OTHERS, APART FROM THE LANDSHIP COMMITTEE, were interesting themselves in turning warfare from a physical to a mechanical business. Some of the brightest military minds had in the beginning been relegated to the duties of chauffeuring the great because they had made the mistake, if such it was, of quitting the Service before time. By this means many of them managed to get back into harness again.

Toby Rawlinson, General Sir Henry’s younger brother, had a task of his own. When ordered by the General to provide trench-mortars with which to make some reply to the Germans he scoured French military museums, rescued a number of pieces dating from the Crimea or earlier, recruited Belgian refugee labour to make shells for them and finally brought several batteries of ‘Toby Mortars’ – their official name – into action at Aubers Ridge on 9 May. There remained Christopher d’Arcy Bloomfield Saltern Baker-Carr, late Rifle Brigade but now a civilian in a uniform bought off the peg from Burberrys and lacking all insignia and badges. Though several years retired he was still only 36 and lusted after a fighting command. Baker-Carr knew more than most about modern weapons. He had seen at Omdurman what a belt-fed machine-gun could do to unarmoured masses. He had been an instructor at the Small Arms School, Hythe, where the Regular Army had been trained to its 1914 excellence. In South Africa he had got into ‘terrible trouble’ because when bidden to make a barbed-wire entanglement he had quite deliberately made it more difficult to surmount by being irregularly spaced and loosely stretched. His next senior officer, in addition to abusing him roundly, made him take it down and reassemble it properly; tightly drawn and dressed by the left. Baker-Carr had a fine contempt for the military mind, based wholly upon experience.

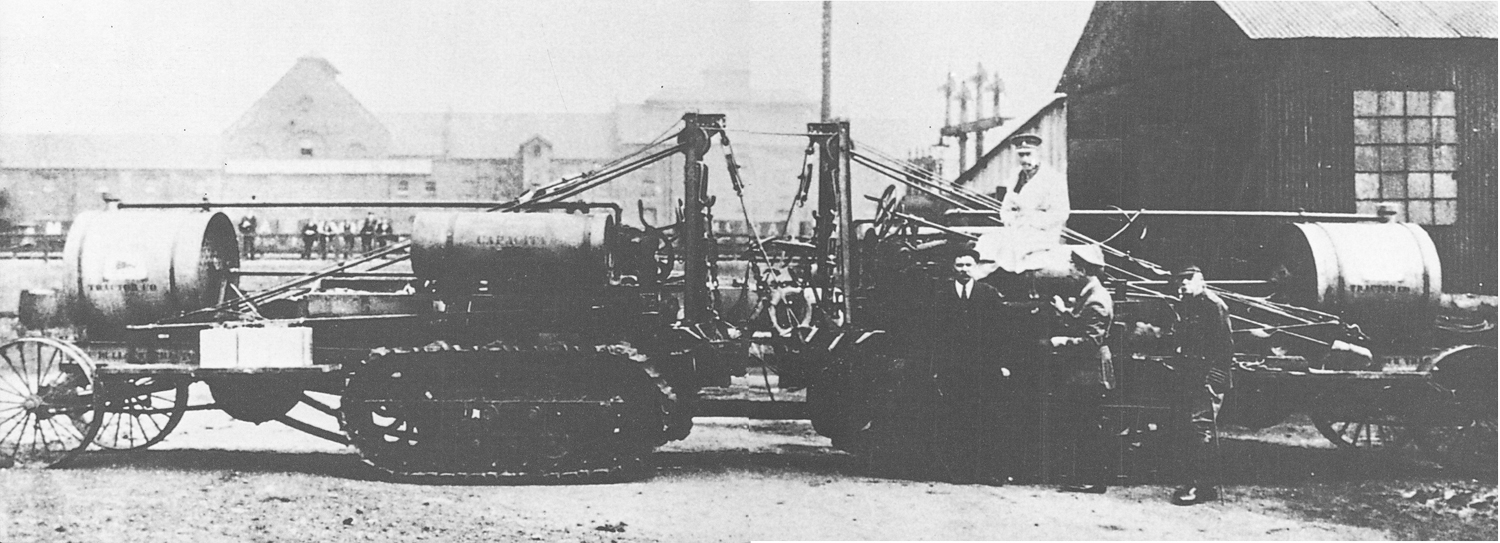

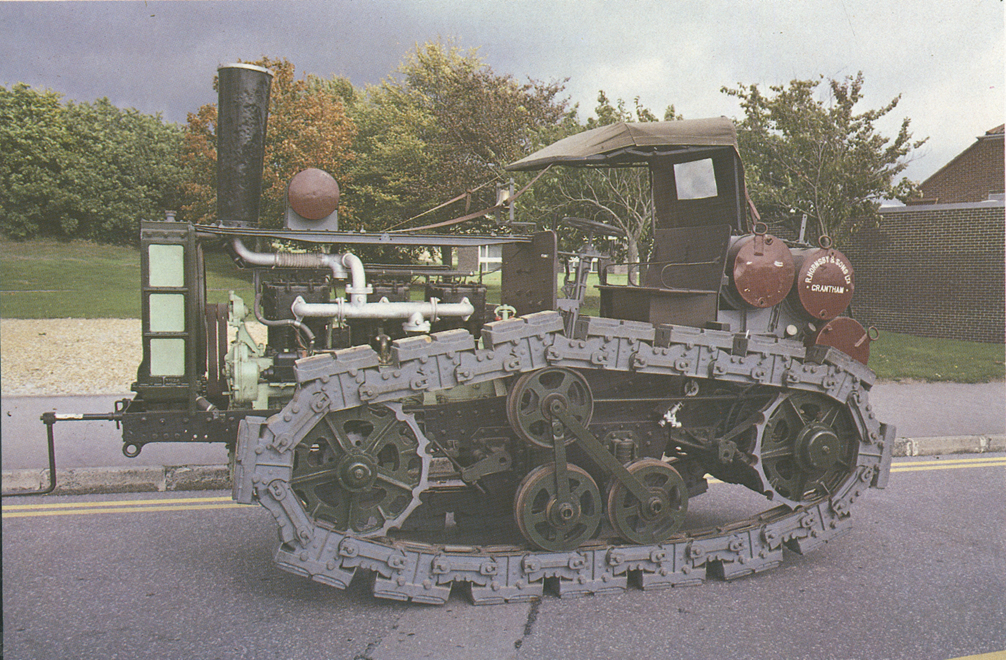

The Hornsby chain-tracked tractor of 1909.

The trouble with the military mind was that many of those who best exemplified it were in every other respect admirable men. Such a one was George Montague Harper, late of the Royal Engineers, later Lieutenant-General Sir George, but in the Spring of 1915, plain Colonel, GS. Though only 50 his hair had become prematurely white, contrasting strongly with his black moustache. There was something symbolic about this for in his world everything was of either one or the other of these colours. He had been known as ‘Uncle’ ever since his days as an Instructor at the Staff College under Henry Wilson, upon whose translation to the War Office in 1911 as Director of Military Operations ‘Uncle’ had followed as his acolyte. Everything covered by a Staff College school solution was white; everything else black. It was impossible not to like him. No unpleasant man has ever been called ‘Uncle’ in the Army. It is a patent of merit.

Major-General Thomson Capper, GOC 7 Division and the rock upon which the Germans had broken at First Ypres, was the complete fighting leader and he had no interest in anything but beating the Germans in the field. It so happened that when Lord Roberts died at St Omer, a few days after the Ypres battle had petered out, Baker-Carr went to his funeral. There he met Capper who invited him to watch a parade by one of his Brigades and afterwards to luncheon. The parade showed how Capper’s Division had fought. A small field easily held all that was left of four strong battalions; one of them mustered a solitary officer and about fifty men; the total came to less than 300 all ranks. The War Establishment of an infantry brigade was just over 4,000. During the meal Capper spoke of re-building. ‘You were an Instructor at Hythe, Baker-Carr. Why don’t you come and do a real job of work?’ Baker-Carr jumped at the chance. ‘Come to my Division and train my machine-gunners for me. There isn’t a single one left.’

GHQ consent being needed, Baker-Carr visited Colonel Lambton, Sir John French’s Military Secretary. They agreed that Baker-Carr should train machine-gunners, not merely those of Capper’s Division but of the whole British Army in France. There were few enough of them. He was bidden to see ‘Uncle’ Harper and fix up details. Baker-Carr walked into ‘Uncle’s’ office ‘and touched my cap. “Colonel Lambton told me to see you about training some machine-gunners for the Divisions, Sir,” I began. “Yes,” said “Uncle”, “he telephoned me about it. Why don’t you get on with it?” “I want some sort of authority before I can start, sir.” “All right,” replied “Uncle,” “you’ve got it. Now get on with it.” “But …,” I began again. “Look here. Baker,” said “Uncle”, “are you running this show or am I? Go away and do what you like, but don’t bother me. I’m busy.”’ Thus began the Machine Gun School; from it descended the Machine Gun Corps and from that the Tank Corps.

The faites et gestes of Baker-Carr and his Machine Gun School fall outside this narrative but they are not irrelevant. One of the most frequent visitors was the ‘Eyewitness’, Colonel Swinton. Another was General Sir Charles Monro who had been Commandant at Hythe when Baker-Carr had been an Instructor; to him more than to any other man the Army owed its 1914 skill at arms. Towards the end of 1915 the General announced that he would like to see a range practice. You will remember, if indeed you needed to be told, that a trained soldier could get off more than thirty aimed shots during the ‘mad minute’. The prize on this occasion was won by a sergeant in a Guards battalion; he managed to fire precisely twelve rounds. To such depths had skill with the rifle fallen in a single year.

Baker-Carr had much to say to Swinton about this and many other things. The two men between them mustered an enormous amount of campaigning experience and the talk naturally enough turned to machine-guns, their use and how to circumvent them. Swinton told of the fate of Hankey’s Boxing Day paper at the hands of the War Office department to which he had sent it. The note pinned to it on its return read ‘If the writer of this paper would descend from the realms of fancy to the regions of hard fact a great deal of valuable time and labour would be saved’. It seems a reasonable assumption that Swinton had not included the name of the author.

Swinton and Baker-Carr talked caterpillars and armour for many hours. Both railed against the closed minds of the hierarchy in Whitehall and at St Omer where GHQ still resided. The case for serious experiment seemed unanswerable but nothing appeared to be happening. Nothing either man could do would make any difference.

All seemed hopeless until the month of July, 1915, arrived. Mr Asquith invited Swinton to become Secretary to the War Committee and in that capacity he learned of the existence of the struggling Landship Committee. Stern was summoned before him. Their initial conversation has gone down in history. ‘Lieutenant Stern, this is the most extraordinary thing that I have ever seen. The Director of Naval Construction appears to be making land battleships for the Army who have never asked for them, and are doing nothing to help. You have nothing but naval ratings doing all your work. What on earth are you? Are you a mechanic or a chauffeur?’ ‘A banker’. Stern replied. ‘This’, said he, ‘makes it still more mysterious.’

The two men got on from the start. At last Stern had the opportunity of telling somebody with authority exactly what his Committee had been up to and he took it. Henceforth the progenitors of the tank were joined together in something like lawful wedlock.

Much work had been done during the last few months. Mr Churchill, before the Dardanelles had swallowed him up, had ordered one dozen Pedrail machines and half a dozen 16-foot Bigwheel Landships. The Pedrail, designed by Colonel Crompton, the grand old man of civil, mechanical and electrical engineering, was a larger version of the Diplock machine.

Rookes Evelyn Bell Crompton deserves more than a passing mention. Apart from being the senior mechanical engineer in active practice, he was the connecting-file between the armies of Wellington and of Haig. In 1855, at the age of 10, he had accompanied his mother’s cousin Captain William Houston Stewart, RN, to the Crimea where the Commander-in-Chief was Lord Raglan who had served throughout the Peninsula as the Duke’s Military Secretary. Stewart was Captain of HMS Dragon and in order to find a berth for his young kinsman he had had him regularly enrolled as a Naval Cadet. On the strength of a visit to the trenches to see his elder brother Crompton qualified and he was duly awarded the Crimean medal with the Sebastopol clasp. Thus decorated, he went on to Harrow. During school holidays he built himself a full-sized steam-driven road locomotive. Very possibly this owed something to his war experience, for the Crimea had more in common with the early stages of the Kaiser’s War than is generally realized. After the charges of the Heavy and Light Brigades were over serious men had produced machines that might have hastened mechanization of the Army had the war not come to an abrupt conclusion. Steam engines running on rails were beginning to bring order into the chaos that existed between port and army, and steam tractors with footed wheels were of greater sophistication than anything yet seen. Had the war continued for another year the Crimean tank might have put in an appearance. It was well within the capacity of Brunei’s generation.

After leaving Harrow Crompton had been commissioned into the Rifle Brigade and served with them in India from 1864 to 1868. There he had been given a grant of £500 for furnishing the Viceroy, Lord Minto, with a serviceable steam road-train with which to replace his elephants. In 1875 he had sent in his papers and turned his talents towards electricity. The Mansion House, the new Law Courts and the Ring Theatre in Vienna all had their electric lighting systems designed and installed by the Crompton Company. So also did a good part of London. Lord Roberts had summoned him to South Africa where he raised and commanded a corps of electrical engineers whose efficiency at maintaining communications became a byword. That war over he left the Army again, with the entirely genuine rank of Lieut-Colonel, to become engineering member of the Roads Board whose business was to produce highways fit for motor traffic. The man who had seen the Crimea lived to see Hitler’s tanks preparing to carve up a later BEF. He died in 1940.

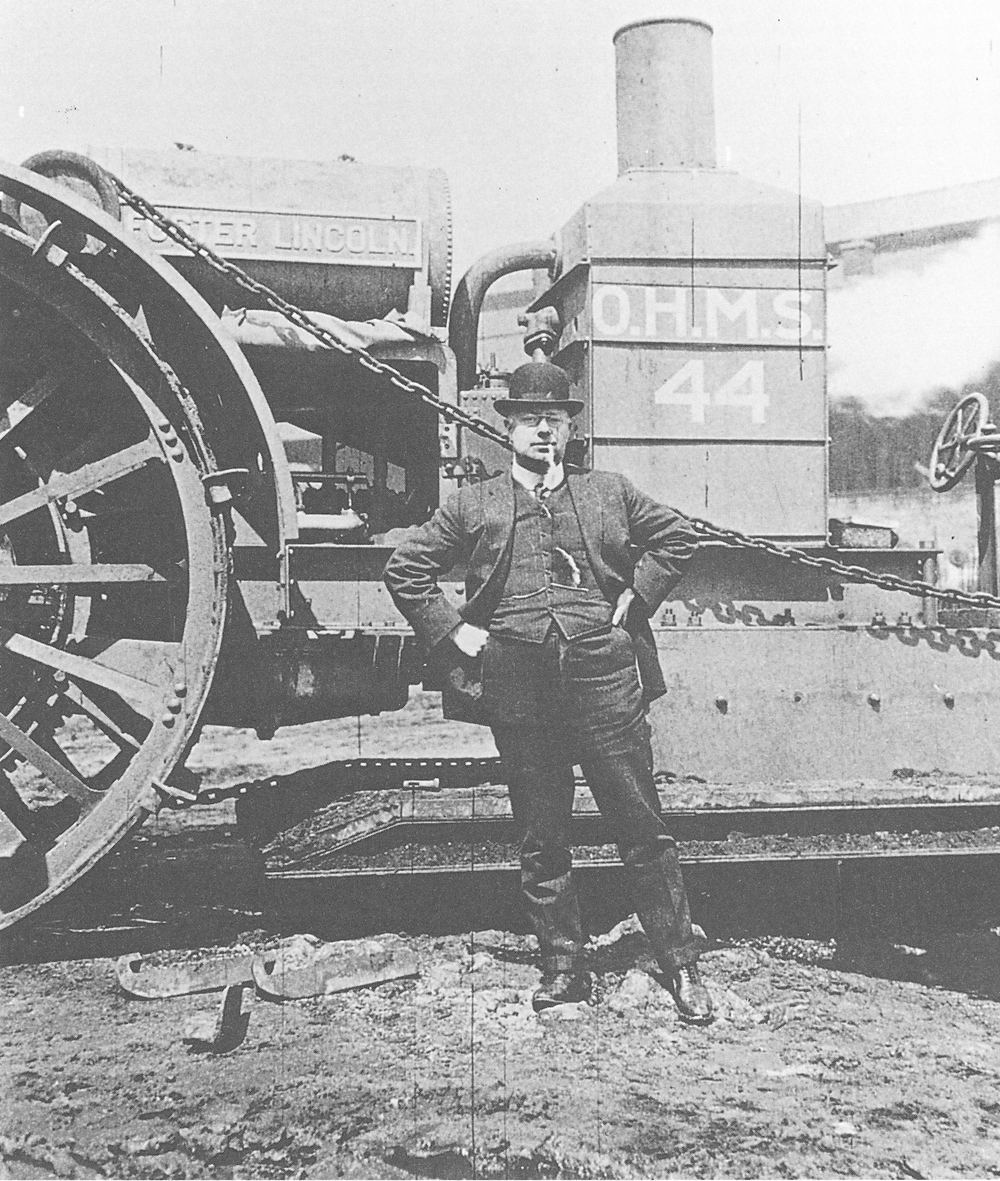

The design of the Pedrail was his; construction of the Big Wheeler, as it was called, was entrusted to Mr Tritton of Foster & Co, Engineers and Boilermakers, of Wellington Foundry, Lincoln.

The Pedrail machine, called by Crompton the ‘Articulateur’, would, had it been possible to take enough time over it, have been the first articulated vehicle. It was intended not as a tank but as a carrier for fifty men, ‘standing in two ranks at each side’, and it was to be protected by armour about ¼″ thick. Originally it was designed for a length of 40 feet by a beam of 13 and it soon became obvious that it could never go round a corner. Crompton therefore cut it in half, the two parts being connected by ‘a special form of joint’. Motive power was to come from a pair of Rolls Royce engines. Probably fortunately, it soon became apparent that the Pedrail form of caterpillar was nowhere near up to the demands made upon it and Articulateur was scrapped before it had got very far. Parts of it were sold off to the Trench Warfare Department for conversion into a flamethrower.

Tritton dealt with all these things in a long letter to Crompton dated 5 June, 1915. ‘It would take men of very strong nerves to fight such a machine while being attacked by an enemy’ was not an over-statement. He had, however, another suggestion. ‘An electrically driven wagon or fort could be made, driven by a dynamo attached to an independent tractor, connected by a cable unwound from a drum in the wagon and carrying a length of up to a mile. The well-known advantages of a series-wound motor enable enormous torque to be applied by the road wheels, thereby enabling the engine to come out of shell holes in which a petrol drive tractor would be held fast’. This was undoubtedly true; equally true was the fact that severance of the cable would halt the whole thing. It was not followed up. It appears strange now that practical and highly trained men should have set so much store by electric engines. Unfortunately they did not vanish for good with Tritton’s proposed machine.

In May Mr Churchill left the Admiralty; he was the firmest and possibly the only friend to the Landships. Fortunately his successor, Arthur Balfour, asked him to stay on unofficially in order to watch over the activities of his Committee.

Members of the Committee were kept up to the collar. Lieut Wilson, for example, spent 12 April at Derby where Rolls Royce were working on chassis plans for the Big Wheeler. Next day he was at Lincoln with Tritton. Fosters needed armour plate from Beardmores and permission to buy six 105 hp Daimler engines from the makers. Wilson saw to this. Hetherington and Stern had been to Paris a few days earlier to interview a M. Derocle who claimed to know all about armour. Syme, the expert on this subject, arranged for a test to be carried out at Woolwich on 21 April. M. Derocle was there with ‘a patent material and certain other substances’. Two pieces of plate and ‘1½ inches of Derocle jelly’ were made into a sandwich and set up. A Mk VI bullet from a Lee-Metford – obsolete these many years – achieved ‘complete penetration and a bad tear in the back plate’. The Derocle jelly went the same way as the Pedrail, the Articulateur, the Lemon Wheel and the Elephant’s Feet, early travellers down a road to be littered with disappointments. Syme turned his mind to more conventional forms of armour. The Landships Committee by early June had little to show for its hard work.

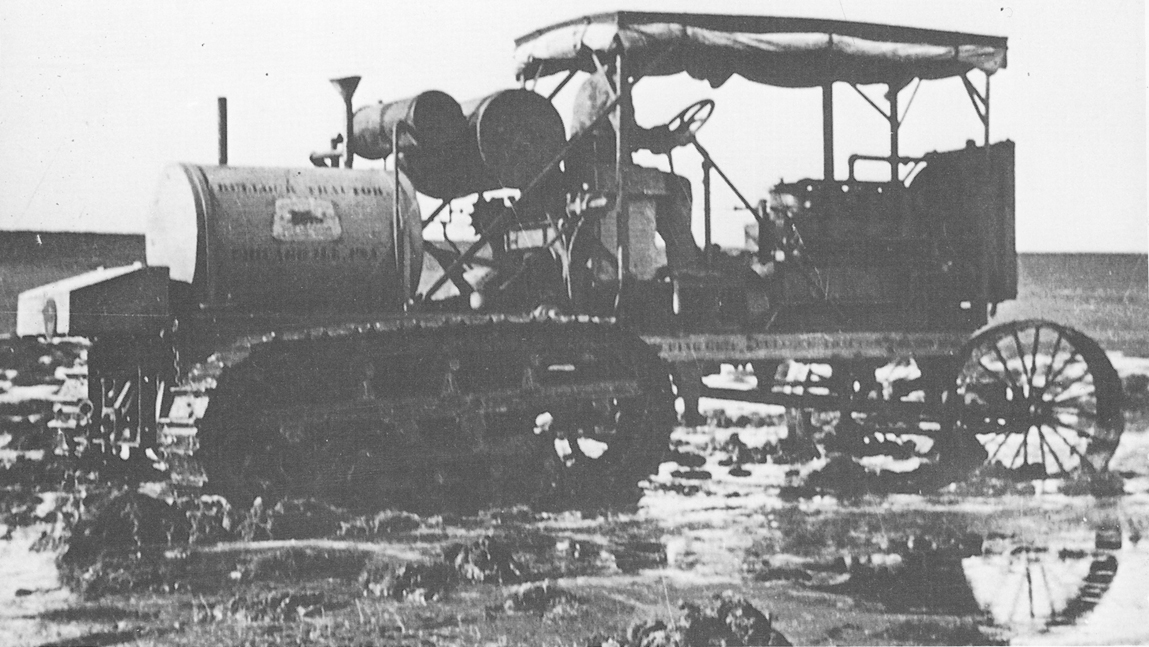

Important things were, nevertheless, beginning to happen. Everybody agreed that caterpillar tracks would be the only means of carrying heavy weights over bad ground. The difficulty was that the only two systems known, the Holt and the Killen-Strait, were too short for the purposes of the Committee. Sueter says that Commander Briggs happened to go into ‘one of those foreign book-shops off Leicester Square’ and came out with a copy of the Scientific American for 18 February, 1911, which contained details of a much longer machine designed for moving heavy loads of an agricultural kind over bad surfaces. This had to be investigated. Mr Field, one of Crompton’s men, was hastily commissioned as Lieutenant RNVR and packed off to Chicago with orders to examine and report upon the Bullock Creeping Grip. His report was enthusiastic and two Giant machines using the system were ordered.

Crompton, meanwhile, wanted more information about the nature of the obstacles that any machine of this kind might have to cross. With Stern and Hetherington for company he set off for France. Once the party got to GHQ at St Omer, however, they received a dusty reception. Nobody knew anything about them and a Staff Officer was inexcuseably rude to the old Colonel. They came home no better informed about the size and quality of German trenches than before.

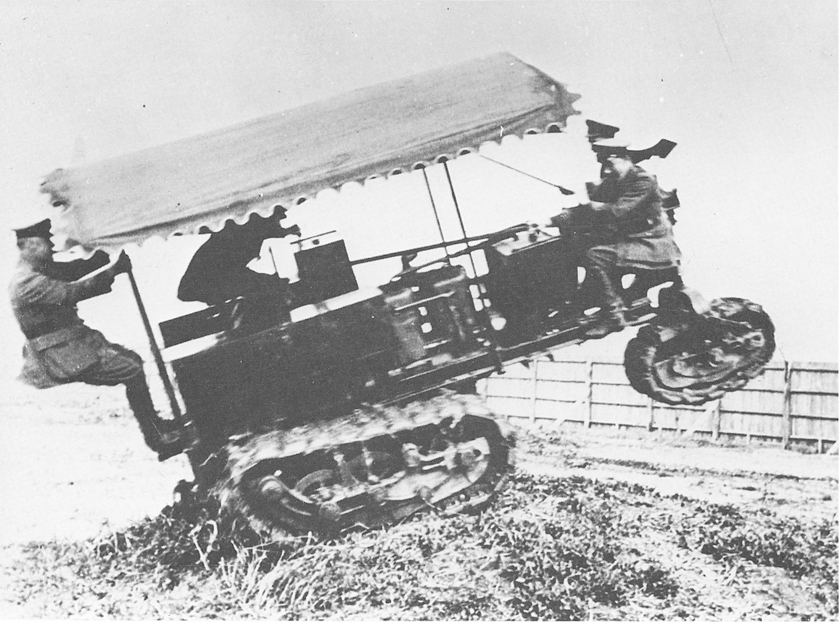

The old gentleman was undeterred. As soon as he learned that a Creeping Grip machine was known to be at work in the marshes at Greenhithe he arranged for an inspection. The Greenhithe Machine, as it came to be called, was really a half-track, with a pair of iron wheels in the front by which it was steered. Apart from a canopy over the driver’s head there was no sort of protection from weather or anything else. Unlike the Hornsby this machine had no suspension, a circumstance which at least reduced the likelihood of sea-sickness. Crompton made Hetherington drive it through the marsh and was pleased by its performance. It was not yet sufficiently convincing for him as he wanted to try two machines in tandem and this appeared to be the only one in the country. Final judgment would have to await the arrival of Field’s purchase.

The Landship Committee was not a heavy burden on the taxpayer. The Office of Works invited it to occupy a room in Whitehall. It later admitted the room to be small, stuffy and at the top of many flights of stairs. Stern, accustomed to far better things, took one look at it and made some enquiries on his own. Lord Kitchener, in the words of his May statement on the war, had decided that ‘the only course open was impressment of every available motor vehicle which was in running order’ and he had collared some 8,000 lorries, about a quarter of the total commercial vehicles in the Kingdom at August, 1914. The Commercial Motor Users Association was glad to offer a weekly tenancy of Room 59 in its office at 83 Pall Mall for £2 a week. Stern took it and moved in at once. The Office of Works was furious and one of its understrappers wrote a minute complaining that a temporary officer, ‘a certain Lieutenant Stern’, had had the temerity to send in a bill for the rent. The matter smoothed itself down in time. The poky little room at the top of all those stairs was given to an Admiral. For a time Stern paid the rent himself. He would hardly have noticed £2 a week. It was, however, his introduction to Governmental ways of doing things and these ways he soon came to hate and despise. They were not businesslike and, to a merchant banker, business was everything.

The Chicago-built Bullock Creeping Grip tractor.

On 8 June the Committee, including Mr Bussell of the Admiralty and Cmdr Boothby, OC Armoured Car Section, met in Mr Churchill’s room at the Official Residence in Whitehall. The big wheel was given its quietus; what mattered was that two Giant tractors from America with the Creeping Grip were at sea on board s.s. Lapland. They should arrive in a fortnight at worst. Approval was given to the purchase of one Killen-Strait tractor which looked promising. On the 21st Crompton reported that the Bullocks had arrived and were at the factory of McEwan Pratt & Co, Burton on Trent. Since there was no place for trying them out Wilson leased a field at Sinai Park from Mr Loverock for a year; the two-guineas rent came out of his own pocket.

The Giants represented most of the Committee’s assets, for the only others were the Killen-Strait tractor at the Clement Talbot works in Barlby Road and two of the builders’-skip-on-a-track machines. Wilson took over the Giant testing on his field with some help from Colonel Crompton, whose small, neat figure appears in a number of photographs bent over the mechanism. The Giants were coupled back to back and set to work, one pulling whilst the other idled; then back again in reverse order. Wilson learnt little from this, nor had he expected to. His interests were in the track and the transmission, neither of which had been designed for his purposes. The track came up to Crompton’s expectations, for Sinai Park was better holding ground than Greenhithe Marshes. The transmission was quite another matter. It served for an agricultural tractor but was clearly not going to be man enough for a heavy-bodied vehicle with the much bigger Daimler engine.

Walter Gordon Wilson, born in 1874, was the same age as Mr Churchill. He had remained only a very short time in the Navy and at 20 had moved to King’s College, Cambridge, where he gained a First in mechanical engineering. Through Lord Braye he had become acquainted with Percy Pilcher, then a lecturer in naval architecture and a pioneer of flying. The two men formed a little company to build what might have been the first internal combustion engine to power a flying machine; when Pilcher was killed by a gliding accident in 1899 Wilson seemed to lose interest in flight and turned to road transport. In 1904 he designed and built a car which he called the Wilson-Pilcher. It still stands, under a glass case, in the Tank Museum. After that he moved to Armstrong-Whitworth where he designed their first car and between 1908 and 1914 he was with J & E Hall at Dartford, designing the Halford lorry. Though under no compulsion but that of conscience he threw up well-paid work on the outbreak of war to come back to the Navy, where he naturally gravitated to the Armoured Cars. His specialité was the gear-box; probably no living man knew as much as Wilson about this interesting subject. He is said to have been a prickly man who did not suffer fools or those who did not understand mechanical engineering. ‘Genius’ is a word of which one should fight shy; yet it is hard to think of another for Walter Gordon Wilson. Some of his later designs are still in use with tanks of the present day.

According to his evidence given to the Royal Commission on Awards to Invesntors in 1919 Wilson first met Stern on 15 July, 1915. Stern complained to him that the Committee seemed to be getting nowhere and asked whether Wilson would prefer to work with Colonel Crompton or with Mr Tritton. Wilson replied that if Tritton and he were put on the job ‘we would soon produce a machine that could do something’.

Wilson was a dedicated engineer, by no means the clubbable kind of man like Bertie Stern. He and Tritton spoke the same language and, as their correspondence shows, they liked each other. Together they did great things, for every British tank used during the Kaiser’s War was built to their designs. D’Eyncourt supplied ideas; Stern was, in the jargon of the day, ‘the man of push and go’. There was need of all of them.

It has to be realized that Fosters was a commercial concern and, war or no war, was in business for profit. When Tritton had taken over conduct of its affairs in 1905 the Company, founded in 1856, was in low water. Only just before the war came had he pulled it round to the point when it was beginning to show a decent return. Whatever happened the shareholders expected their half-yearly dividends and the workmen expected to be paid on Fridays. No firm particularly wanted work on experimental machines; the constant changes in design were irksome, the finding of raw materials difficult since they were at the end of the queue and the money available for such things was not plentiful. It says much for Fosters’ patriotism that they took on the job at all. Tritton in due time was to receive his knighthood but no great profits were made. The Company, indeed, made the Government a free gift of its royalties from the use of the Foster-Daimler engine, for which it held the patents; Tritton put this at about £115,000. In 1915 he was just 40 and with his bald-head, pince-nez and expression of general benevolence could never have been regarded as a hard-faced man who looked as if he had done well out of the war.

By mid-summer 1915 matters were not going well. On 29 June the Admiralty had invited the War Office to interest itself in landships; the invitation was accepted but with some economy of enthusiasm. To the Army this was still a silly, time-wasting business, but if it had to be kept going the War Office ought to be informed about what was going on. Stern, in a moment of unusual gloom, admitted that he and the others came near to abandoning the whole project as hopeless since every technical expert on traction had assured him that the problems were beyond solution.

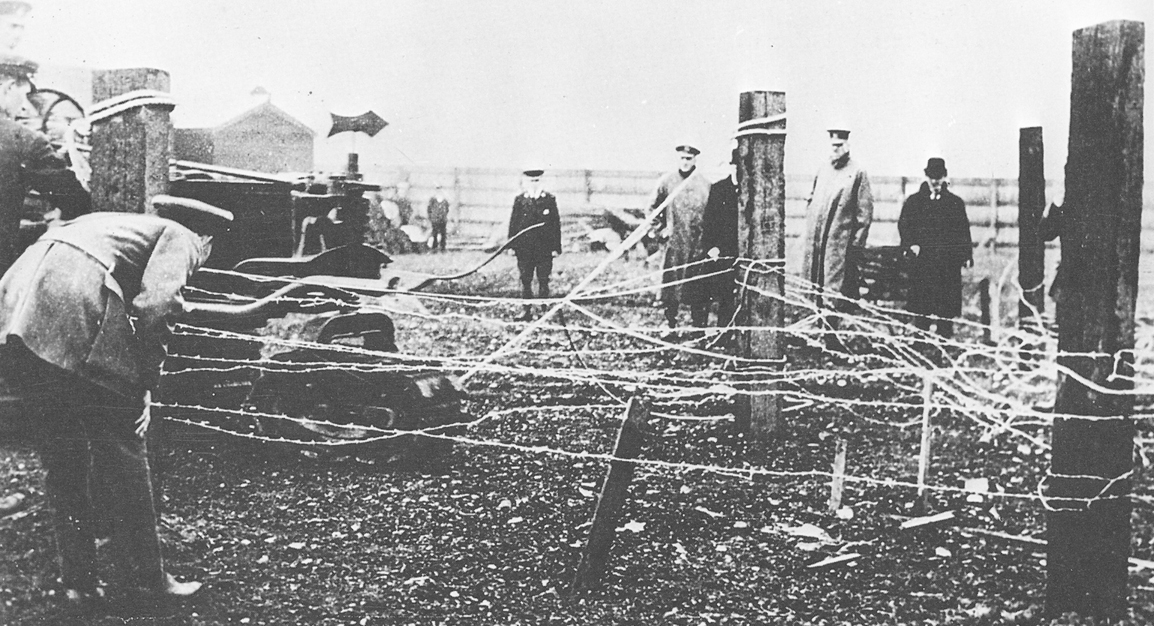

In order to keep the flickering flame alive he staged a demonstration at Wembley Stadium on 30 June, the day after the War Office had come in. There was not a lot to show. The main attraction was an exhibition of wire-cutting by one of the Committee’s few assets, the American made Killen-Strait tractor. It was an unmilitary looking machine, completely open and propelled by two small sets of caterpillars aft and an even smaller one forward. The driver sat high up, steering with a wheel. When fitted out with Navy wire-cutters the Killen-Strait showed itself able to tear its way through a barbed wire entanglement of a not very formidable kind. Amongst those present were Mr Churchill, Mr Lloyd George, now Minister of Munitions, and a Mr Wilfrid Stokes who had invented a trench-mortar of simple but effective design. Stern had been greatly taken by it and did not affect surprise when Stokes told him of the impossibility he had experienced in getting the War Office to show interest in his gun. Stern took him straight to Mr Lloyd George who watched the inventor put three shells into the air before the first one had hit the ground. To his question about how long manufacture of the mortar would take Stokes gave a proper East Anglian answer. ‘It depends whether you or I try to make them’. The Minister, suitably impressed, ordered a thousand of them at once. Even though the Killen-Strait achieved little else it earned its keep by being the indirect means of getting the Army a weapon second only to the machine-gun in value.

Though the Killen-Strait performance was nothing to excite anybody over much it did furnish evidence that the Landship Committee had possibilities, however remote at the time. The Admiralty, presumably at the instance of Mr Churchill, agreed that Squadron 20 RNAS should be relieved of all other duties and placed at the Committee’s disposal. This was a wise decision for it gave the pioneers all the man-power needed to continue with its work. The association was to last throughout the war, despite occasional attempts at breaking it; by November, 1918, Squadron 20, then of infantry battalion strength, worked on both sides of the Channel at the testing and delivery of every tank used by the BEF.

Better things than the Killen-Strait were coming along. Once it had shown off its paces it was furnished with rude armour and promptly set aside. It ended its days towing aircraft around the RNAS base at Barrow-in-Furness. Squadron 20 was moved to Burton-on-Trent under command of Hetherington there to await the next experiment.

The Giant tractors had yielded up all their technical data to Wilson and he was ready to use his knowledge on something more practical. Tritton had been working on his own and had built a trench-crossing machine of some ingenuity; it would have done well over drainage ditches but it was not a weapon of war. In fact it was one of the Bacon tractors with 8-foot wheels pushing an integrally built sledge mounted on two pairs of small wheels. Colonel Crompton, whose vast and expensive designs were becoming an embarrassment, left on termination of his 6 months contract early in August.

At the end of July the Committee asked Tritton and Wilson to make a machine which would incorporate the Bullock track, the Daimler 105 hp engine as used on Bacon’s tractors and an armoured body. The planned weight was about 18 tons and the machine must be able to cross a trench four feet wide. Like the Giants it would be steered by wheels but this time they should work from behind.

The designers established themselves in the White Hart at Lincoln. This was a sensible move, for difficulties were many and comfortable quarters needed. Some of the less technical were removed by Swinton who persuaded the Prime Minister to call an inter-departmental conference on 28 August. D’Eyncourt wrote to Stern on the following day that ‘the conference has distinctly cleared the air and put the whole thing on a sounder footing. I’m glad you had a good talk with Swinton; you seem to have arranged it very well, and I hope now we shall be able to go on steadily without more tiresome interruptions.’ Again he emphasized the need for utmost secrecy. This Stern effected by telling all enquirers that things were going very badly indeed and they were probably all about to lose their jobs.

For the time being all those concerned with producing a prototype caterpillar trench-crosser worked very happily together and there was a family atmosphere about the White Hart. This was just as well, for plenty of irritants remained. On 27 July Tritton wired Stern in London that the drawings supplied to him by Crompton and one of Fosters’ own men, Mr Rigby, were mere sketches and that until proper ones arrived work was at a standstill. Stern was at his best prodding laggards and the detailed drawings soon arrived. On 9 August he attended a meeting chaired by Dr Addison of the Munitions Invention Committee on the subject of money for landships. It was agreed that £80,000 should be made available, out of which some £10,000 had been spent. It was the matter of money that had finally finished Colonel Crompton. The estimate for his Rolls-engined landship had come from the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Company and it amounted to £68,676. Such amounts were far beyond thinking about.

Wilson and Tritton and Fosters’ workmen produced without too much difficulty a large metal box driven by the Daimler engine and mounted on Bullock tracks. These last caused all the trouble, for the ones sent by the American factory were badly made and of inferior metal. As soon as the machine moved around the factory floor they either snapped or fell off. The Giant machines were still under test at Burton under the care of Hetherington and Squadron 20. Reports came to Fosters’ works that the machine was proving a good wire-crusher but when it came to crossing trenches something in the way of a differential lock was needed. One track on land and the other hanging over a drop made the whole machine useless. Wilson left Tritton working on tracks at Lincoln and hurried north. Already the two men had come to the conclusion that the armoured box would not do and were moving towards something better. The nature of this was not committed to paper but by late August d’Eyncourt was writing to Stern that he should go at once to Lincoln and hurry Tritton along with whatever he was doing. In fact both Tritton and Wilson were working at speed almost beyond belief. Wilson was constantly travelling between Lincoln, Burton and Coventry in intervals between working at drawing board and on factory floor. There was plenty to occupy him. Designs for a transmission system for the second machine took much time; work on more serviceable tracks took even more. D’Eyncourt, in desperation, suggested that they try Balata belting. Little Willie, as the armoured box came to be called, waddled round the factory on 6 September under his own power.

The Killen-Strait tractor faces barbed wire.

On 22 September Stern received the famous telegram, handed in at Lincoln: ‘Balata died on test bench yesterday morning. New arrival by Tritton out of Pressed Plate. Light in weight but very strong. All doing well thank you. PROUD PARENTS’. In a letter written after the war Wilson complained that Stern gave undue prominence to this cable. By that time, however, they had fallen out and he goes on to grumble about ‘the absurd scramble for credit that developed later’. For the moment everybody was happy in the White Hart.

On 19 September Tritton and Wilson decided to leave Little Willie to be completed by Fosters’ people and to concentrate on his successor. This was a far longer business than the building of the first machine. Sketch followed sketch, two like-minded men beavering away with nothing to guide them in the direction of a machine that would change the face of war and the composition of armies. It was Wilson who first drew out the shape of a slightly deformed rhomboid but both men spotted at once the possibility that they had found what they were seeking. The track would run on rollers round the entire circumference; this would prevent top-heaviness. The nose would be cocked-up and would thus get some sort of grip upon the face of any bank it might have to climb. The engine would go amidships, driving toothed wheels called sprockets at the rear and the sprockets would push the track over the rollers and an idler wheel in the bows, laying it down as if it were a carpet.

It is commonly said, even by Stern, that the underside was deliberately made as the arc of a 16 foot wheel. Wilson says flatly that this is nonsense. First mention of it comes in Williams-Ellis’ The Tank Corps published in 1919. Wilson was very cross, for professional engineers would see the absurdity of the proposition and would blame him. As the book was quasi-official, he wrote a protest ‘but without result’. Wilson’s contribution was the transmission system, of which more later. Even working at their pace it took the two men from August, 1915, until January, 1916, to produce the first sample of their work.

Little Willie – presumably named for the Crown Prince – was given his road trials on 15 September. Tritton and Wilson now found him rather a bore but they had to be there. Swinton (then Secretary of the CID) told the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors after the war how it had all gone. ‘I was asked my opinion and I said that Willie would not do. He did not comply with the specification sent from France and could not climb a 5 foot vertical height. Little Willie was a steel box.’ Swinton was quite right and nobody disputed it. Little Willie was what the cavalry calls ‘cast’. He spent the next few years ingloriously lying around and after the war was shifted to the Tank Museum at Bovington. There you may see him, as good as new.

In 1919 Stern’s book Tanks: The Log Book of A Pioneer was published. In the following year Wilson presented a copy to his friend and colleague Major Buddicum of the Tank Corps who had been a member of the design team during the early days. Attached to it were a number of notes from which the sequence of events during the late summer and autumn of 1915 can be extracted. It was during August that Wilson suggested to Tritton ‘a quasi-rhomboidal shape with tracks running outside’. On 24 August Tritton submitted a sketch to d’Eyncourt who approved and told him to get on with it. Two days later, at Tritton’s request. Stern came to Lincoln with a specification drawn up by Swinton. Immediately after this visit work began on the machine that was to become known as ‘Mother’. At the end of September a ‘mock-up’ had been completed and this was taken by lorry to Wembley for Stern to show to a party of senior officers. All save General von Donop approved of what they saw; the MGO’s objection was to the wooden gun which had been put in without his consent.

A Mark I Tank with original tail attachment.

On 30 September Stern, with authority from the Landship Committee, instructed Tritton to go ahead and make the machine whose model had been shown. One difficulty remained. Nobody knew where to mount the gun. If in front it would dig into the ground whenever the nose went down. The roof was plainly out of the question. D’Eyncourt came up with the answer. The Navy constantly had to mount guns along the sides of ships capable of being swivelled about over many degrees. It was done by ‘sponsons’, steel boxes protruding from the side and bolted on to it. Stern made a sketch and sent it to Tritton who developed an exact drawing of what was needed. Admiral Singer agreed to let the Committee have some surplus 6-pdrs which ought to fit nicely into it. The guns were 8 feet long and 6 feet from the centre. Two sponsons plus two guns added three tons to the weight of the Wilson. The Daimler engine, designed only for a big tractor, had another burden added; but sponsons were clearly the answer and sponsons were made.

There were only enough track plates to make up one side of the new machine by the end of November but more were being fabricated. The hull was ready on the 23rd, the engine and gear-box a day or two later. Stern was, metaphorically, hopping from one foot to the other in his anxiety to have something substantial to show off. No doubt his pestering was a nuisance and quite needless. The job would be done when the men were finished and not before. On 3 December, 1915, they announced themselves ready for the first trial.