IT WAS TIME ONCE MORE to take stock of the position and status of the tanks. On 24 April, 1917, Stern had another of his meetings with Sir Douglas Haig and General Butler, this time in the garden of a house in the Rue Gloriette at Amiens. They talked for half an hour. Stern, fresh from Paris where he had seen Mr Lloyd George – now, of course, Prime Minister – and General Estienne at the Quai d’Orsay had a good deal to say about production problems. He found a sympathetic audience. Sir Douglas said that he would do anything to help, for he reckoned a division of tanks worth ten divisions of infantry. Stern was to hurry up and send to France all the tanks he could muster. He was ‘not to wait to perfect them but to keep sending out imperfect ones as long as they came out in large quantities especially up to the month of August.’ Tanks, after aeroplanes, said the Field-Marshal, were the most important arm in the British Army. They were ‘such a tremendous life-saver’.

Stern spoke of his difficulties with the War Office. Who, demanded Haig, was there in Whitehall who did not believe in tanks? Stern gave a straight answer: ‘The Adjutant-General’s Department.’ It was agreed that this must be stopped. Nobody tried; presumably the futility of any attempt was too well recognized.

Lack of enthusiasm was not limited to the War Office. The histories of most of the Divisions engaged in the battles of early April are pretty dismissive, and they run to a pattern. The 9th (Scottish) tells how ‘the four tanks allotted to the Division were very unlucky. Two were put out of action at the start by artillery fire. A third broke down about 200 yards from the railway on the front of 27 Brigade and the fourth failed to reach the railway after the officer in command was killed.… South of the Scarpe a Tank did good service by helping to clear the Railway Triangle which had caused a great deal of trouble to the Fifteenth Division.’ The 15th – also Scottish – make no mention of this; merely that ‘a tank, whose commander’s name does not appear in any Diary, was very skilfully and gallantly handled and was of great assistance in the capture of (Monchy).’ The 12th, whose chronicler was its own GOC, General Scott, merely observes that ‘the tanks which had been detailed to assist in the capture of (Feuchy Chapel Redoubt) were out of action, two having been set on fire by the enemy’s guns and two having stuck in the mud.’ Some histories do not mention tanks at all. No battle plan had depended upon them; they, if they turned up at all, could only be reckoned as a kind of bonus.

The best account of Bullecourt is to be found in Appendix XXIX to Major-General Sir Edward Spears’ Prelude To Victory, written in 1936. Spears, in his liaison capacity, saw as much of the wide field of operations as one man could and reports of what he did not see came in to him. His views are firm: ‘The extraordinary optimism of the tank commanders was undoubtedly an important factor in (Allenby’s) decision (to attack). They apparently believed that orders could be issued, the ground reconnoitred and the machines brought up in the short time available before daylight next day; nor did they doubt the ability of the eleven tanks to open a way for the attacking infantry.’ He speaks of ‘uncertain monsters whose commander was as inexperienced as they were themselves unreliable at this stage of the war’. Birdwood, commanding the AIF, objected to the business, says Spears, but was over-ruled by the C-in-C. There was a false start; very early on a freezing morning the Australians of 4th Division moved out into the open and lay there waiting. No tanks arrived; only an exhausted officer to say that they were still an hour behind. The infantry moved back in the dawn light like a crowd leaving a football match. When the tanks did arrive their task was hopeless. ‘While it was still dark their outline, it is said, could be seen by the sparks from the bullets that hit them. As soon as daylight revealed them stark and black against the white background every German gun concentrated upon them. They resembled moles scattered on a marble slab. … The tank crews had totalled 103 officers and men. Of these fifty-two were killed, wounded or missing. It is probable that with the possible exception of the tank that penetrated the Bullecourt defences, every one of the machines had been put out of action by 7 am.… The gross incompetence with which the tanks were handled was a serious and unjustified set-back to the new arm, for the Australians attributed their failure largely to them, a judgment true as regards this battle but misleading as a generalization.’

Spears tells of the tank crews. ‘Bravery of a very high order’, he calls it. ‘They were the targets for every hostile gun, to such an extent that their neighbourhood was an inferno from which the infantry fled; the sides of their machines were pierced by armour-piercing bullets (one had seventy such bullets in it); they knew there was every prospect of burning like torches at any moment; yet they held on their way until their iron prisons broke down or caught fire. Of the eleven machines engaged nine received direct hits and two were missing.’ It is hardly to be wondered at that ‘Uncle’ Harper and several of his peers wanted nothing more to do with tanks.

All this was mulled over again and again at Bermicourt. Bullecourt had been a disaster, but it was no fault of the Heavy Branch. Gough was widely, and on the whole justly, blamed for it. The irony of it all is that had the battle been fought a year later with a dozen Mk V tanks it would probably have been a famous victory and the General would have been lauded as the first man to understand the truth about mechanical warfare. The position was the same as if the Merrimac had been rammed and sunk by a wooden frigate and the inference drawn that ironclads were no good. It was all very well for GHQ to demand lots of tanks no matter how obsolete. This was not what the Heavy Branch had been created for. Martel’s Tank Army paper of November, 1916, and Winston Churchill’s treatise on mechanical warfare, written at almost exactly the same moment, showed what ought to be done. It was not the provision of more moles on more slabs.

All Bermicourt could do was to ram home to the authorities at home what the Fighting Side needed. So far as Stern was concerned this was pushing on an open door. No man could have applied more pressure where it was needed, but results were slow to appear. By the end of April, however, the first Mk IVs began to trickle in.

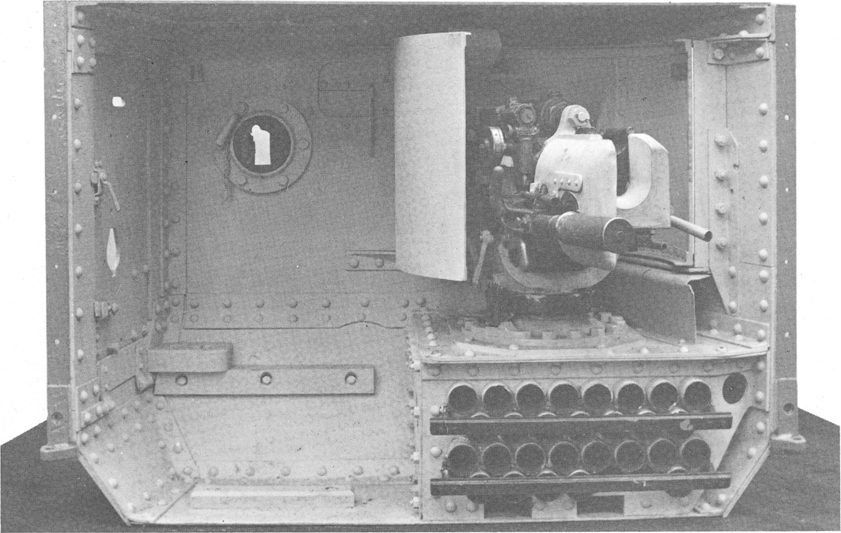

This was the tank destined to carry the burden of battle all the way through until the end of the March Retreat in 1918. In appearance it was much like its predecessors, using the same Daimler engine because nothing better was available and the same clumsy transmission. Despite all that, it was a far more serviceable piece of equipment. The sponsons were so constructed that they could be pushed inside the hull during railway journeys, and this saved much labour. Track rollers and links, the causes of so many breakdowns, had been redesigned and were much heavier and stronger than before. The dangerous inside petrol tank had been transferred to the outside and was well armoured. It was, indeed, in its armour (produced by Hadfields) that the Mk IV was so much the superior of the old machines. Its range of action on a tank of petrol was still only about fifteen miles.

The Germans, it will be remembered, had captured two tanks at Bullecourt. This could hardly have been more advantageous to the Heavy Branch had they arranged it on purpose. The German ‘K’ bullets, henceforth to be issued to every foot-soldier and machine-gunner, would go through the sides of a Mk I or a Mk II with ease. When it came to hit the Mk IV it bounced off. Not only was this helpful to the occupants but it did nothing for the morale of men who confidently expected to be able to stop the monsters in their tracks. It was disheartening to find that the trusted ‘K’ rounds were useless.

At Bermicourt a Second Brigade came into being under command of Lieut-Colonel Anthony Courage, a forty-year-old cavalryman and, like so many others associated with the early tanks, an Old Rugbeian. Courage had been in France from the beginning, had been wounded at Second Ypres and had just finished a year on the Staff at GHQ. No better choice could have been made. The men for his new command were got together in the same way as before and it might be convenient to take a look at them in their early training.

General Anley had set up the depot for the Heavy Branch at Bovington Camp, near Wool in Dorset, where it still remains. The original A, B, C and D Companies had long since gone to France and from them came the first four battalions. The name ‘Tank Corps’ was not officially granted until July, 1917, but it had for some time been used in colloquial speech and may as well be adopted now. E and F Companies remained at Wool and, with the passage of time, grew into five more battalions. It had all begun in great secrecy, arrivals and departures all being by night until the visit of a neighbouring farmer spoilt everything. He explained that for the last couple of days he had been looking after a tank; it had broken down and he had towed it into his yard with his horses. Not that he was complaining, but the Army might like it back.

This was the place to which all aspirant officers were sent and where they were put through a pretty rigorous course of training. It was not always easy to assimilate the new skills; several classes in the internal combustion engine were held close to each other in the echoing hangar and, with several instructors trotting out their ‘what we are going on with now is …’ simultaneously, it could be confusing. Especially to those who, as yet, did not know a magneto from a carburettor. All were, of course, taught to drive. The standard pleasantry when the novice, faced by a bewildering assortment of levers, lost his head and pushed or pulled everything in sight was ‘This is a tank, not a bloody signal-box’. One who was there has left an account of first impressions: ‘After a time the prospective landship commander found his sea legs and began to know his way about his strange craft, and that same evening at twilight he had his first view of tanks returning after a day’s work. It was a most impressive and fearsome sight. Over the brow of the hill, dimly outlined against the dusk, loomed a herd of strange toad-like monsters. The noise of whirring engines and the weird flap-flap-flap of the tracks, like the padding of gigantic webbed feet, filled the air. The vast snouts went up and up, and then suddenly dipped down abruptly as the creatures made for home. They made one shiver: they were so repulsive, so inhuman, so full of menace. Even though there was no danger one felt fear creeping through one’s veins. The impulse was to turn and run for dear life, but instead one stood there rooted with horror and admiration.’

Once inside it seemed another world. There was nowhere to stand up, and just room to move down the narrow gangways each side of the engine. When this had been cranked up, a job that took three or four men on the big starting handle, the din was beyond description. So was the smell. The strangest thing was to find that when everything was running nicely and the tank moving forward at a brisk pace men outside could be seen walking unhurriedly past. It was bad enough for the men in front; the gearsmen could see nothing, had no idea of what was happening or about to happen and soon learned that a careless grab for safety might be of a red-hot exhaust pipe. Like everything else in this world, people became used to it.

The pressure was merciless. The driver would be made to climb up what seemed a perpendicular cliff, stall his engine and restart by sliding backwards with the gears in reverse. They followed slalom courses marked by tapes, all turns, bends, climbs, drops and sunken road for good measure. Last came the ‘swallow dive’, a harsh test of nerve. The tank was driven up a small incline; at the top it rocked gently on the verge of a precipice. ‘Now look down,’ said the instructor. There was nothing to be seen but an apparently bottomless pit. Having digested that, the driver was told to back a little, change gear and go over the top. ‘Keep your hand on the throttle, and don’t forget directly you feel yourself falling, throttle down. Don’t open out until the tracks hit the ground.’ The instructor then climbed out.

‘Slowly the tank went forward, inch by inch it crept over the top of the incline.… Suddenly the nose of the tank tilted forward and the huge machine went down, and down, and down. He had the sensation of dropping gently through space. The throttle was almost closed, the engine ticking over: without warning the tank plunged violently downwards and, with a terrific bump the snout struck the ground. The tank, for a second, practically stood on end. One of the gearsmen in the rear, taken unawares, was hurled clean out of the sponson door. The others clung wildly to anything within reach, their feet sliding and scraping over the steel floor. Grease drums, oil cans and stray tools shot forwards in a clattering mass, landing on the driver’s back and spraying him with oil. The driver himself was at such an angle that he looked straight into the earth a couple of feet in front of his face. But the throttle was now opened out full and, as the engine raced, the caterpillar tracks gripped firmly and foot by foot the tank crawled up to the top of the crater. Then, slightly shaken but triumphant, the driver got out to watch the next tank go over.’

It was a relief to march in squads to Lulworth Cove for gunnery exercises. The targets were set up on the land side of a cliff and bombarded from across a valley. All was ingeniously worked out. The tank drove up and down with the gunner at the 6-pdr, his eye glued to its telescopic sight. Flashes, indicating battery positions, were made to come from the target area and it was the gunner’s job to hit them. Add to this much map and compass work and the making of the kind of reconnaissance report that had once been a cavalry job, instruction in that handy but sometimes dangerous to friends weapon the Webley Mk VI .455 revolver and much PT, and at the end you have a young officer trained to a degree that makes it hard to believe how the completely green crews managed the Somme battles as well as they did. Their skills may not have been great but their courage and determination shone like a beacon for the new men.

A month or so after the First Brigade had gone home, moderately well satisfied with its performance, it became clear that something was up. A detachment of tanks was set to practice climbing up what was demonstrably the model of a sea-wall. The explanation was that it represented a segment of the fortifications of Lille and few people bothered to question this. Unknown to most, a large contingent from 1st Division had been withdrawn from its positions around Nieupoort and was being introduced to the same thing. All the problems that were to bedevil the planners of D-Day presented themselves in the summer of 1917. Landing craft were built, ramps designed and the Belgian architect who had designed the sea defences between Nieupoort and Ostend was dug out and pressed into service.

The spot chosen for the attack was near Middlekerke. All the infantry battalions of 1st Division were moved back to a camp in the dunes at Le Clipon and wired firmly in, 1944 fashion. A number of pontoons 600 feet long by thirty in beam were built to Admiral Bacon’s design; the plan was that these should each be pushed by a pair of shallow-draft monitors which should also act as troop transports. The architect explained that his concrete sea-wall had a gradient of one in two with an overhang at the top. Undeterred, the planners had a concrete model made at Merlimont, near Le Touquet. A few tanks were fitted with large wooden ‘spuds’ and each was given a detachable ramp on girders, carrying a pair of wheels. The ramp was to be lowered, pushed forward until the wheels touched the concrete and then heaved up against the coping and detached. That done, the tank would climb up it and head for the open country with foot and guns following behind. When they had collected themselves they would, in conjunction with an attack across the Yser by XV Corps, take over enough country to enable them to bombard Zeebrugge and deny its use as a submarine base. It was all a deadly secret and, for a change, it remained one.

The tanks proved capable of doing what was asked of them, at any rate in the absence of opposition, 1st Division trained hard and seriously but were never called upon to show what they had learnt. The rain pelted down, as it seemed to do throughout the awful year of 1917; on 10 July the Germans mounted a spoiling attack and the advance along the Pilckem Ridge which was to have sparked the operation off became bogged down. The scheme had to be abandoned. Knowing what we cannot help knowing about Dieppe it may be that we should not regret this. It would have been a very hazardous business and, as the St George’s Day storming of Zeebrugge in 1918 was to show, the place was not all that important to the U-boat service. In addition the whole area was open to the traditional defence, inundation by breaching the dykes.

The First Tank Brigade continued at its home called Erin, just by Bermicourt, though the detached tanks did not rejoin until October. The next battle would give Second Brigade, still untried, a chance to show what it could do.

At home it was business as usual. Stern, having discovered Ricardo, wanted him to make 700 engines. General Henderson, for the RFC, demanded that this be stopped. Stern said acidly that he was bespeaking them in advance of requirements precisely in order to avoid being caught out with a shortage of engines for tanks ‘such as they were now experiencing for aircraft’. The committee sided with Henderson. Stern took no notice and doubled his order. None had yet been tested but he had great, and justified, faith in Ricardo. A month later there was another conference at the War Office at which it was agreed that the Tank Corps should be increased to nine battalions with seventy-two tanks each; another 352 for first reinforcements would bring the total up to the thousand.

He was at Bermicourt on 13 April as news of the battles became clearer. Colonel Fuller gave a lecture, emphasizing the supply difficulty for tanks in action. They had, he said, been obliged to bring up 20,000 gallons of petrol, to have four dumps and to have needed two lots of 500 men each merely for carrying parties. Next day, with Elles, Wilson and others, Stern went for a walk over the battlefields. Then he dined with Allenby who said ‘he had not believed in Tanks before but now thought it was the best method of fighting and would not like to attack without them’.

For the next ten days Stern and his party attended conference after conference. At Marly with the French technical people, at Paris with Mr Lloyd George, Lord Esher, Hankey and General Maurice, Director of Military Operations at the War Office. Finally, at Amiens, with Sir Douglas and his entourage. Stern, manfully, seems to have said no word about the misuse of the training tanks. It was all past now and there was much more to be said about the future. He left with Butler the design for a Mk VI and an opinion that ‘we could probably produce 300 a month of the Heavy Tank, and that 1,000 ought always to be kept in commission as war establishment. The Mk VI was Wilson’s own idea. Like everybody concerned in moving tanks to and from railways he hated the clumsy sponsons. His new design did away with them altogether. With an epicyclic gearbox the driver alone could control the tank and the commander was freed from the duty of working the steering brakes. In the new Mark he would be given instead the handling of a 6-pdr firing straight forward between the ‘horns’ while the rest of the crew would work in an elevated structure in the middle. The design meant much rejigging in the factories, among other things requiring that the entire engine be shifted to one side. This would have been more than a mere hiccup and no Mk VI was ever made.

——:o:——

BY OUR SPECIALCORRESPONDENT.

Mr. TEECH BOMAS.

——:o:——

In the grey and purple light of a September morn they went over. Like great prehistoric monsters they leapt and skipped with joy when the signal came. It was my great good fortune to be a passenger on one of them How can I clearly relate what happened? All is one chaotic mingling of joy and noise No fear! How could one fear anything in the belly of a perambulating peripatetic progolodymythorus. Wonderful, epic, on we went, whilst twice a minute the 17in. gun on the rool barked out us message of defiance. At last we were fairly in amongst the Huns. They were round us in millions and in millions they died. Every wag of our creatures tail threw a bomb with deadly precision, and the mad, muddled, murdurers melted. How describe the joy with which our men joined the procession until at last we had a train ten miles long. Our creature then became in festive mood and, jumping two villages, came to rest in a crump-hole. After surveying the surrounding country from there we started rounding up the prisoners. Then with a wag of our tail (which accounted for 20 Huns) and some flaps with our fins on we went. With a triumphant short we went through Bapaume pushing over the church in a playful moment and then steering a course for home, feeling that our perspiring panting proglodomyte had thoroughly enjoyed its run over the disgruntled, discomfited, disembowelled earth. And so to rest in its lair ready for the morrow and what that morrow might hold. I must get back to the battle

TEECH BOMAS.

The pace of things at home was gathering speed. Stern asked Sir Douglas to write to the War Office officially asking that the Tank become an established unit of his armies. Haig obliged and a high-level meeting took place at the War Office on 1 May. Lord Derby, Secretary of State, presided. It was a long business; the end product was a decision to set up a Tank Committee; the Chairman should be a General with recent battle experience; the Members two from the Ministry of Munitions, one from the War Office and one from the Tank Corps, this last another General. Stern saw Derby privately and protested. This was worse than ever.

The scheme, produced by two weak Ministers, could never have worked well; under another Chairman it might have limped along in some fashion but the moment Stern and Major-General John Edward Capper came face to face it died in its tracks. They detested each other on sight. Stern, not unjustly, was convinced that all wordly knowledge about Tanks (he always spelt the word with a capital T) belonged to him and his trusty band. There were, no doubt, Generals of supple mind who would have accepted this and have been prepared to take instruction from a civilian disguised as a Lieutenant-Colonel. This was not General Capper’s style, nor should he be blamed for it. His more famous brother, Thompson Capper of 7th Division, had said that in this war it was an officer’s duty to be killed; he had been, at Loos. The Cappers were of a hard race. This one’s credentials were certainly impressive. Starting his service as a Sapper officer, he had carried out public works in India, had been Commandant of the Balloon School, Commandant of the School of Military Engineering and, at 56, he had lately commanded 24th Division in the fighting around Arras. The Division had been on the left of the Canadians, in the Lens area, where no tanks had been employed. He can hardly have been unaware that, because of the failure to give them any help, tanks were not highly regarded by the Canadian Corps. It is also fair to assume that Capper had reached what Lord Montgomery would have called his ‘ceiling’. In his Diary Sir Douglas constantly complains that many of his senior formation commanders were not up to their jobs. Had Capper been fit to command a Corps, GHQ would never have allowed him to go. Stern says disdainfully that until his appointment Capper had never seen a tank. This may have been literally true, but he had certainly seen and heard reports on them. In December, 1916, the BEF Times, later re-named The Wipers Times and practically the official organ of 24 Division, had published a news item that its General could hardly have helped seeing. It appears opposite. Capper intended to introduce proper military discipline to a Department run far too long by civilians. The War Office representatives, Lieut-Colonels Keane and Mathew-Lannaw, could be counted on to back him up. Capper belonged to the ‘In And Out’. Stern preferred his Garrick Club. Their styles are not the same.

Relations with General Furse, lately Colonel Churchill’s Divisional Commander, got off to a better start when he took over from von Donop as Master-General of the Ordnance, as a very civil letter shows: ‘My dear Stern, I tried to get you on the telephone this evening to tell you how delighted I was to hear that those extra plates have been pushed off to France today for the Mk IVs. This is really a fine performance, especially in this filthy time of strikes. Bravo.’ Furse was, of course, a Gunner and the British artillery was now a huge and powerful force. Tanks were still merely ancillaries. It would not have been reasonable to expect him to devote too much time to them.

Stern addressed the meeting on the Committee’s first appearance rather as a lecturer than as what Capper would have called a subordinate temporary officer. He spoke of Haig’s talk with him – no harm in making the point that he had Sir Douglas’ ear – and gave some figures: ‘In 1916 we produced 150 Tanks; in 1917 we shall produce 1500 Tanks; in 1918 we can produce 6,000 Tanks.’ He then tore into the arrangements that brought the War Office in as a fifth wheel to his coach: ‘What possible advantage can accrue from the passage of ideas and requirements through numerous Departments of the War Office?.’ Then, fully alive to the fact that there was no chance of him being appointed dictator of all tank affairs, he made a proposal, though it must have been a painful one: ‘I wish to suggest that the rapid development can be achieved by the appointment of a Director-General of all military Tanks in England and abroad, solely responsible for everything to do with Tanks, except when detailed for action in the field. Major-General Capper has already been appointed General in Command of Tanks, but to my mind he requires these powers. His position as regards Tanks should be similar to the position which Sir Eric Geddes held in England and abroad with regard to railways.’ The reference to Geddes may have been deliberate, for on the face of it it was tactless. Geddes had gone straight from his railwayman’s business suit into the uniform of a Major-General; this was bitterly resented by the Regular Army but the army’s resentment was mild compared to that of the Navy when the same man appeared shortly afterwards camouflaged as a Vice-Admiral. Capper would not have found the comparison flattering. Anyway, the Army worked through Committees; jumped-up civilians could not be expected to know this.

Tritton’s Whippet tank was ready to go on to the production line with two 50 hp Tylor engines. Ricardo had designed an engine giving 168 hp, had the firm of Peter Brotherhood at work on the first forty of them and had arranged contracts with Crossley, Napier and Vauxhall, with Mr Windeier of Mirrless, Bickerton & Day – the leading firm in industrial diesels – coordinating arrangements. Wilson’s epicyclic gear, which did away with the need for gearsmen, was waiting to go into production. This was a masterpiece of ingenuity which enabled the torque to be shifted from one track to the other without any great effort on the part of the driver. There was no obstacle, from the manufacturers’ point of view, to the immediate production of the Mk V Tank. Had the business been left to the professionals both Mk V and Whippet might have been at Cambrai. What this could have meant we shall see presently.

It soon became obvious that under the new dispensation these things were not going to happen. Stern and d’Eyncourt drew up a long remonstrance, copies going to the Prime Minister as well as to the Minister of Munitions.

It began with a sweeping denunciation of the military authorities who had not grown up with the tank and failed to grasp the possibilities; what they could, and did, do was to disregard more and more the opinions of those who did know. First came the old sore, the machine-gun. The Hotchkiss had not been selected arbitrarily but after careful thought, once it had become clear that there would be no Madsens. On 23 November, 1916, the military authorities, against advice, had ordered that it be replaced by the Lewis. Six months later the military authorities had bowed to pressure and agreed that a change back be made. ‘The result is that this year’s Tanks will carry converted Lewis gun loopholes and Hotchkiss ammunition in racks and boxes provided for Lewis guns.’ As the Lewis gun carried its rounds in drums and the Hotchkiss in strips this was more than just inconvenience. The litany went relentlessly on. Originally it had been decided that equal numbers of males and females be made. In the winter of 1916–17 the military authorities suddenly changed this to one male to two females. Then to three males for two females. Apart from the alterations needed, there were not enough 6-pdr guns.

Then came the training tanks. Because the War Office had insisted that it must have a hundred of each in France and England they had been made and supplied, although both the Tank Committee and the Prime Minister had strongly questioned the need for so many. Sixty unarmoured tanks had been sent into battle. The excuse was that the real tanks had not arrived when they should. The War Office, ignoring arrangements made with the Tank Supply Committee, had taken away many of their skilled workmen to make aeroplanes and guns. Tank builders were still not given the same exemption from call-up as were the others. It took the personal intervention of Sir Douglas Haig, obtained by Stern at the 24 April meeting, to have this put right. There was much more of the same kind. Spare parts, training, repair facilities and many other things were dealt with, complete with evidence of how War Office meddling had made things far more difficult, and later, than would have happened under business-like arrangements. It ended with a detailed exegesis of what needed to be done: a five-man committee, all full-timers, with the Chairman having a seat on the Army Council. The distribution of duties is set out, Capper recommended by name for the top job, and no mention made of any part for the War Office in day-to-day business.

‘If these recommendations are approved, I can see every hope of carrying out the big programme which is on order this year, and the programme which has been foreshadowed for next year, but unless the new organization is formed on these lines, with the flexibility suggested, I see no possibility of carrying out either this or next years programme.’ The paper went out over Stern’s signature; d’Eyncourt added his as concurring.

The row that this stirred up made all previous ones as zephyrs to a tornado. First to march in was General Capper, fresh from Tank Corps HQ at British Columbia House in Kingsway. He had seen the CIGS, Sir William Robertson, who ordered that the paper be withdrawn. Stern, as befitted a man who had negotiated big loans to the Young Turks, was having none of that. Only when Capper gave ‘Willie’s’ personal assurance that all the things criticized would be altered did Stern agree. Two months later, nothing having been done, Stern returned to the charge.

The document was withdrawn at the end of May. The next round was fought at the end of July. In the meantime the Tanks had fought another battle, this time using Courage’s Second Brigade.

Seldom, if ever, can a battle have been prepared as thoroughly as was Messines. More guns had joined the barrage at Arras than at the Somme. Still more – 1500 field pieces and 800 medium and heavy – were available to General Plumer. No longer was there a shortage of shells; the worry now was that the guns would be worn out by such intensive use. Stores and dumps were scattered everywhere. The new port of Richborough, at the mouth of the Kentish Stour by Pegwell Bay, now came into use and large shrouded objects on flat cars embarked at the custom-built train ferry en route for Bermicourt by way of Le Havre. In the short darkness of summer nights they were unloaded at advance railheads and the new Mk IVs, the first genuine armoured fighting vehicles, clanked to their allotted places. Men spoke of them in awed whispers. The German guns were no less active and all the back areas came under steady shell fire. For eight days the artillery thundered away; from the British side 2,374 guns, on a front of 17,000 yards sent out 92,264 tons of high-explosive and shrapnel, thickened up by 70 tons of poisonous gas. This was war on the grand scale at last.

At 3.10 on the morning of 7 June, 1917, just as the darkness was beginning to thin, it happened. Nineteen great black pillars rose quietly into the sky; before anybody had time to wonder what they were came the rumble and crash of the greatest explosion since Krakatoa went up. It was the climax of the work of years. Plumer’s Tunnelling Companies – surely the least enviable job of any – had burrowed their way under the Messines-Wytschaete ridge and had now touched off nearly 500 tons of ammonal. The Spanbroekmolen crater had a diameter of 140 yards. As the earth went up the barrage came down. The tremors were felt in Kent and the thunderous crash was clearly audible in London. It was a copy of the method used by Grant at Petersburg in 1864 which had, until now, been the classic of its kind. Grant had used four tons of black powder: Plumer 470 of high explosive. The result had been much the same. ‘Set piece’ is an expression often used for battles. Only for Messines is it really apposite. General Nugent of 36 (Ulster) Division said that he had seen ‘a vision of hell’.

It was the day of the tunneller rather than of the tank, but Courage’s men were no mere spectators. The seventy-two Mk IVs were there, ready and willing, with a dozen Mk Is and IIs converted to supply machines. It was reckoned that each of these could do the work of about three infantry companies. The start was more disagreeable than usual as the Germans had soaked the rear area with lachrymatory gas and respirators had to be worn. The night being very dark, commanders and drivers had had to take theirs off with the consequence that they went forward coughing and spluttering and with tears rolling down their faces. Twelve Mk IVs went to Morland’s Xth Corps at the north end, sixteen more in the centre under IX Corps (Hamilton-Gordon); the last twenty were sent to IInd Anzac Corps (Godley) at the southernmost end, their objective being the pastoral-sounding Fanny’s Farm.

Once again, parts of the attack by tanks were excellent. On IX Corps front, a little short of the Oostaverne Line, the last objective, stood a placed called Joye Farm. The three tanks of ‘A’ battalion were not needed for the assault – possibly just as well since it took 100 minutes to cover two miles in such going – but they mopped up some machine-gun nests and put out a patrol in front whilst the infantry got themselves consolidated. As night began to come down all three were ditched. Because there was no point in trying to unditch before daylight they remained embedded. On emerging just before dawn to extricate themselves; the crew observed that the Germans were massing for a counter-attack. Being fortuitously in a ‘hull down’ position they took every advantage of it. The Lewis guns proved their un-suitability for tank work by being unable to traverse sufficiently; the crews took themselves off to convenient shell holes, the guns with them, and set to work as infantry. The 6-pdrs were better placed. As the Germans moved along the Wanbeke Valley towards them they opened up, the Lewises joined in and the attack was halted. Streams of armour-piercing bullets were directed at the hulls but none penetrated them. This went on for five hours, the 6-pdrs doing excellent service, until the message got through and the Royal Artillery took over. The counter-attack was discontinued. The tanks, however, were stuck fast. No amount of effort could dislodge them from their muddy beds and there they remained until the salvage men came for them. All went well on the Anzac front. By 7 am both infantry and tanks were lodged in Fanny’s Farm.

On X Corps front things were less successful. The History of 47th (London) Division says, laconically, that ‘A section of tanks was allotted to assist in the capture of the Damstrasse and the White Château and stables. Of the four tanks actually engaged, one was ditched 200 yards North of the Château, and two others near the stables.’ No mention is made of No 4. The Ulstermen of 36th Division were better served. ‘The 10th Inniskillings were held up by a machine-gun. A tank was just in front but the occupants apparently could not see the gun nor could the infantrymen attract their attention to it. A sergeant of the Inniskillings ran up to the tank, beat upon its side with a Mills bomb, and so gained the attention of the crew. The tank then bore down upon the machine-gun and put it out of action.’ Later comes Ulster’s verdict: ‘The tanks had been a success. They were useful in incidents such as that which has been described and they probably saved the infantry some casualties on the top of the ridge.’

More praise, though still something short of ecstatic, came from 25th Division, on the Ulstermen’s right: ‘Difficulty had been anticipated in the employment of tanks on (this) front, owing to the marshy nature of the ground on the line of the Steenbeeke. This proved well-founded, as three out of the four allotted to the Division were ditched before crossing the enemy’s front line in the initial attack. The fourth, commanded by 2nd Lieut Woodcock, got safely through. The four others detailed for the subsequent attack on the further line overcame the difficulties of the journey and were of some use to the IIth Cheshires and the 8th Border Regt, though little opposition was encountered. The Tank commanded by Lieut Tuit materially assisted the latter with its machine-gun fire in the capture of the position and some prisoners. The high percentage of casualties sustained by their personnel are a sufficient indication of the difficulties of their work.’ The last word, however, must go to that prince of ‘G’ Staff officers. General ‘Tim’ Harington: ‘Tanks were started from behind the infantry assembly trenches and followed the infantry advance; the success of the infantry, however, did not afford many opportunities for effective action by tanks before the first objective lines had been gained. Fifteen out of forty tanks were able to reach their objectives near the Damm Strass and east of Wytschaete and afforded moral as well as material support, besides drawing on themselves hostile fire which would otherwise have been directed against the infantry.’

Taken in the round it had not been a bad day; better certainly than Bullecourt. The supply arrangements had worked well, each old Mk I having five ‘fills’ aboard. A ‘fill’ was a complete set of everything a tank needed, from a full load of petrol to a complete refill of ammunition. There were no obvious lessons to be learned; nobody needed to be told that Flanders mud was a far more deadly enemy to a tank than anything the Germans might think up. They had indeed made one discovery. The ‘K’ bullet was useless against a Mk IV. The most likely antidote would be a few field guns carefully sited in the forward infantry positions. Henceforth they would always be there.