LET us LEAVE THE LANDSHIPS for a moment and return to Baker-Carr in France. For a long time he had been trying to force a great truth into unreceptive minds. The Vickers gun, a better and lighter Maxim, was not the same thing as a Lewis gun. The Vickers, weighing just under half a hundredweight and mounted upon a tripod of about the same, was a true machine-gun. It could, and should, be used to fire by means of instruments from a position where it could neither see nor be seen by its target. The long beaten zone – at a range of 1,000 yards it swept an ellipse 150 yards long by 15 across at its widest point – could interlock with the beaten zones of many other guns and smother large areas with bullets by day or night. The Lewis, though an excellent weapon, was a mere automatic rifle. Vickers guns should be grouped together and worked by specialists, leaving the Lewis as a bonus for infantry. In October, 1915, Baker-Carr got his way. The Machine Gun Corps came into being, as distinct from other Corps as were Gunners or Sappers. One hears and reads much of the excellent German machine-gunners. Few people now remember that the Machine Gun Corps had them beaten all ends up. By the end of the war 170,000 men had passed through its ranks and its dead numbered more than 13,000. The Tank Corps, at the peak of its strength, never reached 20,000 all ranks.

It had taken the personal order of Lord Kitchener to get for Baker-Carr the first 40,000 men he needed for the new arm of the service. The Adjutant-General, Sir Henry Sclater, had refused point-blank, with the words ‘Can’t be done’. Nor was this mere stubbornness. A secret paper for the Cabinet printed in October over the initial K began with the words ‘The voluntary system, as at present administered, fails to produce the numbers of recruits required to maintain the Armies in the field. The returns show that the total yield is much less than the 35,000 a week required.’ Two days previously, on 6 October, Lord Kitchener had had to turn down a proposal from Mr Lloyd George at the Ministry of Munitions for the supply of a thousand heavy guns over and above those already ordered by the War Office. The Army simply could not find the men. Already it had to scrape up from somewhere nearly 2,000 officers and 43,000 other ranks to man the guns already ordered but not delivered. It was no time to demand men for a new and possibly futile venture. Lord Kitchener had suggested sending to Russia guns that the Army would one day need. If he was to be induced to invest in armoured vehicles he would need a lot of persuasion, quite apart from the factor of which Baker-Carr spoke. ‘The average Englishman’s deep-rooted dislike and mistrust of machinery in general’.

Some Englishmen, professional and enthusiastic amateur alike, were trying to overcome it. Syme had produced armour plate, with the help of the Beardmore company, that would more often than not keep out the ordinary German ‘S’ bullet. On 24 June, six days before the Wormwood Scrubbs demonstration, General Scott-Moncrieff (now Chairman of the Landship Committee) had come up with ideas for arming the vehicles with a two-pounder pom-pom either side of the bows, two machine-guns further back and loopholes wherever possible for musketry. The pom-pom, though made by Vickers, was not a British service weapon. A number of them had been captured during the Boer War and were used, whenever spare parts could be found, as anti-aircraft guns. A few had gone to France during the early days of desperate expedients and had been found useful for clearing villages. All the same, these were weapons off the scrap-heap, for the Army had nothing better to offer. A 2.95 mountain gun – Kipling’s screw-gun – was lent to Stern but it was obviously unusable. An experimental mortar, firing a 501b bomb, was tried out at the Clement-Talbot works in Barlby Road, Kensington, where the armoured cars still had their HQ. Again it was plainly not what was wanted.

Syme was deputed to try his luck with the Navy which had a number of small guns dating from the ’80s and were designed as secondary armament for shooting at torpedo boats. Here he had better fortune. The 2 and 3 pounders were, for various reasons, unsuitable but the 6-pdr seemed to be just what was wanted. The Navy agreed to provide as many as it could. This gun, with its barrel shortened, became the standard tank weapon throughout the war.

The exhibition at Wormwood Scrubbs on 30 June had been no more than an expedient to keep up interest in mechanized warfare, the only real turn being the demonstration of wire-cutting by the Killen-Strait tractor but Mr Lloyd George (now Minister of Munitions), Mr Churchill and the entire Committee came to watch it. For Stern it was an opportunity, probably of his own creation, to keep in personal touch with Lloyd George whom he had, of course, known passably well in financial circles. The future of Mr Churchill seemed doubtful but LG had to be kept well disposed. Stern, as later correspondence shows, was also at pains to cultivate the great man’s secretary-cum-mistress, Frances Stevenson, who was at this time worrying both the Minister and herself with an unfounded belief that she was pregnant. Such an ally was not to be despised.

On 29 September, 1915, Squadron 20 brought a full-sized model of Little Willie’s successor to Wembley for examination by invited officers from the War Office and GHQ. Sir John French sent his aide Major Guest, a stockbroker by trade and Sir John’s main link with the outside world. Guest’s report cannot have been enthusiastic; when Sir Douglas Haig took over three months later there was nobody at GHQ who could tell him anything about what was happening over the development of a fighting vehicle.

For Tritton the show was a triumph, and a deserved one. As recently as 27 July he had had to send an agitated telegram to Stern saying that the drawings given him were mere sketches and until proper ones were in his hands no work could even be started. Within a couple of months Fosters had turned out the model of a recognizable tank. Nearly all the spectators, of whom only Mr Moir of the Inventions Board was a civilian, were suitably impressed. Only General von Donop thought little of it. He complained that the whole business was highly irregular and, worse, that artillery pieces were being used without his approval.

This was the kind of thing Stern had come to expect and he took no notice. On the following day he gave Tritton instructions to build ‘Mother’ in accordance with the Committee’s plans. As might have been expected another complication immediately arose.

Men engaged in munitions production had been issued with badges, the possession of which demonstrated that they were not hanging back. The work at Fosters, being of a highly secret nature, was not reckoned by the War Badge Department to qualify. Many of Fosters’ best men, sick of being accused of ‘dodging the column’, began to leave. Correspondence achieved nothing. Stern marched down to the office in Abingdon Street, threatened to bring Squadron 20 to take the place by force, and marched out with a sackful of badges. A couple of years later Albert Thomas, the French Minister of Munitions, complained officially of Stern’s ‘bullying methods’ and he may have had a point. Bullying is sometimes necessary with Government departments. On this occasion Tritton wrote that he ‘was very grateful to you for the trouble you have taken in the matter and I feel I must congratulate you on the promptness with which you have overcome the entanglement of red tape’. Work on ‘Mother’ was resumed. On 3 December her trials took place at Lincoln and ‘were very successful indeed’. D’Eyncourt, wishing to find out what happened when a 6-pdr was fired from a sponson, arranged to have the machine taken to a lonely field outside Lincoln, within a mile of the Cathedral, for practical tests. Hetherington and Stern motored up with some rounds of solid armour-piercing shot. Early in the morning ‘Mother’ was driven into position, Hetherington took his place at the gun and pressed the trigger. Nothing happened. While he and Stern were examining the breech the gun suddenly went off of its own accord and the shot headed towards the Cathedral. Two hours of consternation and digging followed until it was found buried in the earth.

Then came trials of the lighter weapons. Enfield Lock produced specimens of Vickers, Lewis, Hotchkiss and Madsen guns. Where this last came from is a mystery; it would have been the ideal weapon. There seems no obvious reason why the existing gun should not have been copied but people were punctilious about patent rights in 1915. The Hotchkiss was chosen as second best. The bulky cylinder surrounding the cooling flanges of the Lewis made this excellent weapon hardly practicable for use in a sponson’s loop-hole. Nor was its drum of cartridges as handy as the clip employed by the Hotchkiss.

By Christmas ‘Mother’ was in all respects ready for service. A full meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence was held on Christmas Eve with Scott-Moncrieff in the chair; Swinton was present in his new capacity of Assistant Secretary with Stern and d’Eyncourt representing the Admiralty. The first item on the agenda was a paper prepared by Swinton entitled ‘The Present And Future Situation Regarding The Provision Of Caterpillar Machine-Gun Destroyers Or “Land Cruisers”’. There was no longer any mention of mere armoured personnel carriers; these machines were to seek out and destroy in regular naval tradition. Much of the paper dealt with matters of only transient interest, such as manning the RNAS Squadrons, the only Service personnel so far engaged, the organization of Committees and the important question of who should pay for what. So far every penny had come out of the Navy Vote and the Navy did not much care for it. On one point Swinton made a firm recommendation. ‘To whatever Department the production of the Caterpillars is finally allotted, it is suggested that it be entrusted to one business man of proved capacity, preferably one who has been connected with the experimental construction up to date.’ It is not hard to guess the name he had in mind. Stern notoriously hated all Committees.

This was a little too much for the War Office to swallow. Sir Charles Callwell, brought from retirement to be Director of Military Operations at the War Office, has left on record that body’s distrust, based on experience, of The Man of Business and The British Working Man. To appoint a Tank Supply Dictator would be going too far, but a fair compromise was reached on 12 February, 1916. There would be a Tank Supply Committee, as an off-shoot of the Ministry of Munitions with Stern as President and Wilson, Swinton, Syme and Mr Bussell of the Admiralty Contracts Branch as Members, along with two soldiers from branches of the War Office. D’Eyncourt, not being able to give anything like all his time to Landships, was appointed a Consultant. The Committee was empowered to place orders on its own authority and would be given a Bank Account starting with ‘the estimated cost of fifty machines’. When they were made they would be handed over to the War Office whose business it would be to find and train crews. The officers of the RNAS engaged in tank affairs would ‘cease to belong to that Service’ and arrangements would be made ‘for their appointment as military officers with rank suitable to the importance of their duties’. The War Office reckoned that the equivalent of an infantry company commander was quite high enough. Stern and Wilson became Majors; though Stern did achieve one step to Lieut-Colonel, Wilson was never promoted above his new rank. Holden, even when he became British Representative in America, remained no more than a Captain. Admiral Singer undertook to supply a hundred 6-pdr guns by June, 1916, but ‘it was not possible at the moment to say how many of them would have non-recoil mountings’.

The word ‘Tank’, coined by Swinton, seems to have crept into the records of the Committee almost by accident. Clearly some jargon word was needed and, though no mention is in the record, everybody agrees that it was debated. ‘Water Carrier’ was suggested but turned down; the initials by which it would certainly be called were misleading beyond necessity. The first machine was called by various names at the beginning. In letters it can be found as ‘Big Willie’, ‘Wilson’, ‘Centipede’ and ‘HMS Caterpillar’, before there was general agreement on ‘Mother’. Even this was confusing, for it had already been adopted by Gunners for the first 9.2 howitzer. ‘Mother’, however, stuck; ‘Willie’ was not lost, for in everyday speech tank men usually referred to their ships as either ‘Willies’ or ‘buses’. And, as everybody knows, ‘My Boy Willie’ is still the quickstep of the Royal Tank Regiment.

Everything now turned on the success or otherwise of the demonstrations. Wembley, being too open to the public, would not do. Stern and d’Eyncourt sought out Mr McCowan, Lord Salisbury’s agent, and obtained from him the use of a part of Hatfield Park. A company of Hertfordshire Volunteers, under RE supervision, dug trenches and put up wire. Squadron 20 oiled, greased, polished and painted ‘Mother’ in proper Bristol-fashion. Her first performance in front of an audience bound to be highly critical was fixed for 29 January, 1916.

The audience was almost entirely a Service one, the only exceptions being people immediately concerned with Landships. One officer who might have wished to be there was not. Lieut-Col W. S. Churchill, OC 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers, was with his battalion at Plug Street. The 9th Division, of which his unit formed a part, had had a very rough passage at Loos. The Divisional General, Thesiger, had been killed and his place had been taken by W. T. Furse who was to succeed von Donop as MGO at the end of the year. Colonel Churchill was at that moment a worried officer. On 3 December, 1915, before taking command, he had written his famous paper ‘Variants of the Offensive’. A copy had gone to the Committee of Imperial Defence and a proof had been returned to him. While the Colonel was addressing himself to revising the paper his HQ came under heavy shell fire and he ‘did not suggest that my departure was hurried, but neither was it unduly delayed.’ When he returned to his room an hour and a half later the paper was gone. Terrible thoughts of spies, about whom there had been many warnings, sprang to the mind. Even then this frightfully important paper might be in an aeroplane bound for the Fatherland. Colonel Churchill had a very bad time until three days later he found the missing sheets in an inside pocket of a jacket that he hardly ever used.

A copy of the paper had gone to GHQ, BEF. On 25 December Sir Douglas Haig had written in the margin ‘Is anything known about these caterpillars referred to in para. 4, p. 3?’. The answer being negative a 35-year-old Lieut-Colonel of Sappers named Hugh Elles was sent home to find out. Elles must have gone quietly about his business for his name does not figure in the lists of those present at the two Hatfield tests.

The conditions in which ‘Mother’ was to operate were based on those of the battle of Loos, which was a pity. During the days of preparation for ‘Mother’s’ debut great numbers of German guns of immense power were being turned upon the brave defenders of Verdun. Loos was already ancient history and new dimensions of warfare were being introduced. In France, Sir Douglas Haig needed no telling that before long it would be the imperative duty of the British Army to find some way of taking pressure off the French before they collapsed.

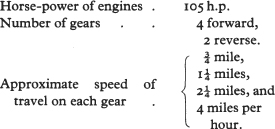

There was in ‘Mother’ about every fault that a tank could have. The 90 plates on each track were fabricated from brittle steel: the 105 hp Daimler engine was not powerful enough: the exhaust lacked a silencer, trailed over the top, belched out smoke and became red hot: lubrication was simply by means of oil swilling around in a trough: the petrol tanks were inside, up in the bows and fed the carburettor by gravity, with the result that when nose-down supply was cut off: the machine was steered as an oarsman steers a skiff, pulling on one side but not the other, with the assistance of a pair of large iron wheels trailing behind and worked hydraulically. All that said, she was a genuine armoured fighting vehicle and the only one in the world. Immense credit is due to Fosters. The whole business had had to be carried out in the utmost secrecy and here again Fosters had shown good East Anglian sense. When asked what they wanted in the way of guards and such Tritton had replied that the only way of drawing attention to the strange activities of harmless agricultural instrument makers would be to surround the place with sentries. Work had simply gone on as usual.

It took eight men to drive and fight the Mk 1 Tank. This rather large number was due to the transmission system. Up in front was the driver, sitting alongside the subaltern in command. He had two levers, one for each track, and a clutch connected to a two-speed gear box; the drive then continued through a differential which was fitted with a secondary two-speed gear-box on the outer end of each shaft. These were the care of two gearsmen who worked them with hand-levers. It then continued by chains to the driving sprockets – the toothed wheels at the stern which engaged with the underside of the track and drove it forward – the front wheel being a mere idler. Only about five feet of track was in contact with the ground, with the result that the tank always had a slight rocking motion. As the point of balance was in the middle an experienced driver could see-saw the machine over the edge of a jump and lower it fairly gently over steep drops. If the gravity feed failed it was necessary to pour petrol into the carburettor out of a can; not a pleasant exercise against a hot exhaust inside a fume-filled metal box. The gunners and their mates knelt inside the sponsons, adding cordite fumes to the stench of petrol and contributing substantially to the already hellish din of the engine. To swing the machine it was necessary to lock the differential and signal to one gearsman by hand to put his side into neutral. The officer then applied the brake on the same side and the tank turned pretty well on its axis.

None of this, apart from the smoke, could be understood by observers. The Programme for the first test was printed and this is how it read.

‘TANK’ TRIAL

DESCRIPTION OF ‘TANK’

THIS machine has been designed, under the direction of Mr E.H.T. d’Eyncourt, by Mr W. A. Tritton (of Messrs. Foster, of Lincoln) and Lieutenant W. G. Wilson, R.N.A.S., and has been constructed by Messrs. Foster, of Lincoln. The conditions laid down as to the obstacle to be surmounted were that the machine should be able to climb a parapet 4 feet 6 inches high and cross a gap 5 feet wide.

| Over-all Dimensions | ||

| Feet | Inches | |

| Length . . . . | 31 | 3 |

| Width with sponsons . | 18 | 8 |

| „ without sponsons | 8 | 3 |

| Height . . . . | 8 | 0 |

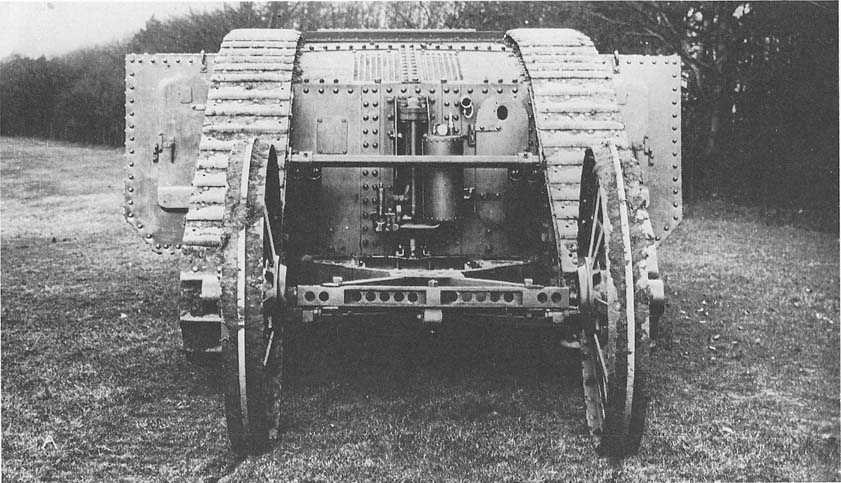

‘Mother’s’ rear view.

Protection

The conning tower is protected generally by 10 millim. thickness of nickel-steel plate, with 12 millim. thickness in front of the drivers. The sides and back ends have 8 millim. thickness of nickel-steel plate. The top is covered by 6 millim. thickness of high tensile steel, and the belly is covered with the same.

| Weight | ||

| Tons | Cwt | |

| Hull . . . . | 21 | 0 |

| Sponsons and guns . . | 3 | 10 |

Ammunition, 300 rounds for guns and 20,000 rounds for rifles1 . . |

2 | 0 |

| Crew (8 men) . . . | 0 | 10 |

| Tail (for balance) . . | 1 | 8 |

| ___________ | ||

Total weight with armament, crew, petrol, and ammunition. . . |

28 | 8 |

1 Removable for transport purposes.

Armament

Two 6-pr. guns, and

Three automatic rifles (1 Hotchkiss and 2 Madsen).

Rate of Fire

6-pr.: 15–20 rounds per minute.

Madsen gun: 300 rounds per minute.

Hotchkiss gun: 250 rounds per minute.

NOTES AS TO STEEL PLATE OBTAINED FROM EXPERIMENTS MADE

Nickel-Steel Plate

12 millim. thickness is proof against a concentrated fire of reversed Mauser Bullets at 10 yards range, normal impact.

10 millim. thickness is proof against single shots of reversed Mauser bullets at 10 yards range, normal impact.

8 millim. thickness is proof against Mauser bullets at 10 yards range, normal impact.

High Tensile Steel Plate

6 millim. thickness will give protection against bombs up to 1 lb. weight detonated not closer than 6 inches from the plate.

(N.B.—It is proposed to cause the detonation of bombs away from the top of the tank by an outer skin of expanded metal, which is not on the sample machine shown.)

PROGRAMME OF TRIALS

Reference to Sketch, Plan, and Sections

The trial will be divided into three parts, I, II, and III

―――――

Part I.—Official Test

1. The machine will start and cross (a) the obstacle specified, i.e. a parapet 4 feet 6 inches high and a gap 5 feet wide. This forms the test laid down.

Part II.— Test approximating to Active Service

2. It will then proceed over the level at full speed for about 100 yards, and take its place in a prepared dug-out shelter (b), from which it will traverse a course of obstacles approximating to those likely to be met with on service.

3. Climbing over the British defences (c) (reduced for its passage), it will—

4. Pass through the wire entanglements in front;

5. Cross two small shell craters, each 12 feet in diameter and 6 feet deep;

6. Traverse the soft, water-logged ground round the stream (d), climb the slope from the stream, pass through the German entanglement;

7. Climb the German defences (e);

8. Turn round on the flat and pass down the marshy bed of the stream via (d), and climb the double breastwork at (f).

Part III.—Extra Test if required

9. The ‘tank’ will then, if desired, cross the larger trench (h), and proceed for half a mile across the park to a piece of rotten ground seamed with old trenches, going down a steep incline on the way.

January 27th, 1916.

The trial course, though it did not bear close resemblance to any 1916 battlefield, was an honest effort to show what a tank could do. One thing was missing. Cold January weather does not provide mud. Nobody could have been expected to appreciate that the bigger guns now coming into use on both sides could do things other than kill men and smash their works. They had an unprecedented ability to turn great tracts of good agricultural land into bottomless lakes of brown porridge.

This, however, was for the future. ‘Mother’ having behaved very well on 29 January, d’Eyncourt wrote next day a personal letter to the man who, above all others, could decide her fate. His message to Lord Kitchener was unequivocal in its terms. ‘The machine has had a satisfactory preliminary trial at Hatfield and proved its capacity, and I trust your Lordship may be able to come there and see a further trial on Wednesday afternoon next, February 2nd, when you will have an opportunity of judging its qualities yourself.’

Kitchener, though still the nation’s most revered soldier, had never suffered from Baker-Carr’s Military Mind. He accepted with alacrity; so did Mr Balfour, Mr Lloyd George, General Robertson and a long list of grandees both naval and military of whom Maurice Hankey was one. The earlier demonstration had been important but this one was crucial. Tritton, Wilson, d’Eyncourt, Swinton and Stern would have been more than human had they not endured much trepidation.

In spite of all the prospects of a successful performance d’Eyncourt cannot have been a happy man. On the same day, 29 January, 1916, the first of his great steam-driven fleet submarines, K 13, had sunk on her trials with the loss of 31 good men.

The petrol was turned on, four men swung the huge starting handle and the Daimler engine burst into life. Dense clouds of smoke belched from the exhaust but the machine, bearing the name HMLS Centipede, trundled round the course. Mr Lloyd George was captivated; ‘I can recall the feeling of delighted amazement with which I saw for the first time the ungainly monster plough through thick entanglements, wallow through deep mud and heave its huge bulk over parapets and across trenches,’ he wrote nearly twenty years later. ‘At last, I thought, we have the answer to the German machine-guns and wire. Mr Balfour’s delight was as great as my own and it was only with difficulty that some of us persuaded him to disembark from HM Landship whilst she crossed the last test, a trench several feet wide.’ AJB, having extruded his lanky frame through the little door below one of the sponsons was heard to remark plaintively that there must be some more artistic way of leaving a tank. There was none. To enter, it was necessary to stoop under the sponson, insert the head and trunk and finally pull up the feet; to leave one lowered the feet until they touched ground and then folded the body downwards until the head was clear. On Lord Salisbury’s golf course it cost a number of bruises; in action, with the machine on fire, it took great good fortune to emerge at all. The last resort was a small manhole in the roof, provided with holes for revolver fire at intruders; it would have admitted only a very undersized man in great desperation. Once the engine had warmed up the inside temperature commonly touched 125°.

It was satisfactory to have made allies of the Minister of Munitions and the First Lord of the Admiralty, but one man remained with power of life or death in his hands.

It is odd how much nonsense has been written about Lord Kitchener’s attitude to the first tank, and this would have pleased him. His whole military life had been spent among people of devious minds and his own had been shaped in the Near East. He trusted none of his Cabinet colleagues any more than he had once trusted the Mudir of Dongola and with good reason. ‘Leaky’ was the adjective he applied to them more than once. When, during his Egyptian days, he had been faced with any dogmatic statement about anything the natural consequence would have been for him to ask himself not ‘Is that true?’ but ‘Why did he say that?’ So he managed his own affairs. Lord Kitchener ostentatiously left the demonstration before it was over, announcing that the tank would soon be knocked out by artillery and that the war would not be won by such things. Even Sir Basil Liddell Hart, in his obituary of Swinton in the Dictionary of National Biography, says simply that ‘Kitchener dubbed it a pretty mechanical toy “which would be quickly knocked out by the enemy’s artillery”’ and leaves it at that. No doubt Lord K did say something of the kind. The deception plan plainly worked well. It deceived most historians.

Of all people, it was Mr Lloyd George who brought the truth to light. In his War Memoirs, written during the years 1933 and 1934, he tells of the demonstration and of Kitchener’s departure. Then, to his eternal credit, he quotes from ‘a letter I have quite recently received from General Sir Robert Whigham, who in 1916 was a Member of the Army Council and accompanied Lord Kitchener to the Hatfield trial.’ He writes: ‘Lord Kitchener was so much impressed that he remarked to Sir William Robertson that it was far too valuable a weapon for so much publicity. He then left the trial ground before the trials were concluded, with the deliberate intention of creating the impression that he did not think there was to be anything gained from them. Sir William Robertson followed him straight away, taking me with him, to my great disappointment as I was just going to have a ride in the tank! During the drive back to London, Sir William explained to me the reason of Lord Kitchener’s and his own early departure, and impressed on me the necessity of maintaining absolute secrecy about the tank, explaining that Lord Kitchener was rather disturbed at so many people being present at the trials as he feared they would get talked about and the Germans would get to hear of them. It is a matter of history that after these trials fifty tanks were ordered and that Lord Kitchener went to his death before they were ready for the field. I do know, however, that he had great expectations of them, for he used to send for me pretty frequently while he was S of S and I was DCIGS, and he referred to them more than once in the course of conversation. His one fear was that the Germans would get to hear of them before they were ready.’

His good deed for the day done, Mr Lloyd George returned to form. ‘If this is the correct interpretation of Lord Kitchener’s view, I can only express regret that he did not see fit to inform me of it at the time, in view of the fact that I was responsible as Minister of Munitions for the manufacture of these weapons.’ Lord Kitchener, one may suspect, ranked Mr Lloyd George somewhere below the Mudir of Dongola as a trustworthy confidant.

Stern says that before Robertson left the ground he told him that ‘orders should be immediately given for the construction of these machines’, though he makes no mention of numbers. General Butler, Haig’s Deputy CGS, asked how soon he could have some and what alterations could be made. Stern, regardless of the gulf between General officers and Lieutenants RNVR, told him flatly that if GHQ wanted any in 1916 no alterations could be made, except to the loop-holes in the armour.

D’Eyncourt sent an ebullient letter to his former First Sea Lord, still commanding his battalion of Jocks at Plug Street and, between duties, sketching his HQ at Lawrence Farm. ‘Dear Colonel Churchill, It is with great pleasure that I am now able to report to you the success of the first landship (Tanks we call them). The War Office have ordered one hundred to the pattern which underwent most successful trials recently … The official tests of trenches, etc., were nothing to it, and finally we showed them how it would cross a 9 feet gap after climbing a 4 feet 6 inches high perpendicular parapet. Wire entanglements it goes through like a rhinoceros through a field of corn. It can be conveyed by rail (the sponsons and guns take off, making it lighter) and be ready for action very quickly. The King came and saw it and was greatly struck by its performance, as was everybody else. It is capable of great development, but to get a sufficient number in time I strongly urged ordering immediately a good many to the pattern which we know all about. As you are aware it has taken much time and trouble to get the thing perfect and a practical machine simple to make; we tried various types and did much experimental work. I am sorry it has taken so long but pioneer work always takes time, and no avoidable delay has taken place though I begged them to order ten for training purposes two months ago. After losing the great advantage of your influence I had some difficulty in steering the scheme past the rocks of opposition and the more insidious shoals of apathy which are frequented by red herrings, which cross the main line of progress at frequent intervals. The great thing now is to keep the whole matter secret and produce the machines all together as a complete surprise. I have already put the manufacture in hand, under the aegis of the Minister of Munitions, who is very keen; the Admiralty is also allowing me to continue to carry on with the same Committee, but Stern is now Chairman. I enclose photo. In appearance it looks rather like a great antediluvian monster, especially when it comes out of boggy ground, which it traverses easily. The wheels behind form a rudder and also ease the shock over banks etc. but are not absolutely necessary, as it can steer and turn in its own length with the independent tracks.’ D’Eyncourt ended with his ‘congratulations on your original project’ and good wishes.

Admiral Singer, Director of Naval Operations, was sufficiently taken by the demonstration to propose a machine three times the length and with ‘3 feet protection over fore part’. Though this may have been premature, the Army Council on 10 February sent to Their Lordships formal congratulations to everybody concerned, including the much-humbugged Squadron 20. ‘The thanks of the War Office are thoroughly well deserved,’ replied Mr Balfour.

From being a friendless and despised orphan of doubtful legitimacy the Tank had, at a bound, become the friend of man. It would have to do remarkably well to live up to what everybody now expected. Contracts went out to the Metropolitan Carriage Wagon and Finance Co, Armstrong Whitworth, to Kitson Clarke of Leeds, Marshalls of Gainsborough and the North British Locomotive Company of Glasgow. The engineers, once it had been explained to them, undertook to build Tanks with every possible speed. Hankey, not a convert but an original believer, wrote to Swinton on 7 February, ‘I shall get as many Tanks as they will let me have. Hundreds, I agree, are necessary.’ His diary entry for the day of the Trial did not carry modesty to excess: ‘A great triumph for Swinton and me as we have had to climb a mountain of apathy and passive resistance to reach this stage.’ It is possible that D’Eyncourt, Stern, Tritton, Wilson and even Colonel Crompton might have taken another view.

The specifications, it will be remembered, spoke of Madsen guns. These excellent weapons, in appearance much like the Bren, would have been by far the most suitable. They formed part of the agenda for a CID meeting on 21 June. Hankey explained that 900 had been ordered from Copenhagen and half the price of £230,000 had been paid. There was, however, a difficulty. The Roumanians, lured at last into the Allied camp, wanted them too, and were proposing to order a further 1500. Mr Lloyd George told the meeting that the Danes would not part with them except to neutrals. If the Roumanians took them they would have to go through Russia, ‘and the Russians would probably taken them en route’. The Prime Minister observed that ‘the Roumanians could be told that they could have them if they would arrange for getting them. He thought it doubtful that they would ever arrive in Roumania but we should be making a show of virtue.’ Nobody mentioned that the War Office, in a letter dated 5 February, three days after the trials, had told the Committee that ‘they do not require any Madsen guns for equipment’. This is hard to explain away. The guns, badly needed, were bought and half paid for. Even though the United States was in its semi-permanent condition of a Presidential election it ought to have been possible to find a well-disposed neutral to make the necessary arrangements. Instead of that, merely to ‘make a show of virtue’, this invaluable weapon was thrown away. What happened to them is unclear. There are many photographs of German cavalry equipped with the Madsen; certainly, by one means or another, that is where they ended up.

After guns came men. In France there were fifty-two regiments of cavalry, eleven of them Indian, with an average strength of 600 each. Timid suggestions were made to Sir Douglas Haig that some economies might be made in this department. His answer was uncompromising. ‘I am very strongly of opinion that no reduction should be made in the Cavalry and it is essential, looking to the future, that the Cavalry should be thoroughly trained, as Cavalry, throughout the ensuing winter.’ Before that letter was written the Battle of the Somme had been fought.