ON 27 MAY THE GERMAN ARMY enjoyed its last success of the war. Led for the first and only time by tanks of its own it smashed through on the Chemin des Dames against some very indifferent French generalship. Five battle-worn British Divisions, sent there for a rest, formed the hard core of the defence. The thirteen-mile advance drew more salients on the map, as such advances always did, before the momentum flagged. The next assault, in mid-July, though it employed the biggest concentration of guns ever heard before and probably since, was a demonstrable failure. Even the mighty German Army could not now win the war by the old methods, no matter how large they might be writ. By midsummer the pendulum had reached the end of its swing and began to move in the opposite direction.

May and June were busy months for the tanks. Every battalion, except for some in Baker-Carr’s First Brigade, was now equipped or equipping with Mk Vs, Mk V Stars or Whippets. A few even bigger troop carriers called the Mk V Two Stars began to appear, though none came in time for the last battles. In addition a battalion of armoured cars arrived. This owed nothing to memories of Samson at Dunkirk but came into existence almost by accident. The Imperial Russian Government had ordered a number from the Austin factory. They bore little resemblance to the elegant converted Rolls-Royces used by Samson and T. E. Lawrence. The Austins were more plebeian, solid-tyred, weighing just under six tons and capable of 18 mph flat out on a hard road. Behind the driver’s cab stood two turrets, closely resembling great armoured dustbins each with a Hotchkiss gun poking out of it. The revolution in Russia left them on the hands of the British Government which decided that a use could be found as auxiliaries to the Tank Corps. Events were to show that the decision was amply justified. When the time came it was the 17th (Armoured Car) Battalion that led the British Army across the Hohenzollern Bridge into Cologne. But much was to happen before that memorable day arrived.

The main thrust of the British-Canadian-Australian-New Zealand Armies remained, on its southern flank, in the capable hands of General Sir Henry Rawlinson. His last personal experience of tanks had been almost exactly two years before and in almost exactly the same place. In 1916 he had been little impressed by them; in 1918 he was a convert, with all a convert’s zeal. His plans for hitting the Germans as they had never been hit before depended largely upon the new arm.

There were others yet to be converted. Since Bullecourt no Australian soldier had ever spoken of tanks but with contempt and loathing. This was hardly remarkable. Bullecourt had been the only battle in which they had lost many men as prisoners. All the same, before offensive operations could begin the Australian Corps would have to accustom itself to new ways. Their commander, Sir John Monash, was a civil engineer in private life and he saw the potentials of the Mk V and the Whippet more clearly and sooner than did most men. With his cordial encouragement Tanks and Diggers met again in order to get to know each other better. They were not so much demonstrations as parties. Courage’s Fifth Brigade put its Mk Vs through all their tricks, allowing the Australians to travel on them and even on occasions to drive. Then challenges were issued. Let the Australians prepare the strongest works they knew how to make and the tanks would set about them. Wire, trenches and redoubts were all flattened as a man grinds his boot heel into a wasp’s nest. Australia, ever a sporting nation, admitted the bet lost. From then on Five Brigade and the Australian Corps worked as one.

There were other little rehearsals during June. Stern, with his French and American colleagues, was working hard to build an Allied Tank Army. For this to become a reality the three armies concerned must learn each other’s ways. There had been a few chance-medleys at the end of April where French formations had found themselves encadred with the remains of British tank Battalions and the crews had earned much praise in little scrambling fights. The Armoured Car battalion first saw battle with the French First Army on 10 June at Belloy. Five females of the 10 th Battalion took part in a night raid – the first in which a tank was featured – at Bucquoy on the same day. The American 301st Bn, equipped with the latest Mk V Stars, trained at Wool and on arrival in France became part of the tank force of the British IX Corps, of Chemin des Dames fame.

The Hotchkiss gun which all tanks now carried was better for its purpose than the Lewis but efforts were once more made in June to obtain the best light automatic of them all. The Marquess of Salisbury, in a Lords debate on the 6th, said that he had tried out the Madsen and found it to be ‘enormously superior to any other gun in existence’. Lord Charles Beresford, who had seen the Gardner jam when the square broke at Abu Klea, called it ‘the most wonderful machine of its kind ever invented’ and Lord Moulton, most scientific of Peers, pointed out that its construction was so simple that stoppages simply did not occur. This could never have been said of any other machine-gun, not even of the Vickers itself. More tests had been carried out in May but in spite of all efforts no more could be got out of Denmark. It was a great pity, for this was the perfect tank weapon.

Rawlinson and Monash, men who got on well together, worked out details for a curtain-raising operation before the power of the Allied armies should be fully extended. It was not all that important to drive the Germans from Hamel, a short walk from Villers-Bretonneux, but it was as good a place as another for a dress rehearsal. This is strange country, a little to the south of the canalized Somme with the marshes stretching away from the bank. It is curiously up-and-down, little chalk ridges and little chalk depressions tossed about haphazard. Local people call it ‘the silent land’ and certainly the acoustics are freakish. In many spots a noise made nearby can hardly be heard though it can be picked up loudly half a mile away.

Since the attack was planned for 4 July Rawlinson decided to use, as well as tanks and Australians, the US battalion that had been sent to be trained by Fourth Army. When forbidden to do so, he turned a deaf ear. The plan, conceived mainly by Monash, depended almost entirely upon that forgotten element, surprise. On the first night of July a flight of RE8s, a particularly noisy kind of aeroplane, flew up and down in order to drown the sound of tank engines. Sixty Mk Vs moved furtively into position, forty-eight fighting tanks for the first stroke followed by a dozen more heavily laden with everything an infantry soldier could want. At 3 o’clock on a summer morning they moved off, the infantry leading. Every one of Ricardo’s engines ran as sweetly as a crew could wish. Two aircraft circled overhead, watching every German movement. As the barrage came down, so close that men could almost lean on it, tanks and infantry went in together, sometimes one ahead, sometimes the other. Only the German machine-gunners, the best men the Kaiser had, stayed to fight it out; it was a one-sided business. The Mk Vs used little ammunition but, with their superior manoeuverability they crushed the nests, crunching them into the ground as they turned and turned again on top of them. Only five machines were damaged and all were rescued. The Tank Corps losses amounted to thirteen wounded. The Australians were as pleased with the tanks as the tank men were captivated by the splendid dash of the Diggers and the Doughboys. More than 200 machine-guns were squashed, 1500 prisoners shambled off to the cages and the Australians unpacked their stores. Later the RAF, for the first time ever, dropped further supplies of ammunition. Another shape of things to come; General Slim’s Fourteenth Army, twenty odd years later, made it standard practice.

Hamel, though on a much smaller scale than Cambrai, was technically far in advance. After 4 July battle plans did not end with ‘And, by the way, you’ve got some tanks in your sector. Mind you, they probably won’t turn up’. Henceforth tanks would be reckoned as reliable as artillery, machine-guns or anything else. Mr – later Sir Harry – Ricardo and Major Wilson had good cause for pride.

Next, after Hamel, it was to be the turn of General Estienne’s Frenchmen. A fortnight after Hamel 375 of the little Renaults burst out of the forest of Villers-Cotterets, the spearhead of Mangin’s eighteen divisions that were to fight the second Battle of the Marne. They were undeniably funny-looking little objects, especially when set alongside a Mk V, but each carried either a 37 mm gun or a light automatic in a rotating turret. The Germans did not find them amusing. With no Hindenburg Line to be crossed and the going easy, the Renaults had a field day. France, hard hit and shorn of some of her fairest land, was at last effectively striking back and the savage Mangin was just the man to lead her soldiers. The presence of strong, fresh American divisions, each double the size of a normal one, heartened all hands. Germany had nothing similar to cheer her tired men.

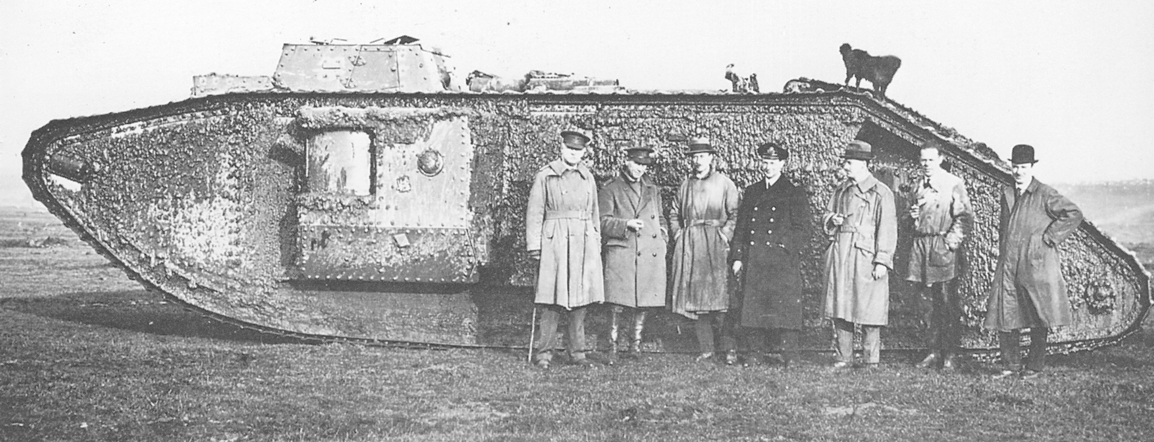

Demonstration of fire and movement aided by Mk V Star.

On 23 July there came an interesting combined operation. At Mailly-Raineval, hard by the little River Avre, stood several troublesome German batteries. The French intimated that some tanks would be helpful to the four battalions they had detailed for the assault. Brigadier-General Courage was despatched with the 9th Battalion to see what could be done. It turned out to be much like Hamel but without the opportunity of the careful preparation that Monash always demanded. The positions were taken and the batteries smashed, but at a price. Of thirty-six tanks engaged fifteen were knocked out by shell-fire and fifteen more so knocked about that they were beyond salvage. Almost worse was the loss of a Mk V, hit while trying to tow away a captured gun. It may have been damaged beyond repair for, unlike some of the Mk IVs taken at Cambrai, it was not seen again under the Iron Cross. The French were well pleased; 1,800 prisoners, five field pieces, forty-two trench-mortars and 276 machine-guns were a haul not to be despised. General Debeney issued a very handsome ‘Ordre du Jour’ and presented the 9th Battalion with the badge of the French 3rd Division, to be worn on the sleeve evermore.

Baker-Carr’s First Brigade, in Sir Julian Byng’s Third Army, was not engaged in any of these affairs. To his chagrin he still had only Mk IVs, though Mk Vs were beginning to dribble in. Nor was his life easy, for his Brigade was in IV Corps area. ‘Uncle’ Harper, ‘after his experience with tanks, first at the Arras battle, then in the Third Battle of Ypres, and finally in the Cambrai battle, felt that he knew more about tanks than any living man and, at his Corps Conferences, had no hesitation in saying so. “I know far more about tanks than anybody, Baker,’ he usually began, “and this is what you are to do.” He then proceeded to outline a scheme which was utterly impossible to carry out. Such trivialities as time and space were completely ignored and the tanks were ordered to dash about a battlefield like a terrier in a cornfield catching rabbits. Only on one occasion did he prove obdurate to my arguments and I was forced to appeal to higher authority.’ Baker-Carr and ‘Uncle’ Harper had by no means seen the last of each other, quite apart from the incident when one of the Americans, sent to First Brigade for instruction, amused himself by loosing off a captured German machine-gun and nearly decapitating a senior member of IV Corps Staff. Baker-Carr submitted meekly, for him, to a cursing on the subject of ‘your barbarians’. Yet everybody still liked ‘Uncle’ Harper.

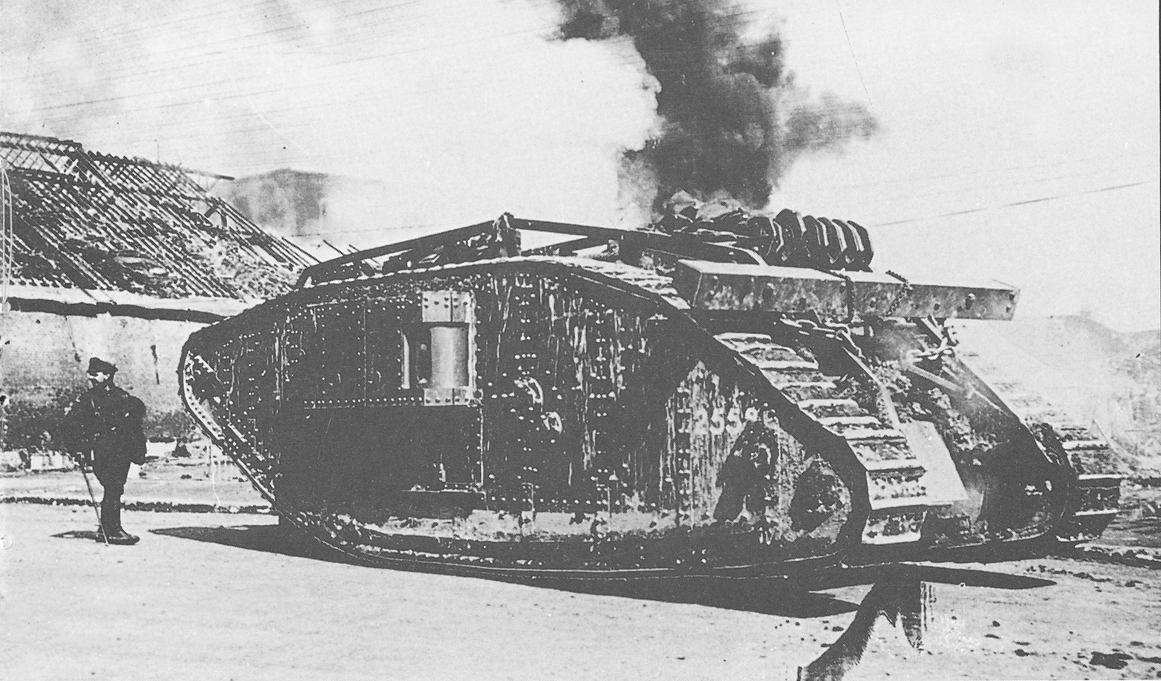

Hamel, 4 July, 1918. Australians with a knocked out Mk. V.

Sir Henry Rawlinson mulled over his plans for the first punch in the battles of the hundred days which would bring the war to an unexpected end. Under his command was a big and highly efficient Armoured Corps: fourteen battalions, two Whippets and the remainder all Mk V or Mk V Star, plus the Armoured Car battalion and a company of gun-carrying tanks converted for the occasion to supplying infantry with all kinds of explosive; Tank Salvage Companies followed close behind them all. The Fourth Brigade, under Brigadier-General E. B. Hankey, would go to the Canadian Corps; Courage’s Fifth, of course, would stay with the Australians. One battalion, the 10 th, should belong to Butler’s IIIrd Corps and the remainder, Hardress-Lloyd’s 3rd, which included the two Whippet battalions, would help the Cavalry Corps in yet another of its attempts at a break-through. The odd unit, the 2nd battalion, would remain in GHQ Reserve.

Sir Henry Rawlinson was the embodiment of the Old Army. The thirty years of service now behind him had taken him to India as ADC to Lord Roberts, chasing dacoits in Burma, up the Nile with Sir Herbert Kitchener and to Ladysmith with Sir George White. He had commanded a Mounted Infantry regiment in South Africa; years later, after a visit to Russia, he had written to Lord K saying that ‘my old 8th MI could run rings round any number of Cossacks’. More recently he had been in every battle since First Ypres, beginning as the first Commander of IV Corps and his experience was unmatched in the BEF. His meticulous preparation for the battles that began on 8 August could hardly have been bettered. There was, for one thing an elaborate deception plan involving dummy tanks, British troops far from Amiens masquerading as Australians and Canadians, and spoof wireless traffic; all expedients to be repeated in 1944, with variations. The tanks this time worked to a plan and not as mere gate-crashers. The distribution was deliberate, the bulk of them on the south of the Somme where the going was easy and only a few in the far more difficult north.

Every tank officer was, at last, given precise orders, not padded out with masses of typed matter with which he had nothing to do. Most of them were taken to examine from hilltops the places where they would be doing their work, and the infantry with whom they would be cooperating knew it just as well. It was a kind of mutual benefit society, the tank men saying, in effect, ‘I will make you a path through the wire and squash any machine-guns that may try to knock you about’; the infantry reply was, ‘You do that and I will keep you heading in the right direction; what is more, my snipers and Lewis gunners will take care of any antitank guns that may want to take a hand.’ The gunners would drop their barrages at such times and places that German artillery would not be in any shape to interfere. There was no need now for the man metaphorically carrying a red flag to walk in front. More often than not a couple of infantrymen travelled on the roof to do any guiding needed. It worked very well.

The attack, of course, was not yet on the main Hindenburg position. This battlefield was an old one for both sides, the one from which the Fifth Army had been driven in March. It held no secrets from the attackers, though the Germans had made the most of everything available to them.

Early on the morning of 8 August Rawlinson’s guns, all 2,000 of them, bellowed out as one. Infantrymen and Mk Vs moved forward through what General Maurice calls ‘a friendly mist’, with the RAF weighing in from above as opportunity offered. The German army, while still an uncommonly good one, was not that of 1916. By the same token, nor was the British; it lacked some of the dash of the first Somme battles, but it was a lot more artful. This was just as well, for the supply of men was running very low. It is often said that the effect of the tanks on the Kaiser’s war was mostly moral; how wire is flattened and machine-guns screwed into the ground by moral suasion is not explained. All the same it is more than a copy-book heading. Ludendorff himself admitted later that he had underestimated the tank; probably the capture of the early marks had done the Allies more good than harm. The Germans did begin a tank-building programme of their own but it came too late. Only fifteen Elfriedes ever turned up and they did not prove formidable.

There is no doubt but that by August the bulk of the German infantry when confronted by tanks or rumours of tanks quickly developed the condition known to soldiers as ‘wind up’. The turn of other armies was to come years later. Anti-tank weapons were strangely slow in arriving. Oddly enough it was the British Army that laid the first mine-fields, very ad hoc and made out of artillery shells; the only German anti-tank weapon apart from the field gun was an enormous rifle firing large-calibre bullets; nobody fancied using it for the kick would dislocate a man’s shoulder. Large numbers were captured, mostly unused. It was nearly as futile as the Boys rifle of a generation later.

The battle of 8 August went much like a sand-table exercise. Ricardo’s engines purred happily, Wilson’s epicyclic gear did everything its inventor expected and bullets rattled off Tritton’s strong hulls.

Only the Whippets had nasty experiences. The idea of combining them with horsed cavalry was not clever; possibly the old forces were too strong even for Sir Henry Rawlinson. On the approach march the tanks could not keep up with the horses, fresh after long inactivity. Once the start line was crossed and a machine-gun or two began to fire, the horses could not keep up with the Whippets. The result was that two valuable battalions were kept from doing what they had been designed to do simply because of the presence of masses of incongruous animals. The armoured cars, however, had a field day. There is an excellent Roman road running in a dead straight line from Villers Bretonneux to Peronne. As there seemed no obstacles on it after the tanks had moved some felled trees, the cars drove along the road, catching up with masses of fugitives who were running away from the Australians. The cars sped them on their way with machine-gun fire. One section got as far as Framerville, nine miles from the front line, caught a German Corps Headquarters at an unguarded moment in a farm-house, grabbed every document in sight, shot up the Staff officers, the Corps Commander being absent, and drove back home with valuable booty – complete, detailed plans and photographs of the main Hindenburg position.

It was not all like that. A company of gun-carrying tanks, converted for the occasion to supply tanks, had been hidden in an orchard at Villers-Bretonneux where it was loaded up with petrol, mortar bombs, gun cotton and the like. On the evening of 7 August a single shell hit one of them and set it on fire. The flames could not be hidden and for several hours German guns searched the area. Every tank was destroyed. Then the shelling stopped. Nobody knew how it had happened.

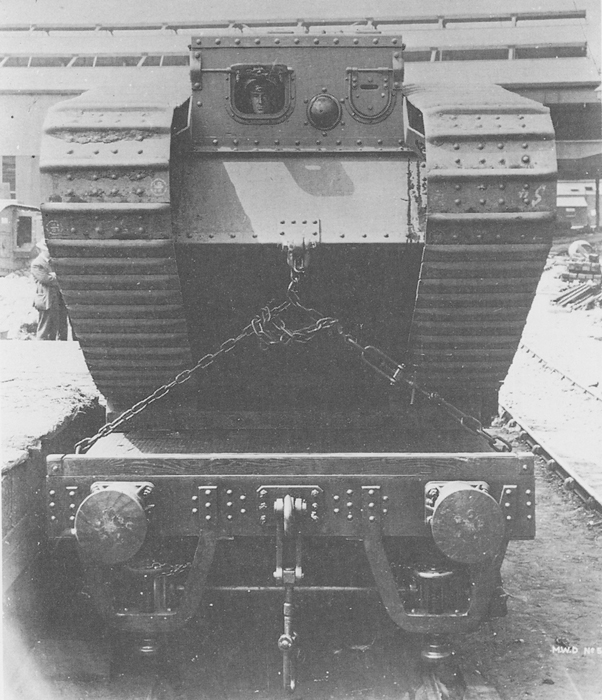

Mk V Two Star with Majors Buddicum and Wilson and Mr Ricardo.

Nor should the impression be given that 8 August was a walkover. When the sun dispersed the mist and a fine warm day followed, the German gunners got to work. A good many tanks were knocked out after the first four hours of the battle, the Canadian sector being hardest hit. Nevertheless the third and last line of objectives, the Red Line, had been everywhere reached before the day was over. Those of the Whippets not tied to the cavalry had made piratical raids well into the rear areas. Lieutenant Arnold and his ‘Musical Box’ are among the Tank Corps immortals. Nor was it only the German gunners who held back the tanks from doing all that they had planned. The defective ventilation system of the Mk V made ovens of them as the sun rose. One report, from a battalion with the Canadians, says that, ‘With the prolonged running at high speed the interior of the Tank rapidly became unbearable through heat and petrol fumes and the crew were forced to evacuate it and take cover underneath. At this moment two of the crew were wounded, one was sick, one fainted and one was delirious. Fortunately, before the enemy could take advantage of the lull, two Whippet Tanks and a body of cavalry came up and the enemy in the valley began to retreat over the hill.’ Around Beaucourt-en-Santerre nine out of eleven tanks of A Company 1st Battalion were knocked out by a field battery firing over open sights.

Mk Vs of 10th Bn. Tank Corps with New Zealanders. Grevilliers, 25 August, 1918.

The Mk V Star had proved not up to the job for which it was designed. Passengers unaccustomed to the fumes and motion became so very sick that, wherever possible, they were allowed to get out and walk behind. When fire compelled them to get back in they became so ill as to be useless for anything for the next couple of hours. Stern and the Americans were working on this. The Mk IX was now on the drawing board. In the Spring of 1919 hundreds of them would be carrying fifty men each in Pullman car comfort by comparison with that offered by the Mk V Stars. That, at any rate, was the hope. In sober fact, on the authority of Wilson, the machine designed by d’Eyncourt and Lieut Rackham, ‘developed considerable mechanical troubles and only a few were completed before the Armistice’.

With the Mk IX the wheel would come full circle. The very first report of the Landships Committee, delivered to Mr Churchill in June, 1915, had told how ‘these Landships were at first designed to transport a trench-taking storming party of fifty men with machine-guns and ammunition; the men standing in two ranks at each side and protected by side armour of 8 mm thickness and roof armour of 6 mm. These vehicles were 40 feet long by 13 feet wide.’ They had never got beyond the stage of working drawings, much modified as time went on and the near impossibility of the plan became clear. Now, in little more than three years, the thing had been done and the first intentions of the founding fathers had taken tangible shape. Until the Mk IXs appeared, however, the Mk V One and Two Stars had to do the best they could. More often than not they were used either as fighting tanks or as freight rather than passenger carriers. This was the best use that could be made of them; a Canadian soldier described his journey in one as a ‘sort of pocket hell’.

Men of 5th Australian Brigade with Mk V Star. 8 August, 1918.

The next morning, the 9th, found 155 tanks still going about their business. It was another successful day, even though it cost eight machines to the German artillery at Lihons and five more around the awkward Chipilly spur to the north of the river. ‘The Whippets’ action, in as far as they were billed to act with the cavalry, was disappointing. By some fault of liaison they were kept too long at Brigade Headquarters,’ said Williams-Ellis. By 10 August the number of effective tanks was down to eighty-five, of which twenty-five were to receive direct hits during the day. On the nth only thirty-eight, each in dire need of overhaul, went back in. On 12 August the last six were engaged and before the day was out the Tank Corps had been withdrawn in its entirety.

Death came suddenly and messily to many tank men during the sunny August days. Quite apart from those who had to be buried in sacks there were men decapitated and men roasted alive in addition to the Reconnaissance Officers who went ahead and were killed in the customary ways. Most of the damage was caused by a single battery in a wood near Le Quesnil. As the French had not kept up with the Canadian right a gap existed from which the Germans could catch the tanks in enfilade as they crossed the Sancerre plain. They did not waste their opportunity. Word spread among the infantry that life in the Tank Corps was not the reserved occupation that some people thought; all the same volunteers still came forward. They were needed. By the autumn Elles was obliged to report that he had tanks enough to see him through the year; it was shortage of trained crews that would limit his operations.

Sir Douglas Haig, though not the expert ‘Uncle’ Harper was, had learned much about what tanks could and could not do. As the line was coming up to the formless moonscape of the old Somme battlefield, he pulled them out and sent them north of the river to help Sir Julian Byng take Bapaume. Baker-Carr’s First Brigade, already in Third Army, still had a fair number of Mk IVs on his strength, the last ones left as fighting machines. The morning of 21 August promised a fine sunny day, the usual mist hanging low until close upon noon. Many a tank crew member wished it would freeze. It was wretchedly bad luck that conditions inside Mk Vs and Whippets were so affected by heat for this was about the first long bout of decent weather since Mons. One hundred and ninety tanks of all three kinds took part in the battle for Bapaume. The moral effect was satisfactory, large bodies of enemy appearing only too anxious to be packed off to the prisoner-of-war cages. The first line fell with almost suspicious ease. Then at about 11 o’clock two things happened at once. The mist rose and the leading tanks found themselves on or near the embankment of the railway from Albert to Arras. To this convenient line the German artillery had withdrawn some batteries of field guns for the express purpose of shooting down the tanks as they appeared. As the sun broke clear their targets materialized as if done on paper with poster paints. Each machine came under a hurricane of fire, a hurricane shared by the infantry following along behind. Most of the thirty-seven tanks that reached the railway line were knocked out on it. Had the mist lasted for but another half hour they would have been able to deal with the enemy gunners themselves; as things fell out, it became necessary to whistle up the RAF. Machine-gun fire and small bombs soon saw the gunners off, but they had done their work.

Every post-battle report again told of how heat and fumes were far more serious enemies than anything the German Army could produce. Men, even the most hardened, passed out completely and on resurfacing found that their memories had gone; most of them recovered after a few hours but Mr Ricardo had made a bad error in believing the exhaust-covering and internal fan, admittedly makeshifts, ‘served its purpose’. It did so only for the time needed to warm the engine up nicely.

Squadron 20 bore responsibility for testing and, with all their accumulated experience, they had found nothing to worry about. Which goes to show that the only worthwhile test of a weapon of war is its performance in war. Only under battle conditions was it discovered that once the exhaust pipe had reached a certain degree of heat the joints warped and neat carbon monoxide fumes continued to be pumped inside the hull. As a form of suicide this has long been popular; even the most salted tank crews could endure it for only a little while.

For all its excellent qualities the Mk V was still not good enough. Even if Squadron 20 had reported upon this joint in the armour, as it may well have done privately, it would have made no difference. The Mk Vs had got to be used; there were no others.

On 23 August ‘Uncle’ Harper again demonstrated his tank expertise. Late in the morning, says Williams-Ellis, ‘some of the Whippets of the 6th battalion were operating with the infantry of IV Corps to the east of Courcelles. It was suddenly noticed that the artillery barrage table had been altered, and that the rate of progress of the barrage was now 100 yards in four minutes, that is to say considerably slower than had been originally intended. The Tanks were therefore obliged to manoeuvre and wheel about in order to let the barrage keep ahead. They were constantly under anti-Tank gun fire at this time.’ It was in spite of, rather than owing to, ‘Uncle’ Harper’s staff work that the Whippets got themselves out of a nasty scrape and went on to give strong help to the taking of Achiet-le-Petit, squashing a number of machine-gun positions on the way.

Still there was no rest for tanks or crews. The small numbers of both left fit for duty meant that it was the same people who went back in time after time; it says a lot for the mechanical reliability of the new machines, despite their limitations, that they were able to keep going for so long. Stern says that the endurance of a tank in battle was reckoned to be three days. Many of them, though crying out for overhaul, had been at it for twelve. By the time for the attack on the Drocourt-Queant Switch, hard by the old Arras battlefields, a hundred new machines had arrived. They were just in time; the old ones were very nearly played out.

Though the scent of victory was breast high for all the advancing armies nobody was under any illusions about what lay ahead. So far the defences they had penetrated had all been the usual kind of field work. The next would be very different. In the Spring of 1917, under the pressure of the battles of the Somme and the Ancre, the Germans had made a decision of first importance. For probably the only time in history a communique saying that ‘our troops had retired to prepared positions’ meant exactly what it said. The Hindenburg Line – called that only by the British – was no scambling trench and wire system, put up by fatigue parties in the dark, usually under fire. It was an elaborate piece of civil engineering carried out under peacetime conditions by non-combatant labour, mostly Russian prisoners and impressed civilians. It had all the mystique of the Maginot and was, for its day, just as effective. Acre upon acre of blue-gleaming barbed wire of the thickest kind gave the boldest observer cause to think. On the front of the old Arras battlefield lay a substantial outwork, begun just before Allenby’s battle and designed to link the Hindenburg position around Bullecourt of awful memory to the old La Bassée-Lens system. In April, 1917, in its unfinished state, it lay just beyond the furthest point reached by any part of Third Army. By August, 1918, it was complete in every detail.

Under Sir Julian Byng the Third Army stormed it in the course of a single day. The Canadians, who practically owned Vimy Ridge, 63rd (Royal Navy) Division and 52nd – lowland Scottish Territorials brought from Palestine during the German Spring offensive – moved off on the morning of 2 September covered by a barrage of a million shells. Eighty-one tanks took part, about forty of them heading for the Switch itself. What the German Army called Tankschrecken – ‘Tank Funk’ – had been spreading since 8 August almost as widely as the influenza that affected all armies. The attackers moved off at 5.30 am; by lunch time all was over bar some clearing up. Further south the Australian Corps, with an audacity that only that irrepressible formation could have managed, chased the Germans from the almost equally impregnable Mont St Quentin.

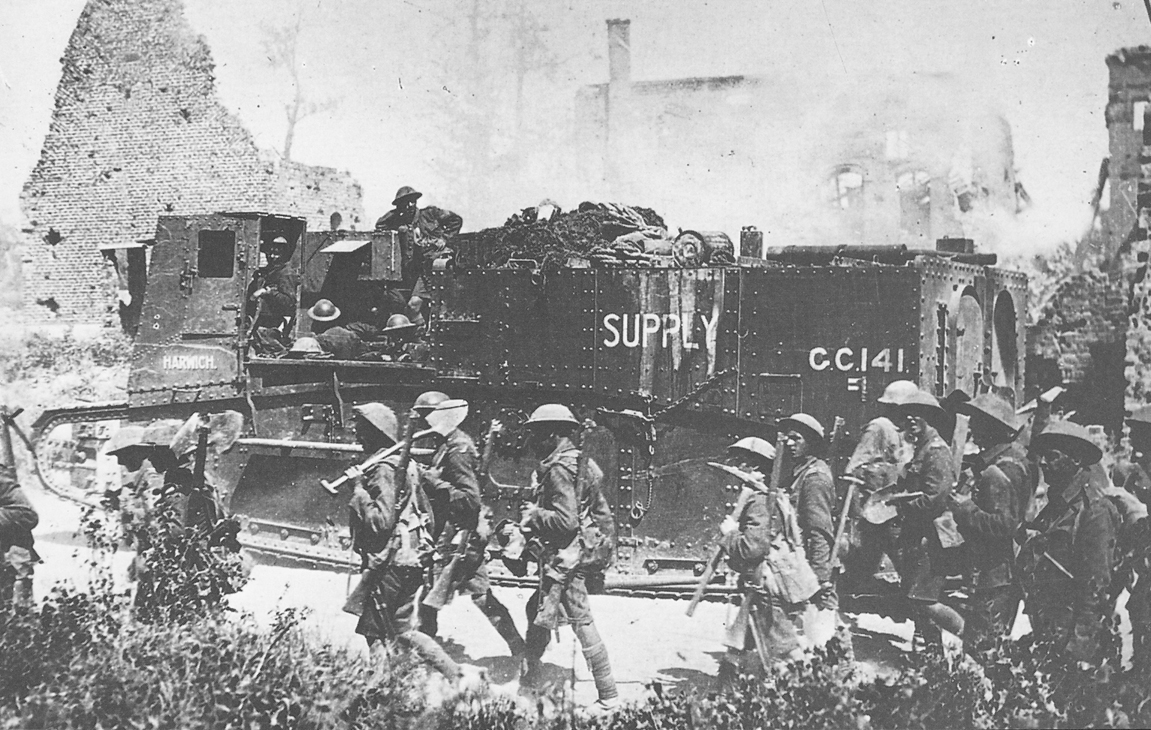

Supply Tank at Bucquoy, 19 August, 1918.

Though the cry was now going up in France for more tanks, the prospect of their arrival in a continuous and ever growing stream was far more remote than anybody realized. During the victorious month of August James Borrowman Maclean was appointed Controller of the Mechanical Warfare Supply Department with the right of direct access to Mr Churchill. Maclean was a professional engineer from Clydebank who had already served the Ministry as Director of Shell Production and Controller of Gun Manufacture. No man knew better than he the ins and out of the entire munitions business and he took up his new post with a grim suspicion that all was not well with tank production. He found matters far worse than he had expected.

The official estimates of production of all kinds of tank gave figures of 203 for September, 1918, rising to 747 in the following April. These estimates had already been vetted by Mr (later Sir Percival) Perry who reckoned them on the high side for the first few months but pessimistic when 1919 should arrive. Maclean got down to them in detail. His conclusion was that, thanks to a falling labour force and a great deal of of muddle, the two sets of figures were wildly optimistic. His own showed that at best we could hope for only 2,320 by April as against an official estimate of 4,334. Of the 900 Mk IXs ordered in September, 1917, not a solitary one existed; nor did any of the Mk VIII hulls promised to the Allied Commission. 250 Medium Bs had been bespoken at the same time; there was just one sample machine finished.

The blame was placed almost entirely upon the Ministry. Two firms, one of them Beardmores, came in for heavy criticism because they had piled up armour-plating beyond their machining capacity. Maclean calculated that ‘over 5,000 tons of unmachined plate were lying about the country’. D’Eyncourt concurred with the report and Tritton had something to add to it. In his evidence to the Royal Commission he asserted that ‘Many months were lost in the construction of these machines through the non-delivery of parts by the Mechanical Warfare Supply Department. This Department undertook to supply the engines and gear-boxes and they fell twelve months into arrears with gear-box deliveries.’ In a letter to the MWSD dated 31 August he complains that ‘The Lannoe Committee orders smoke bomb equipment for the Hornet. The Edkins Committee says they are not wanted’. What was he to do? It was not the first letter of its kind. Nor was that all. A report from the Chief Testing Officer of Squadron 20, dated 11 July, says that ‘The failure of a large number of the sprockets and their replacement is by far the most serious matter the Tank Corps have now to face.’ He blamed it on sheer bad workmanship.

Maclean took over in the first week of August, just as the tanks were inflicting on Ludendorff his ‘Black Day of the German Army’. His first letter to Mr Churchill says that ‘I believe that a continuation of the policy which came to an end in August would have resulted in a complete cessation of deliveries before the end of this year.’ Then he took the Department by the scruff. Wilson, expressly freed from any criticism, gives some figures. By the end of the war exactly seven Mk VIIIs had been made here and ‘a few in the US’. Medium Bs numbered forty-five; Medium Cs thirty-six. In all 2,696 tanks of all kinds had been completed. Maclean speaks of the Medium D – the gleam in Fuller’s eye – in a letter to the MWSD written in January, 1919. ‘Owing to a certain amount of Departmental jealousy (it) had not benefited by the experience of the main design staff.’

German Tanks. ‘Mephisto’, an A7V captured by the Australians..

It all sounds so very remote from Fuller’s ‘Tank Programme 1919’. For what he calls ‘the decisive attack’ he would need 7,700 fighting tanks, plus 3,282 administrative ones (‘Carriers for 80 Divisions, 1,600’). In all he required, counting reserves, 18,000 tanks with 1,500 trains to bring them near the battlefield. They were to be provided in equal thirds by Britain, France and America. Maclean’s comments would have been worth hearing; the Scotch are not reckoned to have an outstanding sense of humour. Fuller, rather interestingly, talks of the need for ‘thousands of tanks, both light and heavy, ranging from 2 mph to 8 mph’. No talk of the Medium D and 20 mph yet awhile. ‘When can we get 20 mph Tanks?, is Item 13 at a War Office Conference that took place on 26 June. No answer appears in the record. The question was purely rhetorical.