UPON THESE THINGS Stern pondered at Rue Edouard Sept, numero deux, in Paris, the office he had procured for the Anglo-American Commission. Before setting himself up there Stern had had a meeting with Mr Churchill; it took place in London on 26 November, a day that saw the last few surviving tanks of F and I battalions still working away at saving the lives of men of the Guards Division and Braithwaite’s 62nd. It was also the eve of the great German counter-thrust. Stern, forgivably, gave a reminder that it was only a month since he had been convicted of piling up useless machines.

Mr Churchill was a very worried Minister, and that with good reason. U-boat sinkings had drastically reduced the flow of iron ore from the Spanish Biscayan ports; Passchendaele and its associates had drastically reduced the number of effective fighting men in France. The Americans had not yet arrived in significant force, whereas the German army in the west was gaining strength every day. The French army was on the ropes, though by no means out of the fight. His own vision of the mechanized battle had never wavered and he made some calculations of his own. Infantry strength was greatly reduced, though artillery remained tremendously strong. He put each arm about 40% of the total. The RFC he reckoned at 10%; the cavalry, although two Indian Divisions had gone east, still made up 3½%; another 4% went to the Machine Gun Corps and ½% to the Gas experts. The 2% remaining was the Tank Corps. A long and carefully thought-out plan went to the Cabinet proposing a cutting-down of foot and guns, the reduction of horse to ½% and the increase being in aircraft, machine-guns, gas and the tanks. These last would be multiplied four-fold. The date of the paper was 5 March, 1918. The events of 21 March overtook it.

Early in December, less than a week from the anti-climactic end of Cambrai, Mr Churchill had, however, done something to ensure victory in 1919 despite all the gloom. The Anglo-American Commission was set up, with Stern and Drain as Commissioners, charged with building great numbers of a tank superior even to the Mk V which would be made with British hulls and the Liberty engine. The Commissioners would build a factory in France capable of producing 300 tanks a month to begin with and rising to 1200. In 1918 there would be 1500, with a distribution of bits and pieces carefully set out. All this was incorporated in a formal Treaty, signed on 22 January, 1918, by Ambassador Page and Arthur Balfour. France made available a site at Neuvy-Pailloux, a couple of hundred miles south of Paris and within easy reach of the American-used ports of St Nazaire and Bordeaux. Annamite labour in sufficient quantity would also be found by France.

All this lay in the future and there were pressing problems nearer home. Tank production, largely because of steel shortage, had fallen below the 200 a month that had been achieved during 1917. Stern continued to badger, blaming all this, perhaps not entirely fairly, on the War Office. As he had the ear of Mr Lloyd George far more frequently than did General Capper, he managed to get the matter raised in Cabinet with useful results. There was much gloom in London in early December, 1917. GHQ was distrusted as incompetent and Mr Lloyd George would gladly have sacked Haig had he only dared. GHQ, with Mr Churchill as ally, complained that something like a quarter of a million troops who ought to have been in France were kept at home for specious reasons connected with invasion threats. Manpower was running very low. When the Navy demanded 90,000 more hands the Admiralty received its first rebuff for years. Sir Douglas was ordered to take over more of the French line, taking his right down to Barisis on the Oise. It was in a shocking state of disrepair and demanded much labour to make it anything like defensible. He was told, though not in so many words, that the men who should be working on it were rotting in their muddy graves by Ypres.

The immediate business of tank people was to get rid of the Mk IVs and bring in Mk Vs and Medium ‘A’s, alias Whippets. A trickle had begun in the autumn but it was woefully insufficient. The Cabinet’s new Tank Board looked promising. General Seeley was President with Mr Maclean (the civilian successor to Admiral Moore) as his Deputy. ‘Boney’ Fuller was a member, along with General Furse, d’Eyncourt and Stern. Elles was added later, along with that founder member, Ernest Swinton. With men of this quality at work it is not remarkable that things got on the move again. Their programme of 5,000 modern machines during 1918 began to look possible.

In France the building of the Neuvy-Pailloux factory was handed over to the English firm of Holland & Hannen, with its supervision entrusted to Sir John Hunter of the Ministry of Munitions. Stern was not among his admirers, and it seems to have been mutual: ‘All through the early months of the year Sir John Hunter objected to any advice or help on our part,’ ran one of his letters to Mr Churchill. Furious telegrams complaining of delay and mismanagement flooded into Whitehall over the signatures ‘Stern and Drain’, It sounded much like ‘Sturm und Drang’.

Relations with General Capper had not improved. A report on the tank operations at Cambrai was drawn up fairly quickly and submitted to the Ministry of Munitions. Stern asked for a copy and was brusquely told that he could not have one. As usual he went back to Mr Lloyd George – something that the General would have furiously resented – and Capper was ordered to hand it over. Cambrai had been fought during a fortunate interval in time. The Mk IV, because of its clumsy ancillary gearboxes – which often stuck in moments of stress – was a sitting duck to any sort of field gun, as the Germans were beginning to realize. Tests carried out in France for Stern’s committee by an engineer named George Watson suggested that it might be even worse than was generally thought. His report, dated 26 September, said that he was convinced of the Mk IVs inability to be driven up a gradient of more than 35° from horizontal and in 2 to 3 feet of soft ground he was doubtful whether it would climb anything at all. In several parts of the Hindenburg Line, he pointed out, the relation of width, depth and height of parados was such that the angle might be as steep as 50°. The drivers and reconnaissance officers at Cambrai must have been uncommonly skilful, uncommonly lucky or a bit of both. In any case the Mk IV must not be used again in an important attack.

On 8 January, 1918, Stern sent the Prime Minister a detailed appreciation of the war situation. Lay it alongside Mr Churchill’s Munitions Estimates for 1918 of a couple of months later and it would be hard to tell who had written which. Free from War Office interference their minds had met completely. But the War Office still had shots in its locker.

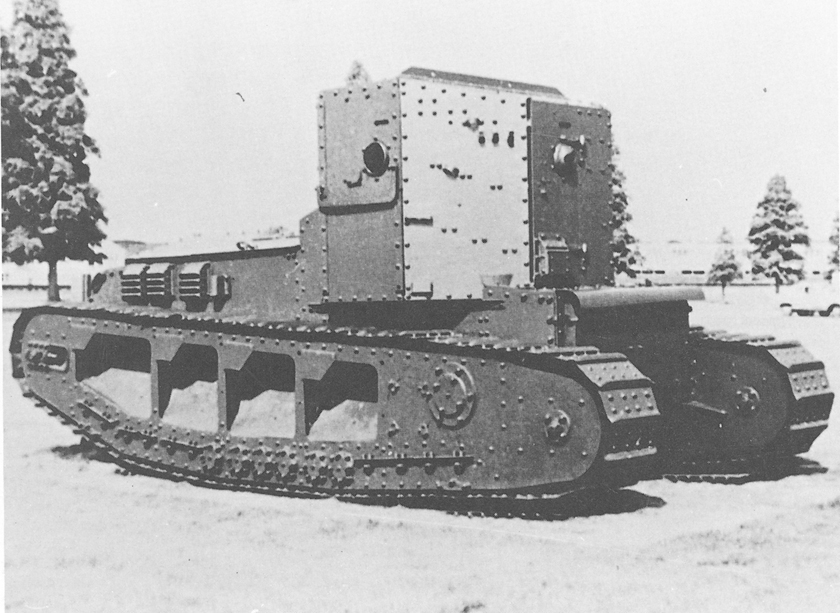

Between Cambrai and the March Retreat the Tank Corps had time for rest and retraining. All the battalions were withdrawn to the sea coast around Le Treport. Everybody knew that they were in the eye of the hurricane and that they must prepare themselves for battle of a kind not previously experienced. The tank in defence was a new concept. The battered Cambrai veterans, about a third of those which had gone over, were thoroughly refurbished and with new arrivals from home the total of Mk IVs came up to 320. From Squadron 20 at Le Havre came also the first fifty Medium As. The Whippet, as everybody called it, was Tritton’s Chaser brought up to date. Twenty feet long, nearly nine wide and turning the scales at fourteen tons, it looked much more like the tanks of today. Each track had its own engine and it was steered by varying the speeds. A cab was perched on top of the tail end, with three Hotchkiss guns inside, and it could manage a top speed of 8 mph. Much was expected of the Whippets, but they were the new cavalry and cavalry was not designed to hold positions. It did, however, show to frustrated men that better tanks were on the way.

It was impossible to put any sort of date on when they might arrive. Stern continued to pester Mr Churchill; when rumours reached him of the tanks being built by Germany he pestered the War Office also. Finally he pestered the Prime Minister, to whom he had already sent a long paper setting out his own Variants On The Offensive; having had more experience than other men, he wrote the most practical exegesis of the whole business. His reward, if such it can be called, was that a Cabinet on 8 March decided to adopt an immediate programme of building 5,000 tanks. Mr Churchill, not a member though lunching at least once a week with Mr Lloyd George and F. E. Smith, was told to see to it.

It was on 8 April that Lord Milner, now Secretary for War, visited Stern in Paris and much had happened between these two dates. Stern returned to the charge. There ought to be a central authority to develop Mechanical Warfare ‘untrammelled by all the vested interests of all the established branches of the War Office. In this way, a highly technical development could be carried out by a practical man with the advice of the military authorities.’ Modesty forbad him to name the most practical man, but he made it very clear to Milner that, had he been given his head, the original figure of 5,000 tanks for 1918 would never have been cut to 1350 and the Army would now have had far more in service than it did. Stern begged Milner to talk to d’Eyncourt. Apparently he did, for ‘from this data a new era of progress started for Mechanical Warfare at the War Office’. It was only just in time. The war might easily have ended with a German victory soon after 21 March.

Dawn on 21 March, 1918, saw by far the greatest attack in the old style. The Kaiser’s armies had at last been able to mass an enormous superiority in guns and men with which they were determined to fight and win the last and decisive battles. They came very near to doing it. Six thousand guns lashed a forty-mile front with gas and high explosive under whose cover three-quarters of a million trained men advanced to the assault. Most of this fell upon General Gough’s makeshift defences and, despite much unrecorded heroism by men who died where they stood, the surge came dangerously close to Amiens.

This was not the kind of battle upon which 370 tanks, most of them worn out, could have much effect. Most of the Mk IVs fought their last fight until they had to be abandoned for want of petrol or were picked off by German field guns. Many crews removed their Lewis guns and joined with the nearest infantry as a welcome reinforcement. Only about 180 ever got into action and even Clough Williams-Ellis could not find out enough to tell a coherent story of the doings of all of them. The Whippets, apart from one piece of misfortune, did far better. They had recently been issued to the 3rd battalion at Bray-sur-Somme, a camp that was destroyed early on in the fighting. Several Whippets were temporarily out of action with engine troubles of a minor kind; as spares could not be got forward in time they had to be blown up. Those that remained proved excellent value and far more reliable than anything used before.

According to his own account, ‘Boney’ Fuller sat upon the top of Mont St Quentin, just outside Peronne, and watched the Army fall back. There he put to himself the question ‘Why are our troops retreating?’ and answered it with ‘Because our command was paralysed’. Fuller’s thoughts were always in a rarified atmosphere. The simple explanation that Gough’s army was in the position of a bather on the shore engulfed by a wave of gigantic size, was too simple by half for him. His physical resemblance to the Corsican was misleading, for this ‘Boney’ never subscribed to the belief that ‘In war, moral considerations make up three-quarters of the game; the relative balance of man-power accounts only for the remaining quarter’. Fuller had never, apart from some scrimmages in South Africa, commanded even the smallest number of men in battle. His article of faith was the antithesis of this one: material, not morale, wins wars. He had been told about a light tank, not yet in existence, which could manage 20 mph and with this he reckoned the tide could be turned; not perhaps in 1918, which must look after itself, but in 1919 or possibly even 1920. It was against this discouraging backcloth that he mused upon his Plan 1919. Much the same idea seems to have occurred to Sir Henry Wilson a few days earlier. March, 1918, however, gave little scope for ‘psyching out’ the German army.

On 26 March two companies of Whippets did sterling work; once again it was ‘Uncle’ Harper who made it necessary. The blow had fallen on a Thursday. On the following Monday, in Gough’s words, ‘The Third Army gave up Bapaume and fell back behind the Ancre and north of it, a distance in places of over 10 miles. A very dangerous situation developed on its front during this afternoon. Its IV Corps (General Harper), although it consisted of six Divisions, left a gap of four miles in its line, from Hamel to the north of Puisieux, which was some twelve miles north of the left flank of the Fifth Army. Into this gap the Germans had penetrated to a depth of three miles, and had seized Colincamps before nightfall. Colincamps is barely nineteen miles north-east of Amiens.’

Two companies of the 3rd Tank Corps arrived at Mailly-Maillet about noon on the 26th. The village stands about a couple of miles due south of Colincamps. Nobody had the slightest idea of what was going on, bar the fact that infantry were still retreating and the Germans could not be far away. Three hundred of them soon arrived, in close formation, and were met head on by the leading Whippets as they rounded the corner of a wood. The Hotchkisses opened up briskly; the Germans, those who survived, either fled or surrendered to the infantry who were following behind.

A Whippet at Mailly-Maillet during the March Retreat with men of the New Zealand Division.

As the retreat went on a job of sorts was found for those tanks that were still in business. Very often it was impossible to tell who, for the moment, owned any given village. It cost far less in lives to send a tank to find out than to put in a platoon of foot-soldiers. Several times the tanks found villages hostile and fought it out for an hour or two. With guns red-hot and petrol almost exhausted they then tried to make their way home. More often than not they had to be abandoned for lack of fuel and efforts were made to blow them up.

Much the same thing happened during the German offensive on the Lys. These were not tank battles, at any rate not with the few veterans that were still operational. It was at Villers-Bretonneux on 24 April that a milestone in history was passed. A section of three tanks, a male and two females lay up overnight in a gas-drenched wood behind the little town among the swollen bodies of dead horses and ‘birds with bulging eyes and stiffened claws’. At dawn on the 24th two German aircraft spotted them and dropped flares. A deluge of shells, many of them being asphyxiating gas, crashed down into the wood. The crews, choking into their respirators, climbed back into the machines and moved a little to the rear. Wounded men and stragglers drifted back; Mitchell, the subaltern in command of the male, agreed with a nearby battery commander that when the Germans arrived his tanks would take them on over open sights. Several members of his crews had to be taken out, overcome by gas and hors de combat. Eventually an order arrived: ‘Proceed to Cachy switch-line and hold it at all costs.’ The three Mk IVs crawled off, passing right through the German barrage at the best speed they could manage. All of a sudden an infantryman appeared, waving his rifle and yelling ‘Look out, Jerry tanks about’. Captain Brown disembarked hurriedly and ran across the shell-swept field to warn his females. Lieutenant Mitchell opened a loophole and looked out. ‘There, some three hundred yards away, a round, squat-looking monster was advancing; behind it came waves of infantry, and farther away to the left and right crawled two more of these armed tortoises.’ Mitchell’s tank zigzagged between the trenches and turned left. His gunners fired several rounds without scoring a hit. Then came the sound of hail on a tin roof, accompanied by showers of splinters that rattled off their helmets. The Germans were using machine-guns with armour-piercing bullets. The Mk IV continued to dodge, the gunner on the left side, one-eyed as a result of the gas, firing often but still hitting nothing. Near Cachy Mitchell saw the two females, limping away with great holes in their sides. Another swing nearly brought his tank into a trench manned by our own troops; an armour-piercing bullet went through both legs of a Lewis gunner. The 6-pdrs still banged away, scoring many near-misses but no hits. Mitchell took a desperate decision. He brought his tank to a standstill in order to give his gunners one last chance before they too were scuppered. The one-eyed gunner scored three bulls in rapid succession. The monster halted, keeled over and its crew emerged through a door.

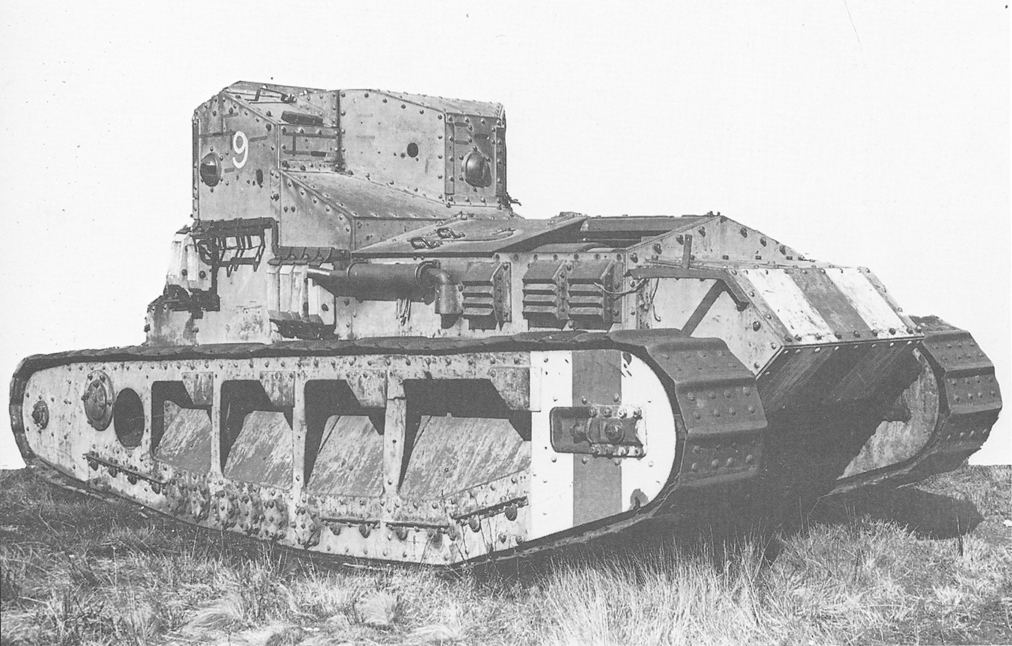

Another Whippet. Red and white stripes were used for identification after the Germans began to use captured machines.

The Lewis gunners gave them a drum or two for luck and then they went in search of the others, the 6-pdrs firing case-shot – the modern version of grape rejected by the War Office in 1916 – into the German foot. The German tanks, seemingly, had had enough; one by one they backed away and made off. Mitchell’s troubles were by no means over. A German aircraft bombed him from less than a hundred feet, blowing the tank clean off the ground. ‘We fell back with a mighty crash, and then continued our journey unhurt.’ A few minutes later they dropped into an unobserved shell hole; the driver quite rightly revved up the engine and, just as their nose was protruding, it stalled. Every German gun within miles seemed to concentrate on them. At such an angle all the efforts of the crew to swing the huge starting handle got them nowhere. The driver, well trained at Wool, did the only thing left; he allowed the tank to run back in reverse, let in his clutch and the good Daimler engine started up again.

As they climbed out Mitchell saw that the German infantry were waiting for him and were about to attack with bundles of lashed grenades capable of blowing off a track. Then he saw something more cheerful: ‘Seven small Whippets, the newest and fastest type of tank, unleashed at last and racing into action. They came on at six to eight miles an hour, heading straight for the Germans, who scattered in all directions, fleeing terror-stricken from this whirlwind of death.’ The Whippets, manned by twenty-one crew, routed some 1200 Germans, killing at least 400. A fourth German tank appeared but did not linger.

Nemesis followed hubris. A shell finally hit a track and blew it off. No 1 Tank of the 1st Section of A Coy had got its quietus. It was a glorious swan-song for the Mk IV. Never were decorations – Mitchell got an MC, his sergeant an MM – better earned. The German tank, ‘Elfriede’ by name, was salvaged with much difficulty. It carried a crew of eighteen but, apart from the luxury of a sprung track, it had nothing to teach the British designers.

A few days later the Mk Vs began to come along in numbers and the penny-farthing era was over. Factory workers, put on their mettle by the losses during the retreat, had been working as they were not to work again until 1940. New Mk Vs had been piling up and were now being shipped across as fast as could be managed. It was just as well. Apart from the Whippet companies the Tank Corps had almost ceased to exist.

The Landship conception was not yet history. Lieut Mitchell, captain of HMLS A1, solemnly and in due form submitted a claim to the Admiralty for prize money, he and his crew having captured SMLS Elfriede. Their Lordships, never over-swift to know that their legs were being pulled, passed it to the War Office. The reply does not say in so many words that Landships had ceased to belong to the Navy. It merely asserts that there was nothing doing, ‘there being no funds available for the purpose of granting Prize Money in the Army’.