FINDING MEN FOR THE ARMY is the business of the Adjutant-General’s Department, and Sir Henry Sclater did not welcome the additional demand. During 1915 he had had to produce men for a variety of new units, from Mobile Bath Sections and Blanket Delousing Companies to the Machine Gun Corps and the Welsh Guards. Swinton was the obvious person to take on the day-to-day running of the Tank people and, in order to tidy up loose ends, he was appointed to command a body to be known as the Heavy Section (sometimes Heavy Branch) of the six-month-old Machine Gun Corps. It was tactfully – reasonably tactfully – made clear to him that at his time of life he could not expect to lead it into battle, but he must first of all assemble it and then give it whatever training might occur to him as appropriate.

There was an existing body of men that could serve as a nucleus. Early in the war there had come into being a unit called the Motor Machine Gun Corps. It had been modish among young men with cars or motor-cycles of their own, or at any rate with experience of other peoples’ cars or motor-cycles, and it had acquired recruits who would not have been over-enthusiastic about joining the older established regiments. In particular it had attracted into its ranks quite a number of what were then called Colonials, some from Colonies whose allegiance had been renounced quite a long time ago. There was Captain Kermit Roosevelt, son of ex-President Theodore, and several Canadians who claimed to come from Provinces with names like New York and Texas. They were a very welcome accretion of strength, especially at a time when recruiting had so fallen off that conscription was coming in. In addition to them there were men of vaguely seafaring antecedents, lately of Squadron 20 RNAS. The Squadron, when threatened with collective transfer to the Army, had declined to oblige, but a good many men who had seen the beginnings of the Tank were determined to share its fortunes. Stern and Wilson, as already mentioned, were transferred in the same way, each with the rank of Major, MGC. Hetherington, already an Army officer in spite of his rank of Flight Commander RNAS, was similarly promoted. None of them, of course, was expected to become a Regimental officer. Stern, after a skirmish between the War Office and the Ministry of Munitions, each of which claimed to own him, was seconded to the Ministry as Chairman of the Tank Supply Committee, with Wilson and Syme both members. Sueter did not remain for long but returned to his first love, the flying service.

As had always happened, and as would happen again a generation later, a call was made for volunteers to serve in something new and exotic. The word was passed round, rather as it had been at the time of the South Sea Bubble, for ‘a Company for carrying on an undertaking of Great Advantage but no one to know what it is’. All that was known was that the volunteers sought should have some mechanical or engineering experience and there was talk of an experimental armoured car unit. It sounded rather attractive, certainly a lot more attractive than infantry life, and men of the right calibre came in. The mystery deepened for two of them. A temporary camp, to which they were bidden to report themselves, had been set up at Bisley. On arrival they were told that the Motor Machine Gun Corps had left two days earlier for Siberia. It was nothing to do with Locker Lampson’s squadron; Siberia was the code-name of a new camp a few miles away. Russia had been pressed into service as part of the deception plan, the men making the tanks being told that they were water-carriers for the Czar and words in Cyrillic script adorned their sides. Whoever thought the idea up did not know his East Anglians. They have never been that easily fooled; but they kept their thoughts to themselves in the East Anglian way and asked no questions.

The first specialist instruction given was in the Vickers and Hotchkiss machine-guns. When a reasonable competence in these had been attained the plot was thickened by sending everybody to Whale Island where Naval Petty Officers taught them the mysteries of the six-pounder gun. That done, and filled with rumours about the strange machines to whose service they were assigned, they were encadred into a battalion and sent by train to Elveden, near Thetford in Norfolk. Once there the new tank men found themselves wrapped in a security not seen again until the eve of ‘D’ Day. Five square miles of Norfolk had been cut off from the world. Every farm and cottage had been evacuated, the road running through it closed and nobody was allowed in without a pass. Sentries were posted everywhere, reinforced by patrols of cavalry, and aircraft were forbidden to fly over the area on pain of being shot down. Once in, it was only possible to leave upon production of a special pass which was almost unobtainable. A local belief, not discouraged, was that a great shaft was being dug from which tunnels were to be driven right under Germany.

The men knew, of course, that some sort of machine was awaited and rumours ran around. It could climb trees, cross rivers and jump like a kangaroo. The camp opened in June, 1916. Weeks passed before the first arrivals, for there had been labour troubles and shortages of everything. So scanty were the supplies of 6-pdr shells that 25,000 had had to be bought from Japan. Then, at dead of night, they heard the sound of engines and rushed out to look. Some ‘Willies’ had arrived and serious training could begin.

Seldom have men been so dedicated to a new thing. The tanks broke down regularly, but this was regarded merely as an agreeable chance to try out their knowledge of the mechanisms. There were nothing like enough to go round and men queued for their turns to drive and shoot. Swinton’s famous Memorandum of February, 1916, was their vade-mecum. Notes On The Employment Of Tanks was very firm on one point. ‘Surprise cannot be repeated. It follows … that these machines should not be used in driblets (for instance as they may be produced) but that the fact of their existence should be kept as secret as possible until the whole are ready to be launched, together with the infantry assault, in one great combined operation’. This is exactly what did not happen. Swinton’s Notes mark the beginning of the great divide, between the men who produced the tanks and those who were to command them in battle: it lasted throughout the rest of the war.

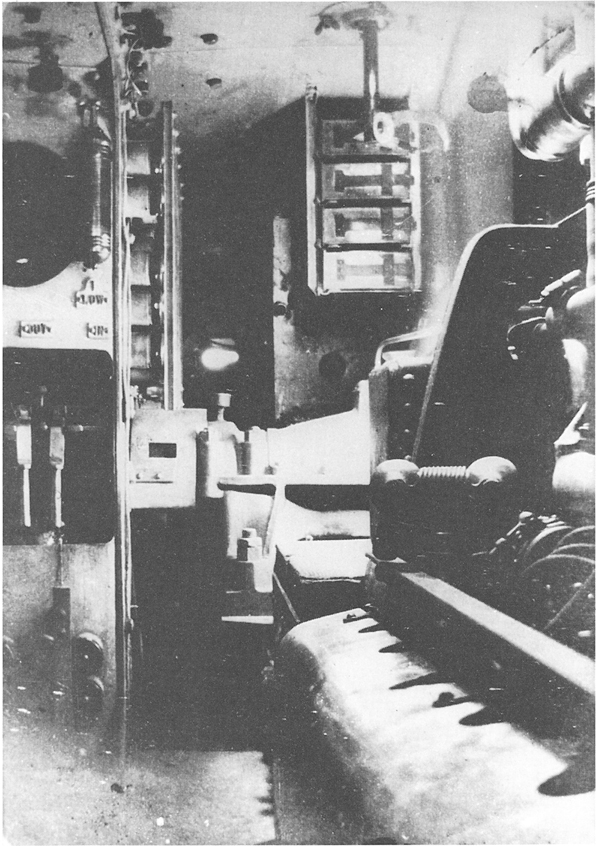

It has to be said that the few weeks of training at Thetford were elementary; it could hardly have been otherwise. The first business of a tank crew is, rather obviously, to keep the machine moving. To keep it moving in the right direction is almost as important. The course at Thetford was nearer to reality than Lord Salisbury’s golf course had been but it gave little idea of what lay in store. Map reading and compass work were hardly touched on and signalling not mentioned at all. Nor was any consideration given to Staff work. Operation Orders for a Division are long and complicated. The commanders of its component parts needed to be practised in extracting such portions of the Order as concerned them and making their own dispositions for carrying them out. None of the crews had had the smallest experience of any serviceable kind. Few had ever been out of England, hardly any had ever seen battle; most had never seen anything more frightening than a Regimental Guest Night or wounds more hideous than a cut finger. The sheer noise, the smoke, the stench and the fog of war were only dimly understood from Bairnsfather cartoons and the like. The fact that, as Weekly Tank Notes put it, ‘except for a few small breaks, a man could have walked by trench, had he wished to, from Nieuport almost into Switzerland’ seemed picturesque but little else. Nobody should be criticized for this. There is high authority for saying that when the blind lead the blind they shall both fall into the same ditch. This happened.

The Somme had been planned as a gunner’s show piece. At long last the British Army had what seemed a sufficient artillery and it set to work to blast the Germans off the face of the earth, wire, machine guns and all. The Germans, well knowing this, dug. Cyril Falls, who walked in the ruins of Thiepval after it had finally been taken, told of ‘underground refuges, some two stories deep, fitted with bunks, tables and chairs and lit by electricity: stocks of canned meat, sardines, cigars and thousands of bottles of beer’.

The artillery, despite enormous effort, failed. Much of the ammunition bought in America was defective and, even more important, the sensitive 106 fuse was not yet in service. ‘Dud’ shells lay everywhere and infantry casualties mounted to figures that staggered belief. From the dreadful 1 July the battle raged on throughout the summer. The pressure had been taken off Verdun, it is true, but other advantages gained, if there were any, had been bought at an impossible price. By the end of the first month it seemed that anything must be tried which had the smallest chance of stopping the slaughter while keeping up the momentum of the attack.

Stern now found himself in a position of great difficulty. As the batteries were moving up for the opening bombardment he had been working with General du Cane on one of Wilson’s new designs, this time for a tank capable of carrying a 60-pdr medium gun. The main object of this was to find work for factories which had completed the first order and saw no signs of any others coming in. On 19 June experiments had been carried out at Shoeburyness and, as Wilson says elsewhere, they had proved the idea to be entirely sound. Mr Lloyd George was convinced and ordered that fifty be built. All tanks, incidentally, were to be camouflaged with the dazzle painting used on ships and the task was given to a Sapper officer, Lieut-Colonel Solomon J. Solomon, the only man entitled to the suffixes RE and RA, for he was an Academician. It was also at this time that Stern met Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who had been conducting a vigorous Press campaign for body armour. Stern was bidden by the Minister, Mr Montagu, to let him into the great secret. He was enthusiastic about it, but doubted the validity of Stern’s idea for using large numbers in a surprise attack. After Cambrai he ate his words handsomely. On 10 July General Burnett Stuart wrote from GHQ asking that twenty existing machines should be sent to France in order to make it possible to decide whether it was worth persevering with them. Stern passed the letter to Swinton who replied that it was essential to keep going. ‘The absolute continuity of supply is, as a matter of fact, already broken but so far the skilled men have not been dispersed.’

At about the time that the demand for tanks to be sent to France came the friendship between Stern and Wilson broke up. The Committee was behaving very tiresomely, demanding that every piffling detail be put before it for a decision, even though the technical knowledge of some members was scanty. The day came when Stern had had enough. At a meeting in July he demanded that this be stopped as it was not merely irritating but a brake on production. His proposition, that the status of the Committee be reduced to an advisory one was, he says, ‘carried unanimously’. Wilson, who was there, put it differently. ‘Such pandemonium reigned owing to the Chairman’s (General Scott-Moncrieff’s) attitude to Col Swinton that any resolution might have been recorded.’ The one that found its way on to the record eliminated the Supply Committee and appointed Stern Director of the Tank Supply Department with Norman Holden, an officer still recovering from his Gallipoli wounds, as his assistant. With all powers and duties vested in him, Stern picked a quarrel with Wilson. Exactly how they got across each other is not clear, but Stern was the entrepreneur who demanded quick results, whereas the other man was the professional who refused to be hurried or to accept anything slapdash. Early in July, 1916, he had sent Stern a report complaining of bad workmanship in a number of places: ‘I do not approve of the work being done at Lincoln and must repudiate any responsibility for it,’ he said. Stern wrote back, not unreasonably, pointing out that the responsibility was Wilson’s and he could not avoid it, adding that ‘these machines are not for peace wear but are rush orders for warfare’. On 17 July he wrote again that ‘I have made many complaints about the quality of the work … Lives will be risked in these machines and it is no argument in excuse for bad or careless work to say that it is alright for trial machines’. The quarrel between the two men erupted on 14 August. In a routine report on a piece of equipment Wilson ended by saying that he would like a decision of the Committee. Stern sent for him and gave a direct order that the words be altered to ‘your decision’. Since he had by then been appointed Director of the Tank Supply Department and the Committee was only an advisory body he was probably strictly correct, though pettiness of this kind was not his usual style. Wilson, much angered, demanded the order in writing, something that every officer is entitled to do when faced with what he considers an improper command. Stern sent for Lieut Anderson as a witness and, says Wilson, ‘I was told to leave the room’.

The unattractive scene demonstrates as nothing else could the strain under which men were working. Wilson cannot have enjoyed speaking ill of his friend Tritton. Stern at another time would not have treated so senior a man as if he had been a clerk caught with his hand in the till. The tanks were needed in France and both men were working themselves into the ground to see that they arrived there. Both were apprehensive about what would happen to them. It is hardly remarkable that something snapped. Unfortunately it was more than a fire of straw. The happy days of the White Hart were never to come again and other quarrels were to follow. It is too easy to call such displays of temper childish, for most people today simply do not understand the feelings of those active during the summer of 1916. The present writer’s father, the least imaginative of men, once told him of how, waiting to go over the bags with his platoon and half-deafened by the guns, ‘I seriously thought for a few seconds, “This must be the end of the world”’. Minds were stretched to a point beyond what would be considered possible in peacetime, for what was seen as the decisive battle upon which the fate of the Allies hung was being fought. Our history was these mens’ immediate future and it is not seemly to blame any of them for behaving out of character.

When the order to send tanks to France arrived at the end of July Stern came near to losing his temper. The machines were nowhere near ready, stocks of spare parts hardly existed and crews had only had an elementary training. Furthermore the whole tank concept was based upon the use of masses of machines at a time when all the preparations for a great armoured attack had been completed. Enquiries at the Repair Shop Unit in Thetford told him of most of the deficiencies. The machinery and skill for taking off tracks simply did not then exist. Two months’ work for the infant Corps lay ahead if the order was to be obeyed. Stern descended upon everybody in authority, from the Prime Minister to the CIGS, Sir William Robertson. They persuaded him to agree that every available machine should be made ready within ten days. No suggestion seems to have been made that they should be pitched straight into the battle.

To make this promise good demanded more than Thetford could offer. Stern went instead to Birmingham, to the Metropolitan Carriage Company which was the biggest single manufacturer of tanks. There he asked for volunteers to come to Thetford and do what was necessary. Forty good men turned out, led by Mr Wirrick of the Company. The Army refused to house or feed a bunch of civilians. At Stern’s urgent request the Chief Constable found billets and the Great Eastern Railway provided a restaurant car. There are so many dismal stories about wartime strikes that it is a pleasure to quote Stern’s words about the men of Birmingham: ‘This is only one of the instances of the magnificent patriotism and unselfishness of the industrial workers, who were ready to labour night and day for the Tanks, from the making of the first experimental machine until the Armistice was signed in November, 1918’.

Sir William Robertson mentions it nowhere in his published writings but he had allowed the idea to get about that he wanted to use the tanks at the earliest possible moment, no matter what their state of battle-worthiness might be. Stern, who missed very little, spoke with d’Eyncourt (now Chief Adviser to the Tank Supply Department) and together they descended upon ‘Wullie’ at the War Office. The CIGS was not a happy man. When Kitchener had been Secretary of State it had been the duty of his old enemy Lord Curzon to oppose everything he said or did. Most of Kitchener’s Memoranda for the Cabinet, whether on the state of the war, the evacuation of Gallipoli, conscription or anything else, have attached to them long and windy papers initialled ‘C of K’ flatly contradicting almost everything. Now the enemy was the Minister, for ‘Wullie’ Robertson and David Lloyd George, in the words of the song, ‘thought nowt of each other at all’. Lloyd George was of Swinton’s mind about not revealing the secret until plenty of tanks were ready. Stern and d’Eyncourt took the same view. Together they urged that ‘the tanks should not be used until they were ready in great numbers. We urged him to wait until the Spring of 1917, when large numbers would be ready’. ‘Wullie’s’ reply is not on record. It was probably his customary grunt. He did, however, agree to the placing of an order for 150 new tanks.

On 3 August Stern put it into writing, addressed to his masters at the Ministry of Munitions: ‘I beg to refer to our conversation regarding the order for 150 Tanks. My Department was originally given an order to produced 150 Tanks with necessary spares, and I was under the impression that these would not be used until the order had been completed, therefore the spares would not, in the ordinary way, be available until the 150 machines were completed. From the conversations I have had with Mr Lloyd George and General Sir William Robertson, and information received from Colonel Swinton, I believe it is intended to send small numbers of these machines out at the earliest possible date, and I beg to inform you that the machines cannot be equipped to my satisfaction before the 1st of September. I have therefore made arrangements that the 100 machines shall be completed in every detail, together with the necessary spares, by the 1st of September. This is from the designer’s and manufacturer’s point of view, which I represent. I may add that in my opinion the sending out of partially equipped machines, as now suggested, is courting disaster.’ The French, who were themselves into the early stages of the tank business, also begged for delay until all was ready. Stern was not being entirely candid. The first fifty tanks were being finished off by the men at Thetford as he wrote.

These were strong arguments. Equally strong were those of the men in France. The end of the battle was nowhere in sight; winter was not all that far off; if winter came before any substantial success had been won – as it probably would – the morale of even this Army, the finest ever assembled, must inevitably fall off. ‘The slightest holding back of any of our resources might, at the critical moment, make the difference between defeat and victory,’ they were told. Stern and the others could not stand out against these urgings. Tremendous events which might shape the history of the world for years to come trembled in the balance. Perhaps it was their duty to let the tanks, with all their imperfections, at least have a try. In any event once they were in France it would be up to GHQ.

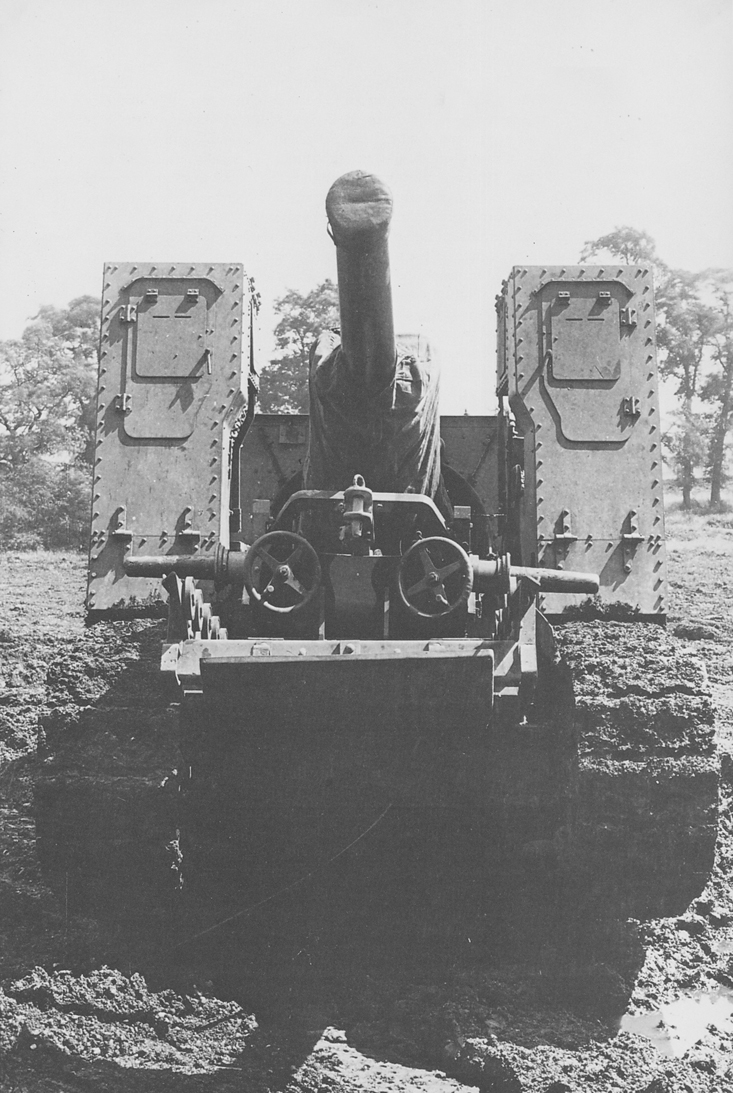

On 15 August, 1916, thirteen tanks of C and D Companies, their sponsons unbolted and carried on specially made trollies, travelled by train from Thetford to Avonmouth from whence they sailed to Havre. It was a back-breaking business, for each sponson with its gun weighed some 35 cwt and the only machinery available to move them was a girder with block and tackle. Between Thetford and the temporary base at Yvrench near Abbeville they had to be loaded and unloaded five times. By the end of the month fifty Mk 1 tanks were assembled in France along with their unpractised crews to await whatever might be in store for them. Wilson, to his intense anger, was not allowed to go with them. When he wrote to Stern asking for more information he received a reply that would have justified knocking the writer down. Everything to do with tanks ‘is entirely under my control and whatever I think necessary will be done … I will arrange for all useful information to be passed on to you. You should not give orders.’ Tritton, being a mere civilian, was told to stay at home. According to Wilson Major Sommers, who commanded the first Company to go, and Major Knothe with the workshop staff, were delayed in England – he does not say why – and arrived in France only on 12 September, three days before the battle. Again it is Wilson who asserts that if it had not been for these two officers ‘the tank would have died on the Somme’. Ten days after the battle had come to an end permission was granted for Wilson to go and find out what had happened to the tanks that were so largely his creation.

In spite of all these things a demonstration was mounted on 26 August for the edification of Sir Douglas Haig and Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding Fourth Army. Five dazzle-painted tanks accompanied by a battalion of infantry put on a brave show. Sir Douglas wrote of it that ‘The tanks crossed ditches and parapets, representing the several lines of a defensive position with the greatest ease and one entered a wood which was made to represent a “strong-point” and easily “walked over” fair-sized trees of six inches diameter! Altogether the demonstration was quite encouraging, but we require to clear our ideas as to the tactical handling of these machines.’ In the published part of his diaries Haig tells of the various conferences he attended during the next couple of weeks and of the plans made there for renewal of the attack. No mention anywhere is made of the tanks or of how he planned to use them.

On 10 September, 1916, the first fifty moved up to the forward area, by train to the Loop, near Bray, a couple of miles from the river and thence across country. Aerial photographs of enemy positions, common coinage to the rest of the army but new and barely comprehensible to the tank men, were produced and pored over. Anti-bombing nets were slung over the tops, spares, pigeons in baskets, signal lamps and two days’ rations stowed away, while the crews were issued with leather anti-bruise helmets. Each ‘male’ tank – the slightly larger one equipped with 6-pdrs – carried 324 gun rounds and 6,300 of SAA. The ‘female’ – designed for trench clearing – had no less than 31,000 rounds for the machine-guns crammed away in the poky inside. Nobody, even now, had more than the roughest idea of what they would be expected to do. The guns on both sides continued to roar, the shell craters grew more and bigger. Four miles of devastated land, far worse than anything that could have been imagined, had to be traversed before they could begin to come to grips with their enemy.

Charteris, who had every reason to know, says that the secret had not been as well kept as people thought. A demonstration attended by a number of MPs, as well as other people, had been followed by letters to neutral countries which had certainly given the Germans cause to realize that something was up. They would pretty certainly have known all there was to know well before the Spring of 1917 and anti-tank weapons could be made far more quickly than tanks. It was possible that even now they were expected.

Under these less than perfect conditions the Heavy Branch, Machine Gun Corps, made ready for its first battle.