CHAPTER 3

FINDING A PLACE IN THE WORLD

The hearing aids I had helped me to hear sounds and to be aware of what was around me, but they didn’t help me to understand words. I hated the first set because it looked like I had a bra — those old hearing aids were the size of a cigarette pack and they had to sit in the ‘bra’, which was a harness my mother made to hold them and which fitted across my chest. It made me feel very self-conscious.

Ingrid always made sure Richard was looking directly at her when she was speaking so he could read her lips.

I hated them because they were visible and made me look different to other people. I wanted to be like other people. They were bulky and the sound ran through a wire to an earpiece — it looked like I had a Walkman before anyone had heard of a Walkman.

It was only when I was 11 or 12 that I got the first behind-the-ear hearing aids and the freedom of not wearing that harness was amazing. I was finally able to burn the bra!

While Ingrid built the base for Richard’s lip-reading skills with her tireless and focused lessons, others played a vital role in helping her profoundly deaf child not only to communicate but to understand.

Richard had weekly sessions with a speech therapist, Chris Justin, at George Street Normal School. With her, he worked on his pronunciation and the subtleties of inflection and emphasis. She would also pick out words Richard hadn’t encountered before and ask him to pronounce them straight off the bat. On problematic words, Chris placed Richard’s hand to her throat while she spoke the word, so Richard could feel the vibration in the vocal cords and try to replicate the feeling in his own larynx. Richard struggled with the sensitivity of touch to pick up the small variations in the vocal cord vibration.

Later, Chris moved to an office on Hanover Street and with that came a technological step that allowed Richard to make a quantum leap. There she had an oscilloscope, described by Richard as having a screen about the size of a large smartphone and resembling a radar. When Chris spoke a word, a pattern reflecting the sound waves came up on the screen and Richard tried to replicate the pattern.

‘It was such a vast improvement over the “hands on the throat” technique. I really took that technology on board and I felt this was a huge step forward for me in improving my speech. I still had my days — if I got too tired — when my speech would deteriorate, but I became more aware of and conscious of how I spoke. This was important for me to interact with the normal spoken world.’

John Caselberg also became an invaluable mentor. Having moved from Nelson to Dunedin to study medicine, he became ensconced in the literary and artistic world. Through the fifties and sixties, he became an established poet. His wife Anna was the daughter of renowned painter Toss Woollaston and had once lived with Colin McCahon’s family.

For all his artistic merits, it was as a teacher of the deaf that Richard knew John. He became a significant influence in terms of explaining the colloquial meaning of words and phrases. For example, while Richard had learned the word ‘excuse’ as a reason for not having done his homework, Caselberg might bump into him and say: ‘Excuse me!’ thereby showing him the word’s different contextual uses.

He also taught Richard the rhythm of language, explaining to him that where the emphasis fell in a sentence could determine the meaning of the words in a social context as opposed to their literal meaning. This set Richard on a path towards becoming more eloquent with the English language and helped develop his lifelong love of innuendo and puns. It taught him ways to be witty and play with words, things most people take for granted because they can pick up the most subtle changes in tone or inflection.

But no matter how many words Richard learned to pronounce or puns he could create, the sounds bore little resemblance to what other children knew as normal. Consonants lacked precision, vowel sounds came out squashed, and the overall effect was a flat atonality that made it difficult for others to understand Richard until they got used to listening carefully. On top of that, he struggled with pronunciation, having to take something he’d seen via lips or oscilloscope and turn it into a sound he had never heard.

I think learning about how the vowels are formed with lip movements is an important step into understanding how to lip-read, however the phonic sounds were a real challenge since without hearing it is very difficult to interpret the difference between ‘sh’ and ‘ch’. In fact, it’s close to impossible to lip-read the difference.

Over time I’ve learned to identify the difference in the context of the sentence. But it didn’t help me when my primary school mates and I had enjoyed watching Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at a special movie premiere for primary schools in Dunedin.

Knowing my speech deficiency, my mates would poke me to recall the name of the movie. I replied innocently, ‘Shitty Shitty Bang Bang’, and they’d be all laughing. I didn’t think the movie was that funny, but I agreed with them that it was a bit humorous. Dick Van Dyke was an awesome actor — for me, his character in the movie was one that I could easily lip-read and his animated action helped me even further to understand the story.

When I got home, I told Mum, ‘I saw this movie “Shitty Shitty Bang Bang” and my friends thought it was funny.’

I guess my mother understood what they really found so amusing and took pains to explain to me that I wasn’t pronouncing it correctly. It then dawned on me that my mates were taking advantage of me!

Mum started working on me to try get the right mouth formation to produce the ‘ch’ sound. It took me some time to get the hang of it.

Another time, I was travelling with the family on the Northerner express in the North Island in the early 1970s. When the train stopped at Taihape, I tried to pronounce the station name and it would come out wrong. The Māori language took me a while to grasp. Dad pointed to his tie and then to his smiley face — tie-happy — it wasn’t perfect but it was close enough!

Naturally there was a lot of frustration in trying to understand other kids my age. Not surprisingly my frustration led to some fights. Some of the taunts could be quite demeaning. Rob Smillie had just arrived into Maori Hill primary school, and it wasn’t long before he picked out that I was a little different from the rest of the children in the classroom.

When the class broke for recess, Rob would seek me out and start to taunt me by saying, ‘Deafy, deafy’. It made my blood boil, but he wouldn’t stop.

My frustration got so bad that I lashed out and punched him in the eye! Hoo boy, Rob got a real shiner and, of course, a few words from his father about treating a deaf kid that way.

Funnily enough, we became best friends — what a way to start a friendship! I got into lots of fights back then — I had a bad temper and people kept winding me up. I didn’t like being taunted. Fighting was my way of showing them that I wasn’t a weakling. I wanted to prove myself. It would be silly of me to shy away when people were being cruel to me.

Rob Smillie will never forget the day Richard Emerson punched him in the face — and he knew he deserved it.

Rob’s father Alistair was a professor of oral pathology, and the family arrived in Dunedin when Rob was eight. That was when he started at Maori Hill School and encountered a deaf boy who spoke strangely. ‘I remember seeing him in the playground, and he looked quite different to anyone else with these things sticking out of his ears. Because he was deaf and couldn’t talk very well people thought he wasn’t that smart — but as I was to learn he was very imaginative and creative.

‘I was teasing him when I first met him, calling him terrible names like “deafy” and generally giving him a hard time. He promptly smacked me in the face and gave me a black eye. I thought, “Hang on, here’s a kid with some moxie. Here’s a guy who’s prepared to stand up for himself!” I’d thought he was a quiet boy, but he had a real spirit there. I decided he was a pretty interesting bloke, and that was the start of 40-plus years of friendship.’

Other friends didn’t bat an eyelid when Richard biffed Rob; those who had been around him long enough knew he had a short fuse, one born of frustration on various levels. His hearing aids made Richard feel self-conscious or ashamed and, from time to time, they created a feedback screech or whistle that irritated both Richard and those around him. Mostly, he reacted to other children’s cruel teasing. ‘He did get teased,’ said Grant Hanan, who started at Maori Hill School at the same time as Richard and would go on to become a lifelong friend.

‘Every so often things exploded and you knew about it — he would often fly off the handle. And Richard was always quite physical. He loved bullrush for the physical contact — he was fully up for all that.’

Richard and Grant both went to Boys’ Brigade, which Hanan remembered as being run by ‘a strict ex-army guy’ who doubled as the local butcher. He ran a military-style outfit with a lot of drill. ‘With Richard, there was an element of trying to tame the beast a little bit.’

After their initial fight, Richard and Rob became inseparable friends, their lives defined by adventure, comic books, music and trouble-making. Rob also became Richard’s ‘translator’.

‘We always had to face each other to talk — he was a good lip-reader, but you had to enunciate quite clearly,’ says Rob. ‘A lot of people found it hard to understand Richard because of his atonality, so I would play the role of translator or broker with others. We never treated Richard differently and in some ways were a little harder on him.

HE COULD CONNECT BETTER WITH ADULTS BECAUSE AT LEAST ADULTS KNEW TO LOOK AT HIM WHEN THEY WERE SPEAKING. OTHER CHILDREN DIDN’T ALWAYS UNDERSTAND THAT HE COULDN’T BE PART OF THEIR CONVERSATION IF THEY WEREN’T LOOKING AT HIM.

‘You could see and share his frustration at what being deaf was like. You could understand his handicap, and then accept it, break through it and eventually take advantage of it. In the end, I didn’t even think of him as deaf.’

When he was eight, Mike Hormann’s family shifted into Dunedin from Mosgiel and he joined Richard’s class at Maori Hill School. ‘We got on quite well at school. Between Richard and George, they had quite a few train sets and that was great for other young boys. We always had some fun at Richard’s expense but I can’t recall anyone being nasty because he wasn’t that kind of guy. He got a little bit of special attention — but not in a bad way.’

Another friend reckoned Richard didn’t mind the teasing because it brought attention — something he struggled to get from most children. Other kids either didn’t understand they had to look at Richard when they spoke or they couldn’t be bothered making the effort. As a result, he felt excluded from a lot of conversations and groups.

According to his mother, ‘He was a lonesome boy in many ways. He could connect better with adults because at least adults knew to look at him when they were speaking. Other children didn’t always understand that he couldn’t be part of their conversation if they weren’t looking at him. That’s why he’s developed a habit of trying to control the conversation, so he knows what people are talking about.’

Even when people did remember to look at Richard, it didn’t guarantee they’d be understood.

I still struggle with lip-reading, especially meeting new people for the first time and trying to get a feel of the person’s way of talking, trying to recognise how people form familiar words in their own way, trying to get a hang of their ‘accent’. Some people are naturally easy to read, others can fall into the moderate and bloody hard categories.

With the ‘moderate’ people, once I have been reading them for some time I get the hang of it, but I sometimes have to ask them to repeat things to grasp the meaning of the sentence. With the ‘bloody hard’ ones I tend to nod, agreeing with whatever they are mumbling about and hoping I haven’t been asked a direct question. For that reason, I tend to steer well away from ‘bloody hard’ ones as these people, through no fault of their own, are too hard to understand. They make me feel uncomfortable, I lose my confidence and I want to walk away or talk to an ‘easy’ person.

To avoid upsetting people who have come a long way to visit the brewery, another method I use is to ask a workmate with an ‘easy face’ to be with me. When I stumble trying to understand a newcomer, the workmate will sense that I am struggling and will repeat what the person is trying to tell me. It’s like having an interpreter.

I’ve also learnt that I can politely say: ‘Excuse me, I am deaf. Could you please look at me so I can read your lips?’ They will then quite naturally change the way they talk and often I will find this much easier.

Richard and Rob devoured the English comics of the day — such as Whizzer and Chips, and Beano — and became devotees of The Adventures of Tintin. They thought Richard’s father George looked and behaved like the Tintin character Captain Haddock, with his bushy beard and fierce temper. As a result, the boys ran around shouting ‘bashi-bazouk’ and ‘billions of bilious blue blistering barnacles!’ George in turn shouted at them to ‘stop acting the giddy goat!’ — a phrase he used so often it’s burned into Smillie’s memory.

These comic books inspired Richard and Rob to create their own strip, The Snoots and The Grunts, about a space-travelling set of families. Richard, who had an eye for detail and an artist’s touch, drew the pictures while Rob wrote the dialogue.

The mischievous inspiration of Dennis the Menace meant poor Ingrid bore the brunt of their practical jokes, like the time they rigged a bucket of water over the half-open basement door and told her the cat had gone down there to be sick. Ingrid ran downstairs only to get drenched as the bucket tipped on her head.

Ingrid laughed off the pranks, but not so George. As a result, the boys’ rebellious streak would vaporise when he appeared.

‘We were petrified of George,’ Rob recalled. ‘George was a strict disciplinarian and, to be honest, everyone was scared of him. I think he saw me as a bad influence on Richard. I think today I’d have been diagnosed with ADHD, but back then we were being sent out of the classroom a lot. Notes were going back to parents and George was concerned about our relationship.’

Rob and his other mates did their best to have fun with Richard’s ability to lip-read and would also take advantage of his mercurial swiftness to anger. Rob, for instance, would noiselessly mouth things like ‘You’re an idiot’ across the room to Richard. He would respond with a shake of his fist or some choice words of his own, often spoken too loudly. He would then be admonished by the teacher: ‘Richard, what is going on? Calm down!’

At primary school, the pair often ended up down in the hall to be disciplined. Later, when they left Maori Hill to attend Balmacewen Intermediate School, their disruptiveness saw them sent to different classrooms for their own good.

Richard was not always the innocent, easily agitated victim. He was sometimes also the architect of his own fate. On one occasion, he drew a picture of their teacher sitting on a toilet. The small sketch went from hand to hand around the classroom until the teacher caught one of them red-handed. ‘She was not amused and I got sent out for a moment with the headmaster,’ Richard said.

It may have been on that trip down the corridor to visit the headmaster that Richard showed his anti-authoritarian side. When asked by his friends what had happened, Richard shrugged. He’d turned off his hearing aids and lowered his gaze — he hadn’t heard or seen a word of the reprimand dished out to him!

Professional wrestling fascinated the boys — Richard loved its physicality and enjoyed demonstrating his considerable strength. One day, Rob got a little too boisterous and slammed Richard to the ground, knocking him unconscious. When he came to, he looked at Rob and asked why he’d come around to the Emerson house. He had no idea what had happened. When Ingrid came home, Rob had to explain the situation because Richard still remembered nothing.

After a quick trip to the hospital, Richard got a cautionary all-clear, but Ingrid had to wake him every hour during the night to make sure he hadn’t suffered a concussion.

In the morning, a tired but none-the-wiser Richard woke up to his mother’s inquiry: ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Fine,’ came his reply.

His sister Helen then popped her head in and asked, ‘How are you?’

‘Fine!’

Down at breakfast, George asked, ‘Are you feeling all right?’

‘I’m fine!!!’

At school that morning, Rob’s first words to Richard were, ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Everyone’s asking me that and I don’t know why!’

While Richard loved physicality, sport didn’t work for him. He did, however, find a passion for riding his bike as fast as possible.

I didn’t play much sport. I tried rugby, but it was a little bit problematic as to play it I had to take my hearing aids out. The first time I played, I grabbed the ball and ran across the field, thinking, ‘This is great, no one can tackle me!’ But I didn’t realise the whistle had been blown. So, rugby wasn’t a very good idea for me.

When we were kids, we all had push bikes and I loved to ride my bike fast. One day, my friends suggested we have a race around the grounds at John McGlashan College, a private school near where we lived. We were all on our bikes at the start line and someone said ‘Ready, set, go!’

I raced off, pedalling as hard as I could. I was ahead, I was in front. I couldn’t hear anything because the wind in my hearing aids was so loud. I knew I was pedalling hard because my back wheel was spinning in the wet grass; I was going to win this race.

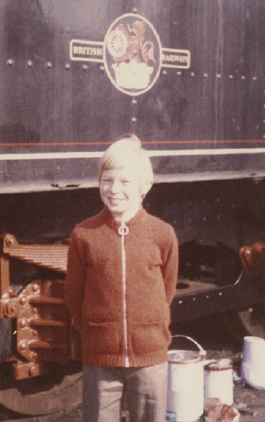

Richard and Helen in the Netherlands in 1974. George went on a sabbatical to Leicester and the family took the opportunity to travel through Europe.

I looked behind me and … faark! … There was no one there. My mates were nowhere to be seen. Suddenly, someone reached out and grabbed at my shoulder. It was the school’s groundskeeper. He asked me what I thought I was doing.

‘I was having a bike race …’ and I looked around for the others only to find I was by myself.

‘Get off that bike and walk!’ was his response. He then followed me out of the school grounds and up the road a bit.

I kept on walking until I came across my friends sitting outside the dairy laughing their heads off. It was then I realised what had happened. They knew I’d get caught by the groundskeeper, the bastards!

While it was another example of me being naïve and gullible and then ashamed, the irony is that having people play tricks on me like that helped me socially. I was always inquisitive and liked being with people who were fun, but when I was younger those same people would get me into trouble because I was a bit naïve. I became a source of amusement for them. If I had gone to a school for the deaf, I don’t think I would have developed the same social skills that I did.

Teasing and misbehaviour aside, Richard’s schooling remained normal, but his home life had some marked differences to those of his peers.

For starters, the Emerson family didn’t have a television — much to Helen’s ongoing annoyance. George had no time for TV, regarding it as frivolous.

Actually, the family did briefly have a television, which was given to them by Ingrid’s parents. Richard enjoyed watching the newsreader Philip Sherry, but little else.

‘He could lip-read Philip Sherry word for word because his face filled most of the screen,’ Ingrid recalled. ‘The reason my parents got us a TV was for Richard to watch cartoons and other children’s programmes, but he never seemed interested. I said to him, “Don’t you like that?” He replied, “No, they just go baa, baa, baa.” Of course, we then realised that you can’t lip-read cartoons, so he didn’t enjoy them.’

Much to George’s satisfaction, the television then disappeared.

Helen, of course, saw things differently. ‘The one thing that was different in our family is that we never had a TV when I was growing up. That was in part because Richard couldn’t follow what was going on; and later when it was suggested to my father that I might enjoy TV, he said it was all rubbish anyway. “We’re not having television in my house,” he’d say.

‘It was quite traumatic for me — everyone else at school would be talking about what was on TV last night and I couldn’t join in that conversation. I would read the Listener to get synopses of stories just to join in the conversation. I didn’t blame Richard for it — and I never felt sorry for him — it was just the way it was: we didn’t have a TV because Richard couldn’t understand it.’

The next television that came into the house was bought by Richard himself after he’d left school and started working.

‘Teletext must have just come in in the mid-eighties and there were some shows with closed captions,’ Helen said. ‘I think we were the only family that watched ’Allo ’Allo! with the subtitles done to reflect the fake French accents — that’s something most people don’t know, because who would watch ’Allo ’Allo! with subtitles?! But it opened up a whole new world for Richard.’

The lessons from John Caselberg, the teasing from his friends and even what he learned from watching TV made Richard hyper-aware of body language and what it can add to a conversation. For a lip-reader, ‘listening’ to someone with an expressive face can change the dynamic — a twinkle in the eye will indicate a joke, a glower will emphasise a verbal telling-off. One of the hardest things for Richard was trying to understand people with deadpan faces. He much preferred his friends and his TV characters to be exuberant and animated.

I used to go to the movies, but I could never pick up the dialogue. Anything with lots of dialogue is very hard to follow — but action movies are okay. When videos came out I would hunt around the video shop looking for movies with subtitles that I could watch, but that wasn’t always easy.

When DVDs came out — oh my god! — most of them came with subtitles and that was it for me. I loved it. Even better, Netflix. Life gets better as technology moves along. I’ve been able to go back and watch early movies and pick up the innuendo and inside jokes. I love the British comedies and my favourite is probably Death at a Funeral.

Long before subtitles, there was one show I could watch easily and I would watch a lot — Some Mothers Do ’Ave ’Em with Michael Crawford as Frank Spencer. He was very visual. He had an expressive face and moved a lot, going ‘Oooohh, ooohhh!’ It was quite dramatic.

Richard and Helen in Cologne, Germany.

I rely on body language a lot — I cannot pick up sarcasm in the way people speak, but I can pick it up from their body language and expressions. I’m not very good with people who do things with a straight face. I tend to stay away from deadpan faces as I can’t tell if they are pissed off with me or unhappy about something. It’s like trying to lip-read the radio. You can’t tell what mood somebody is in if the face is deadpan.

I can tell when people feel uncomfortable before they speak by the way they are moving or holding themselves. It’s not something that can be taught. People who have natural facial expressions are great for me. Rob Smillie was one of those people — he had a face I could easily read and that helped me a lot. I’m more inclined to be with people who are expressive and outgoing. I probably spend more time with extroverted people and not with people who have a radio face.

In 1974, George took a year’s sabbatical and the family moved to Leicester in England. The trip threatened to undo much of 10-year-old Richard’s learning as he was dropped into a foreign environment and a school system not attuned to his deafness.

He had inordinate trouble with a teacher from Ireland. Trying to lip-read a new ‘accent’ presented enough difficulty on its own, but the teacher was also an incessant cigarette smoker. As such, he’d developed a way of talking out of the side of his mouth that allowed him to smoke and talk at the same time. He also had a fiery temper. He and Richard failed to understand each other, resulting in heated clashes during Richard’s short time at the school and little successful learning.

Through it all, Richard learned a valuable lesson in the subtle variations of the English language. After time he could adjust to the Midlands accent and by the time he returned to New Zealand his own ‘English’ accent had changed as a result of trying to make himself understood.

Ingrid tells the story of Richard coming home from school at Leicester and she asked him what he’d had for lunch. ‘Harm and airgs,’ came his reply.

WHEN DVDS CAME OUT — OH MY GOD! — MOST OF THEM CAME WITH SUBTITLES AND THAT WAS IT FOR ME. I LOVED IT. EVEN BETTER, NETFLIX. LIFE GETS BETTER AS TECHNOLOGY MOVES ALONG.

I’ve learnt over the years how the vowels can change with accents and how foreign people show the vowels differently. I could lip-read Americans as they had this long drawl on the ‘a’ vowels and a tendency to stretch the words out somewhat, making the word I know seem much longer than it is.

When we were living in Leicester in 1974, I had to attend Lindon Junior Primary School. Initially, it was strange being in this school where everyone spoke quite differently. The words were there, but they sounded odd. It took me a wee while to grasp the local dialect. Words like the model train manufacturer ‘Hornby’ sounded like ‘Hon-bee’ and ‘cup of tea’ came out like ‘coup o teeea’.

Back in New Zealand after a year in the UK, my mother noticed that I had taken on a slight English accent. Recently, I impressed my workmates when I was listening to/lip-reading an English woman at the brewery. After a few moments, I asked her if she was from Yorkshire. Taken aback, she said, ‘Why, yes, I am. How did you know?’

I explained that I had lived in the UK for some time and had got to know some of the dialects that could be lip-read. My workmates were gobsmacked and disbelieving, wondering ‘How can Richard pick this up?’

While the gift of a television from his grandparents didn’t quite work out for Richard, another present they gave him hit the spot. They bought Richard a large tape deck — with the idea he’d play music on it — but instead he used it to record the sound of steam engines onto blank cassettes.

‘He loved the rhythm of the engine,’ Helen said, ‘and he’d record these trains for his listening pleasure at home afterwards — the problem was he played it so loud the rest of us had to listen to it as well.’

Ingrid’s parents also gave Richard his first taste — and love — of beer. Erik and Catherine Holst bought an old railway house in Bainesse, a location too small to even call itself a village, between Palmerston North and Himatangi Beach. The house, which sat on a large section, had been abandoned after a highway had been rerouted. It became the Holst holiday house during Ingrid’s childhood and later her parents retired there.

When Richard was 10, he got his first taste of beer, a sip of his grandfather’s home brew, when visiting Bainesse one summer. ‘We were cutting grass with a scythe,’ he remembers. ‘And Grandfather came down the path carrying a tray of glasses and a bottle of beer. I can still remember that first taste of beer — bitter but malty.’

It’s no surprise Richard remembered the moment so well — even at a young age he had an obsession with food and flavours. When he was young, an Indian family lived next door to the Emersons. The Mukherjee family had come to Otago from Sweden. Their daughter Sutapa was a year younger than Richard to the day. Richard loved the smells that would waft from next door and he developed a taste for Indian food from an early age. The more spicy and garlicky the better.

Another family introduced the Emersons to Thai green curry, which Richard kept demanding his mother make. Macadamia nuts introduced by another biochemistry staffer who arrived from Hawaii tantalised Richard’s taste buds. He also loved walking around Dunedin smelling the odours of the city —the Cadbury chocolate factory, the instant coffee production at Gregg’s, where he would later work, and the produce at the Chinese greengrocers.

An extended family portrait, including New Zealand’s first celebrity chef, Alison Holst (third from right at the back), who married Ingrid’s brother Peter Holst (holding the baby).

He also had access to one of this country’s culinary giants — his aunt, Alison Holst. As Alison Payne, she’d grown up in Dunedin, the eldest of three now-famous sisters: Clare Ferguson is a London-based food stylist and writer, and Patricia Payne is a renowned opera singer. While studying home science at Otago, Alison met Ingrid’s brother Peter, who was studying medicine, and the pair married. She was then plucked from nowhere to do cooking demonstrations on television, replacing the original Kiwi celebrity chef, the Galloping Gourmet, Graham Kerr. Alison and Peter were among the first shareholders in the brewery.

A lot of people don’t know Alison Holst is my aunty. I remember going up to her place in Karori in Wellington. She had a small kitchen at the back of the house, but she didn’t stay in the kitchen. She’d bring the chopping board into the lounge and chop vegetables while talking to us. She was always well-spoken — she was an impressive woman, very dynamic.

Richard and Helen.

I loved the way she was able to make food from what you had in the cupboard rather than having to get exotic ingredients — she came up with recipes that actually worked. Her son, Simon, my cousin, is very good too, especially his bread recipes.

I was aware at a young age that I had a better sense of smell than other people. I loved spices and garlic. To me, smell and taste was a language. It tells a story and can be quite exciting. I love the smell of coal from the steam engines.

Smell in food helped me to think of flavours in beer. Once, I had a bottle of gueuze — a Belgian-style sour beer, pronounced gooze — and it had a smell that I knew was a smell from my childhood in Dunedin. I had this memory of a smell, but I couldn’t for the life of me remember where it was from. It wasn’t from another beer — I knew it was from my childhood. I was thinking, ‘Where have I smelt that?’ but I couldn’t get it.

Then a couple of weeks later — Eureka! Eureka! It was from the Kingston Flyer. There’s a balcony carriage called the birdcage with five or six small compartments each with leather seats. When you sat down a puff of air came out — Whap! — and this smell came with it. The seats were stuffed with horse hair and that was the smell of the gueuze. That’s how evocative a sense of smell can be — until then, I’d never thought of connecting a bottle of beer with the Kingston Flyer!

Richard embraced trains wholeheartedly — the size, noise, smell, heat, the clouds of steam, the visceral nature of giant gasping, puffing beasts — appealed to the side of his personality that also loved textured, operatic music. For a long time, he dreamed of becoming a steam train driver but soon realised he’d been born in the wrong time for such a calling. By the time he was old enough to operate a train, steam engines had gone, replaced by diesel and electric engines, and to be certified, train drivers needed good hearing because much of the operation relied on radio communication.

Richard made do instead with model railways. His original set, a gift from Santa one Christmas, included a little blue tank engine and a few wagons that looped his bedroom floor. His grandparents also had a small train set that had belonged to George and his brothers. It had two parallel tracks circling each other and it gave Richard hours of amusement as he tried to build a train long enough so the engine could almost ‘catch its tail’.

Over a period of years, George dug out a basement under the family home to create a new laundry, an extra toilet and a photographic darkroom. Using a pick and shovel he carted countless wheelbarrow-loads of soil up to a skip.

Once cleared, George saw the space had room for a model railway, which was duly set up. Richard spent hours in that room reading through the vast collection of model railway magazines his father and grandfather had accrued over the years.

The railway construction helped Richard develop the kind of problem-solving skills he’d need when he started his brewery operation on the whiff of some old hops a few years later. It also created an environment where he could work at his own pace, teaching himself at a comfortable but meticulous speed in contrast to what felt like the flurry of instructions he received at school.

As an educational tool, the model railway proved invaluable, with Richard teaching himself basic electrical wiring, soldering and woodwork. He designed the track layout, incorporating a rack railway to take the train up a steep incline, designed as a reminder of a family holiday to the Swiss Alps in 1974. To recreate the setting, Richard built an alpine mountain out of chicken wire, plaster of Paris and foam rubber. When completed, it was so high it almost touched the ceiling.

He covered a frame of wood and chicken wire with papier-mâché. Over that he whipped up batches of plaster of Paris to smear over the papier-mâché. He created vertical rock faces using tinfoil from his mother’s kitchen as a mould, filling it with plaster and removing the foil when it was semi-dry. His most challenging task came when he decided to put clumps of green tussock on the side of the mountain. One of his magazines suggested using foam rubber that had been dyed green.

Para Rubber was the first stop to buy the right kind of foam, not the polystyrene bubble stuff, but the stuff they use to make foam mattresses. The next step was to cut the foam into fine pieces. First, I cut it into small chunky bits with scissors then I put them in my mother’s blender … At first, it was interesting to observe the dry foam bouncing off the sharp blades. Hmmm, I needed to try something else to render the bits smaller. I thought, ‘Why not freeze the foam with water then whizz it?’

Yes, that was a step in the right direction, though it took a while for the foam to dry out. The final step was to dye the blitzed foam with green clothes dye … Bingo! I’d done it!

Richard was always happy when he was around trains.

But I couldn’t use my mother’s blender for much longer as I could see she wasn’t impressed with little bits of foam lingering around the kitchen. However, my education was complete: I’d learnt something and got it right!

That model railway was an important part of my growing up. Unfortunately, it fell into disrepair the moment I started developing Emerson’s Brewery as the time available for working on it became less and less. There would be the rare occasion where Dad and I would have a beer or two and run a few trains over the layout.

One of the last times we operated the layout together was when George was still able to venture down to the basement. He was suffering from a brain tumour and his balance was not that good. We ran his favourite little acquisition, a scale model New Zealand Railways F Class steam locomotive. It was a pleasure to operate it for him, though a little painful for me to see him struggling to appreciate the little engine because he couldn’t see too well at that time.