IF SIR DOUGLAS HAIG had known what a junior member of his Staff had been forbidden to tell him there would probably never have been a battle at Cambrai and the tank idea might have withered away. Major (in due time General Sir James) Marshall-Cornwall was GSO2 under Brigadier-General Charteris in Intelligence. Charteris, of course, has gone down to history as the man who was constantly assuring his Chief that the German Army was about to collapse at any moment. Why Haig believed him against all evidence remains a mystery. A week or so before the assault was due to take place Marshall-Cornwall found out from prisoners – he spoke fluent German – and from captured documents that three fresh Divisions had just arrived from the Russian front to reinforce that part of the Hindenburg Line exactly where the blow was planned to fall. Charteris had stated baldly that no reserves were there. He assured his junior that all the facts he had discovered were no more than bluff. ‘If the C-in-C were to think that the Germans had reinforced this sector it might shake his confidence in our success.’ Marshall-Cornwall was so horrified that he formed up to Major-General Davidson, DMO – the same Davidson who had reproved Baker-Carr for pessimism at Ypres – and said that he could no longer serve under a man who was suppressing vital information to suit his own ideas. Davidson ordered him to stay at his post and hold his tongue.

Sir Douglas, misled into believing that the enemy was weaker than he was, agreed to the attempt at a new kind of battle: as on 15 September in the previous year, he badly needed a victory. Seldom had so much concentrated thought gone into preparation. Byng, successor to Allenby at Third Army, had a visit from Elles at Albert in September. Both were thinking on the same lines, of a swift armoured raid designed not so much to occupy territory but to kill and chivvy – Williams-Ellis’s word – Germans. Fuller had been at work on it for some time.

Whatever other people might think, the German High Command had not been captivated by the tank. Probably, even more than the War Office, Hindenburg thought it unsoldierly. He had led his company up the slope at St Privat in 1870 against the massed Chassepots and that was the proper way to conduct a war. At about the time of Third Ypres General von Freytag-Loringhoven was writing disdainfully about the subject: ‘The English and the French sought to prepare the way for their attacking troops by the employment of battle-motors – the so-called tanks.’ In his book Deductions From The World War the Baron makes no other mention of them. Gas, of course, was quite another matter. All the same somebody had measured the captured ones, found out that their trench-crossing maximum was ten feet and had widened the Hindenburg Line throughout its length to twelve. The last letter Stern had had from Elles before his dismissal had said, ‘We are very anxiously depending on you to solve two main conundrums that confront us. (a) A device to get the Mk IV and Mk V Tanks over a wide trench and (b) some very simple dodge by which we may be able to put on the unditching gear from the inside of the Tank.’ Stern’s people were working on these things; Squadron 20 usually had ideas. So did Colonel Searle at the Central Workshops.

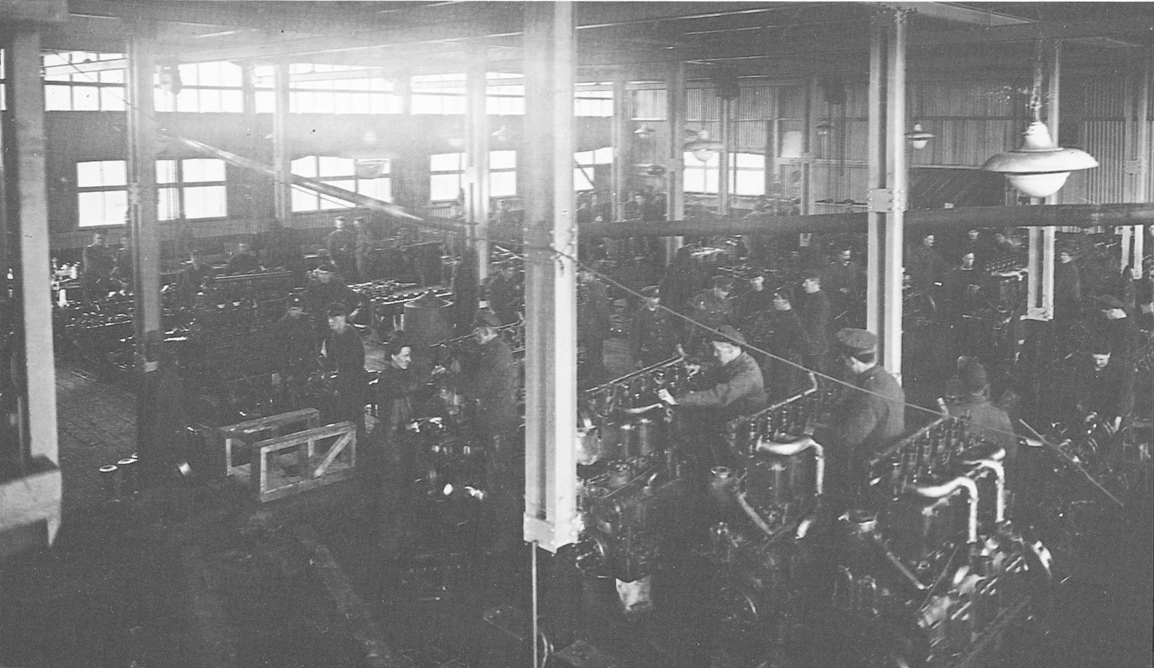

As with the tank itself, mediaeval history came to the rescue. For many centuries besiegers everywhere had had to think out the best way of crossing unbridged ditches. The school solution had been worked out long ago and had probably been as familiar to Archimedes as it had been to Wellington’s Colonel Fletcher. The only difference was in size. Fascines – the very word recalls the lictor’s bundle of rods – would probably serve nicely, provided they could be made big enough. The British-occupied area of France abounded with saw-mills, mostly worked by steam traction-engines, which were reducing woods and forests to gun platforms and trench revetments. Colonel Searle set his Labour Corps to work. There was a particularly large saw-mill by the side of the St Pol road, very near to Bermicourt, and arrangements were made for great quantities of brushwood to be made available. Squadron 20, always willing helpers to their own landships, were sent in search of chain, from the Navy or from anywhere else that it might be found. In all 21,000 bundles of brushwood were put together. That done, eighteen tanks were used for making bigger bundles out of the bundles, some sixty or seventy to each fascine; the chain fastenings were pulled tight by the simple expedient of making each end fast to one of two tanks which then drove slowly off in opposite directions. The finished article weighed a ton and a half. So great was the pressure that, months later, an unsuspecting infantryman in search of firewood was killed by the sudden springing open of one of them after he had filed through the chain. 350 of these aids, along with no sledges were turned out by Central Workships in time for the battle. Though it took twenty strong men to roll a fascine through the mud, these were at last available. In August, 1916, the British Military Attaché at Peking, Lieut-Colonel David Robertson, had suggested that some arrangement might be made with the Chinese Government for the employment of civilian labourers to work in France, mainly on the very important business of road-making. The War Office, liking the idea, sent an official representative to the Chinese capital; the result was that, with powerful help from the authorities in Hong Kong and Weihaiwei – then a British Protectorate – together with that of the local missionaries large numbers of men were engaged and shipped off. By the end of the war, which China joined in August, 1917, 96,000 Chinese were in France. They soon won high praise for their work and good conduct. One of the largest camps was at Houdain, no great distance from Bermicourt, and Colonel Searle gladly employed as many as he needed. It became apparent that many of the labourers were fit for better things than pushing and shoving; a good number – exact figures are elusive – came to work in the Central Workships as fitters and proved themselves excellent at the job.

Fuller, Martel and Hotblack worked out a simple drill based, according to Fuller, on one used by the Persians of antiquity. Once a fascine had been dropped it was gone for good and there were three trench lines to be crossed. The tanks were likewise mustered in groups of three – always a number of mystic significance to Fuller – each bearing a fascine on its roof. On hard chalkland there was no need for unditching beams. The job of No 1 was to trample through the wire as far as the parapet of the front line trench; this was not to be crossed. The tank would then execute a left wheel, move along a prescribed length and shoot up everything it saw. Thus protected, Nos 2 and 3 would move up, each aiming for the same spot. No 2, the left-hand tank, would drop its fascine in the trench, drive over it and then would itself swing left and use its guns to thicken up the fire of No 1. No 3 would also cross on the same fascine and head straight on. When it came up to the second trench it would drop its fascine, cross on it and treat the second trench as No 1 and 2 were treating the first. As soon as No 1 saw that No 2 was over and shooting it would come back, cross both trenches and head for the third line into which its fascine would go. Then it would resume the business of shooting anything in the trench that moved. The infantry were similarly told off in three groups; Trench Clearers, who would go in immediately behind the tanks, Trench Stops to net the rabbits and Trench Garrisons to take over captured positions. It was simple and sensible, though there was little enough time for rehearsals.

The artillery would stay silent, not even being allowed to register from its new positions. As the tanks arrived on their first objective down would come the barrage, much thickened up by smoke. Since GHQ had insisted that this must be more than a raid and the usual cavalry breakthrough was anticipated with the customary confidence a proportion of the tanks was kitted out with grapnels; these were to be trailed behind, pulling away the wire like balls of knitting wool and making nice wide pathways fit for horses. The original plan had, by early November, snowballed into a combined affair to be undertaken, at the start, by five full Divisions.

One of the Divisions to take part in the initial assault was ‘Uncle’ Harper’s 51st Highlanders. At the pre-battle conferences Fuller’s plan, which had already been approved by General Byng, was carefully explained. The infantry was to follow the tanks in single file, keeping as close as it could for protection. ‘Uncle’ Harper was at least honest. While every other Divisional General nodded and agreed to give the plan a try, ‘Uncle’ flatly refused. He knew all about tanks. They broke down. Always had done. He was not going to see his ‘little fellers’ stuck out in the open under fire from everything behind a lot of useless lumps of metal. He would cross his start line an hour after everybody else. When the conference ended he buttonholed Baker-Carr and denounced it as ‘a fantastic and most unmilitary scheme’.

‘Uncle’ had the measure of his Corps Commander. Sir Charles Woollcombe was in his 62nd year and, although he had been commissioned as long ago as 1876 he had not seen a great deal of active service. Although he had a reputation for keeping good discipline, Woollcombe had only been in France for a short time. Whether Harper protested at the Conference or whether he kept quiet, privately resolving to do things his own way, is uncertain. Probably the latter. An experienced General, such as Maxse or Haldane, would have wrung from him an acknowledgment that he knew what he had to do and would comply. Woollcombe seems to have let him get away with it. The relatives of some tank crews might justifiably have said that he got away with murder. The Division neighbouring the 51st, the 62nd, good West Riding Territorials, were under Major-General Braithwaite; in 1907 he and ‘Uncle’ had been Instructors together at the Staff College. Eight years later, as CGS to Sir Ian Hamilton, he had come near to following his Chief into oblivion. Hamilton had written of him that ‘by the Lord they shan’t have the man who stood by me like a rock during those first ghastly ten days’. Braithwaite survived, and for his penance was given command of this second-line Division from which nobody expected spectacular performance. He made it into one of the best in the BEF, before he was, deservedly, promoted to command a Corps.

Cambrai developed from the designed land-borne commando raid into another ten-day slogging battle. There is no shortage of accounts of it but here it is only possible to tell of the work of the tanks. Three hundred and seventy-eight fighting machines were allotted to Divisions, roughly the tank strength of 1 ½ armoured divisions of 1944. In all, the Tank Corps fielded about 690 officers and 3,500 other ranks. The disparity between numbers of men and numbers of vehicles demonstrates how complex were the arrangements before and behind. Hugh Elles, as everybody knows, issued his Special Order No 6. In soldierly language he reminded his crews that everything depended upon their judgment and pluck. This was not hyperbole. Had either failed there would have been no Tank Corps by Christmas.

General Elles led the attack, as an Admiral of landships should, standing in a tank called ‘Hilda’ wearing his red hat and carrying on the end of his ashplant a flag of his own devising. He and Hardress-Lloyd had had it run up from materials they had bought at a little shop in Cassel. The choice of colour proclaimed a primitive heraldry. Mud, blood and grass green for the fields beyond. There could be no harm in a little panache to colour a war lacking in such things.

When Baker-Carr had protested that if his commander could ride into battle like Chandos or du Guesclin he could do the same, Elles threatened him with ‘terrible things’. A commander’s place, he said, was at his own HQ. For his part he compromised, riding defiantly on Hilda’s bridge, following tapes painstakingly laid out by Hotblack and the others until she had crossed her first objective. Then, much to the crew’s relief, he dismounted and walked home, impatiently pushing aside groups of German soldiers anxious to surrender themselves to him. The going, across chalk downland uncrumped by shells, was excellent. The Tank Corps, well prepared for what it had to do, was in high spirits. This, at long last, was the opportunity to show what it could achieve.

Spot on 6 am on that memorable 20 November the whisper went round, ‘Here they come’. As groups of tanks moved forward, led in the early stages by their subaltern commanders on foot through a dawn mist, a thousand silent guns bellowed out as one. Down came the barrage with a roar that made the earth quake underfoot as the infantry, all save Harper’s ‘little fellers’, rose up and followed the Mk IVs. To begin with it resembled a ceremonial parade, all hands keeping their exact distances. Each section of tanks moved off in arrowhead formation, a hundred yard perpendicular between apex and base, itself a hundred yards across. At the same distance behind the two rear machines followed a platoon of infantry in extended file. This was the kind of thing Mr Churchill and Colonel Swinton had long envisaged and it worked.

Belts of barbed wire, skilfully erected at leisure by Germany’s abundant slave labour, of a depth and thickness that no British soldier had seen before and much of it on reverse slopes that no gun could reach, were trampled down as gumboots trample nettles; here and there they were forcibly pulled out and cast aside by the grapnels. The battle drills so carefully worked out by Fuller and the others did everything that was expected of them. Trenches reckoned to be takeable only at the price of great losses fell for half-a-dozen casualties. The cavalry performed its now customary function of cluttering up all the roads in rear that were urgently needed for the passage of supplies and ammunition. One Canadian squadron did some useful work during which most of its horses were killed, but, apart from that, it was an idle day for horsemen. Why they were there at all has never been satisfactorily explained. Baker-Carr’s 1st Brigade had obeyed orders and cleared a way for the 2nd Cavalry Division of Major-General Mullens (‘Gobby-Chops’ to his many unfriends). All he saw of them was a single liaison officer who repeatedly took back messages that all was clear; by the end of the day he was almost in tears.

Only at the crucially important village of Flesquières, Harper’s first objective, did the plan fail and that because no attempt was made to carry it out. Sixteen tanks duly arrived on the ridge. Ahead of them lay Graincourt and beyond that the ultimate objective, Bourlon Wood. The Highlanders, who should have been on the ridge within a couple of minutes, were not to be seen. The tank crews, having nothing else to do, wandered around in awe looking at the great works they had captured by their own efforts. Then the German artillerymen recovered themselves and began to fire from a nearby orchard over open sights. With no infantry to help them the Mk IVs dodged the shells as best they could, but with the complicated business of drivers signalling to gearsmen and waiting for them to do their parts this was pretty ineffective. One by one they were picked off and smashed. When the 51st finally arrived they had a far harder time of it than would have happened if their GOC had obeyed orders. There was no longer any question of storming Bourlon Wood. The adjacent 62nd Division had done wonders in taking all its objectives and had outflanked Flesquières. When General Braithwaite offered to enfilade the place Harper refused his help.

Only on the right was success less than complete. The bridge across the Scheldt Canal at Maisnières had been partially destroyed by German sappers and, as everybody concerned knew, this was the key to the very important Rumilly-Seranvillers ridge. The commander of the leading tank, under no illusions about his chances, went for it bald-headed. The gamble nearly succeeded, but not quite. The tank reached the half-way mark but then the last steel girders buckled and snapped, gently lowering the machine into the water. As other tanks arrived they did what they could by providing covering fire, but it was too late. The Germans had time enough in which to fall back on the half-complete Maisnières-Beaurevoir Line. ‘Bald-headed’ suggests the Marquis of Granby but it is not inapt here. The Tank commander lost his wig in the canal.

By tea-time on the 20th the battle was over for most of the Tank Corps. Losses had been heavy, mostly from field guns used in an anti-tank role. The advance, however, had been something without parallel in this war, about eight miles on a front of 13,000 yards; 8,000 prisoners and more than 100 guns had been taken. The supply tanks had done what they were needed to do; wireless tanks had passed messages swifter than the best of pigeons. The sum total of casualties did not exceed 1500. In England church bells rang, though the ringers were soon to regret it. Colonel Swinton, far away from the battlefield, received a telegram. ‘All ranks thank you. Your show. Elles’.

The next couple of days saw the end of the Armoured Division style of battle and a reversion to the penny packet. Composite companies were quickly put together but there could be no repetition of Day 1. The infantry were physically exhausted and the new formations unpractised at working with armour. ‘Consequently,’ says Williams-Ellis, ‘many strong points, though they were finally captured, gave us more trouble than they should.’ Thirteen tanks of B Battalion smashed their way into Cantaing and two more drove the Germans from Noyelles, no losses being suffered in either operation. Twelve more, from H Battalion, were ordered to make the long slog of six miles across the open to see what they could do about Fontaine Notre Dame, the furthest point reached by anybody. They got there at 4.30 pm, had a battle lasting an hour and handed the village over to the infantry, who were themselves driven out next day. On the 23rd the tanks came back, twenty-four of them. A full day had sufficed to make the place inexpugnable; every building was a fortlet and in the narrow streets it was impossible to bring the guns to bear. The clumsy Lewis had a very small traverse; it might have been another story given either Madsen or Hotchkiss. As it was, the crews were lucky that November days are short and that darkness gave them a chance to withdraw.

On the same day thirty-four tanks of 1st Brigade supported 40th Division in their brave attack on Bourlon Wood and village. They drove through the wood but once again the village was prepared to receive them and the infantry were worn out. Fontaine and Bourlon remained in German hands.

Hankey wrote in his diary for the 21st: ‘The great event today is the full news of the great tank attack near Cambrai, where 400 tanks have burst right through all the German lines of defence and let through the cavalry. It is in a sense a great personal triumph for me, as I have always since the first day of the tanks advocated an attack on these lines.’ Then came the counter-attack, bolstered up by the divisions from Russia whose presence had been kept from Haig by his own Chief of Intelligence. By the end of the month losses and gains of all kinds about balanced out.

Vickers Medium Mk 2. For years the backbone of the RTC.

The Tank Corps had an unexpected epilogue. Colonel Courage’s 2nd Brigade, on the right-hand end of the front, had been reduced to about thirty effectives and had been doing fine work in helping to hold up the German onrush. Baker-Carr, his end being fairly quiet, paid a visit to Third Army HQ where he met Major-General Vaughan. The withdrawal was a disappointment, Vaughan said, but he hoped that all the tanks would get out all right. Baker-Carr, knowing nothing of this, pressed for information. Apparently orders had been sent to Elles that the line was being pulled back to the original one and that all tanks had to be behind it by II o’clock. By inspired staff work the message had been addressed to Elles by name and sent to the low-grade cabaret in Albert which was serving as Tank Corps HQ. Elles was at GHQ; the order lay unopened on his table. With so many hours lost and with tanks littered about the old battlefield either under or awaiting repair there was no possibility of compliance. A number of tanks had to be left stranded in territory that would soon be occupied by the Germans. Frantic efforts were made to blow them up but some were bound to be in a state capable of being put back into service. As they were – by the Germans.

General Woollcombe was removed from his command. The discerning reader will have guessed the name of the man whose superior philosophy demanded his advancement. ‘Uncle’ Harper got his Corps. 179 tanks were out of action, though only sixty-five of them by German fire, before Bourlon Wood was reached.

At GHQ there were also changes. The ebullient Charteris and the lugubrious Kiggell – so unsuitably called Sir Launcelot – both had to go. Kiggell, best remembered for his ‘Good God, did we really send men to fight in that?’, left as his opinion that Cambrai had been all very well but such an operation could never be repeated. Sir Herbert Lawrence who replaced him was a man of other mettle. Butler also was removed by popular demand. Sir Douglas, who had a high opinion of his capability, tried to have him promoted to Kiggell’s old position but anti-Butler feeling was too strong. He was given instead the chance to show what he could do as a commander. General Pulteney, creator of IIIrd Corps, had not come too well out of the new style of warfare and was replaced by the former Deputy Chief of the General Staff.

Bertie Stern, never the most patient of men, was left to meditate what might have happened had a few companies of Whippets replaced many regiments of horses. Had he only been given his head, with the powers promised him by Sir Douglas so long ago, it could have been arranged.