STERN’S ABRUPT DISMISSAL and the barely credible reason given for it shook some of the pioneers badly. Murray Sueter wrote that ‘It was a very real grief to me when I learnt that Colonel Stern had been suddenly hurled from the high post he had obtained.… Very often I have wondered whose path Colonel Stern was standing in.’ It was all most confusing. Mr Churchill’s letter of dismissal was dated 16 October. On 13 October Sir Douglas, importuned by that new friend of the tanks Sir Julian Byng, had agreed to a great attack by them in Cambresis; Butler, the one-time enthusiast, was still Deputy Chief of Sir Douglas Haig’s General Staff; his immediate superior, Sir Launcelot Kiggell, was not well-informed about the subject.

Mr Churchill was playing a deep game. The War Office Generals were a combination that he could not beat but there were other ways of forcing variants on the offensive. The same letter that gave Stern his congé opened up wider vistas: ‘I shall be glad to hear from you without delay whether those other aspects of activity in connection with the development of Tanks in France and America, on which Sir Arthur Duckham has spoken to you, commend themselves to you.’ The reasoning behind it is clear. America was the most mechanically-minded nation in the world and would not welcome Sommes and Passchendaeles of its own if tanks could replace masses of half-trained infantry. France had a tank programme in being, even though the French Tank Corps had little enough to show for its efforts at this date. Stern, though not even a small General, was to be Churchill’s Commissioner for Mechanical Warfare (Overseas and Allies). ‘It seems to me that your first duty will clearly be to get in touch with the American Army and discuss with General Pershing or his officers what steps we should take to assist them with the supply of Tanks.’

Stern, having delivered his usual Cassandra warning about the War Office, accepted. With his overseas banking experience on top of his tank knowledge he was the only possible man for the job.

America had, so far, proved a disappointment to Mr Churchill, who had expected the build-up in France to be far more rapid than it had been. Sir Douglas had met General Pershing at Montreuil on 20 July and had taken a liking to him, being ‘much struck with his quiet, gentlemanly bearing’. He had also made a mental note of Pershing’s ADC, Captain George S. Patton, Jr, who was ‘a firebrand and longs for the fray’. To long for the fray cannot be other than commendable in a soldier but the US Army was not yet fit to take on experienced Germans. It had no tanks; indeed it had little enough of anything. Every aeroplane and every gun used by the Americans had to be supplied by Britain or France. It was Stern’s job to see what could be done about this.

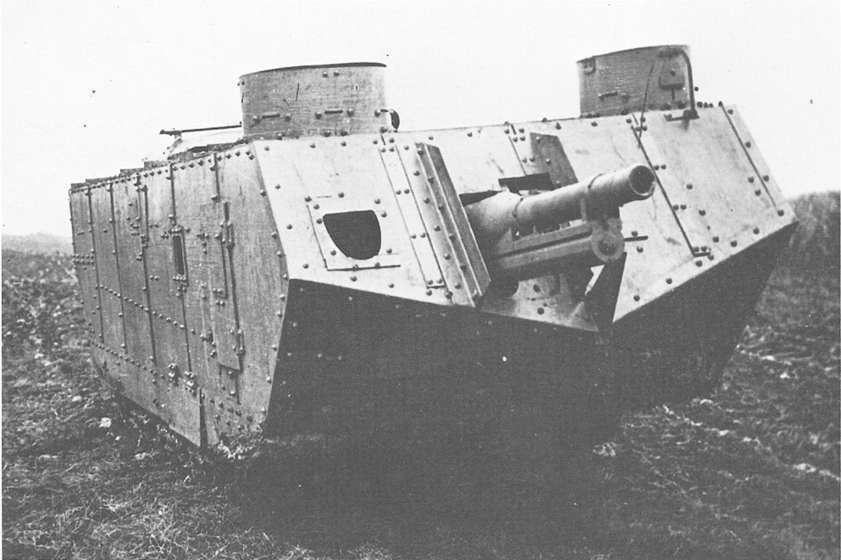

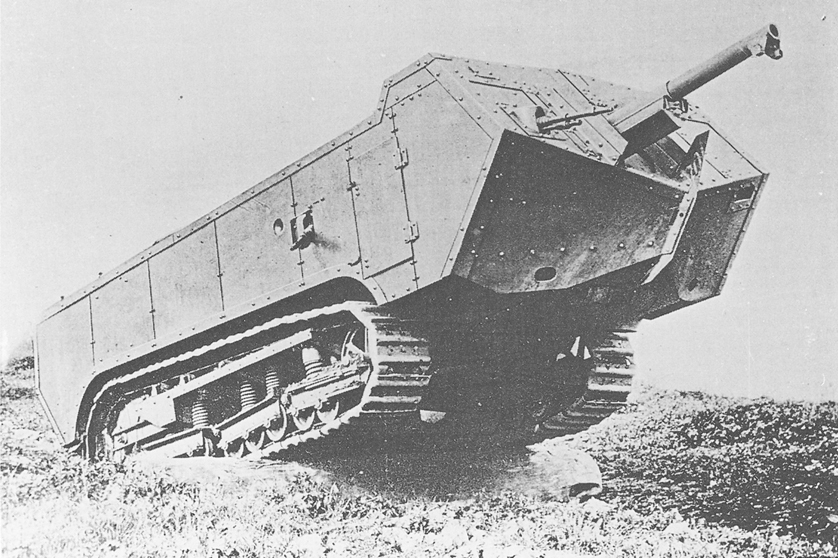

The French, thanks to General Estienne, were another matter. When, at the end of 1915, Estienne had been CRA of a Division he had, on a visit to the British sector, seen a Holt tractor at work towing a big gun. The conclusion he reached was the same as Swinton’s. In December, as ‘Little Willie’ was being discarded, he went with Joffre’s blessing to have a talk with the great Schneider engineering works. There a plan was sketched out before Estienne returned to his command at Verdun. The French War Office placed an order for 400 Schneider tanks and followed it up in April with another for 400 of the St Chamond type. Up to then British and French had kept each other firmly at arm’s length. The Schneider looked much like ‘Little Willie’ with loopholes and a lid. St Chamond was a bigger affair, resembling a ‘soixante-quinze’ on a Holt tractor, the whole wrapped about with armour plating. By April, 1917 – the Nivelle month – nine companies of Schneider and one of St Chamond were ready for business at Champlieu, on the southern end of the forest of Compiêgne. Franchet d’Esperey had pleaded – something he did not do easily – with Nivelle for their use in his attack across the Aisne around Berry-au-Bac, but had been curtly refused. Later Nivelle, much pressed, changed his mind. Eighty tanks, all Schneiders, went into action on 16 April. As the French cavalry always festooned their horses with bales of hay so did their Tank Corps hang reserve petrol cans all over the outside. They drew a fire that Spears, never a man for purple prose, calls ‘hellish’ and the cans served only to cremate the brave crews. On V Corps front, by Pontavert, another group of forty-eight made for a bridge over the German front-line trench. The Genie had not finished it. One by one the Schneiders ditched and the German guns turned on them. The reserve petrol cans caught fire and, Spears says, ‘in a few seconds they were red, glowing masses of metal, incinerators of their roasted crews. The exits were too small in most instances for them to escape.’ Thirty-two of the forty-eight were destroyed in this way. On 5 May two Schneider and one St Chamond Companies took part in a sketchily planned operation on the Sixth Army front. The St Chamonds were lucky; all but one broke down before contact was made. The Schneiders had a small success, capturing a mill. That was the sum of it all. Between May and October several more attempts were made in the general direction of the Chemin des Dames with much the same results. When the Schneiders and St Chamonds wore out, which they did quickly, they were not replaced.

A French Tank. The St Chamond.

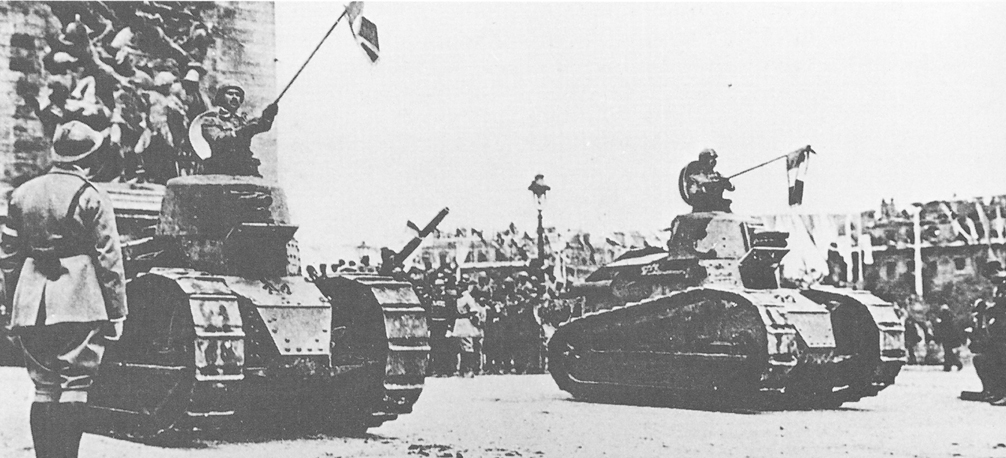

General Estienne had come to England in June, 1916, and was taken to see a Mk 1 at Birmingham. This, he reckoned, would do as an infantry tank once its initial wrongs had been put right but it was not all that he wanted. Cavalry tanks, in large numbers, were the thing. In all 3,500 of the little Renaults were ordered before the summer was out. There is a well-known French small car which is known to the ribald as ‘the Paris pissoir on wheels’.* The Renault FT 17 tankette, though painted bleu d’horizon, looked much the same on tracks. But, like all Renault products, it worked. The order went out that thirty battalions of them be formed. The amount of munitions made by France, in spite of the loss of all her coal mines and much manufacturing capacity, was amazing. Not only did Madame la Republique equip her own huge forces, she armed Greece, and contributed substantially to the arsenals of Italy and America. This additional task would be too much even for her.

Futile experiments continued with bigger and worse St Chamonds and Schneiders. A 40-ton affair was built in December, 1917; one of 70 tons was seriously projected. Stern’s task was to help co-ordinate all these wayward imaginings. It would not be easy.

Stern, rather against his wishes, was elevated to Sir Albert, KBE. This, like many people, he did not regard highly; the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire was Mr Lloyd George’s creation and was widely derided, especially by Owen Seaman with his Punch poem entitled ‘A Large Order’. Stern was no stranger to the Americans, for as long ago as June, 1917, he had arranged a demonstration at Dollis Hill for their benefit. Ambassador Walter Hines Page, Admiral Sims and Admiral Mayo had all been there and were suitably impressed. Mr Page had promised to cable President Wilson to say that ‘he considered it a crime to attack machine-guns with human flesh when you could get armoured machines, and machines, too, which he would never have believed capable of performing the feats actually carried out that day before him.’

On 11 November Stern took his letter of introduction from Mr Churchill to General Pershing. The General seemed enthusiastic and named two officers, Majors Drain and Alden, as his tank representatives. Drain was a businessman of experience who had relinquished a much higher rank in the National Guard in order to get to France with the US Ordnance Department. He and Stern took to each other at once. Within a few weeks an Anglo-Franco-American Commission had come into existence charged with the duty of producing the best possible tanks for use by all three armies in common. M Loucheur represented France. Very soon the question of engines came up. Stern had said at a tank committee meeting some time previously that although America made the best lorries in the world ‘her big engines and flying engines were not sound enough for our special purposes’. This, of the countrymen of the Wright brothers, might have sounded strange, but it was true. Plans were put in hand for a low-compression engine of 300 hp, to be called the Liberty, which could serve both for tanks and aircraft. All the the big names in the business led by Packard and General Motors, would be put to work and a super-tank would be built to house it. Major Alden would collaborate with Tritton and the others over design.

Stern set himself up in an office in Paris, for the plan envisaged a great factory somewhere in France where 1500 tanks should be built at the greatest possible speed. Loucheur could not help. France, hardly surprisingly, had neither men, machinery nor material to spare. Nor, one may fairly suspect, had she much enthusiasm for tanks. The Americans were whole-hearted in their agreement and much consultation followed upon the questions of which country should supply what.

As they deliberated, news came in of a great tank battle having been fought.

Renault FT 17s in the Victory Parade.

* Otherwise ‘Vespasienne’. The Flavian Emperor has his memorial.