NOW CAME THE INQUEST. Stern, in his capacity of coroner, set out for France on the morning of 15 September. Already he was in a vile temper, the result of another brush with authority. Just as he had been about to leave, a civil servant had arrived bearing a message. The Tank Supply Department, being now of no importance, was to give up its office and move all its rubbish to a small flat in a back street opposite the Metropole Hotel in Northumberland Avenue. Today was Friday; everything must be out by Sunday. Stern, whose state of mind as he waited for news of the debut of his tanks can be imagined without a lot of difficulty, exploded. Addressing the Assistant Secretary as if he had been a customer of ill-repute asking for a bigger overdraft, he spoke. His Department was concerned with matters of the highest national importance; not only did it refuse to move, it required a very large building of its own. To avoid any possibility of misunderstanding, an officer of Squadron 20 was ordered to maintain an armed guard over the office during the Director’s absence. Should any attempt be made to enter the place the Assistant Secretary was to be put under close arrest, taken to the Squadron HQ at Wembley and tied to a stake for twenty-four hours. A full account of the proceedings would then be sent to every editor in Fleet Street.

That done, Stern left Charing Cross and arrived in France the next day. There he met Colonel Elles and was told of the events of the 15th. Elles appeared well pleased, but not everybody else shared his feelings. Sir Henry Rawlinson had written a long letter to Lord Derby at the War Office; he gave a thorough exegesis of what had happened on the fronts of the various Corps engaged without mentioning tanks at all. At the end of the letter, as a kind of coda, he spoke of them: ‘The tanks in certain circumstances, such as at Flers and Martinpuich, rendered very valuable service, but they failed to have that effect on the fighting which many of their strongest advocates expected. They laboured under great difficulties. The officers and men who were driving them had not been under fire before; they had had great difficulty in maintaining their direction, owing to their limited vision; and their very low speed over ground torn by shells was a very serious handicap.… Until they have more engine power, can maintain a speed of four miles an hour over really bad ground, and until the personnel has had more experience, they will not be of much value to an infantry assault.’ He then turned to the more important subject of artillery.

That sound judge of the new warfare Christopher Baker-Carr had had more time than the Army Commander to think the matter through. ‘Two facts emerge from the long tale of mishaps and misadventures which had taken place. The first, and one which was completely ignored by the British High Command, was the moral effect on the Germans.… Not only did captured officers and men admit that they felt absolutely helpless when attacked by tanks, but the German official Press lost no time in proclaiming to the world the inhumanity of the British in employing “these cruel and barbarous weapons”. Our friends, the enemy, always “squealed” when frightened, but the reason for this particular paroxysm of righteous indignation appears to have been overlooked by GHQ. The second fact which strikes the observer is that if one or two of the new machines were capable of achieving a great success, there should be no reason why, given good organization and favourable conditions, the large majority should not achieve equally good results.’ Baker-Carr was ordered to put in a detailed report. He dealt fairly and faithfully with the business, tank by tank, and ended with the assertion that, given more reliable and less complicated machines, the tank, ‘under favourable conditions and given suitable organization, would prove to be of inestimable assistance to breaking the deadlock on the Western Front’. As usual he was reviled for his pains.

Not, however, by Sir Douglas Haig. On Sunday 17 September Swinton and Stern presented themselves at Montreuil to pay a call on General Butler. As they waited outside his office the Chief himself appeared and called them to him. ‘We have had the greatest victory since the Battle of the Marne. We have taken more prisoners and more territory with comparatively few casualties. This is due to the Tanks. Wherever the Tanks advanced we took our objectives, and where they did not advance we failed to take our objectives. Colonel Swinton, you shall be head of the Tank Corps: Major Stern, you shall be head of the construction of Tanks. Go back and make as many Tanks as you can. We thank you.’ When d’Eyncourt arrived a few days later and a further audience was granted this had been watered down a little: ‘Go home and build as many Tanks as you can, subject to not interfering with the output of aircraft and of railway trucks and locomotives, of which we are in great need.’

The bull market for Tanks at GHQ was by no means universal at the next stratum down. Amongst the Corps Commanders, Pulteney, a very experienced General who had been in every battle since the beginning, had personally over-ruled the commander of 47th Division over the tank part in the attack on High Wood. Major-General Barter had accepted the tank subaltern’s statement that the tree stumps of the wood itself made an obstacle that his machines could not cross; another route must be found. The Corps artillery said equally firmly that this would ruin their carefully worked-out barrage programme. General Pulteney preferred known to unknown quantities, and who can blame him? The result, of course, was that all the tanks became firmly stuck long before they could do anything useful. General Horne left XIV Corps shortly afterwards, to succeed Sir Charles Monro in command of First Army. His successor, ‘Sandy’ du Cane, knew little about Tanks. Lord Cavan, at XV Corps, had not seen enough to make a convert of him. And of the Divisional Generals only Lawford of the 41st could be reckoned a friend.

From inside the tanks themselves had come a number of lessons. Not only had Charteris had a point in saying that the Germans might have armour-piercing bullets but the invulnerability to small-arms fire had been exaggerated. Fragments of lead from squashed nickel-jacketed rounds (‘splash’ in the vernacular) that had hit the armour mysteriously found their way inside through the tiniest of orifices. In addition to that, bursts of fire from machine-guns had a way of detaching minute fragments of steel from the inner faces of the armour plate, fragments that ricochetted around inside and were capable of blinding a man. The exhausts were a great source of weakness, running up from inside and along the top. The low-grade petrol on issue made smoke, the pipes became red-hot and the noise was abominable. Some crews made make-shift silencers out of biscuit tins; others covered the pipes with layers of the one commodity that was available in quantity, mud. The 8-foot-long 6-pdrs had a way of digging themselves into the ground, should the tank go nose down; they needed to be truncated. The open-trough lubrication system was wretched, but there was no obvious way of bettering it. The improved Creeping Grip slid happily round in mud giving no forward movement; an easy amelioration was the provision of ‘spuds’ on the tracks, protruding metal bars that served as do studs on a football boot. Above all some means must be provided of helping a crew to unditch. It was absurd to have so powerful a weapon kept out of battle when by sweat and ingenuity it might be got on the move again. Some sort of stout bar fastened to the tracks athwartships on top of the tank might work. It would be carried down by the tracks under the belly where it might serve to give enough lift to get the tank out of its hole. It might equally well wrench the tracks off; experiment was needed. The trailing wheels were, everybody agreed, quite needless and a nuisance.

Though Stern had fiercely opposed the use of his tanks before they were ready, he was reasonably well satisfied with the results. He visited the Railway Loop near Bray where the survivors of the battle had gathered along with the newer arrivals and had a word with his brother in the Yeomanry who, like the rest of the cavalry, was glumly leading his horse home again. Next morning, with Swinton and General Butler, he set out for Paris by road to visit Colonel Estienne to find out what the French were doing in the matter of armoured fighting machines. The first of them had just arrived at Marly and Stern was invited to come and look at it.

Estienne was, as near as no matter, the French equivalent of Colonel Swinton, with M le Breton for his Wilson. His ideas were in advance of his time, for Estienne was not thinking in terms of mechanical pill-boxes but of mechanized cavalry. He wanted lots of little tanks, little tanks that could be brought to the edge of the battlefield in the backs of lorries. Already he had tried something like ‘Little Willie’ with the original St Chamond, but it had shown all of ‘Little Willie’s’ failings. He therefore turned to M Louis Renault, the best man by far for his purpose. At the time of his meeting with Stern, however, French development lagged rather a long way behind. For immediate purposes there was no tank superior to the Tritton-Wilsons.

Swinton and Stern were very busy during the last days of September. On the 19th they returned to London and next morning there was a meeting at the War Office. Mr Lloyd George was there, along with Dr Addison for the Ministry of Munitions and Generals Butler and Whigham. It must have been painful for Mr Lloyd George to find himself and Sir Douglas Haig in such perfect accord, for Butler demanded, on behalf of his Chief, that 1,000 tanks be put in hand at once. This was agreed, although it demanded 30,000 tons of steel, 1,000 6-pdr guns and 6,000 machine-guns. Orders were placed, but orders did not mean that the tanks would appear.

On the 23rd Stern set off again for Paris, this time with a large party of experts. D’Eyncourt, Wilson and Tritton were there, along with representatives of the manufacturers and Mr Searle of the Daimler Company. On the same day Stern had been promoted Lieut-Colonel, possibly to put him on an equal footing with the Frenchman. They visited the Schneider factory at St Ouen where a sizeable tank was being built and discussed the St Chamond with the designers. The only common language, for most of them, was German. It goes to show what a hold Germany had in what we would now call ‘advanced technology’. America still lagged far behind in many things.

Wilson examined everything with an engineer’s care, interesting himself particularly in gear-boxes and transmissions. He did not reckon much of what he was shown. Already he was working in a pencil-stub and back-of-envelope way on an entirely new system of his own.

The party was back in London on 28 September. The Assistant Secretary had acknowledged defeat and the Tank Supply Committee had been given new offices at 14, 17 and 18 Cockspur Street. Before long even these proved too small. The thought in front of the minds of the English contingent was, inevitably, engines. If they had hoped to get something more powerful from the French they had been disappointed. Stern’s men ransacked the American factories but found nothing. On 16 October, no new design for the projected 1,000 having been settled, orders were placed, just to keep the factories going, for 100 more Mk 1s.

Though Mr Lloyd George was present at at least three meetings attended by Stern there is no record amongst the latter’s papers of any controversy about whether or not the tanks should have been used at all. Both Mr Lloyd George and Mr Churchill in their own writings are bitter about what they considered the throwing away of a great and secret weapon for very small advantages. The argument has been rumbling on ever since that long-ago 15 September. Broadly speaking, the parties fall into two clearly definable groups – those who say the tank ought to have been kept secret until enough were present to make it decisive include all, or nearly all, the men whose duties about the business were performed in England: those who demanded its use were the men in the field. Before 15 September they had tried everything they could think of to break the German front, including Rawlinson’s dawn attack with four divisions on 14 July. Only this trick remained, and the use by the Germans of armour-piercing bullets suggests that Charteris had a point and the great secret was not all that secret. Baker-Carr puts it crisply: ‘There are exactly two people to whose views it is worth listening, those of Hugh Elles the first commander of the Tank Corps and Colonel J. F. C. Fuller, the first Chief General Staff Officer of the Tank Corps and probably the most brilliant thinker in the British Army today (1930). These two officers, both of whom had to deal not only with the Germans but with (a far more difficult business) the British, were definitely convinced that the benefits derived from the lessons learnt in battle more than compensated for the obvious disadvantage of “premature disclosure”. The very secrecy, which was essential during the embryo period, militated against the highest standard of mechanical and personal efficiency. Everybody was groping more or less in the dark. Even Swinton … was of necessity unfamiliar with the actual battlefields on which the tanks would be called upon to fight.’ The worst aspect of this difference of opinion, sometimes intemperately expressed on both sides, was that it marked the opening up of a gulf, sometimes an abyss, between the men at home who designed and made the machines and those across the Channel whose business it was to command and fight them. Voltaire said it all, with ‘Le mieux est l’ennemi du bien’. In other words is an indifferent tank today more worth having than a better one six months hence? The question is, of course, purely rhetorical, but attempts to answer it were to cause the most serious trouble before the end came.

One ancestor, momentarily neglected, was brought back by Stern. Mr H. G. Wells was invited to visit a factory at Birmingham and to write something about it. He gave full value. ‘I saw other things that day at X. The Tank is only a beginning” in a new phase of warfare. Of these other things I may only write in the most general terms. But though Tanks and their collaterals are being made upon a very considerable scale in X, already I realized as I walked through gigantic forges as high and marvellous as cathedrals, and from workshed to workshed where gun-carriages, ammunition carts and a hundred other such things were flowing into existence with the swelling abundance of a river that flows out of a gorge, that as the demand for the new developments grew clear and strong, the resources of Britain are capable still of a tremendous response.’

Tanks under construction at the Metropolitan Carriage Co.’s Birmingham works.

A few days later Stern received an official instruction from the Army Council cancelling the order for the 1,000 tanks. The fact that the ukase came from Sir William Robertson was all that it needed to raise Stern’s temper to boiling point. He had put up with a great deal from Generals and the end was by no means yet. In May, 1918, he was to write a paper for the then Prime Minister, Mr Lloyd George, which included the words ‘The programme for 1917 was muddled away’. This manifestation of it was not to be endured and, with his customary contempt for usual channels, he went straight to his old friend who was, of course, still Robertson’s Minister. ‘I told him that I had, with enormous difficulty, started swinging this huge weight, and that I could not possibly stop it now. I told him that he could cancel my appointment, but he could not possibly get me to cancel the orders I had placed.’ Mr Lloyd George was equally furious. ‘When I was Secretary of State for War in September, 1916, I ordered 1,000 tanks to be manufactured. Sir William Robertson countermanded the order without my knowledge. Thanks to Sir Albert Stern (his knighthood, in 1916, was still in the future) I discovered this countermand in time, and gave peremptory instructions that the manufacture should be proceeded with and that the utmost diligence should be used in executing the order.’ Stern had to explain in Robertson’s presence what had happened and then tactfully withdrew. It is hard to understand what ‘Wullie’ was playing at. Mr Lloyd George, as well as being the responsible Minister, was President of the Army Council. If ‘Wullie’ thought he could sneak the business through he did not know Bertie Stern. Lieutenant-Colonels at the War Office were ten a penny, but this one was no ordinary middle-piece officer. The arbiters of the destinies of mechanical warfare were no longer friends of the tank. Even Butler, who claimed to be an enthusiast, was a secret enemy of Stern, as later events were to show.

The name of the Tank Supply Department was now dropped and Stern became Director-General of the Department of Mechanical War Supply, with Bussell, an Admiralty civil servant, and Captain Holden as his Deputies. It was a distinction without a difference. The War Office remained the customer and the Ministry of Munitions the shop. Tritton got a well-deserved knighthood early in 1917 but, though Stern tried very hard on his behalf, Wilson got nothing. Later he was given a CMG, the reward of the rear-rank diplomat. Stern pointed out in a letter that, in addition to being the technical brain behind the tank, Wilson had given up a lucrative engineering career for the pittance paid to a junior officer. The answer came back from the Admiralty on 20 March, 1917, that ‘Sir Edward Carson is of opinion that there is no sufficient reason to give special prominence to Lieut Wilson’s share in the design of the Tank’. He was given a half-promise of consideration for membership of the newly-created and widely despised Order of the British Empire. Wilson disdained money – he could have become a millionaire had he wished it – and had no ambition to become an OBE. Stern was given the more respectable CMG in the same list as Wilson. It probably amused him.

A Mk I Tank ditched.

Major-General Sir Hugh Elles, KCMG, CB, DSO.

Swinton now disappeared from the scene, being posted back to the Committee of Imperial Defence; d’Eyncourt, with a KCB, became Chief Technical Adviser, jointly with Sir Charles Parsons of turbine fame. Tritton was director of Construction and Wilson Director of Engineering. Hugh Elles got the command in France and General Anley, an under-appreciated man who had commanded a Brigade at Mons, took over the tanks at home. It was Anley who moved the Corps from Thetford to an unblasted heath at Wool in Dorset.

Stern was busier than ever. It looked as if he would never get a better engine for his tanks than the converted tractor affair that had been in general use so far. The other great difficulty was the transmission. Here Stern made a false step. He had been much taken by the petrol-electric system used in the French St Chamond machine, ‘for it gave greater ease in changing speed, though at the price of greater weight’. Off his own bat he gave orders to the Daimler Company for the making of 600 sets, even though the thing was untried in England. The last months of 1916 and the first of 1917 were critical for the Heavy Branch. Whatever Sir Douglas might have said, the decisions did not lie with him and the tank had powerful enemies. Every time it seemed that a better engine might be available the Royal Flying Corps staked a claim on it and there was no denying that priority for the RFC came first. All the supplies of aluminium and high-tensile steel were earmarked for the flying service and Daimlers refused point-blank to take on any new designs. They were far too busy with more important customers.

The last public appearance of the tanks before winter closed in came in the middle of November; two of them were put in on the 14th to help with the attack on Beaumont-Hamel. Both got as far as the German front-line trench and there they stuck fast. As their guns were still able to bear they kept up a brisk fire until 400 Germans emerged with their hands up. They were rather an embarrassment until infantry arrived to take them away. Four days later, in the attack on The Triangle, an important lesson in direction-finding was rubbed home. Captain Hotblack, already a name of power in tank circles, had marked out the route overnight with white tape. By morning it was invisible under the snow. Hotblack calmly walked in front, bullets whistling and cracking round him, and led the solitary machine straight on to its first objective. That taken, he repeated the performance until the tank became bogged. Only Hotblack’s nearly miraculous survival had made the task possible. In future a better way would have to be found.

Mr Tritton, meanwhile, had been busy with his drawing instruments. The first design must surely have been influenced by Stern. It was for a huge machine shaped like ‘Mother’ but carrying a dome of armour some two inches thick and driven by a pair of Daimler engines. Its estimated weight was something in the order of a hundred tons. Stern always thought big; in Hitler’s War he spent a lot of time demanding that tankers displacing 100,000 tons be built. The ‘Flying Elephant’, as Tritton’s new brain-child was nicknamed, never got beyond the drawing board. Which is hardly surprising. With the Elephant stillborn, he turned his attention to something entirely his own, a variant on his original trench-crosser. It was not, however, primarily intended to cross trenches, for it was something much lighter and faster than any of ‘Mother’s’ brood. He called it the Chaser, for that was to be its function. The design was not of a rhomboid shape but resembled more closely the tanks of a later day. The tracks went only round the chassis and, as with the Elephant, each had its own engine. The choice fell upon the 50 hp Tylor, a well-tried piece of machinery much used in Army lorries and some LGOC omnibuses. At the rear end stood a small armoured shed from which three light machine-guns poked out. It was to be steered by a wheel, to carry a crew of three, to weigh only 12 tons – half the weight of ‘Mother’ – and it ought to manage a speed of 7 mph in reasonable going. The Chaser would be the new cavalry, not calling for a lot in the way of man-power but capable of moving fairly fast and hitting harder than any number of horsemen could do. Wilson reckoned it ‘a sound job’.

The Heavy Branch had gone into the Somme battles with great reluctance. Only an unwillingness to let down the infantry at a time when they were taking a terrible hammering had persuaded the pioneers to let loose their young men at all on a venture that promised so badly. Nobody needed to be told that the Daimler engine, designed for quite different purposes, was not suitable. As it was the only kind available that was even worth trying they had put up with it despite all shortcomings; search for something better had never ceased but only in October, 1916, did some glimmer of hope appear.

Tritton discovered it, purely by accident. In the course of his pre-war commercial business he had made the acquaintance of a young engineer named Harry Ricardo who had invented a two-stroke motor, named the Dolphin, and had produced a number of them from a small factory at Shoreham. Ricardo, though barely 30, came from a long line of engineers, and was kin to the Ricardos of Gatcombe Park in Gloucestershire. As he himself put it, ‘It had been my good fortune to have been on intimate terms with the petrol engine since its first appearance in England.’ At the beginning of the war Ricardo had worked with Commander Briggs on engines for a flying-boat but Briggs’ untimely death from pneumonia had brought this to an end. It was in the late Spring of 1916 that Tritton, knowing Ricardo to have had experience of railway work, sought him out to advise on a matter relating to the moving of tanks on to the railway trucks that had been designed for them. One thing led to another and Ricardo soon found himself an honorary member of Squadron 20. There he met Stern, whom he soon came greatly to admire, and the rest of the founder-members. In this capacity he attended a trial at Wolverhampton and was shocked at what he found. Apart from its insufficient power, the lubrication of the engine was very faulty; the troughs in which the big-ends dipped failed to produce any oil when cocked up at an angle. The sleeve-valve system furnished no means of spreading oil circumferentially and only by applying oil generously to the outer sleeve could it be prevented from seizing up. This process carried oil into the exhaust port; the consequence was smoke being emitted at all times with dense clouds emerging as soon as the engine was ‘revved’ up after idling. This, of course, made all efforts at concealment futile.

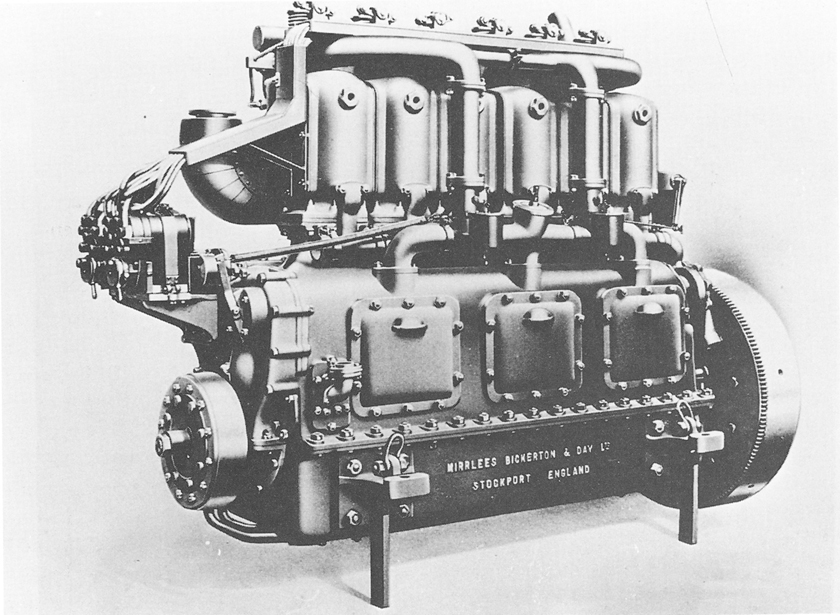

Everybody agreed that a completely new design of engine was needed; this would be easier said than done since all the regular motor manufacturers already had their hands full with work for the RFC on top of the ordinary lorry production. Ricardo, who had many professional friends, was sent to find out what help could be had. The great firms of Mirrlees, Bickerton & Day and Crossley both said that they could make a small number but that somebody else must first design the things. When Ricardo reported back, d’Eyncourt invited him to try his own hand at it. Ricardo was delighted; the subject was his absorbing interest and even though his experience was limited his grasp of mechanical detail was equal to that of any man.

Mr Windeier of Mirrlees lent him two draughtsmen, named Ferguson and Holt, and the three got down to work in the office of Ricardo’s grandfather’s firm. Wilson, the transmission expert, advised that the existing clutches and gearboxes would not be able to cope with anything bigger than 150 hp. The firms approached by Ricardo when the engine design was ready – seven of them in all – said that they could between them put together two or three hundred. By Armistice Day they had made well over 8,000; not all, however, went into tanks.

At the beginning of October, 1916, while a few Mk 1s were still floundering in the Somme marshes, the Mk IV was in existence as a prototype and the Mk V with Wilson’s transmission and Ricardo’s engine was on the drawing-board. Ricardo took a pre-war experimental engine of his own, employing a cross-head type piston which had proved very effective for oil control. The air on its way to the carburettors was made to circulate around the crosshead guides and under the piston crown, raising the air temperature around the carburettor just enough to effect proper carburation of the wretched petrol of about 45 octane that the tanks were obliged to use. By March, 1917, the first engine was running on the test bed. At the end of April Mirrlees had turned out the first production model; so well had his people done their work that it exceeded its designed 150 hp, putting out 168 at its governed speed of 1200 rpm and just over 200 at 1600 rpm. By summer the consortium was making about forty engines each week. Wilson had not yet completed his new gear-box and a few Ricardo engines were therefore put into existing Mk IVs. In the first half of June all the work was finished and the first Mk V was put through its paces at the Dollis Hill testing ground. It worked well, amazingly well considering the shortness of the time given to it. The only complaint was that much of the exhaust was inside the hull and that it grew excessively hot during running. A metal jacket was added and this seemed to work well enough during the routine tests carried out by Squadron 20. Much encouraged, Ricardo set to work on a 225 hp version.

However hopeful things might be looking in the factories and on the testing ground there was little cheer for what was called the Fighting Side in France as winter closed in and the Somme battles petered out. Nor were things going well for Stern. As already mentioned, he had been over-impressed by the petrol-electric system of the St Chamond. As he was not an engineer but possessed of daemonic energy he pushed ahead with other ideas on his own initiative and without the backing of the professional experts. Anything seemed worth trying, however long a shot it might be, for there was always the possibility that something might turn out better than expected. In addition to ordering the Daimler petrol-electric machine he approached Mr Mertz, the greatest authority in this country on electric traction, and demanded an attempt at a better means of propulsion based upon that used by the ordinary London tram. Vickers were pressed into service to build a Williams-Janney hydraulic transmission, the Hele-Shaw Company were told to produce something similar and Metropolitan to make, in addition to Wilson’s gearbox, a multi-clutch device designed by a Mr Wilkins. These side-shows destroyed any chance there might have been of getting back again on good terms with Wilson.

In France the tanks had been removed from the Loop and given a home of their own in and around the empty château of Bermicourt near St Pol. Baker-Carr was invited to take command of one of the new tank battalions about to be formed and, his work with the machine-guns being pretty well finished, he accepted with delight. Elles, a couple of years his junior in the Army List of long ago, had twice formed up to Sir Douglas with the suggestion that Baker-Carr should command the about-to-be-formed Tank Corps with himself as chief staff officer. Sir Douglas, whilst appreciating his motives, was quite firm about it. Lieut-Col Baker-Carr had not been to the Staff College; there was, therefore, no more to be said about it. Baker-Carr, probably rightly, said that it was a good job. His forte was the making of something out of nothing and he was regarded in the higher circles as a buccaneer. Elles was a better organizer and doors at GHQ opened to him which would have been slammed in the face of the other. The two men got on extremely well together. One fortunate result of chivalrous behaviour was that it left the post of Chief of Staff open and the man who above all others was born to fill it happened to be available – Lieut-Col J. F. C. Fuller, commonly called ‘Boney’.

All the same it is interesting to speculate about what might have happened had the command gone to Baker-Carr. Like Elles, he only held the rank of Lieut-Colonel but he was no run-of-the-mill professional field officer. His years in civil life had removed some of the scale that must form over the eyes during the encapsulated life of the regular soldier. Elles was young for his rank and had no particular claim to recognition. Baker-Carr knew, and was known by, all the important men and they had a wholesome respect for his tongue. Wavell, no bad judge, wrote of him as ‘of very independent and outspoken views’. He would have been less trammelled by the fetish of ‘loyalty’, which so often means acquiescing in the decisions of a senior officer even when they are manifestly absurd; and nobody would have dared call him a ‘croaker’, not even ‘Uncle’ Harper. Elles, one may feel, was perhaps too disciplined a man to argue about orders for his tanks whatever his private reservations may have been. But this is, of necessity, speculation.

By November, 1916, the Heavy Branch had acquired some young officers of outstanding merit. Hotblack had given proof of the rarest kind of courage and was to do so over and over again. Captain Giffard le Quesne Martel was another such, but although a DSO and a MC testify to his gallantry it is as a thinker that he is remembered.