a ‘supertemporal’49 language; it remains outside of time whilst ordering it. For example, the linearity of time and space is both concept (episteme) and system (ontology). This condition allows it to become an ‘“ideal” objectivity’.50

Husserl’s enquiry takes a Kantian approach. Kant had himself been influenced by English empiricism in Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (1786). In the former, Kant concluded that human knowledge could only know phenomena of its own sensations; it cannot know ‘things’, noumena, outside of language’s internal rhetoric. What is understandable – something that Foucault argues is reflective of the post-Renaissance classical era – are empirical conclusions. An a priori condition may be concluded from a posteriori research. In Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, Kant argued that a priori concepts can relate to empirical information, but that human conceptual understanding transforms the noumenon, in a process characterised by concepts of force and energy, of ‘ether’. Anticipating Husserl, Kant believed the argument for the axiomatic position afforded to mathematics to be problematic, insofar as mathematics, whilst an incredibly useful system, fundamentally distorts the noumena. He complained that mathematics ‘only bases its cognition on the construction of conceptions, by means of the presentation of the object in an à priori [sic] intuition’.51 Whilst philosophy and metaphysics are concerned with epistemic frameworks on which to base reason, mathematics is constructed upon prior metaphysical assumptions. (This is why Husserl questioned its axiomatic status.) It functions according to its internal rhetoric: it is a construction within a construction. Science, for Kant – as with geometry for Husserl – was premised upon an abstracted, metaphysical assumption. Consequently, ‘there may be as many natural sciences as there are specifically different things (for each must contain the inner principle special to the determinations pertaining to its existence)’.52 As no singular truth of reality exists, partial truths may build a body of knowledge. Nietzsche later used this idea in his philosophy of perspectivism, commenting: ‘There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective “knowing”; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more complete will be our “concept” of this thing, our “objectivity”.’53 By accommodating an infinite number of approaches, the thing-in-itself can be more fully considered. Again, Kant anticipated later thinkers such as Bergson, William James and Husserl:

mathematics is inapplicable to the phenomena of the internal sense and its laws, unless we consider merely the law of permanence in the flow of its internal changes; but this would be an extension of cognition, bearing much the same relation to that procured by mathematics of corporal knowledge, as the doctrine of the properties of the straight line does do the whole of geometry; for the pure internal intuition in which psychical phenomena are constructed is time … the observation itself, alters and distorts the state of the object observed. It can never therefore be anything more than an historical … internal sense.54

For Kant, mathematics is profoundly limited in articulating change. Instead it distorts ephemeral and unstable phenomena into objects of permanence. He proposed that the metaphysical foundation for natural science should instead be based upon ‘Phoronomy’ (motion and kinetics), Dynamics (the ‘quality’ of matter as force), Mechanics (the relation between motion) and Phenomenology (the phenomena of the senses). The investigation of these fields would constitute a foundation of science, harmonising the relationship of energy with subjective phenomena. This was a radical departure from existing regimes of knowledge and mathematical expression.

Writing after modernity’s challenge to classical systems of thought and (perspectival) representation, Husserl’s philosophical problem therefore was how geometry became an ‘ideal object’ when it was ‘anything but a real psychic object’.55 Its first appearance could not have been objective existence, yet it came to attain that position in culture. Firstly, its possibility as a language provides self-evidence. Secondly, as language, it can be accessed through time and space (such as the example of Renaissance perspective drawn from Greek texts). Thus, Husserl writes, ‘what perhaps emerges with greater and greater clarity there belongs the possible activity of a recollection in which the past experiencing [Erleben] is lived through in a quasi-new and quasi-active way’.56 As a ‘supertemporal’ language, its framework reconfigures the past and structures the future through linear, and teleological, claims on time in a way that ‘can be actively understood by others’.57 Consequently, it becomes ‘self-evident’,58 disseminated throughout culture as ‘identically repeatable’.59 On this condition Husserl argues that ‘there is a passive taking-over of ontic validity’60 as geometry becomes axiomatic and separated from the contextual meaning of its historical invention. Husserl observed how, within modernity, geometry was a ‘ready-made concept’ within textbooks.61 Human knowledge therefore consisted of applying an internal structure of the language rather than perceiving the necessity and use of the structure in ‘overlook[ing] the genuine problem, the internal-historical problem, the epistemological problem’.62 Therefore the reduction of representation to linear perspective, what Panofsky termed as ‘a rational and repeatable procedure’,63 conforms precisely to Husserl’s model. Perspective is a communicable, ‘supra-temporal’ language, though one that fails to express its own historical and epistemological problems. For example, Damisch’s study of Piero della Francesca reveals his system ‘holds for countless perspectival sketches and studies: each is reducible to a principle of construction that can vary within certain parameters but that nonetheless conforms to a single design principle’.64

Perspective, as a mechanism of projection conceived over five hundred years prior to Husserl, continued to dominate cultural representation within modernity. After its Florentine reconstruction from Ancient Greek fragments, perspective achieved axiomatic status throughout Europe, its ‘transparency’ embedded in painting’s appeal to naturalism and veracity. We may usefully link Husserl’s concern here with Foucault’s later attention to the supposed transparency of the signifier’s relation with the signified in Renaissance art. Foucault elucidated some of Husserl’s problems, referring to language in the Husserlian sense as having ‘laws of a certain code of knowledge’,65 observing that order ‘is given in things as their inner law, the hidden network that determines the way they confront one another, and also that which has no existence except in the grid created by a glance, an examination, a language’.66 Whilst Husserl warned of perpetuating a certain regime of time and space, Foucault realised these are ‘the fundamental codes of a culture’67 governing subjectivity and experience, through the ‘already “encoded” eye’.68

In The Order of Things (1966), Foucault discussed the cultural development of language since the sixteenth-century in terms of historical modes of existence. To put Foucault’s thesis simply, three epistemic shifts in Western history arose from the transformation of the relation between language and experience. The Renaissance was characterised by a transparent relation between the signifier and signified, whilst the Classical period (from the mid seventeenth-century) observed the conceptual difference between them. Lastly, the Modern, beginning in the 1800s, critiqued the relation of the signifier to the signified and consequent claims of knowledge through the relationship between form and content. During the Renaissance, the transparency of the sign in perspective was understood as the faithful reconciliation of the human with a divine ordering. According to Foucault the signifier and signified were united here through ‘resemblance’, before God’s dethronement in increasingly secular Classical and Modern periods. Foucault argued that Renaissance models of knowledge understood the universe as ‘folded in on itself’.69 He states that ‘[p]ainting imitated space. And representation – whether in the service of pleasure or of knowledge – was posited as a form of repetition: the theatre of life or the mirror of nature, that was the claim made by all language.’70 Representation conceived as a ‘mirror of nature’ is particularly important here, as geometry became a ‘Divine’ architecture for structuring the world through perspective. Indeed, the term ‘mirror of nature’ is conflated with the commonly recognised ‘inventor’ of perspective, Filippo Brunelleschi. His experiments exemplify Foucault’s notion of language and the world as ‘a uniform and unbroken entity in which things could be reflected one by one, as in a mirror, and so express their particular truths … language is not an arbitrary system; it has been set down in the world and forms a part of it’.71

Brunelleschi’s tavoletta, a proto-photographic device, was described by Antonio Manetti as ‘seeing truth itself’.72 For Damisch, Brunelleschi’s demonstration ‘implies a process of duplication, of repetition, of doubling whose agent is the mirror’.73 Damisch draws upon the same notions as Foucault and Husserl (synthesising the positions articulated in the former’s use of ‘similitude’ and the latter’s ‘ideality’) in his own statement regarding perspective: ‘The first experiment already appealed to a properly geometric idea of similitude, itself based upon a work of idealization.’74 Accordingly, Alberti’s On Painting (1435) – one of the fundamental texts of Western visual culture – ‘is an entirely mathematical book’,75 part of a mode of idealising ‘pure limit-shapes’,76 that sought to codify reality. The ‘truth’ of representation is simultaneously geometric and idealised, a divine ‘mirror of nature’.

Geometry accounts for the apparently transparent relationship between the observer and the painting. The subject is positioned at a specific point within a perspective ‘governed by a system of rectangular Cartesian coordinates distributed across three axes’.77 The surface and subject are calculated within a ‘visual pyramid’ emanating from the static eye (Fig. 7). Here, one’s point of view is precisely constructed at the geometric intersection of subject and canvas. The vanishing point corresponds to ‘the centric ray’, emanating from the eye to ‘“pierce” the real object’.78 Within painting, the position of the spectator, reduced to a disembodied optic, is assigned a precise site. As we shall see, such a conception of the eye is anathematic to the modernism of both Gleizes and Delaunay, albeit in very different ways. Nevertheless, the eye conceiving of space defined by Euclidean laws consisting of planes, intersections and triangles is perpetuated throughout Western classical discourse. This is the classical cultural production of the relation between body, time and space.

The production of coded representation and the disembodied subject is a prior condition of Renaissance epistemology that is necessary for ‘similitude’. Yet this ‘reality’ is premised upon inhibited vision, manipulated into a single, static viewpoint for which the illusion of reality is created. Damisch’s notion of the perspectival ‘mirror stage’ occurs as the subject is forced into a viewing position whereby the reflection is the mirror of reality, like Foucault’s notion of the transparent resemblance between signs. For Brunelleschi’s tavoletta, I suggest this depends on a prior vacuity, the hole, into which the subject is inserted to complete the punctured surface through its intercalation within the viewing position. The subject is aware that it completes the apparatus of vision through its participation. However, the transparency of the ‘mirror’ of reality provides a point that betrays its illusion as the subject observes itself in the process of looking. Therefore whilst Manetti exclaimed he was looking at ‘truth itself’, the illusion contains an implicit critique of itself through its puncture: this is the simultaneous invisibility and intercalation of the subject, its conscious act of looking, and the force by which the system demands subjection to its perceptual regime. Indeed, whilst perspective is normally seen as privileging the epistemic superiority of the viewer, on the contrary, it envelops the subject in the established process of viewing. The viewer is subject to the physical positioning and illusory configuration, its intercalation in the vision-machine means it is ‘elided as subject of the geometral plane’.79 (This is in contrast to Cubism’s later incorporation of both subjective presence and viewing process.) This example is consistent with Foucault’s belief that ‘man’ as a subject did not exist before the eighteenth-century, as no place is assigned the subject other than an immobile viewing position. As we shall consider, the human subject in the nineteenth-century – as a new site of knowledge – began to overturn this optical stasis. Given that the mobility of vision is crucial to Cubism, this certainly suggests a radical shift away from the (im)mobility of the eye required by the Renaissance’s encoding of the static visual field and order of knowledge.

The incorporation of the immobile eye within the perspectival vision-machine is crucial to Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Betrothal (1434). Like Brunelleschi’s tavoletta, there is a mirror at the vanishing point, but it reflects not the observer as captive spectator, but two men, one of whom may well be the artist. As with Brunelleschi’s invention, the painting elides the subject by enforcing their shared position with the artist, who is not in the process of painting, but witness in the focal point of the mirror. Whilst Damisch suggests that the viewer must take up a voyeuristic position because no view accommodates them, the viewer is nevertheless able to assume someone else’s point of view. Western pictorial construction has depended on the fantasy of vision from the site of another, a conflation of viewer and author. And, as Brunelleschi’s experiment inadvertently demonstrates, in its revelation of the point from which the subject is looking, the subject may indeed find itself as ‘other’ in the process of observing, but also as the creator of meaning. Whilst not necessarily satisfying Foucault’s model of uncritical observation in the Renaissance, it remains true that initially the tavoletta was constructed as a literal rendering of pictorial surface as ‘mirror of nature’, whereby one was supposed unable to tell whether one was observing the real thing or its simulacrum. It obeys Husserl’s model of procedural reification as both self-evident and repeatable. The subject of painting is simultaneously the object of knowledge, in which culture is mathematically configured, and therefore, to quote Damisch, anticipates a ‘positivist’ philosophical position ‘prepared to ignore the role of the subject in instituting a truth’.80 The world can be constructed, measured and observed through an objective procedure independent of the human subject.81

Perspective is therefore not ‘natural’ but a cultural construct with its own history. Its form may have evolved mathematically, but it also belongs to specific sets of cultural beliefs at particular historical moments. Neither its ‘invention’ nor its subsequent popularity and dissemination occurred in isolation. As Damisch claims, people ‘learn to see an image in perspective, instead of seeing’.82 Perspective was disseminated under the auspices of religious institutions, exporting an ideology premised on divinity to other cultures. Linear perspective became the visual realisation of the divinity of mathematics, its ‘perfection’ as a language mirroring the ‘perfection’ of God. This reflection corresponds with Foucault’s idea of representation as the literal reproduction, or resemblance, of ‘the invisible form of that which, from the depths of the world, made things visible’.83 For Kemp, such representation proposed ‘all figures in the whole universe can be drawn together’.84 Masaccio’s Trinity (c.1425–6) obeys the emergent spatial architecture of Brunelleschi’s model in its representation of the divine. The connection between the two subsequently became convention. Throughout the Italian Renaissance, perspectival composition for religious institution was concerned with centrality and the convergence of lines to a single point, namely the point of truth: God. The mathematical harmony of space and time was equated with a universal theological order, embedding spatial geometry within religious belief whilst eliding subjectivity and time. (Even an empiricist like Berkeley argued the ‘other’ was created by God and was therefore a stable principle from which to derive knowledge.) Late-Medieval and Renaissance Italy found in perspective a mirror for the laws of a divine universe and a truth of space. As such, there is a direct relation between God, the cosmos and human language. Foucault termed this ‘a non-distinction between what is seen and what is read, between observation and relation, which results in the constitution of a single, unbroken surface in which observation and language intersect to infinity’.85 Despite today’s desanctification of perspective in the proliferation of optical technology, the ideology of its inception remains as omnipotent, universal and objective.

Yet the model of space emerged from a set of cultural conditions that formed the basis of Western visuality. As Kemp notes, the phenomenon which was to become ‘classical space’ was not inevitable, but possible because of the context of Florentine culture, in particular the practical use of mathematics in a mercantile society, with revived fragments of Greek and Roman science, and an impulse for rational, humanist laws. Therefore, ‘Brunelleschi’s measured representation … was deeply locked into the system of political, religious and intellectual values’.86 Linear perspective became popular because of receptive conditions at a specific historical moment rather than any inherent axiomatic properties. Political, religious and intellectual values were therefore crucial to perspective’s emergence and dominance. The attribution of perspective to Brunelleschi even originates, perhaps, in a desire by writers such as Vasari to construct its history. (For example, Giotto had conceived of three-dimensional space and form in the fourteenth-century, whilst Gombrich and Kemp both point to its conceptual origins in Ancient Greece’s ‘mirror’ or ‘imitiation’ of nature.)87 Damisch writes: ‘Such was the prototype of perspective to which is attached, like a brand name, like a certification of pedigree, the name of Brunelleschi.’88 Perspective was not invented so much as produced from cultural conditions that allowed for the development of certain pre-existing procedures.

Brunelleschi’s work can nonetheless be understood by his production as a cultural subject. Employed as a sculptor, his preoccupation with mathematics converged into architecture, neatly synthesising the three-dimensional concerns of the three disciplines. Whilst Brunelleschi is credited for experiments on perspective, it was Alberti who fixed such an imagination of space within a documented treatise. Indeed, Kemp notes it is significant that the first written explanation of perspective comes not from a practising artist, who may have conceived of it as an artistic tool, but from a polymath, influenced by logic and classical architecture, who ‘unquestionably saw the geometric construction of space as a prerequisite for proper painting’.89 But just as Alberti formalised Brunelleschi’s experiments, so others built upon Alberti’s work as perspectival technique soon became widely practised. Kemp remarks that no artistic technique had ever been so successful, and that by 1650 every major country naturalised this system within its own culture.90 For example, Albrecht Dürer, having access to Piero’s and Leonardo’s works, and having within his notebooks a translation of Euclid’s Elements, incorporated the research and beliefs of the perspectivists into his own work. Those mathematical principles extended to conceptualising the body within space. Eventually published in 1528, Dürer’s Four Books on Human Proportion configured a geometrically rigid bodily architectonic (Fig. 8). His work, derived from extracts of Greek texts filtering through Renaissance Florence into Central Europe, marks Nuremberg’s establishment as a centre for the European Renaissance with a flourishing artistic culture specialising in the production of perspectivally derived objects within geometric space.

As geometric perspective was disseminated throughout Europe, so it became secularised, alongside culture. The divine status afforded to it and the human body declined and scientific interest increased. The story of Galileo in the seventeenth-century marks a traumatic collision between religion and science in their respective imaginations of the purpose in representing ‘bodies’ accurately. Mathematics no longer complemented theology as Galileo undermined geocentric religious ideas through the ‘divine’ language of mathematics. We see here an early rupture between two epistemic modes – new scientific reason and established religious dogma. The French adoption of linear perspective also demonstrated a shift from ‘cosmological’ concerns to a more ‘modern’ representation of spatial architecture. Architects dominated perspectival research in France, and consequently linear perspective was conceived perhaps less theologically but more practically through architectonic demonstrations and examples. Perspective, freed from theology, entered into ‘the golden age of the perspective treatise’ after 1630.91 Panofsky writes that ‘these very forms … belong to the moment when space as the image of a worldview is finally purified of all subjective admixtures … replacing for the first time the simple Euclidean “visual cone” with the universal “geometrical beam”.’92 Mathematics and physics, with the scientific revolution of the seventeenth-century, moved perspective into the more ‘practical’ domains of science, engineering and architecture, and into cultural consciousness. The notion that perspective constructed vision rather than was constructed by vision parallels Foucault’s argument that the Classical period breaks with the theological ‘mirror of nature’. Indeed, Locke and Molyneux would demonstrate this rupture through their probing of the axiomatic status of objective vision at the end of the seventeenth-century.

Foucault identified the establishment of ‘man’ as an object for knowledge once subjectivity became the internal principle of first epistemic, and then governmental, organisation.93 Representation shifted from the objectively known to the subjective (as demonstrated in J.M.W. Turner’s treatment of perspective, for example). The epistemic emphasis shifted from the overcoding of human experience by mathematical abstraction to process, the production of knowledge by the body that demanded interpretation and regulation. The Classical episteme ‘presupposes a general ordering of nature [… through] entire systems of grids which analyse the sequence of representations … and redistributing it in a permanent table’;94 this, for Foucault, was because ‘man’ as a concept did not exist until the end of the eighteenth-century.95 If the Renaissance encoded similitude, the Classical era, faced with the denigration of such an approach, constructed an encyclopaedic archive to categorise and classify knowledge. This included inserting the body within a panoptic regime, just as other cultural bodies were displayed within ‘curious’ cabinets. The modern era broke from these regimes as preoccupation with the relation of the human body to knowledge ruptured prior forms of knowledge. As Foucault observed, with modernity’s constitution of man:

knowledge has anatomo-physiological conditions, that it is formed gradually within the structures of the body … there is a nature of human knowledge that determines its forms and that can at the same time be made manifest to it in its own empirical contents.96

This epistemic shift is critical to understanding the profound challenges that nineteenth-century works presented to visual representation. Impressionist canvases therefore ‘played on a tension between an openly dabbed-on plane surface and a rendering of sense-impressions of seen objects’.97 The importance of the dynamic between process and surface is profoundly important in anticipating Cubism’s ‘challenge’ to figurative representation. An avant-garde emerged – however marginalised in comparison to the culturally embedded classical perceptual model and its mechanical reproduction in modern technologies such as photography and film – whose inspiration derived from exploring the world through subjective phenomena as the new principle of reality, and therefore, representation. The establishment of the human sciences developed a new figure to accompany their transformed episteme: a subject of embodied perception as the producer of knowledge and meaning. Following Foucault’s identification of two types of knowledge yielded from the body, Crary writes:

By the 1840s there had been both (1) the gradual transferral of the holistic study of subjective experience or mental life to an empirical and quantitative plane, and (2) the division and fragmentation of the physical subject into increasingly specific organic and mechanical systems.98

Yet despite the socio-political implications of new modes of bodily knowledge producing greater technologies of control and regulation of human subjects, the process of reimagining the human being was of profound importance scientifically, philosophically and artistically, in undermining the ‘axiomatic’ laws pertaining to an ‘external’ reality. However, as I will argue, modern ways of thinking about the subject, through its embodiment, contained forms of biopolitical control. Not only was the subject transformed into the new object of knowledge, but also the new object of power through new disciplinary techniques upon the subject through its body. (It is from this context that the ‘cubist grid’ would contain the possibility of emancipating, and controlling, the subject.)

Crary suggests that the Modern era ‘collapsed’ the Cartesian optic and the camera obscura as the model for conceptualising visual experience (Fig. 9): ‘For over two hundred years it subsisted as a philosophical metaphor, a model in the science of physical optics.’99 ‘Collapse’ is perhaps misleading, as the disembodied, geometric optic still dominates Western culture through the mass dissemination and accessibility of lens-based media. Nevertheless, in the Classical era, a critique of Cartesian optics was established, proposed by Locke, Molyneux and Berkeley, and in the 1820s and 1830s new models of the observing subject became increasingly clear. Rather than ‘collapse’, we might suggest an epistemological ‘divergence’ for these alternatives, yet it is within the nineteenth-century that Crary locates the demise of the existing configuration of the static optic, fundamentally incompatible with a regime of knowledge consisting of dynamism and flux.

Both Crary and Baxandall refer to Jean-Simeon Chardin’s paintings as typifying this shift. For Crary, Chardin’s works are ‘a last great presentation of the classical object in all its plenitude’.100 However, the difference in the thought of each is evident when Baxandall argues that Chardin’s A Lady Taking Tea (1735) distorts perspective to create an uncomfortable viewing position, suggesting the teapot is ahead of its time, as ‘rather 1910’.102 It appears overly flattened, whilst the lighting and colour scheme seem deliberately unreal. This, Baxandall suggests, implies Lockean ideas, received especially through Diderot, who wrote on both Chardin and Locke’s Letter of the Blind (1749). Baxandall also argues that proto-scientific investigations inform Chardin’s painting, and concludes that these ‘Lockean’ paintings ‘represent, in the guise of sensation, perception or complex ideas of substance, not substance itself’.103 Even though his argument is somewhat attenuated, Baxandall nevertheless draws attention to the critical importance of a development in visual science regarding knowledge concerning the human subject.104 This research undermined the notion of the disembodied, geometric optic as a universal model of comprehensive vision.

After the eighteenth-century, research became increasingly sophisticated as the shift of location in the production of reality to ‘man’ as the transformed object of knowledge signified new epistemological discourses. Clark and Jacyna observe that the first half of the nineteenth-century saw a ‘revolution’ in neuroscientific concepts that overturned ideas of Classical Antiquity105 These neuroscientific foundations were dependent upon technological, but also conceptual developments, particularly relating to the emergence of romantic philosophies, especially in Germany, that influenced biology through ideas that universal laws connected organic nature and the human, in contrast to Cartesian discourses on the ‘mechanical’ body. Clark and Jacyna argue that proto-neuroscientific research was influenced by Kantian philosophy and a Romantic emphasis on subjectivism, inspiring a proto-neuroscience through an ‘intimate association with the phenomena of the mind’.106 The Naturphilosophen of neurophysiology, according to Blustein, occupied ‘a pivotal position at the intersection of philosophy, biology, psychology, and medicine.’107 This epistemic shift nevertheless created cultural discord as the Académie des Sciences defended the traditional view that the spinal cord grew from the brain, whilst Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Christoph Spurzheim showed, as it is now believed, the brain instead develops from the spinal cord.

The emergence of visual physiology was concurrent with investigations into the ontology of light. Renaissance accounts of vision upon direct ‘rays’ still ranged from Alberti to Newton, ‘demonstrated’ by the camera obscura, emitted by the observer or entered the observer’s optic. However, the ‘science’ of ‘reality’ rapidly undermined existing beliefs about the world. The idea of the electromagnetic spectrum developed after Augustin Jean Fresnel’s demonstrations in 1821 of transverse light vibration and refraction. His theories were soon incorporated within James Clerk Maxwell’s work in electric and magnetic fields that demonstrated that light was constituted by waves, not linear rays.108 Reality was no longer geometric and mechanical, but understood as continuous and fluid, as physics and physiology bifurcated the once unified model of vision into diverging fields of the human sciences. Not only was light itself mobile but so was sensation. For example, Johannes Müller contributed to a specifically modern episteme by chemically and electrically manipulating bodily sensations, proving perceptual experience was not purely created from a stable external ‘reality’. Crary suggests that Müller’s research was as important for the nineteenth-century as Molyneux’s was in the eighteenth, especially as it inspired Helmholtz’s Optics. Indeed, these advances anticipate Ernst Mach’s characteristically modern ideas regarding knowledge as sensation that occurs exclusively within the human subject:

In mentally separating a body from the changeable environment in which it moves, what we really do is to extricate a group of sensations on which our thoughts are fastened and which is of relatively greater stability than the others, from the stream of all our sensations … it would be much better to say that bodies or things are compendious mental symbols for groups of sensations – symbols that do not exist outside thought.109

Similarly, Henri Poincaré wrote that ‘our perception of space is the product of an internal coordination of our various sensory faculties into a spatial gestalt we mistakenly identify as external to us’.110 In relocating meaning within embodied sensation, a fundamental transformation occurred concerning notions of truth and knowledge. In many ways, scientific knowledge about human relation to the world exemplified Kant’s established philosophical position: the ‘thing-in-itself’ cannot be known, only known through representation. Human knowledge is restricted by perceptual limitations and the internal conceptual principles of knowledge regarding the object of enquiry. The demolition of an anthropocentric universal view occurs with the ‘crisis of man’ as humanity realised its limitations: modernity’s epistemic rupture profoundly severed any direct relation to the noumenon, the ‘thing-in-itself’.

Paul Cézanne’s canvases unfolded from a historical moment when, from very different fields, Ruskin and Helmholtz converged in their understanding that perception was based upon a perpetually changing chaos of coloured sensation. The former referred to vision as an ‘arrangement of patches of different colours variously shaded’,111 whilst the latter commented that ‘[e]verything our eye sees it sees as an aggregate of coloured surfaces in the visual field’.112 William James continued the empiricist approach to vision and knowledge, inaugurated by Locke and Molyneux, hypothesising that a newborn baby’s environment appears without structure, as ‘a blooming, buzzing construction’.113 Karmel also shows how Hippolyte Taine’s empirical philosophy on psychophysics and linguistics within France is of contextual importance to understanding Cubism.114 Therefore, cross-disciplinary and trans-European research understood perception as not merely the transparent translation of ‘reality’, but a complex, mediated and encoded process. Vision was a psychophysical process, reconfiguring environmental energy into optical, cognitive information. Even at early level cognitive entry, energy is believed to turn into ‘part objects’ that are later coded into coherent objects with edges, relations, patterns and colour.115 Human perception, and therefore knowledge, is now understood as premised upon a process of alienation and difference between forms within the environment’s energistic continuum. Whilst the environment consists of dynamic, interpenetrating energy, psychophysical perception misrecognises the fundamentally interconnected condition of the world.

Cézanne helped rearrange pictorial order according to sensation and energy as the principle of representation. He configured the environment according to the experience of embodied phenomena, as argued by Ruskin, Helmholtz and James. The intercalation of the Western subject into geometric perspective and objective figuration was challenged as Cézanne expressed matter as energy and flow, rather than through form, deforming objects into intensities of coloured brush-strokes in a profound meditation on the limits of perception. For example, a rock, or even a mountain, is commonly a metaphor of stability and constancy within Western spatio-temporal models of vision. However, it is still energy, vibrations in continuous transition through constant atomic migration. This is the condition of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte Victoire (Fig. 10). The rock’s inertia is constructed by spatial thinking; human perception does not perceive the rock’s fluxive state because of its own internal construction. A perceptual regime with greater emphasis on temporality could even think the rock fluid. Humans, on the other hand, organise visual information into a specifically contrived set of object coordinates that constitute its relation to space. Vision is psychophysical, even though the ‘truth’ of reality has been conflated with the veridicality of seeing. Cézanne explained to Joachim Gasquet, using his interlocking fingers:

That’s what you have to do. If I move too high or too low, it’s all wrong. Not one part must be out of true; there must be no chink through which arousal, light, truth can penetrate. I work the whole picture uniformly, you see, as a whole. I bring everything that tends to move apart into one rhythm and one conviction.116

Everything exists here as relativised relations, never fragmented into a linear schema; Cézanne’s elaboration of colour created the impression of a writhing mass of interpenetrating intensities. In the later paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, he used a technique labelled passage, whereby hitherto rigid objects within perspectival planes interpenetrate, moving beyond their supposed boundaries as they merge into each other. Cubist painters adopted the technique to appeal to a modern conception of human visuality rather than use Albertian perspective, with all that it implied for the coding of space and time. Gleizes later wrote with Metzinger:

From [Cézanne] we have learned that to alter the coloration of a body is to corrupt its structure. He prophesies that the study of primordial volume will open unknown horizons to us. His work, a homogenous mass, shifts under the glance, contracts, expands, fades or illuminates itself.117

Baxandall comments that whilst Cézanne influenced many younger painters, they all drew upon different aspects of the work.118 His paintings helped open perceptual representation as an investigation into the derivation and production of knowledge. Thus Cubism’s challenge to the embedded status of classical vision, and its encoding of the body, was also an attack on the observer since it undermined culturally inculcated visual process of organisation and knowledge. Indeed, Gleizes believed the anger directed towards his work was a consequence of refiguring the sitter – the ‘anecdotal subject’ – as a set of interlocking planes. Whilst this challenge had begun in the nineteenth-century, cubism crucially provided a quasi-coherent force through its radicalising of pictorial form through everyday objects. The modernists of ‘1910’ do not institute a sudden rupture; they are, rather, part of a historical unfolding. Nor is the significance of modern thought evenly disseminated (we do not live in a non-Euclidean culture, even if non-Euclidean mathematics has long been established). Cubism was radical because its conceptualisation of an epistemological rupture was made in a visually and publically accessible form.

Gleizes exhibited La Femme aux Phlox (Fig. 11) at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911. Daniel Robbins suggests it was the Salon, rather than the more hermetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque, that effectively launched ‘Cubism’ as a public and international movement, making the five artists famous overnight.119 Robbins supports Gleizes’s claim that the Salon’s impact reverberated throughout Europe, and quotes his remark:

Painting which until then had been touched only by a small number of amateurs, passed into the public domain, and each and everyone wanted to be informed, let into the secret of these paintings which represented – it seemed – nothing at all. It was necessary to press, as in a rebus, what they signified.120

The Salon was divided between the established Neo-Impressionists who occupied a central position, whilst Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Léger, Robert Delaunay, Metzinger and Marie Laurencin were marginalised in Room 41. The success and scandal provoked by the Cubists was in part due to their self-promotion, fuelled by a belief in their social importance and cultural significance. Closely aligned to literary figures such as Apollinaire, André Salmon and Roger Allard, the painters believed – after the Salon d’Automne of October 1910 – that they needed to be shown as a group. It was here they first recognised a convergence in styles. Gleizes had already been acquainted with Metzinger and Delaunay, but had apparently not realised the importance of their works for his, despite their having been hung nearby. The painters formed a small group, joined by Apollinaire, at the Closerie des Lilas. At these meetings they decided their individual work needed to be promoted collectively to enhance the impact of their work.

By hijacking the Salon’s AGM weeks before the opening, the painters replaced unsympathetic Salon members with more open-minded, progressive figures. (Metzinger’s application was so successful that it ironically received 500 votes out of a possible 350.) Le Fauconnier was chosen as President and he, Gleizes, Léger, Delaunay and Metzinger chose ‘Salle 41’ to show their work. On opening day, perhaps because of the painters’ increased profile, the crowds around Room 41 made entry difficult. Golding writes that ‘a violent storm of criticism and derision was let loose in the press’,121 whilst Peter Brooke notes that ‘[t]he painters had hoped to make an impact by being exhibited together, but they were not prepared for a riot … culminating in a raging battle in the room itself’.122 Gleizes referred to the ‘“involuntary scandal” out of which Cubism really emerged and spread in Paris, in France and through the world’.123 He proposes that

Room 41 of the Salon des Indépendants was a revelation for everyone … It was from that moment on that the word Cubism began to be widely used. Never had a crowd been seen thrown into such a turmoil by works of the spirit [appearing] as a threat to an order that everyone thought had been established forever.124

It seems surprising that such ‘turmoil’ was largely generated by one work: Le Fauconnier’s L’Abondance of 1910. The painting does not appear pictorially radical, despite its monumental size. Thematically, it was perhaps even conservatively Bergsonian in its rural nostalgia and ‘organic’ depiction of the female body. It maintained perspective, and hardly seems cubist in its superficial Neo-Impressionism. However, this ‘accessibility’ of style and content may also account for its success. It was influential for those salon cubists, such as Gleizes, whose own work developed rapidly after seeing it. David Cottington suggests the painting was ‘perhaps the best-known cubist picture in Europe before 1914’125 and Le Fauconnier was generally, if briefly, regarded as the principal innovator behind Cubism. Offering subjective representation as the internal criteria for portraiture, Le Fauconnier’s Portrait de P.J. Jouve (1909) had already made a ‘profound impression’126 on Gleizes. L’Abondance influenced a wider circle: Metzinger, the Delaunays and Léger, and the writers Merchand, Allard, Apollinaire and Salmon all visited Le Fauconnier’s studio during its painting. It derived from a proto-cubist literary background, especially that of the earlier Abbaye de Créteil commune, which had been concerned with collectivity and preserving the relations of ‘man’ and environment against technological and economic modernity.

Gleizes was deeply influenced by Léger, whose La Couseuse (1909) informed his La Femme aux Phlox, whilst Portrait de Jacques Nayral (Fig. 15) reflected the planar synthesis of body and space within Léger’s Nues dans la forêt (Fig. 12). The synthetic reconciliation of environment and figure was fundamental to Gleizes’s work. It had already been demonstrated in Léger’s painting, which Metzinger observed was ‘a living body whose trees and figures are the organs’.127 Gleizes commented of the painting that ‘the volumes were treated according to the process of progressively diminishing zones employed in architecture or mechanical models’.128 Indeed, Le Fauconnier and Léger had a mutual influence on each other, as well as on Gleizes.129 Léger had participated in the Abbaye de Créteil commune, as had Gleizes, though he was concerned with Cézannian visual strategies ‘disarticulating the figures and landscape’130 rather than having an interest in their more literary discussions. Following Cézanne, Léger’s painting interconnected form through the reorganisation of matter. Suffused by a green hue across the canvas, the classical pictorial convention of composing discrete objects within three-dimensional space from a static viewpoint was decomposed into angled planes, interlocking bodies with space.

Léger took Cézanne literally, fragmenting the world into component parts of the cylinder, sphere and cone.131 This became the compositional basis for rejecting perspectival codes, as Léger premised his painting on the importance of sensation. His work followed the ideas of Ruskin, James and Cézanne.132 In this way the world is constructed through pre-established cognitive structures with memory. As mentioned, Cheselden’s cataracts patient had no prior conception of object formation and therefore, without the principles of organisation, could only see ‘partly coloured planes’. Virginia Spate writes that for Léger, ‘changes in contemporary life had so transformed perception that reality lay in sensation rather than in comprehension of specific objects’.133 Metzinger gives an insight into Léger’s synthesis of human and environmental bodies, recoded into interconnected matter, reflecting the world composed of energy within his desire ‘to dislocate the body.’134

Léger’s work therefore existed within, and helped constitute, Cubism’s response to the transformation of culture. Following Cézanne, Léger expressed energistic flows, interfaces and multiple connections since perception no longer was bound to the optical-epistemological mirror of a hypothesised external reality. He subverted pictorial convention by applying Cézanne’s model of geometric shapes in the construction of a world consisting of matter, whereby sensation is privileged at the expense of the anthropocentric organisation of rigid objects in Euclidean space. Similarly, Gleizes’s La Femme aux Phlox undermined existing pictorial encoding through reconstructing form according to temporal rhythm. (In fact, Gleizes later wrote regarding painting: ‘all the parts are connected by a rhythmic convention’.)135 Object boundaries are displaced, and are deliberately obfuscated in drawing attention to the process of seeing. As with Léger’s painting, Gleizes’s planar technique provoked a different visually cognitive response. Like Helmholtz’s ‘surfaces in the visual field’, objects are parsed and partitioned into regions of matter rather than alienated objects in space. The viewer’s pre-established cognitive model for compositional decoding, to parse the surface before recombining those parts into the geometric whole, is frustrated by the disruption of classical techniques for representing bodies in space. And they anticipate the principles of camouflage developed in World War I that Picasso famously commented were derived from Cubism. Recognition is possible, but form is no longer the instantaneous and static condition it had become through photography as a perspectival vision-machine.

Gleizes’s painting belongs to a reflexive turn on vision, and therefore on the processes of knowledge and experience. Disrupting the spectator’s visual expectations means an increase in time spent interpreting the scene. Gleizes employed a compositional rhythm, which manipulated the spectator’s visual processes in attempting to distinguish figure from environment by leading the eye in a circular motion following the upper arm, down through the body, along the figure’s right arm and up through the lines towards the originating arm. This circularity is supported by the use of colour, texture and luminosity – properties that are vital to immediate object recognition – which obscures the discrete relations between objects and space. Indeed, the relatively uniform application of colour and light intercalates the figure with the space it occupies. Gleizes would have seen this subversion of figure-ground relations used by Cézanne and Léger. However, perhaps it was most famously employed in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907). Here body and space were refigured into planes whilst single point perspective was rejected for a process of figural rotation and condensation of perspective upon a facet. As single-point perspective confines the observer to a rational position within mathematical laws, Picasso’s painting represented a palimpsest of spaces condensed upon a single plane rather than using that plane to figure depth relations. Whilst anticipating cubist works that erase traditional object-space relationships, his striking use of colour here nevertheless maintains spatial distinction between figures. Later works such as Femme nue assise (1909–10) were almost monochromatic, facilitating the body’s fading into space. Gleizes and Léger, among others, would suspend dominant regimes of spatial representation and figural visibility through their nearly monochromatic canvases. Yet Gleizes had never seen Picasso’s work, and according to Apollinaire and others, did not meet him until after 1911 (Apollinaire was eager to connect the two cubist groups, whilst Kahnweiler was not). However, Gleizes was no doubt aware of Picasso’s canvases through Metzinger, Léger and Delaunay. Whilst ‘Cubism’ became a term for a heterogeneous mix of painters and styles, there was a shared concern with rethinking the compositional structure of painting since an external objective ‘reality’ no longer existed, whilst change and process were now understood as fundamental to perception. This shared aesthetic is precisely what Gleizes felt was being attacked in his work in 1911. Cubism reflected a crisis concerning the loss of the subject. Picasso’s subject in Les Demoiselles was profoundly re-imagined, and used by Lefebvre to illustrate his statement regarding the radical transformation of space in the early twentieth-century, whilst Gleizes’s camouflaged subject dissolves into space, in a manner akin to Femme nue assise. Brooke reports that even Gleizes’s friends found the painting hard to understand: ‘The visual convention that had baffled them was the apparent disappearance of the subject in its surroundings.’136

Although there is a perpetually unfolding relation between the individual and environment, a high proportion of perceptual attention is given to differentiating figure and environment. Before La Femme aux Phlox Gleizes’s paintings had maintained this traditional distinction between figure and world, for example in his earlier portraits of Robert Gleizes and René Arcos.137 However, La Femme aux Phlox overcame these limitations through mobilising the eye through the canvas, a technique important in Gleizes’s career. In an unpublished notebook,138 Gleizes discussed the cubist technique of perceptual flânerie throughout the canvas, and his intercalation of form achieves precisely that effect as the spectator’s visual expectation is subverted.

Edgar Rubin’s pioneering research on the ‘phenomenological analysis’ of the visual experience of figure and space was contemporary with Gleizes’s painting.139 Rubin concluded that a figure is consistently perceived in front of space, but never within or part of it. He noted that the two-dimensional distinction of figure from space occurs if one region is completely surrounded by another, whereby ‘space’ encloses ‘figure’. Although human perception has developed according to object recognition, the imposition of a cognitive framework upon the ‘chaos’ of sensation causes the misrecognition of complex or ambiguous optical information. Rubin developed the ‘Rubin Vase’ around 1915, though earlier examples of ‘multi-stable perception’, such as Louis Albert Necker’s ‘Necker Cube’ of 1832 and the 1899 duck/rabbit by Joseph Jastrow, demonstrate the impossibility of simultaneous perception of bodies in perspectival space. However, whilst these depend on the singular viewing point of perspective, Cubism would also challenge the ‘impossibility’ of simultaneous perception by multiplying the spectator’s perspectival point of view to the object projected upon the canvas. Whilst Gleizes’s painting remains concerned with volume rather than the multiple perspectives, Léger and Metzinger were developing under the influence of Picasso’s and Braque’s work. More specifically in Léger’s and Gleizes’s painting, the ambiguity of interlocking bodies, with techniques of planar rotation condensing spaces upon a plane, provided multiple visual interpretations of matter before the spectator’s reconciliation of objective forms.