THE PAPER, called A Tank Army, was written at Bermicourt in November, 1916, the same month during which Mr Churchill was setting out his own ideas in the more famous thoughts on mechanical warfare, Variants Of The Offensive. Though it went out over one signature the Bermicourt manifesto was actually the work of five thinkers, Elles, Fuller, Hotblack and Uzielli – head of Tank Corps ‘Q’ Branch – in addition to the signatory Martel. They prophesied as the shape of things to come Battle Tanks, Destroyer Tanks, Sapper Tanks and even Ambulance Tanks, all of them rattling along at 20 mph or better. The Battle Tank would carry nothing less than a 12″ howitzer and all would be not merely amphibious but screw-driven for river crossings. Fuller admitted, years later, that it was only done to clear their minds. Some of the prophecies were fulfilled during the prophets’ lifetimes, but Martel, for one, was to modify his ideas as time went by.

While Bermicourt lucubrated, Stern was having his work cut out to keep up supplies even of the outmoded Mk Is. Constant demands from both sides of the Channel for changes in specification, some trivial but others quite important, kept the factories from maintaining the smooth production runs that the builders wanted to see. Squadron 20, still dressed as sailors and technically part of the Naval Air Service, was preserved in existence after the other original Armoured Car Squadrons were disbanded for testing machines as they came out of the factories and for shipping them to France; about half the Squadron became permanently based at Le Havre. The naval antecedents of one early optional extra for tanks suggest that the squadron had some hand in it. All larger warships were equipped with anti-torpedo netting which hung around them as farmers hang netting around their raspberries. The nets were carried outboard and supported on cigar-shaped wooden spars about six feet long; these, some minor genius discovered, could be attached to tank tracks and, thanks to the lozenge shape and lack of turrets, could pass right round the hull and give quite a lot of help when stuck in the mud. They became a standard issue; not an answer, but better than nothing. It was as well for the Heavy Branch that there was a lapse of months after Beaumont-Hamel until the next battle. Even if ‘Uncle’ Harper, now commanding 51st (Highland) Division, and his peers did not reckon much of the tanks, men like Hotblack were building up a tremendous esprit de corps inside the new arm of the service. Instead of dreaming about tank armies yet to come they trained their new crews extremely hard. Next time it would be different.

Stern went to and fro between London and Bermicourt, with visits to GHQ at Montreuil. He had a little to tell Elles for his comfort, but not much. By the end of November there wre 150 tailless Mk Is in being; the factories were working on 100 more, in addition to fifty of the Mk II, with spuds on the track plates, designed for but not fitted with better armour, and fifty Mk IIIs whose only difference was that the armour was slightly thicker still. The Mk IV, the subject of the 1,000 order, was in plan form. It looked much the same and had – for want of anything else – the same engine but there were important differences. The petrol tank was to be at the back, the shoes wider, the armour better and, above all, the sponsons were to be made so that they could be stowed inboard when travelling by train. Solomon’s glories were abandoned for a mud-brown colour. It had a compensating weakness. Some expert – Stern calls him ‘an officer of the Tank Corps who had once been in charge of the Lewis Gun School at St Omer’ – insisted that the slim and light Hotchkiss gun should be supplanted by the tubby Lewis.

Apart from a bulkiness that limited its ability to traverse and was vulnerable to damage from small arms fire, the Lewis had a drawback that made it quite unsuitable for tanks. The ingenious and effective cooling system relies upon an aluminium radiator casing which maintains a steady flow of air during firing as the gases following the bullet are drawn from rear to front through the flanges. When the rear of the gun is mounted inside a hot, fume-laden tank the process goes into reverse, squirting a stream of burnt cordite gas straight into the gunner’s face. Every tank man learnt this within a minute or so. Stern left it on record that ‘The Tank Corps told us that they could not go into battle with the Lewis gun in the front loophole, and that until we could make the necessary alterations to put back the Hotchkiss gun no Tank actions could be fought’. Nevertheless the Lewis gun remained. One cannot help wondering what Baker-Carr would have done; probably a short drive to Montreuil to get Sir Douglas out of his bath if necessary.

The litany of hopes deferred went on. At the November, 1916, meeting, in the presence of General Davidson from GHQ, General Anley and Elles, Stern announced that the first Mk IV would be ready in January and, if the order were confirmed, the whole lot should be available by September. He then mentioned Tritton’s ‘Chaser’, whose son was to become the famous Whippet. Davidson and Elles liked the idea; Stern asked for a quick decision so that he might order 500 engines. There seems no reason, apart from the usual blowings hot and cold by the War Office, why at any rate some Whippets should not have been at Cambrai. But Cambrai, in November, 1917, was a full year away.

On the last day of 1916 Colonel Elles, no doubt with the benefit of advice from Baker-Carr, Hotblack and Martel, wrote a long minute about the unsatisfactory situation: ‘The fighting organization is under a junior officer who, faute de mieux, has become responsible for initiating all important questions of policy, design, organization and personnel through GHQ France and thence through five different branches at the War Office. In England administrative and training organization are under a senior officer located 130 miles from the War Office (Anley, at Wool) with a junior Staff Officer (Staff Captain) in London to deal with the five branches above mentioned. … In actual fact, the Director-General of Mechanical Warfare Supply, an official of the Ministry of Munitions, at the head of a very energetic body, becomes the head of the whole organization. This officer, owing to his lack of military knowledge, requires and desires guidance, which none of the five departments at the War Office can, and which the GOC Administrative Centre is not in a position to give him. In effect the tail in France is trying to wag a very distant and headless dog in England.’

January, 1917, was a month of great importance for the future of the tank. Stern, as has been mentioned before, had been much attracted by the petrol-electric transmission used by the St Chamond. Back in September, ‘all the experts were against me, but later in the year GHQ made such urgent demands for Tanks that, in order not to lose time, I gave orders to the Daimler Company on January 5th 1917 for 600 sets of petrol-electric gear… The machine had not yet been tested, but this was to prevent any delay should the trial machine be a success.’

It was not. A test was carried out on 12 January ‘and the result clearly showed that the Daimler Petrol Electric was unable to pull out of a shell hole except by a succession of jolts, produced by bringing the brushes back to a neutral position, raising the engine up to 1800 rpm and then suddenly shifting the brushes up to the most advantageous position.… All agreed that it was unsatisfactory. So after a great controversy and many tests the Petrol Electric engine was rejected as untrustworthy and all orders were cancelled.’ Stern came in for bitter criticism from Wilson for having thus disrupted the entire year’s programme. Wilson had been with him in France and had watched the show. His view was uncompromising: ‘The large French machine (petrol-electric) could put up no performance whatever.’ Had this happened a year earlier when Stern and Wilson were still friends the engineer would probably have been able to talk the amateur out of his over-enthusiasm. By December, 1916, however, they were hardly on speaking terms. Wilson seems to have felt that the responsibility lay with the Head of the Department and if he wanted to do something silly he could get on with it. Stern’s cavalier behaviour of the previous summer still rankled.

Later in the same month Elles sent an officer to Stern in order to get firm figures of deliveries of new machines. Stern declined to be drawn; there were, he said, too many imponderables. Though he made no promises, he did give an estimate of twenty to thirty a week after the end of March. GHQ was now pressing for as many tanks as possible before May, adding that ‘almost any design now is better than no tank’. Obviously some new battle was being planned for the Spring. Stern knew nothing of Haig’s intentions but Bermicourt did. Elles sent for Baker-Carr in February and told him that ‘there’s going to be an attack by the Third Army in front of Arras about the 9th or 10th of April’. C and D Battalions, the Somme veterans, were to be made into the First Tank Brigade and Baker-Carr was to command it.

On 3 March, 1917, Stern put on another performance in order to show how much the tank had improved since ‘Mother’s’ first appearance just over a year before. This time it was to be at Oldbury, Birmingham, and once again the arrangements were to be made by Squadron 20, now charged with the testing of every tank before it was shipped to France. About a hundred spectators were invited, including a strong French contingent under General (as he now was) Estienne. Seven machines were to be put through their paces. First came the standard Mk IV, the tank which would win immortality at Cambrai. It was not all that different from ‘Mother’ except for its thicker armour, shorter guns, and sponsons designed to swing inboard for rail travel. Top speed was still no more than 4mph. Next to appear was Tritton’s Chaser, the 12-ton cavalry substitute with a speed of 7½ mph and a single light machine-gun. Wilson says that ‘It put up a fine performance and showed a good turn of speed and quick manoeuvre’. Then came a Mk II fitted with the Williams-Janney hydraulic transmission which did away with the necessity for any clutch or gear-box at all. To quote Wilson again, ‘This machine showed great ease of control, but could not be produced in quantity and developed some faults in continuous running that were not overcome until late in 1917.’ It was not until 1918 that three British tanks, originally Mk IVs, were made to this specification by Brown Bros in Edinburgh; they were not a success.

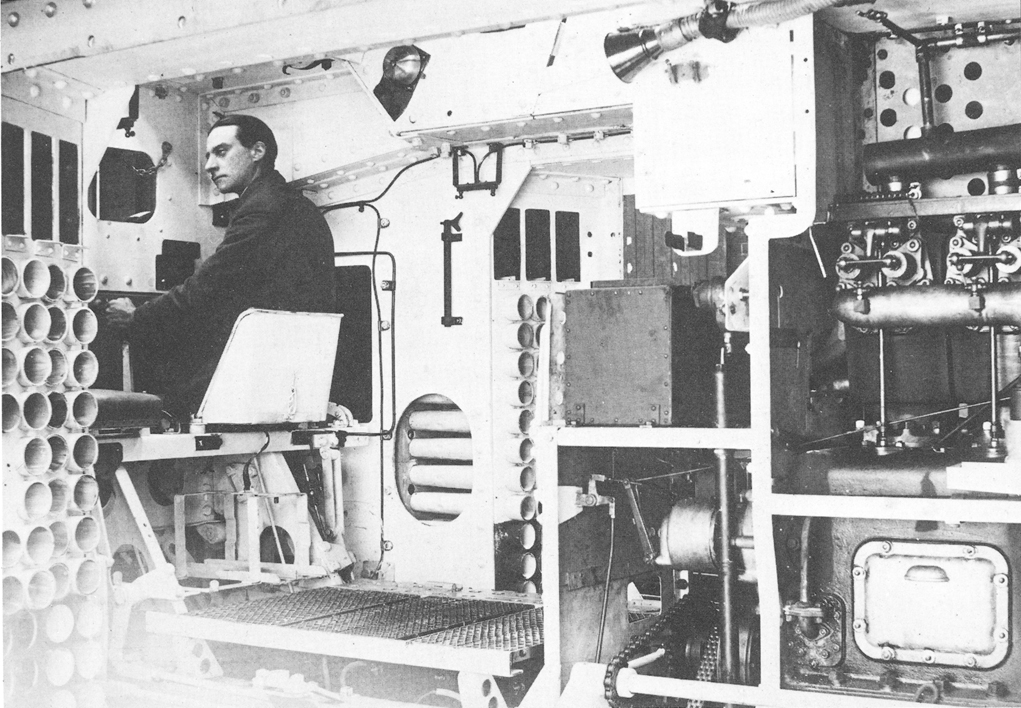

There followed the star of the show, a Mk IV containing Wilson’s greatest gift to mechanized warfare, the epicyclic gear-box. His comments are not vainglorious but strictly factual: ‘It was obvious that this was the most practical solution of the difficulties and this machine ran the remarkable distance of 300 miles on test without serious mechanical trouble. This arrangement was adopted in the Mk V and all subsequent machines.’

The next performer was the one upon which Stern had misguidedly pinned his faith, the Daimler Petrol Electric. The power unit was ‘a six-cylinder Daimler engine fitted with aluminium pistons and a lighter flywheel.’ The transmission was described in the Programme: ‘A single generator coupled direct with the engine supplies current to two motors in series. The independent control of each motor is accomplished by shifting the brushes. Each motor drives through a two-speed gearbox to a worm reduction gear and from thence through a further gear reduction to the sprocket wheels driving the road chain driving wheels. A differential lock is obtained by connecting the two worm wheel shafts to a dog clutch.’ Wilson says dismissively that ‘This machine had not sufficient tractive effort to pull out of shell holes.’

Of the last two competitors one, the Wilkins Multiple Clutch machine, ‘had trouble and did not compete’. Charles Mertz’s entry, the Westinghouse Petrol Electric, ‘put up a good performance but the transmission was so heavy and occupied so much space that it was not a practical proposition.’ Stern’s effort to go it alone had failed. Mention has already been made of the notes made by Wilson in the copy of Stern’s book that he presented to Major Buddicum. One of them, dealing with p. 167, reads thus: ‘The History of design during 1917 is as follows. After the failure of the Daimler Petrol Electric and the cancellation of the 800 order for same (Stern says it was 600) which order was given against the advice of Major Wilson and Mr Tritton, the construction of Mk IV was hurried on; this was undoubtedly right as it was the only machine that could be constructed to be of any value in 1917, but a new design should have been prepared so that construction for 1918 could be commenced in good time.… A machine was designed by the Metropolitan Company embodying Wilson’s epicyclic gear and the above conditions (machine-guns in preference to 6-pdrs). This machine was known as the Mk VI. A machine was also designed on the general lines of Mother, but using the epicyclic gear and other improvements in transmission and tracks and heavier armour. This machine was known as the Mk V. Mock-ups of both these machines were inspected at Birmingham on 23 June and met with general approval. Mk VI was inspected again on 13 July and passed but subsequently Col Stern and Sir Eustace d’Eyncourt expressed their disapproval of both machines and no further work was done on them.’ Wilson does not explain the reason for this sudden condemnation.

‘Requirements were completely changed and the general scheme of a small machine known as Medium B was drawn out and submitted on 30 July. No action was taken until 21 August when Mr Watson was placed in charge of the design of this machine.… Thus we see that in September, 1917, MWD had no designs embodying the improvements dictated by experience ready to place in the hands of the manufacturers. The position was still further complicated in that MWD was torn by internal dissension, the original members of the staff having unfortunately lost that great feeling of respect and admiration for Lieut [sic] Stern’s energy and driving force with which he so inspired them in 1915 and the earlier part of 1916.’ ‘It was under these sad conditions that at last on the 5th October an order was placed with the Metropolitan Company to design under Major Wilson and construct a machine embodying epicyclic control and the 150 hp Ricardo engine, but it was then too late to embody all possible improvements as quantity production had to be commenced as each detail was decided upon, and over £2,000,000 of material ordered before the drawings were complete. … Although the order was only placed on the 5th October, 1917, the first machine was completed in January, 1918. Ten were completed in February and nearly 100 in March. This machine was known as the Mark V and proved of great service in 1918.’ Had the designers and manufacturers been less rushed, a serious defect which will appear later might have been avoided. Stern came in for a lot of blame, but he seems to have been unlucky. He went back to France in April, lunching with Mr Lloyd George at the Crillon, and his diary for the 19th includes an entry saying, ‘Spent Saturday at St Chamond and saw our Tanks, fitted with their petrol-electric transmission, ascend a hill of 55V It looked as if they really did manage some things better in France, but the machine was still not reckoned good enough and was swiftly dropped.

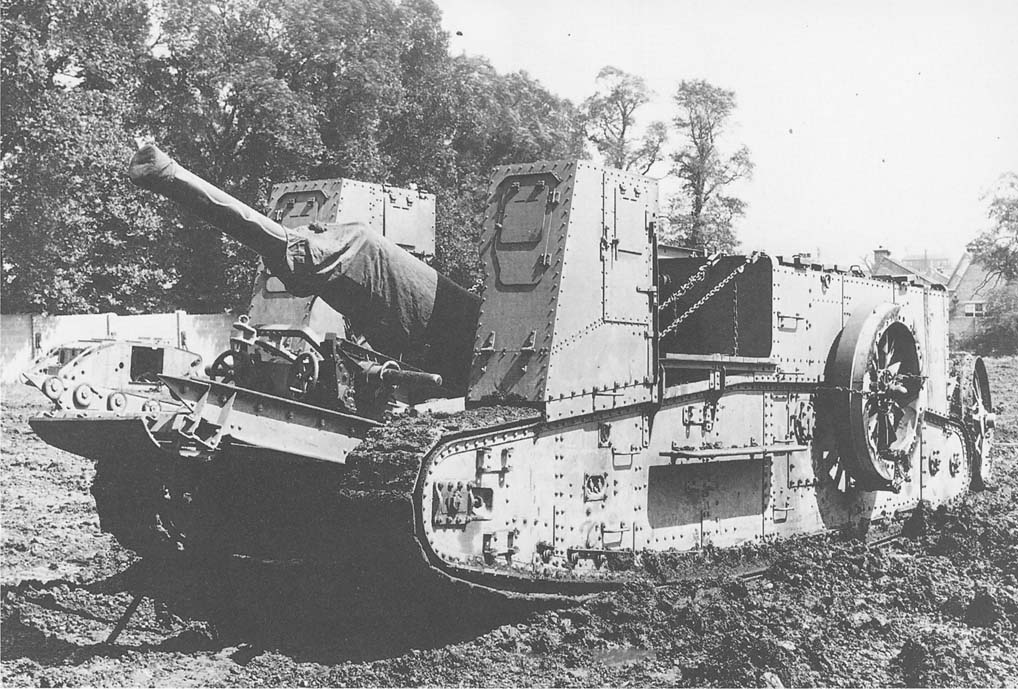

There was yet another lost opportunity. At the demonstration there was shown the first tank designed to carry a field gun or even a medium artillery piece, the model of which fifty had been ordered in June, 1916. Wilson remarks that ‘It is of interest to note that when Major Wilson stated that either a 5-inch 60-pdr or a 6-inch howitzer cold be fired from this machine his assertion was derided by most of the members of the Ordnance Committee but both guns were successfully fired from the machine at Shoeburyness, the amount of movement being accurately forecast in both cases.’ Self-propelled artillery would have been of enormous value during the last battles of 1918; thanks to the unbelievers it was never used. Nor was it in 1940.

Back at Bermicourt, having seen all these shapes of things to come, Colonels Elles, Courage, Hardress-Lloyd and Searle waited for the arrival of some more Mk Is or Mk IIs. It was the best they could hope for and whatever battles were to be fought in the Spring it would be these obsolete machines that would have to lead the way. They were not kept waiting long. The freezing cold and snow of March were followed by the freezing cold and snow of April at about the time the Mk IIs began to arrive. Joy soon gave way to horror. Not only did these lack the promised better armour, they lacked any armour at all. The hulls were of mild steel boilerplate, incapable of keeping out so much as a pistol bullet. Some of the hulls had perforations for the fitting of a second skin at some future time, but this was never done. The explanation was pretty clear. U-boat sinkings had reached proportions that might easily have lost us the war. Every square inch of armour was needed by the Navy to build new fast submarine-killers. Nor was this all. April, 1917, was the worst month of the war for the Royal Flying Corps. Before it was out 151 British machines had fallen to the guns of Germany’s new Albatros and Halberstadt fighters. The RFC, whose pilots had an expectation of life then of twenty-one days, did at least have the consolation of knowing that the SE5 and the Bristol fighter, aircraft that would soon redress the balance, were coming into squadron service. The Heavy Branch seemed to be moving backwards. On the wider stage two events dominated. Russia, if not yet out, was down and only small German forces would henceforth be needed in the East. The strains of ‘Over There’ could, indeed, be detected on the west wind but Uncle Sam was virtually unarmed and his sons untrained. It would be long before they could much affect the military balance.

Rear view of the same, with wheels. These were later removed.

Meanwhile General Robert Nivelle had a plan. His attaque brusquée that had served so well at Verdun was going to be repeated on the grand scale towards the Chemin des Dames. The General had immense confidence in it, a confidence shared by nobody else. The British Army, having narrowly escaped being put under his command, was to contribute with an attack by Allenby’s Third Army. In accordance with French practice exact details of the whole business had been broadcast through the customary network of wives and mistresses of those planning it. The fact that the Germans had withdrawn from the untidy positions which events had forced upon them, as it had also upon the Allies, to a new and carefully prepared trench system called the Hindenburg Line made no difference to Nivelle. Allenby was to strike first, on 9 April, his job being to take the entire line of Vimy Ridge. Sixty tanks, mostly survivors of the Somme plus the bogus Mk IIs which had never been intended for other than training, were to take part.

Unless Stern had greatly deceived himself, the use of these machines showed some lack of honesty at GHQ. On 12 March he had written to Dr Addison that ‘I have persistently opposed the premature employment of Tanks this year. Also the employment of practice Tanks, i.e. Marks I, II and III in action this year. At the War Office Meeting last Sunday General Butler assured me that sixty machines of Mark I, II and III, which are being kept in France ready for action only as a temporary measure and which are really practice machines, will be returned for training purposes as soon as they can be replaced by the delivery of Mark IV machines. I consider it more than unwise to use practice Tanks in action under any circumstances. They have all the faults that necessitated the design of last year being altered.… Their failure will undoubtedly ruin the confidence of the troops in the future of Mechanical Warfare.’ He was right.

Baker-Carr, who accorded Allenby an admiration he withheld from most Generals, was at the pre-battle conference. The tank part in it was necessarily subordinate to that of the traditional arms and once again they were to be employed in small packets. Given the equipment available it could hardly have been otherwise. Allenby took Baker-Carr aside after the others had gone and ‘told me how confident he was that tanks would prove of great value’. Baker-Carr went the rounds of the Divisional Commanders and heard other views: ‘Several seemed to think that tanks could travel at twenty miles an hour and, starting a long way behind the infantry, could catch them up before reaching the first objective.… One of them steadfastly refused to allow a tank to come within a thousand yards of his front line until zero hour, in case the Germans might hear it (amid the roar of a thousand guns, be it remembered) and suspect that an attack was about to be made.’ Baker-Carr affected to agree but arranged that his tanks should actually move at the same time as the infantry. When all was over the General – he is not named – wrote to thank him.

Everything militated against a success for the Heavy Branch. To begin with it rained in torrents and bogged down all the machines waiting in the moat of the old Arras Citadel from which they were due to move off at 5.30 am. The materials ordered for construction of a causeway did not arrive. By superhuman efforts a number of tanks were got on to the start line; then it began to snow. By late morning the last had been extricated and they joined the infantry; this section did very useful work in clearing out German strong-points. Those allotted to the Canadians, however, achieved nothing. The ground leading up to Vimy Ridge was sodden by the rain and not a single tank out of the eight put in an appearance.

There were, however, bright spots. The Mk II tank ‘Lusitania’, commanded by Lieut Weber, having squashed one machine-gun nest, went on towards a German trench closely followed by the infantry; so closely indeed that Weber could not use his 6-pdrs for fear of hitting friends. It did not matter. The moral effect was enough and the occupants emerged with hands above their heads. ‘Lusitania’ then moved on to the Feuchy redoubt which it smashed up with gunfire as the enemy made off. They went to ground in a dug-out by a railway arch with Weber on their heels. Then came an odd incident. With shells, possibly British, falling all round them Weber sensibly decided to move back a little. This involved climbing a steep bank which the over-heated engine refused to take. The crew, drowsy with the fumes of cordite and petrol, took the opportunity of having a quiet sleep in the middle of the battle until the engine had cooled down. As soon as it started ‘Lusitania’ was off again, passing through the infantry, flattening more wire and chasing the garrison from another redoubt. Later in the day the magneto failed; by then it was 9.30 pm and the petrol was nearly exhausted. With shells dropping all around them and machine-gun bullets splashing uncomfortably close, Weber brought his crew out and joined up with the nearest infantry. In the morning he set out alone and returned with a new magneto, to be greeted by a battery commander apologizing for having fatally shelled his tank. So perished ‘Lusitania’. Weber earned his MC and Sergeant Latham his MM.

Baker-Carr had had an abominable day waiting by a telephone for messages that never came or arrived garbled. ‘In the small hours of the morning Elles and Fuller arrived with the appalling news that most of the tanks had got stuck whilst leaving their “lying-up” place. I do not know whether I wept, but I felt like it. It seemed so cruel after all the thought and care that we had lavished on our preparations.’ It was not everywhere a tale of failure. Those messages that got through were for the most part encouraging: ‘We have reached Z22 B64 and are going strong’. ‘Have taken Tilloy village’; ‘900 prisoners scared and starved morale rotten’; a tank named Daphne claimed to have reached the Blue Line. Allenby’s army had won a demonstrable victory and the Heavy Branch had certainly saved many infantry lives. One lesson had been taught: never to take unreconnoitred short cuts, no matter how alluring. One group of six machines made a path of railway sleepers and brushwood in order to circumvent what looked an unsafe way by the Crinchon stream. Underneath and invisible lay a morass into which all of them cascaded. It took many hours of blasphemous work to have them dug out, too late to play the parts given them.

Arras had been rather a poor day for the tanks but two days later came Bullecourt. This time it was the turn of 4th Australian Division to do the dirty work. To make it easier they were given eleven Mk I and II tanks, all of the kind described by Stern as ‘practice’. The infantry commanders, after the last battle, were none too keen about it, for men unaccustomed to tank work had tended to bunch around them and had accordingly drawn very heavy fire upon themselves.

Not a single tank survived the opening attack. Dazzle painting had been abandoned as useless and all were now in the standard mud-brown. Against the snow it showed up admirably, from the standpoint of the German gunners. As they moved slowly forwards nine were picked off almost at once, one of them having come to a halt with clutch trouble. The armour in which they had trusted proved useless. Even small arms fire riddled the hulls. Two more disappeared into the blue heading towards Hendecourt with a party of Australians following behind. Neither tanks nor Diggers were seen again. Two tanks were trooped in slow time through Berlin shortly afterwards and they may have been these. It is hardly wonderful that the Germans were not moved to build tanks for themselves on the evidence of such death-traps. One tank, commanded by Lieut Money, seems to have reached the German wire before a direct hit from a field gun set it ablaze. All the crews who were not too badly wounded did as they always did on these occasions. They took whatever weapons they could find, Lewis guns or even revolvers, and joined up with whoever could make use of them. All the same, when an Australian Brigadier told Major Watson that ‘tanks were no damned use’ he could hardly argue. Still less could he explain how scurvily his Corps had been treated.

The strangest episode of all was at Monchy-le-Preux. The village, on top of a hill, was the target for six tanks in support of the 15th (Scottish) and 37th Divisions who were to move off at 5 am on 11 April. Two tanks broke down in the darkness, one became ditched but the remaining three ploughed on through the snow. Of our infantry there was no sign. As dawn broke and the ungainly shapes presented a perfect target for German gunners the three subalterns conferred. They must go either forward or back and it was surely right to go forward even though alone. The three drove into Monchy, shot their way down its only street and came out at the far end. Germans, seeing them to be unsupported, emerged from their hidey-holes and re-occupied the place. The tanks swung round to face a barrage of small arms fire and were also pelted with grenades. For an hour and a half they fought it out until a barrage came down and knocked out all of them. They were British shells. Nobody had thought to tell the tank commander that the attack had been put back by two hours. The infantry had to make a fresh start and had a hard battle to retake the place. Not to be outdone, a cavalry squadron, kept as usual for the ‘break-through’, staged a knee-to-knee charge. A little barbed wire and a few machine-guns cut them down. Colonel Bulkeley-Johnson was killed. No doubt it was the end he would have wished.

On 3 May came the last stab at the enormously strong Bullecourt position. This time the eight tanks employed all reached their objectives under very heavy fire. It was more than the infantry could manage to follow behind so few machines through such a barrage. One tank was riddled with armour-piercing bullets – it was, apparently, one of the training machines without proper protection – and five of the crew wounded. Five of the six Lewis guns were shattered, their big radiator casings being smashed. The remaining tanks turned round and came home. There was nothing more for them to do. Their brave and resourceful conduct brought the Heavy Branch another Military Cross, a DCM and a Military Medal.

One last, and significant, little action remained before the Arras battles passed into the history books. It happened at Roeux, a couple of miles north of Monchy where there stood a group of ruins called the Chemical Works. Guy Chapman, that fine soldier and writer, watched it. ‘At every other hour, it seemed, a voice from division announced a further attack on the Chemical Works by the Highlanders. Each time they won it, and each time they were driven out. Our line lay waiting for them to finish. Every time they went in, they killed everything that was on the ground and each time, like dragon’s teeth, the enemy sprang up again. The light died away without any alteration in the landscape. It had been another failure.’ The Highlanders were ‘Uncle’ Harper’s 51st Division. Baker-Carr’s account is not quite the same: ‘It was a hard-fought little battle and the infantry commanders were unable to speak too highly of the valuable assistance they received from the tanks. These reports were so eulogistic that I was much amused when the Divisional Commander in his report gave the entire credit of the successful action to the infantry and barely mentioned that fact that a tank had even been present. It was not any lack of generosity that prompted this omission but “Uncle” adored his “Harper’s Duds” and took good care that every single iota of praise should be bestowed upon them.’ The 51st had been at Beaumont-Hamel before moving to the Arras front where they formed the left hand of the British attack; immediately on their own left was 4th Canadian Division. The Canadians complained afterwards that the 51st had failed to keep up with them, save for one platoon. This one remained all day attached to the Canadians while the rest of its brigade stayed in the wrong trench facing the wrong way, insisting all the time that it was in the right trench facing the right way. These things happen. It did not alter the fact that, to ‘Uncle’ Harper, everything 51st – ‘my little fellers’ he called them – did was perfection. Tanks, after what he had seen, were things they would have nothing to do with.

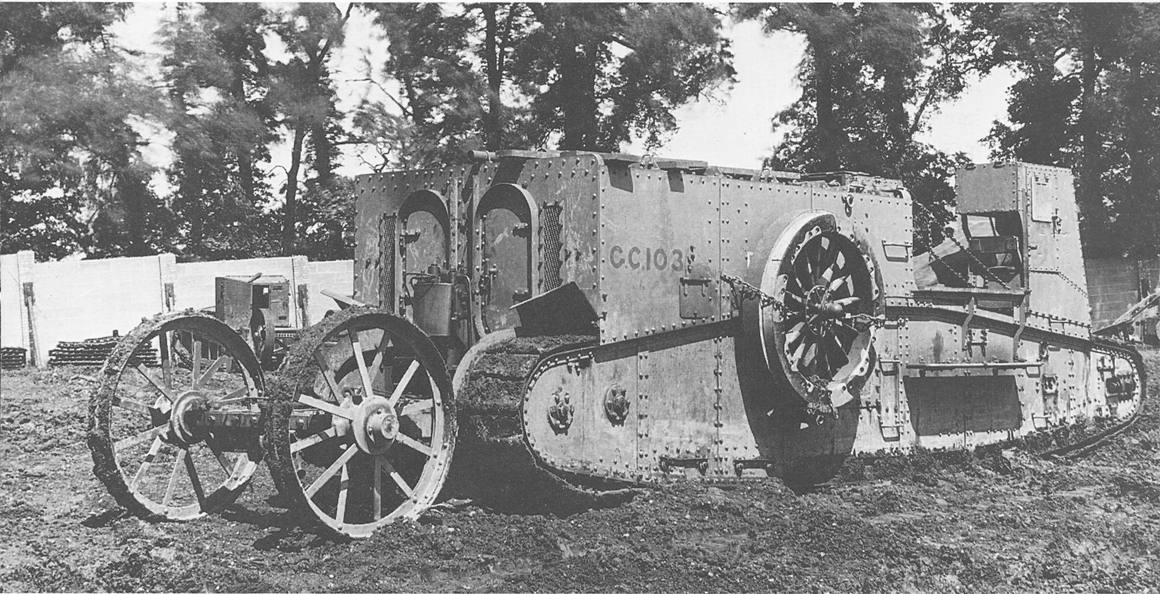

The worst possible case. A Mk I firmly stuck.

Ricardo meantime had been busy trying to improve their performance. One of the greatest handicaps was the low quality of the petrol allotted to tanks; they came last in the queue, after aircraft, staff cars and lorries. ‘US Navy Gasoline’, all that they were allowed, had what would now be called a 45 octane rating; this made it better than kerosene, but not much. Ricardo, invited to a high-level committee meeting on the subject, spoke of all this and asked whether he might have benzole. Asked why, he explained that it was not inclined to detonate, would thus allow him to raise his compression ratio and greatly improve performance. Nobody seemed quite to understand. The Chairman, Sir Robert Waley-Cohen, was Managing Director of Shell. He took Ricardo aside and asked for more information. The result was that half-a-dozen drums of petrol were sent from Shell Haven for Ricardo to test. They all seemed much of a muchness except for one that was far and away the best. Further examination showed it to contain an exceptional proportion of aromatics, which explained its good performance and high specific gravity. When Shell were asked about it they found it to come from an oilfield in Borneo; because its specific gravity was so high it met no specification and tens of thousands of tons were being burned to waste in the jungle. Waley-Cohen soon put a stop to this, but it would be a long time before the tanks got a superior brand of fuel.

Arras had, at least, been better than the Somme. Allenby issued a special Army Order praising the Tanks; Sir Aylmer Haldane, whose good opinion was worth having, even though he consistently refused to allow a rum ration and whose Corps had been the most closely connected with the operations, was ‘outspoken in his gratitude’. Only Sir Beauvoir de L’Isle (now GOC 29th Division) was against them. In his opinion – and it was an informed opinion – if infantry once became used to tanks they would refuse to fight without them. This could not be dismissed.

The bits and pieces of the First Brigade moved back to Wailly, to refit and rearm in readiness for whatever might be around the corner.

General Nivelle’s offensive, which began on the 16th, ended in utter failure. A noticeable part of the French Army mutinied or came very near to mutiny. Nothing beyond clinging to existing trenches could be expected from that quarter for a long time to come.