THIS CHAPTER WILL EXAMINE BOTH BEST PRACTICES and promising practices in the child welfare system. The first section will provide a discussion of five key decision points in the child welfare process: (1) reporting child abuse and neglect; (2) referring the report for investigation; (3) investigating the referral; (4) removing the child from the home, including the court process; and (5) exiting the system. Prior work has demonstrated that European American children have better outcomes at each of these decisions points than children of color (Caliber Associates 2003; Lemon, D’Andrade, & Austin 2005; Harris & Hackett 2008). The second section will discuss what children need to achieve optimal growth and development. Section three will focus on ecological systems theory and attachment theory, as well as factors in the microsystem that impact outcomes for disadvantaged children of color in the child welfare system. Best practices/interventions that are needed at key decision points when working with children and families of color will be explored. There will also be a discussion of risk factors, particularly the risks for those children of color who enter the system with histories of insecure attachment, severe maltreatment, and early trauma and loss, and what children of color and their families don’t have and need vis-à-vis policies and interventions; in addition, protective factors will be examined. Finally, the fourth section will focus on the significance of ongoing cultural sensitivity and competency training for child welfare practitioners, supervisors, administrators, and child protective services (CPS) workers. Examples of a cultural competency self-assessment instrument and a cultural competency training module are included. This section will culminate with the presentation of a best practice case scenario.

KEY DECISION POINTS IN THE CHILD WELFARE SYSTEM

Research has shown that children of color are disproportionately represented and have disproportional outcomes at key decision points in the child welfare system (Hill 2001; Caliber Associates 2003; Bowser & Jones 2004; Hines, Lemon, & Wyatt 2004; Harris & Skyles 2005; Harris & Hackett 2008). The initial key decision point is a call to CPS raising an allegation of child abuse and/or neglect.

Reports of Child Abuse and/or Neglect

The call to CPS to report child abuse and/or neglect can be made by a family member, friend, neighbor, or one of the individuals designated as a mandated reporter (teacher, school counselor, school principal, emergency medical personnel, nurse, physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, medical examiner, dentist, police officer, district attorney or assistant district attorney, substance abuse counselor, social worker, and child care worker). Most reports are made by mandated reporters, who are required by law to report any suspected cases of child abuse and/or neglect to CPS; however, laws vary from state to state. In 2007 approximately 57 percent of child abuse reports came from teachers, lawyers, police officers, and social workers (Iannelli 2010).

Children from any racial or ethnic group can be victims of child abuse and/or neglect. “In 2007 one-half of all victims of child abuse and neglect were white (46.1%), one fifth (21.7%) were African American and one-fifth (20.8%) were Hispanic” (Iannelli 2010, 1). The preponderance of evidence demonstrates that cases involving children of color are reported, investigated, and substantiated and result in the ultimate placement of these children in out-of-home care at higher rates than in cases involving white children; however, rates of child abuse are not higher for children of color when compared to white children.

At the crux of the process for mandated reporters is the legal mandate to report suspected cases of child abuse and/or neglect; the focus is on reporting. There are obviously objective criteria (bruises, slap marks, welts, lacerations, bite marks, scald burns, contact burns [e.g., from cigarettes, irons], and bone injuries) that can be utilized in deciding to make a report to CPS. However, subjective criteria (e.g., family isolation, attitude of parent, lack of financial resources, delays in seeking medical attention for a child due to lack of health insurance) also play a major part in the decision to report allegations of child abuse and/or neglect. The utilization of subjective criteria opens the door for other factors—such as stereotypes, racial biases, prejudices, false assumptions, and misconceptions—to influence the decision to report suspected cases of child abuse and/or neglect to CPS. Exposure/visibility bias has also been identified as a reason for the high rates of reports to CPS by mandated reporters for children of color (Chand 2000).

According to this view, because children from African American and Native American families are more likely to be poor, they are more likely to be exposed to mandated reporters as they turn to the public social service system for support in times of need. Problems that other families keep private become public as a family receives Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), seeks medical care from a public clinic, or lives in public housing.

(Cahn & Harris 2005, 6)

Referral of Reports for Investigation and Investigation of Referrals

The second and third key decision points are referral of the report for investigation and investigation of the referral by a CPS worker to determine whether or not to substantiate the allegation after completion of an investigation. Cases involving children of color are opened for investigation and substantiated at higher rates than cases involving white children (King County Coalition on Racial Disproportionality 2004; Lemon, D’Andrade, & Austin 2005; Johnson et al. 2007; Harris & Hackett 2008; Washington State Racial Disproportionality Advisory Committee 2008). There is also evidence of higher substantiation rates of child abuse and/or neglect for Latino or Hispanic children than for non-Hispanic white children (Church, Gross, & Baldwin 2005; Church 2006). Lemon, D’Andrade, and Austin (2005) examined cases in five states and found that African American children had a 90 percent investigation rate versus a 68 percent investigation rate for white children; the rate for Hispanic children was 53 percent, and children of “Other” ethnicities had an investigation rate of 67 percent; white children always had lower investigation rates in all five states when compared to African American children.

Placement in Out-of-Home Care

Another key decision point in the child welfare system is placement in out-of-home care once a suspected case of child abuse and/or neglect is substantiated. Research has consistently demonstrated that children of color have higher rates of placement in out-of-home care, multiple placements during their time in out-of-home care, and longer stays than white children in out-of-home care. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1997), 57 percent of African American children were placed in out-of-home care, but 72 percent of white children remained in their homes and received in-home services. In Washington State African American children and Native American children were more likely than white children to be removed from their homes and placed in out-of-home care, and they remained in out-of-home care longer than white children (Washington State Racial Disproportionality Advisory Committee 2008). Findings from a study in Illinois revealed that 38 percent of white children were placed in out-of-home care compared to 53.7 percent of African American children (Lemon, D’Andrade, & Austin 2005).

The Court System

The court system plays a major role in all child abuse and neglect cases. Dependency court, also referred to as juvenile court and family court, typically has jurisdiction over cases of child abuse or neglect. This court’s primary focus is the safety, stability, permanency, and best interest of the child. Judges in dependency court have a responsibility to make decisions that will protect children from risk of future abuse or neglect.

The initial hearing is the most critical stage in the child abuse and neglect court process. The main purpose of the initial hearing is to determine whether the child should be placed in substitute care or remain with or be returned to the parents pending further proceedings. The critical issue is whether in-home services or other measures can be put in place to ensure the child’s safety. At the disposition hearing, the court decides whether the child needs help from the court and, if so, what services will be ordered. Placement is the key issue at the disposition hearing. The child can be:

• Left with or returned to parents, usually under CPS supervision

• Kept in an existing placement

• Move to a new placement

• Placed in substitute care for the first time if removal was not previously ordered

• As part of its reasonable efforts inquiry, the court needs to scrutinize carefully any CPS recommendation that the child be placed outside the home

(Jones 2006, 4)

Some children and families of color have encountered problems in dependency court. For example, many fathers have been marginalized or ignored. The following is a response from a caseworker who participated in a research study conducted by Johnson and Bryant (2004):

I find amongst African American fathers, even if they have a criminal record that is even fifteen years old, judges will shut down. Whereas if the man [father] is white, the court is more likely to overlook the criminal record, look at his family as well, and think about the resource that the father could be. (178)

There have also been reports of racist practices by judges. For example, a judge in a Texas court threatened a young Latina mother with removal of her child and placement of the child in the father’s care unless she agreed to speak only English in her home (Verhovek 1995). Several participants in the King County, Washington, racial disproportionality study (King County Coalition on Racial Disproportionality 2004) said they felt intimidated when interacting with judges, attorneys, and other court officials.

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges has been proactive in its work to determine what changes need to be made in dependency court to reduce racial disproportionality, as well as disparate treatment for children and families of color.

The complexity and significance of this issue points to the critical need for collaborative efforts to not only further study the factors that contribute to racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system, but to also design and implement specific actions that courts and child welfare system stakeholders can take to reduce these inequities and ultimately improve outcomes for all children and families. The Courts Catalyzing Change: Achieving Equity and Fairness in Foster Care Initiative (CCC) brings together judicial officers and other systems’ experts to set a national agenda for court-based training, research, and reform initiatives to reduce the disproportionate representation of children of color in dependency court systems.

(National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges 2011, 1)

National studies have repeatedly shown that a large percentage of children enter the child welfare system because of neglect by parents who abuse alcohol and/or drugs. In 1994 Family Dependency Treatment Court was started in Reno, Nevada, to handle cases of child abuse and neglect that involved a birth parent or caregiver who had a substance abuse problem. This model has been replicated in other states across the country. Many of the disproportionate number of children of color involved in the child welfare system have a parent who has a substance abuse problem; the implementation of this model has resulted in lower recidivism rates, decrease in the use of drugs, increase in reunification rates for families because parents are able to regain or able to get custody of their children, increase in education as well as vocational training and job placements for parents involved in family drug court. “Family drug courts emphasize treatment for parents with substance abuse disorders to aid in reunification and stabilization of families affected by parental drug use. These programs apply the adult drug court model to cases entering the child welfare system that include allegations of child abuse or neglect in which substance abuse is identified as a contributing factor” (National Criminal Justice Reference Service 2013, 1).

There have also been issues with state and tribal courts regarding Native American children and families (e.g., variation by state courts in their interpretation of the Indian Child Welfare Act [ICWA] and failure to transfer ICWA cases to tribal courts). “Some state courts have modified the definition of ‘Indian child,’ in contradiction to the language contained in the federal ICWA, thereby creating exceptions to who is an ‘Indian child’ and to whom federal protections under ICWA apply” (Horne et al. 2009, 5).

The Pew Commission has made the following recommendations to strengthen dependency courts in this country:

• Courts are responsible for ensuring that children’s rights to safety, permanence and well-being are met in a timely and complete manner. To fulfill this responsibility, they must be able to track children’s progress, identify groups of children in need of attention, and identify sources of delay in court proceedings.

• To protect children and promote their well-being, courts and public agencies should be required to demonstrate effective collaboration on behalf of children.

• To safeguard children’s best interests in dependency court proceedings, children and their parents must have a direct voice in court, effective representation, and the timely input of those who care about them.

• Chief Justices and state court leadership must take the lead, acting as the foremost champions for children in their court systems and making sure the recommendations here are enacted in their states. (Horne et al. 2009, 8–9)

These recommendations have resulted in improvements in dependency courts in many jurisdictions across the country (Edwards 2011; Office of Children & Families 2009; U.S. Children’s Bureau 2006); however, there is still work to be done because children and families of color continue to have a disproportionate number of cases in dependency courts in states throughout this country and also continue to receive disparate treatment in many dependency courts.

SERVICE DISPARITIES

Disparities in services are another major challenge for children and families of color once a case has been substantiated for child abuse or neglect and a child is removed from the care and custody of a birth parent and placed in out-of-home care. The weight of the evidence continues to show that race impacts the quantity and quality of services for children and families of color once they enter the child welfare system (Olsen 1982; Close 1983; Maluccio & Fein 1989; Harris & Skyles 2005; Harris & Hackett 2008). According to Olsen (1982), Native American families had the least chance of being recommended to receive services when compared to all other ethnic groups. Courtney et al. (1996) reported a prevailing pattern of racial and ethnic disparity in the provision of child welfare services. According to Cross (2008) and Rivaux et al. (2008), children of color are more likely to be removed from their homes and placed in out-of-home care and less likely to receive services once they enter out-of-home care.

Exiting the Child Welfare System

The final key decision point is exiting the child welfare system. Children of color easily enter the child welfare system in disproportionate numbers when compared to white children. However, they encounter extreme difficulty exiting the system. Johnson et al. (2007) found that when an African American child and a white child enter the child welfare system for the same reason, the odds of reunification for an African American child were 1.19 times the odds for a white child. Findings in a December 2011 Applied Research Center (ARC) report titled Shattered Families revealed that the detained or deported families of approximately 5,100 children currently placed in foster care were experiencing “insurmountable barriers” in their family reunification efforts (Cuentame 2011):

Ovidio and Domitina Mendez lost their five children to foster care when the Georgia Department of Family and Children Services arrived at their home [and] claimed the kids were malnourished. The couple, who are both undocumented immigrants from Guatemala, says they did everything the child welfare agency asked them to do to get their kids back. …

According to the family and to advocates in Georgia, the Mendez family are the victims of a biased child welfare system that denies undocumented and non-English speaking mothers and fathers their parental rights. …

The ARC investigation … found that undocumented parents face bias in the child welfare system, even when parents are not detained or deported. This is partially a result of cultural and language discrimination against immigration parents. Wessler (2011) reports:

Questioning about English came quickly during the June termination-of-rights hearing, according to court documents. Then came questions about the parents’ immigration status.

“Describe for the court why even three years after [the children went into the state’s custody] you cannot speak English without an interpreter,” Bruce Kling, special assistant attorney general for Whitfield County Department of Family and Children’s Services, said to Domitina Mendez.

“I cannot speak English, but I did—because I did not grow up speaking English,” she said through an interpreter. …

Though the couple completed the child welfare department’s reunification case plan tasks and even the children’s attorney believed that the family should have been reunified, the judge who presided over the case ruled to terminate their parental rights. (1)

Findings from Harris and Hackett (2008) revealed that race impacted the availability and delivery of services, resulting in disproportionate numbers of children of color entering the child welfare system and remaining in the system longer when compared to white children.

African American and Native American children are often placed in kinship care when they enter the child welfare system. When children of color are placed in kinship care, these placements often last longer, and these children are impacted by service disparities during their longer stay in these placements. Findings from Needell et al. (2004) revealed the median length of stay in kinship care for children to be as follows: African Americans, 854 days; Hispanics, 649 days; Asians, 539 days; and whites, 546 days. Family reunification is also impacted by family structure, especially for children who are members of single-parent families. Harris and Courtney (2003) found the following in their study of children in the California child welfare system:

• Males were slightly less likely to be reunified than females.

• Infants and adolescents were reunified more slowly than children of other ages.

• Children removed from home because of neglect returned home at a slower rate than children removed for other reasons.

• Child health problems slowed the rate of reunification.

• Children in kinship foster homes and foster family homes returned home more slowly than children in other placement types.

• African American children were reunified at a slower rate than other children.

• Children from two-parent families were returned home more quickly than children from single-parent homes, regardless of the gender of the single parent. (423)

It is clear that children of color continue to be disproportionately represented at each key decision point in the child welfare system from the initial call to CPS to their exit from the system. According to Cross (2008),

The real culprit appears to be our own desire to do good and to protect children from perceived threats and our unwillingness to come to terms with our own fears, deeply ingrained prejudices, and dangerous ignorance of those who are different from us. These factors cumulatively add up to an unintended race or culture bias that pervades the field and exponentially compounds the problem of disproportionality at every decision point in the system. (12)

OPTIMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF CHILDREN

One of the primary goals of child welfare is preservation of the relationship between children and their parents. This relationship between children and their parents impacts the growth and development of all children, regardless of their racial or ethnic background. Child development is also impacted by socioeconomic status. From a life-span perspective human development, including child development, is based on the following premises: (1) development is a lifelong process, (2) development is multidimensional and multidirectional, (3) development is plastic, (4) development has contextual influences, and (5) development is multidisciplinary (Baltes, Smith, & Staudinger 1997; Smith & Baltes 1999). Key stages in development include infancy, toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, early adulthood, middle adulthood, and late adulthood.

Children develop physically, cognitively, emotionally, and socially. Every child develops at her or his own pace. However, a child’s early relationships play a crucial role in brain development. According to the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2007), children who have healthy and stimulating experiences will have “brain architecture” that maximizes its greatest genetic power; however, when children’s lives are filled with adversity, their brain architecture is weakened and cannot operate at maximum capacity. Many children of color have numerous adverse experiences once they enter the child welfare system, and these experiences are harmful to their developing brain architecture.

The child welfare system is typically characterized by cumbersome and protracted decision-making processes that leave young children vulnerable to the adverse impacts of significant stress during the sensitive periods of early brain development. The powerful and far-reaching effects of severely adverse environments and experiences on brain development make it crystal clear that time is not on the side of the abused or neglected child whose physical and emotional custody remains unresolved in a slow-moving bureaucratic process. The basic principles of neuroscience indicate the need for a far greater sense of urgency regarding the prompt resolution of such decisions as when to remove a child from the home, when and where to place a child in foster care, when to terminate parental rights and when to move towards a permanent placement. The window of opportunity for remediation in a child’s developing brain architecture is time-sensitive and time-limited.

(National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2007, 6)

It is very clear that time is of the essence when decisions are made to remove children from their birth families and place them in out-of-home care, especially children of color who continue to enter the child welfare system in disproportionate numbers and remain in the system for extensive periods of time. The brain is especially reactive to environmental influences during early infancy and childhood. Optimal brain development is promoted by nurturing and responding parents and/or caregivers, good stimulation, and positive environmental experiences. Synapses are being produced by the brain during this period of early growth and development, and they need to be stimulated because a pruning process is also occurring. Synapses are “pruned away” during the stages of childhood and adolescence if they do not receive stimulation (Huttenlocher & Dabholkar 1997).

• The architecture of the brain depends on the mutual influences of genetics, environment, and experience.

• Early environment and experiences have an exceptionally strong influence on brain architecture.

• Different mental capacities mature at different stages in a child’s development.

• Sensitive periods occur at different ages for different parts of the brain.

• Stimulating early experiences lay the foundation for later learning.

• Impoverished early experience can have severe and long-lasting detrimental effects on later brain capabilities.

• Stressful experiences impact the functioning and architecture of specific neural circuits in an adverse way.

• Brain plasticity continues throughout life. (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2007, 1–4)

It is imperative for child welfare professionals at key decision points in the child welfare system to realize that a child’s relationship to her or his birth parents and/or caregivers plays a major role in the development of the child’s brain architecture, as well as in her or his developmental outcomes across the life span. Loving, sensitive, and nurturing parents or caregivers are essential for children to have optimal growth and development. Birth parents and/or caregivers must be supported in their efforts to provide a safe and nurturing environment for children to grow and develop to their maximize potential.

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS THEORY AND ATTACHMENT THEORY

Ecological Systems Theory

Ecology is the science that focuses on the relationships between organisms and their environments. It facilitates taking a holistic view of individuals and their environments as a unit in which neither can be fully understood except in the context of its relationship to the other. The relationship is characterized by continuous reciprocal exchanges in which individuals and their environments influence and shape each other. Human beings try throughout life for the best fit between themselves and their environment.

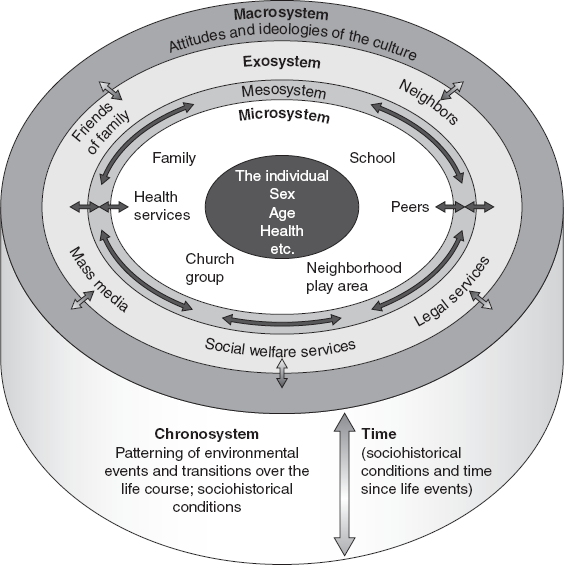

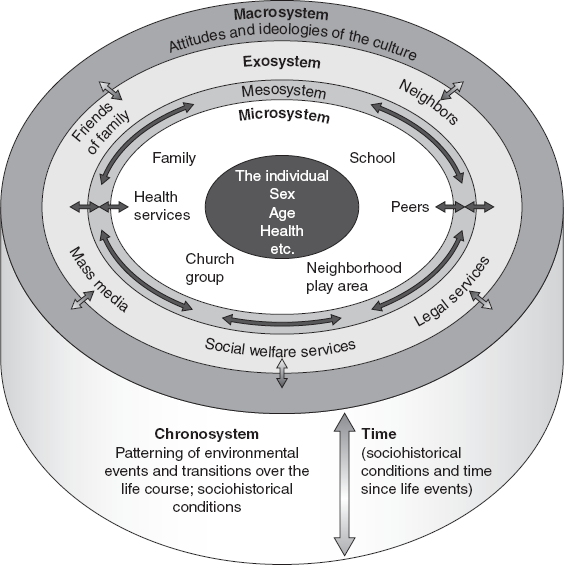

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979, 1989, 1993) as well as Bronfenbrenner and Evans (2000) view the individual as developing within a system of interrelationships and interconnections that are impacted by five systems or contexts in the environment. According to this ecological model of human development, each child is at the center of these systems or contexts, which can be conceptualized as environments and which influence each other and are ultimately influenced by culture. This model is also referred to as the bio-ecological model.

The five systems or contexts that influence a child’s development are as follows. Microsystem refers to a pattern of activities, roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing child in a particular setting. Mesosystem refers to the interrelations among two or more settings in which the developing child actively participates. Exosystem refers to one or more settings that do not involve the developing child as an active participant; however, events occur in these settings that affect the developing child. Macrosystem refers to the culture or subculture of the developing child, along with any belief systems, values, and ideologies and the sociopolitical, historical, economic, and environmental forces that impact the developing child’s overall well-being. Chronosystem refers to changes and transitions in the child’s environment throughout her or his life course (Bronfenbrenner 1986; Bronfenbrenner & Evans 2000; Bronfenbrenner & Morris 1998).

It is important to remember that each child of color who enters the child welfare system is at the center of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system (see figure 3.1), interacting directly with individuals in the microsystem and being impacted by other systems in her or his environment. In addition, all of the aforementioned, including the child, are constantly changing as the child grows and develops.

Ecological systems theory can be used to assess the numerous factors that impact children who enter the child welfare system because of child maltreatment. It is imperative to understand the impact of child maltreatment on the growth and development of children. Ecological systems theory shows all the systems or contexts that affect the developing child before and after entry into the child welfare system.

Attachment Theory

Another theory that is significant in working with the disproportionate number of children of color who enter the child welfare system is attachment theory. Attachment theory grew out of ethology, developmental psychology, and psychoanalysis. According to Bowlby (1969, 1977a, 1977b), attachment is an essential process in human ontogeny and impacts development across the life span. It is essential for a child to have a continuous attachment to a primary caregiver because the child’s patterns of attachment impact not only development but also relationships across the life span. Self and object representations begin in childhood and continue throughout adult life. According to Blatt and Lerner (1983), “the development of the representational world into a cohesive and integrated sense of reality initially occurs within the context of the primary caretaking relationship. Eventually this context expands to include significant others” (25). These significant others are part of a “small hierarchy of major caregivers” (Bretherton 1980, 195).

FIGURE 3.1 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems categories.

Source: J. W. Santrock. (2004). “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory of Development.” Life-Span Development (p. 55). Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Permission to Reprint: McGraw-Hill.

The core of attachment theory is “internal working models” (Bowlby 1973).

In the working model of the world that anyone builds, a key feature is the notion of who his attachment figures are, where they may be found, and how they may be expected to respond. Similarly, in the working model of the self that anyone builds a key feature is his notion of how acceptable or unacceptable he himself is in the eyes of his attachment figures. … Confidence that an attachment figure is … likely to be responsive can be seen to turn on two variables: (a) whether or not the attachment figure is judged to be the sort of person who in general responds to calls for support and protection; (b) whether or not the self is judged to be the sort of person towards whom … the attachment figure is likely to respond in a helpful way. Logically these variables are independent. In practice they are apt to be confounded. As a result, the model of attachment figure and the model of self are likely to develop so as to be complementary and mutually confirming.

(Bowlby 1973, 203–204)

Consequently, the child’s internal working models are highly dependent on the caliber of the relationship to the primary caregiver, including the responsiveness of the caregiver to the needs of the child. Although a child can form new relationships during her or his life span, one of the assumptions of attachment theory is that internal working models that begin in the early stage of development tend to be significant as a child grows and develops. “Although these mental representations continue to evolve as individuals develop new relationships throughout their lives, attachment theory assumes that representational models that begin their development early in one’s personal history are likely to remain influential” (Harris 2011, 43).

Entry into the child welfare system disrupts the attachment relationship between a child and her or his primary caregiver, usually the child’s birth mother, and when this relationship is disrupted and/or lost, the child can experience irreparable harm. Attachment theory can be helpful in understanding the types of attachment that are prevalent in children when they enter the child welfare system. It can also help in understanding children’s issues of separation and loss when they experience a disruption in their primary attachment relationship because of placement in out-of-home care as a result of child abuse or neglect.

Ainsworth (1989) discussed the attachment bond as “entailing representation in the internal organization of the individual” (711). The attachment bond is a type of “affectional bond” that is reflective of “the attraction that one individual has for another individual” (Bowlby 1979, 67). According to Ainsworth (1989), the individual is looking for security in her or his attachment bond with another individual. Ainsworth used the Strange Situation technique to study the responses of infants when they were separated from their mothers and their subsequent responses when they were reunited with their mothers. She delineated three types of attachment: “secure,” “avoidant,” and “ambivalent or resistant” (Ainsworth et al. 1978). Subsequently, Main and Solomon (1986, 1990) discussed the “disorganized/disoriented” type of insecure attachment in their research findings. The attachment research demonstrates the importance of the mother–infant relationship during the first year of life. However, children who enter the child welfare system have experienced some type of child maltreatment, and many of these children have a disorganized/disoriented type of insecure attachment. Family risk factors such as child maltreatment, parental mental illness, and/or parental substance abuse have been linked to an increase in insecure attachment, particularly the disorganized type (Egeland et al. 1991; Lyons-Ruth et al. 1991; Harris 2011).

Main and Goldwyn (1984) developed the Adult Attachment Interview protocol, including a four-category system for classification and scoring; the categories are secure/autonomous, dismissing, preoccupied, and unresolved/disorganized. The aforementioned classifications are important in work with the disproportionate number of children of color entering the child welfare system due to child maltreatment because this process results in the loss of their primary attachment relationship, as well as relationships with other significant family members. Research has also shown a correlation between the attachment classifications of parents and those of children (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy 1985; Hesse 1999; Riggs & Jacobvitz 2002). These studies show the significance of parental internal working models in forming attachments. Bowlby (1973) stated that one’s internal working model is a mental representation that gives one models of the workings, properties, characteristics, and behaviors of attachment figures, the self, others, and the world.

Risks and Resilience for Children Entering the Child Welfare System

There are risk factors associated with entry into the child welfare system and placement in out-of-home care. According to Keyes (2004), “risk factors are causes of undesirable, non-normative outcomes. Put differently, risk factors generate negative change in or persistent (i.e., chronic) poor behavior or functioning” (223). Children who enter the child welfare system experience the loss of a primary caregiver, as well as other members of their family, including siblings; siblings are often separated and placed in separate foster homes. They also experience the loss of their home, school, and neighborhood. For the disproportionate number of children of color entering the child welfare system there is the added risk of multiple foster care placements during their inordinate amount of time in out-of-home placement (Harris & Skyles 2005; Harris & Hackett 2008; Washington State Racial Disproportionality Advisory Committee 2008). Family environmental conditions that are internal (parental substance abuse) or external (parental unemployment) can adversely affect a primary caregiver’s or family’s ability to provide an environment that is conducive to the optimal growth and development of their at-risk children (Bergen, 1994).

It is a highly traumatic experience for all children who enter the child welfare system—but this is especially true for children of color because many of these children are already high-risk as a result of prior adverse and stressful life events. Furthermore, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2011), children can have problems across their life span if they have a traumatic experience and do not receive any type of treatment or intervention:

• More than 60 percent of youth age seventeen and younger have been exposed to crime, violence, and abuse either directly or indirectly.

• Young children exposed to five or more significant adversities in the first three years of childhood face a 76 percent likelihood of having one or more delays in their cognitive, language, or emotional development.

• As the number of traumatic events experienced during childhood increases, the risk for the following health problems in adulthood increases: depression; alcoholism; drug abuse; suicide attempts; heart and liver disease; pregnancy problems; high stress; uncontrollable anger; and family, financial, and job problems. (1–2)

However, with the appropriate intervention and support resilience can be seen in children when they are faced with a traumatic experience.

A link has been shown between adverse health outcomes in adults and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—i.e., physical, sexual, or verbal abuse, as well as family instability, including incarceration, mental illness, and substance abuse—by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010). “The high prevalence of ACEs underscores the need for 1) additional efforts at the state and local level to reduce and prevent child maltreatment and associated family dysfunction and 2) further development and dissemination of trauma-focused services to treat stress-related health outcomes associated with ACEs” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010, 1). Clearly, it is important to focus on resilience for all children who enter the child welfare system. However, a focus on resilience for children of color is important to facilitate better outcomes in light of their past traumatic experiences and the continued disadvantages they will encounter during their long stays in out-of-home care.

Children of color in the child welfare system need to be helped to develop resiliency skills. What is resilience? There are numerous definitions in the literature. Masten and Coatsworth (1998) define resilience as “manifested competence in the context of significant challenges to adaptation or development” (206). Resilience has also been defined by the American Psychological Association as “the ability to adapt well to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress” (Pizzolongo & Hunter 2011, 67). Children need protective factors to help them adapt and/or counteract adverse experiences in their lives—to become resilient. Protective factors are highly significant for those children who are at risk for child maltreatment (see table 3.1).

Protective factors can serve as a buffer for children who are at risk for child maltreatment. Sometimes children are at risk but still manage to have positive outcomes when faced with adverse factors in their family and/or environment. When children, even young children, have resilience skills, they react and cope in positive ways (Band & Weisz 1988). However, when children are in an environment that is considered high-risk, protective factors are essential for their physical, social, and emotional survival. Environmental protective factors needed are a stable and close-knit family, including extended family, as well as a strong and viable external system of social support; membership in or linkage to some type of church, faith in a higher source of power, or a sense of spirituality can also serve as a protective factor (Pinkney 1987; Ianni 1989; Wilson 1989; Pearson et al. 1990; Werner 2000). The key to survival for children of color in the child welfare system is the quality of their relationships within and outside their families and the availability of multiple networks of support.

TABLE 3.1 Risk and Protective Factors for Child Maltreatment

| RISK FACTORS |

| CHILD RISKFACTORS |

FAMILY RISKFACTORS |

ENVIRONMENTAL/COMMUNITY RISK FACTORS |

| Age |

Parental Substance Abuse |

High Rates of Crime |

| Temperament |

Parental Mental Illness |

High Rates of Unemployment |

| Physical and/or Developmental Challenges/Illnesses |

Social Isolation |

Low-Quality Schools |

| Level of Self-Esteem |

Low Socioeconomic Status |

Repeated Exposure to Racism, Bias, and Discrimination |

| Relationship with Primary Caregiver and/or Significant Others |

Single Parent with No Social Support System |

Lack of Child Care or Low-Quality Child Care |

| Lack of Social Support |

Domestic Violence |

Repeated Exposure to Crime/Violence |

| Poor Peer Relationships |

Insecure Parent–Child Attachment |

Homelessness |

| Premature Birth |

Parental Stress |

Lack of Residential Stability |

| PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

| CHILD PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

FAMILY PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

ENVIRONMENTAL/COMMUNITY PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

| Good Temperament |

Religious Faith or Spirituality |

Good Access to Health Care and Social Service Systems |

| Positive Peer Relationships |

Secure Parent–Child Attachment as Well as Stable Parental Relationship |

Good Social Connections and Supports in Community |

| High Intelligence Level |

Strong Extended Family Support |

Good Schools |

| Positive Early Social Experiences |

Gainfully Employed Parents |

Residential Stability with Healthy Communities |

| Good Developmental History |

Good Housing |

Middle or High Socioeconomic Status |

| Good Physical and Mental Health |

Consistent Family Rules and Structure |

Good Social Capital |

The best practice for the disproportionate number of children of color in the child welfare system is for professionals across systems to work from a child- and family-centered frame of reference at each key decision point. Alleviating the problem of the overrepresentation of children of color in the child welfare system does not require development of some type of “magical” program. It requires a paradigm shift from professionals across the board, and that shift means a team approach rather than the current fragmented and turf-based approach.

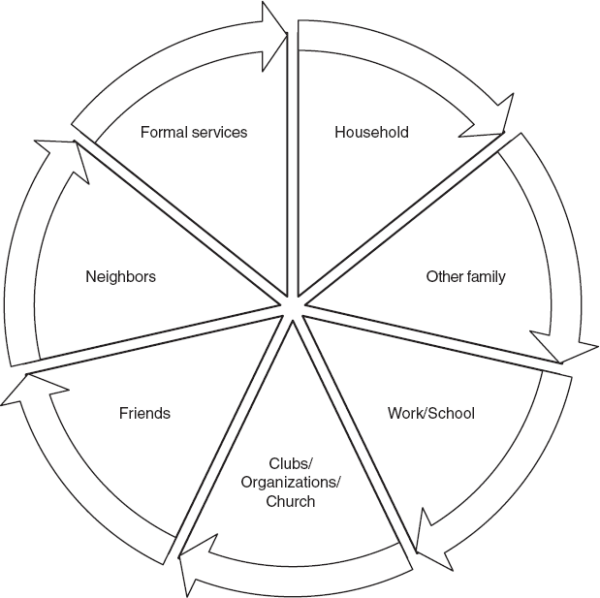

Many “professionals” are all about exerting their power with each other and especially with clients. Good child welfare practice means working with children and families so they will be empowered to enhance their level of functioning; it does not mean trying to “teach them a lesson” about how much power will be used in a negative way if they fail to do exactly as they are told by their child welfare worker and/or other professionals. Good child welfare practice also means working collaboratively with other professionals, agencies, and organizations in the community to do what is in the best interest of children and their families. For example, at the third key decision point in the child welfare system, when determining whether or not to substantiate an allegation of child abuse or neglect, is a comprehensive assessment of the child completed? The typical modus operandi is to complete some type of risk assessment utilizing a standardized tool—for example, structured team decision making. Of course, it is important to assess for child safety because no child should be in an environment where she or he is subjected to any type of child maltreatment. However, if there are supports within or outside the family that can keep a child and/or sibling group from entry into the child welfare system, it is crucial to do a comprehensive child assessment to identify these supports prior to bringing that child and/or sibling group into the system (see figure 3.2).

Differential Response Systems

The decisions to substantiate an allegation of child abuse and/or neglect and subsequently to remove a child from the care and custody of a birth parent or other family member(s) should be based totally on objective criteria and not based on stereotypes, biases, prejudices, and beliefs about children of color and their racial, ethnic, and/or cultural background; socioeconomic status; or distressed environment. A system of differential response should be in place for child welfare systems across the country at these key decision points. Yet only twenty-two states in this country have fully or partially implemented some type of differential response.

FIGURE 3.2 Social network map.

Source: E. M. Tracy and J. K. Whittaker. (1990). “The Social Network Map: Assessing Social Support in Clinical Practice.” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 71, 461–470. Permission to Reprint: Alliance for Children and Families.

“Differential response is a CPS practice that allows for more than one method of initial response to reports of child abuse and neglect” (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2008, 3). If a decision is made that a report is not very serious and the family simply warrants further assessment, the family is put on the “assessment track” and given an opportunity to engage in services that are more intense and culturally appropriate (Schene 2001). Differential response is more family-focused and less adversarial. Positive outcomes have been shown for families of color, as well as for white families (Institute of Applied Research 2004).

The following are the basic tenets of differential response systems:

• Assessment-focused. The primary focus tends to be on assessing families’ strengths and needs. Substantiation of an alleged incident is not the priority.

• Individualized. Cases are handled differently depending on families’ unique needs and situations.

• Family-centered. A strengths-based family engagement approach is used.

• Community-oriented. Families on the assessment track are referred to services that fit their needs and issues. This requires the availability and coordination of appropriate and timely community services and presumes a shared responsibility for child protection.

• Selective. The alternative response is not employed when the most serious types of maltreatment are alleged—particularly those that are likely to require court intervention, such as sexual abuse or severe harm to a child.

• Flexible. The response track can be changed based on ongoing risk and safety considerations. If a family refuses assessment or services, the agency may conduct an investigation or close the case. (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2008, 8)

It greatly benefits children of color if they are assessed prior to making a decision on their entry into the child welfare system. Assessment using a contextual model provides an objective and thorough view that allows analysis of all environmental systems and their reciprocal interactions (see figure 3.3).

Once children of color enter the child welfare system, all work should be directed toward expediting family reunification rather than allowing lengthy stays in the system. Although child welfare systems continue to state their commitment to family reunification, their actions are explicitly contrary to this stated commitment, especially for children of color. These children of color spend longer periods in out-of-home care when compared to white children, they grow up in and age out of the foster care system in substantial numbers, they and their families experience service disparities, they wait an inordinate amount of time for adoption, the services their birth parents receive to facilitate family reunification are lacking or nonexistent, and their birth fathers and paternal relatives are not involved in permanency planning.

Child’s Name: ____________________ Date: _____________

Social Stage

(Meeting and greeting the child)

Child’s Strengths

(Child’s perspective)

(Social worker’s perspective)

Presenting Problem

(Clear and concise statement of reason services are being requested for the child)

History of Presenting Problem

(Attempts to solve the problem—self, family, informal, and formal help)

Child’s Developmental History

(Discuss developmental milestones, risk and protective factors—child, family, and environmental/community)

Ethnic/Cultural Background

(Ask the child and family how they identify themselves and do not make assumptions based on physical appearance; include any significant extended family and/or community support systems)

Religious or Spiritual Beliefs

(Explore the child’s and family’s religious and spiritual beliefs, values, and activities; identify religious and/or spiritual supports/resources)

Social Supports/Relationships

(Discuss best friend, peers, persons the child turns to when in need of support, qualities that are significant when developing friendships)

Educational History

(Discuss in detail: Is the child functioning at appropriate grade level? Is the child in special education classes?)

Legal History

(Discuss in detail: Are there custody issues? If so, who has legal custody of the child? Are the child and/or family recent immigrants to this country? What are the child’s feelings regarding current legal/custody status and living arrangements? Is the child involved in a case that is currently open in family court or juvenile court? Who is the attorney of record?)

Play/Leisure Activities

(Explore play/leisure activities with the child and family)

Health History

(Explore past and current status of health, any serious illnesses, hospitalizations, etc.)

Client’s Role and Social Worker’s Role

(Discuss the role of the child and family, as well as your role in the helping process, including informed consent, confidentiality, etc.)

Schedule Next Session

(Plan date/time for session)

FIGURE 3.3 Child Assessment Format.

One long-standing practice that is definitely not a “best practice” is that of mandating in the service plan that each birth parent in the child welfare system complete a generic parenting course. First of all, it is erroneous to assume that every birth mother or father in the child welfare system needs to complete a generic parenting course. Second, a thorough assessment of parenting skills needs to be made prior to recommending any type of parenting course. Finally, after an objective assessment of parenting skills has been completed and the worker and parent agree that a parenting course is needed prior to family reunification, every parent of color should be referred to a culturally specific or culturally sensitive parenting course. Culturally specific parenting courses include the following: Los Niῆos Bien Educados, CCICC’s Effective Black Parenting Program, and Nurturing Parenting (curriculum materials are available for English, Hispanic, Kreylo, Arab, Hmong, Chinese, and African American families). The Strengthening Families Program is a culturally sensitive parenting program that is not culturally specific; it has proved to be successful with African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and American Indian families; it has also been translated for work with Chinese, Dutch, French, Russian, Spanish, Portuguese, Swedish, and Thai families. There is also a Strengthening Hawaii’s Families Program.

Programs Serving At-Risk Children and Youth

There are a number of programs that are currently serving children and families of color in communities across the country, and for some reason child welfare professionals have been remiss in their utilization of many of these programs. For example, a multitude of churches exist in most high-risk communities that have programs in place for children and families. Yet many child welfare professionals don’t bother to explore the communities where they work; consequently, they are clueless as to services that exist outside their sometimes limited referral and/or network system. For example, in Tacoma, Washington, the Greater Christ Temple Church has a child care program for low-income families and a multifaceted youth program that serves over two hundred at-risk youth per week at its Oasis of Hope Center. The First Baptist Church and the Peace Lutheran Church in Tacoma also have numerous programs for at-risk children and youth.

These churches are mentioned because most children and families of color have some type of social support system, including their ties to some type of church or religious organization, when they enter the child welfare system. The church has always been a protective factor in the African American community because of the high level of social support and services that it has provided since slavery. “The church has also provided families with the hope and courage they need to sustain hard times, whether due to limited financial resources or any other form of racially based prejudice and oppression” (Prater 2000, 102). The church has been shown to be a protective factor for African American children and has resulted in documented positive outcomes (Brown & Gary 1991; Hill-Lubin 1991; Zimmerman & Maron 1992; Haight 1998).

Best practice would dictate that child welfare professionals assess for social support whenever children of color and their families enter the child welfare system (see table 3.2 and figure 3.3). The church is a protective factor that can be utilized in a differential response system to keep children of color from entering the system and in permanency planning for the disproportionate number of children of color that have already entered the system.

It is imperative for professionals in the child welfare system to work collaboratively with American Indian Tribes to make sure that services for Indian children are culturally sensitive, as well as culturally appropriate. An example of this type of collaboration is the work that was done by the American Indian Tribes in Washington State and the Children’s Administration of the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. The end result of this work was the Washington State 2012 Indian Child Welfare (ICW) Case Review Tool, which is utilized to evaluate “compliance and quality of practice in meeting the: Federal Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA); Washington State Indian Child Welfare Act (WSICWA); Children’s Administration (CA) ICW policies; Washington State Tribal/State Agreement and Local Tribal/State agreements” (Federally Recognized Tribes of Washington State & Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, Children’s Administration 2012, 2). This evaluative tool is also used to measure the quality of practice, comprehensiveness of service delivery, and cultural competence of case management and other services for American Indian children and their families.

Native American children, youth, and families can receive a range of culturally appropriate services from the Circles of Care program. This federally funded grant program has been developed and implemented in many tribal and urban Indian communities in this country. This system of care is defined as a coordinated network of community based services and supports that are organized to meet the challenges of children and youth with many needs and their families. In a system of care model, families and youth work in partnership with public and private organizations to design mental health services and supports that are effective, that build on the strengths of individuals and that address each person’s cultural and linguistic needs.

(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010, 1–2)

TABLE 3.2 Social Network Grid

Source: E. M. Tracy and J. K. Whittaker. (1990) “The Social Network Map: Assessing Social Support in Clinical Practice.” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 71, 461–470. Permission to Reprint: Alliance for Children and Families.

The following are some of the tribal and urban Indian communities that have implemented Circles of Care: the American Indian Center of Chicago; the Indian Center, Lincoln, Nebraska; the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation; the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North Dakota; the Karuk Tribe of California; the Pueblo of San Felipe, New Mexico; and the Crow Creek Tribe of South Dakota. This culturally appropriate program would greatly benefit many of the Native American children who are disproportionately represented in child welfare programs across the country.

Another community service facility with varied programs is the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic in Seattle, Washington. This clinic provides services to a large number of children in the foster care system. It takes a proactive approach in its work with multicultural families to help them discover their voices and where they belong in the world. The clinic was started in 1970 and named in honor of Ms. Odessa Brown, an African American community activist who advocated for quality health care with dignity for children in the central area of Seattle. Ms. Brown and her young children lived in Chicago prior to relocating to the Seattle area. In Chicago she tried to get medical care at a hospital for her health problems but was turned away and denied care because of her race. The mission of the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic is to be “an enduring community partner with a dedication to promoting quality pediatric care, family advocacy, health collaboration, mentoring and education in a culturally relevant context” (Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic 2011, 1). Two noteworthy programs at the clinic are Reach Out and Read (ROR) and the Medical-Legal Partnership for Children (MLPC). ROR is a national program developed to increase children’s literacy skills; any child who is seen for a well visit at the clinic always leaves the clinic with a new book. Medical providers, social workers, and lawyers work together in the MLPC to address legal problems of patients and families. The program has a full-time attorney who provides free legal services to most families and a training component to teach medical providers and social workers about the legal and advocacy needs of patients and families. The Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic provides children and families with a high caliber of comprehensive medical, dental, and mental health services; mentoring; education; and family advocacy in a culturally relevant context.

It is a known fact that extended families in many cultures are ready and willing to be actively involved in making decisions about children who are a significant part of their lives. However, the formalized practice of family group decision making (FGDM) developed as a result of a need to find solutions to the problem of racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system. New Zealand’s Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act mandated the use of FGDM, known there as family group conferencing (FGC), many years ago to deal with institutional racism experienced by the disproportionate number of Maori children in the child welfare system and to facilitate better outcomes for these children (Connolly 2004).

FGDM was implemented in the United States in the early 1990s and is touted as a promising practice to address the pressing problems of disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system today. Sheets et al. (2009) found that when African American and Hispanic families in Texas participated in FGDM, there was an increase in family reunification, earlier exits from the child welfare system, and more reports of positive experiences by birth parents and extended family members with FGDM than with other child welfare practices. Findings from another study in Texas demonstrated that “32 percent of African American children whose families attended such a conference returned home compared to 14 percent whose families received traditional services” (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2007). FGDM is a practice that is culturally sensitive and congruent with the natural support system that has been prevalent in families of color for many generations.

Merker-Holguin, Nixon, and Burford (2003) analyzed international research on FGDM and reported that the practice provides child safety, it allows a greater percentage of children to stay with their extended family, it results in timely decisions and outcomes, it provides a higher degree of family support and thus improved family functioning, it encourages stability for children as a result of plans, and it protects other family members so family groups are willing to participate in meetings if provided the opportunity.

An exemplary multifamily group program is FAST (Families and Schools Together); this evidence- and theory-based program was developed by Dr. Lynn McDonald in 1988 in Madison, Wisconsin. The goals of FAST are to increase child well-being, enhance family functioning, prevent the target child from experiencing school failure, increase parental involvement in the child’s school, increase social capital, and reduce the stress that parents and children experience from the circumstances of their daily lives (Families and Schools Together n.d.). FAST builds protective factors into the child’s ecological system by enhancing the child’s relationships with other family members, with peers, and with other families, as well as the child’s relationships with the school and community.

Twelve to fifteen families participate in a series of eight weekly meetings that are usually held in the evening at a school in the community where the children and families reside. A team of parents and professionals provides activities for the family as a unit, parent and child, parents, peer groups, self-help groups, and the entire group of twelve to fifteen families, utilizing a “fun/play-based approach” (Families and Schools Together n.d., 1). Outcomes for families who have graduated from the eight-week program have been very high—e.g., an 80 percent graduation rate and 50 percent participation in parent-run multifamily meetings for two years after graduation. Parents and teachers reported vast improvements in the home and school functioning of at-risk children who participated in FAST for eight weeks. Children of all ages, cultures, and races can participate in FAST (Baby FAST, Pre-K FAST, Kids FAST, Middle School FAST, and Teen FAST. FAST is a most successful program in thirteen countries (Australia, Austria, Canada, England, Germany, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Russia, Scotland, Tajikistan, the United States (46 states), and Wales.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that best practice also includes providing services to children and families of color that are culturally relevant. Child welfare professionals must have cultural sensitivity, as well as some level of cultural competence, in their work with children and families of color.

CULTURAL SENSITIVITY AND CULTURAL COMPETENCY

It is imperative for all child welfare professionals to have sensitivity, knowledge, and skills in their work with children of color and their families, who continue to enter and remain in the child welfare system in disproportionate numbers. There is much diversity among the different children of color who are overrepresented in the child welfare system. Diversity is defined by De La Cancela, Jenkins, and Chin (1993) as follows:

Diversity is the valorization of alternate lifestyles, biculturality, human differences, and uniqueness in individual and group life. Diversity promotes an informed connectedness to one’s reference group, self-knowledge, empowering contact with those different from oneself, and an appreciation for the commonalities of our human condition. Diversity also requires an authentic exploration of the client’s and practitioner’s personal and reference group history. This exploration empowers the therapeutic dyad by providing a meaningful context for understanding present realities, problems of daily living, and available solutions. (6)

There are primary and secondary characteristics that distinguish diversity. Primary characteristics—for example, gender, age, size, and ethnicity—are often visible but can be quite different for varied groups; however, secondary characteristics—for example, socioeconomic status, marital/family status, religion, and education—tend to be invisible and can change (Purnell 2002). Child welfare workers, supervisors, administrators, researchers, and policy makers need to have cultural sensitivity, cultural awareness and self-awareness, and some degree of cultural competency in all facets of work with a diverse group of children of color and their families. There are numerous definitions of cultural competency; however, the following definition seems most appropriate in this discourse regarding racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system:

Cultural competence comprises behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together on a continuum that will ensure that a system, agency, program, or individual can function effectively and appropriately in diverse cultural interaction and settings. It ensures an understanding, appreciation, and respect of cultural differences and similarities within, among, and between groups. Cultural competency is a goal that a system, agency, program or individual continually aspires to achieve.

(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2003, 6–7)

One does not attend a conference, workshop, and/or training session and declare herself or himself culturally competent. Cultural competency is a process that takes commitment and work throughout one’s life span. No one is expected to know everything there is to know about the many diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural groups that exist in this country today; however, it is crucial to have some level of cultural knowledge, awareness, and competency in order to work effectively with children of color and their families in the context of their culture. Culture is the beliefs, values, and life lessons passed from one generation to another, including language, religion, modes of thinking, and ways of developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships. It is a strength that empowers children and enhances family functioning. It is also a key factor in child welfare practice today.

The child welfare professional’s level of cultural competency is significant because it will impact his or her relationships with clients—i.e., children, birth parents, and extended family—and will determine whether or not the professional is able to identify and provide services, interventions, and so on that are culturally relevant to diverse children and families. It is incumbent upon child welfare supervisors and administrators to monitor and evaluate the cultural competence of child welfare workers and other staff that are providing services to children of color and their families. This evaluation should be closely tied to annual performance evaluations for caseworkers and other staff.

According to Cross et al. (1989), cultural competence can be viewed as a developmental process for individuals as well as for organizations/agencies. During this evolving process individuals and organizations are at varied levels of awareness, knowledge, and skills along the Cultural Competency Continuum (see table 3.3). The continuum ranges from cultural proficiency to cultural destructiveness. The six stages along the continuum include (1) cultural destructiveness; (2) cultural incapacity; (3) cultural blindness; (4) cultural pre-competence; (5) cultural competency; and (6) cultural proficiency. An individual or organization/agency should not view the continuum in a linear matter. Individuals or organizations/agencies should always work to increase their level of cultural competence (see table 3.3).

TABLE 3.3 Cultural Competency Continuum

Source: Cross, T. L. (1989). Cultural competency continuum. Portland, OR: National Indian Child Welfare Association. Reprinted by permission of Terry L. Cross, MSW, Executive Director, National Indian Child Welfare Association.

In working with diverse children and families it is also important for child welfare professionals to have self-awareness. Self-awareness means internal and external knowledge of one’s personality traits, attitudes, emotions, biases, preconceived notions, prejudices, history, values, and so on. It is imperative in any type of training for cultural competency to strongly encourage participants to develop self-awareness. Lack of self-awareness will hamper one’s efforts to gain the knowledge and skills essential for working effectively with the disproportionate number of children and families of color in the child welfare system. Self-awareness is a powerful connector to one’s present as well as to one’s past. With a sense of self-awareness child welfare administrators, practitioners, policy makers, and researchers are able to develop and implement plans to work proactively to eliminate disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system (see the following Self-Assessment Tool).

SOCIAL WORK CULTURAL COMPETENCIES SELF-ASSESSMENT TOOL

This instrument measures your level of cultural competency. Rate yourself on your level of competency on a scale of 1–4: 1 = Definitely; 2 = Likely; 3 = Not very likely; and 4 = Unlikely. Circle the appropriate number.

CULTURAL AWARENESS

1. I am aware of my life experiences as a person related to a culture (e.g., family heritage, household and community events, beliefs, and practices).

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2. I have contact with individuals, families, and groups of other cultures and ethnicities.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

3. I am aware of positive and negative experiences with persons and events of other cultures and ethnicities.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

4. I know how to evaluate the cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of my racism, prejudice, and discrimination.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5. I have assessed my involvement with cultural and ethnic people of color in childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and adulthood.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6. I have done or plan to do academic course work, fieldwork, and research on culturally diverse clients and groups.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

7. I have or plan to have professional employment experiences with culturally diverse clients and programs.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

8. I have assessed or plan to assess my academic and professional work experiences with cultural diversity and culturally diverse clients.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION

9. I understand the following terms: ethnic minority, multiculturalism, diversity, people of color.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

10. I have a knowledge of demographic profiles of some culturally diverse populations.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

11. I have developed a critical thinking perspective on cultural diversity.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

12. I understand the history of oppression and of multicultural social groups.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

13. I know about the strengths of men, women, and children of color.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

14. I know about culturally diverse values.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

15. I know how to apply systems theory and psychosocial theory to multicultural social work.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

16. I have knowledge of theories of ethnicity, culture, minority identity, and social class.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

17. I know how to draw on a range of social science theory from cross-cultural psychology, multicultural counseling and therapy, and anthropology.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

18. I understand how to overcome the resistance and lower the communication barriers of a multicultural client.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

19. I know how to obtain personal and family background information and determine the extent of his or her ethnic/community sense of identity.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

20. I understand the concepts of ethnic community and practice relationship protocols with a multicultural client.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

21. I use professional self-disclosure with a multicultural client.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

22. I have a positive and open communication style and use open-ended listening responses.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

23. I know how to obtain problem information, facilitate problem area disclosure, and promote problem understanding.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

24. I view a problem as an unsatisfied want or an unfulfilled need.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

25. I know how to explain problems on micro, meso, and macro levels.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

26. I know how to explain problem themes (racism, prejudice, discrimination) and expressions (oppression, powerless, stereotyping, acculturation, and exploitation).

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

27. I know how to find out problem details.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

28. I know how to assess socioenvironmental stressors, psychoindividual reactions, and cultural strengths.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

29. I know how to assess the biological, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of a multicultural client.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

30. I know how to establish joint goals and agreements with the client that are culturally acceptable.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

31. I know how to formulate micro, meso, and macro intervention strategies that address the cultural and special needs of the client.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

32. I know how to initiate termination in a way that links the client to an ethnic community resource, reviews significant progress and growth, evaluates goal outcomes, and establishes a follow-up strategy.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

33. I know how to design a service delivery and agency linkage and culturally effective social service programs in ethnic communities.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

34. I have been involved in services that have been accessible to the ethnic community.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

35. I have participated in delivering pragmatic and positive services that meet the tangible needs of the ethnic community.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

36. I have observed the effectiveness of bilingual/bicultural workers who reflect the ethnic composition of the clientele.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

37. I have participated in community outreach education and prevention that establish visible services, culturally sensitive programs, and credible staff.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

38. I have been involved in a service linkage network to related social agencies that ensures rapid referral and program collaboration.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

39. I have participated as a staff member in fostering a conducive agency setting with a friendly and helpful atmosphere.

| Definitely |

Likely |

Not very likely |

Unlikely |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

40. I am involved or plan to be involved with cultural skill development research in areas related to cultural empathy, clinical alliance, goal-obtaining styles, achieving styles, practice skills, and outcome research.

| Definitely |

Likely |