LET US NOW CONSIDER how matters stood at the moment when Marshal Foch was laying down armistice terms to a German delegation in the railway siding at Compiègne. In accordance with custom, information about the enemy must come first. That Germany was in a bad way was beyond argument. Had it been otherwise no senior officer of that proud Army would have been present in Foch’s Pullman straightly admitting that they were beaten. They had been driven out of their strongest fortifications; quite apart from their dead and wounded there were not far short of a million men missing or prisoners. The combined efforts of the Royal Navy and Admiral Sim’s American ships had decisively broken the U-boats. In the air the Royal Air Force, the French and the small but growing US air service had something like complete superiority. Even more serious than these serious things was the state of affairs in the Fatherland. Four years of blockade had done its work; actual starvation had not yet come, but it was coming.

The black side was black enough, but there were lighter patches. There are, naturally, many resemblances to 1945, but one factor is missing. No great Russian armies were closing in from the East. Had the Kaiser not panicked, it was entirely possible that a stand might have been made even if it had to be on the Rhine. New weapons were on the way; the Siemens-Schuckert fighter aircraft with its 11 – cylinder rotary engine should have been capable of overcoming anything that the Allies then had; German chemists could still turn out poisonous gases nastier than ever; the fate of the 301st Battalion had demonstrated that tanks were very vulnerable to mines, even to makeshifts from mortar bombs, of which there were still plenty; the TUF machine-gun, added to small guns borrowed from the fleet and to ordinary field-pieces simply converted could have seen off most tanks. And there remained the High Seas Fleet, still capable, had it only the stomach for it, of forcing a naval engagement with some chance of success.

Sir Henry Rawlinson, better informed than almost anybody, had firm views: ‘It has been contended by some that the armistice was premature, that in another few weeks the German Army would have been forced to lay down their arms and surrender unconditionally. I do not hold this view. It is true that, insofar as the fighting troops of the Allies were concerned, a pronounced moral ascendency had been established in all the Allied Armies throughout the whole western front, and was daily increasing. Owing, however, to the thorough and systematic manner in which the Germans had destroyed all railways, roads and bridges during their retreat, it was a physical impossibility for at least the British Armies, and I think for any of the Armies, to continue their advance rapidly and in strength, and to immediately follow up their successes. Had they done so, they would have starved.’ Winter would not have improved their chances; whatever else the Germans lacked it was not time. Had their Generals possessed the determination to see the business out to the end, determination shown by Jubal Early in 1865 and Christiaan de Wet in 1902, they might have compelled a stalemate followed by a peace of mutual exhaustion. America and Bolshevik Russia would then have had Europe to themselves, with results beyond imagining.

Had the Allies been able to endure yet another winter their complete military victory was possible, even probable; but it was not a foregone conclusion. On the British side whole divisions had long since been reduced to cadres and more would have had to go the same way. Already there were far too many soldiers whose youth or middle-age made them vulnerable to a winter in the open, and that without taking any account of the influenza epidemic that was to kill more people world-wide than the war itself had done. To press on to victory it would have been essential to cut down infantry and artillery strength in order to build up a powerful armoured force. The great, unanswered, and unanswerable question is whether this could have been done.

A Mk VIII with British and U.S. officers.

Had the armistice been delayed by a single week, or had some misbehaviour by Germany vitiated it, General Trenchard’s Independent Air Force, based around Nancy, would have been capable of dropping 500 lb bombs on Berlin. No obvious military end would have been gained by thus punishing half-starved civilians, unless vengeance be reckoned an end in itself, but it would have brought war home to Germany as it had been to France and Britain. Here again it would be unwise to take success for granted. The new fighters in the hands of men like Hermann Goering before he got into bad company might have knocked down the Handley-Pages at their extreme range and have caused the business to be given up.

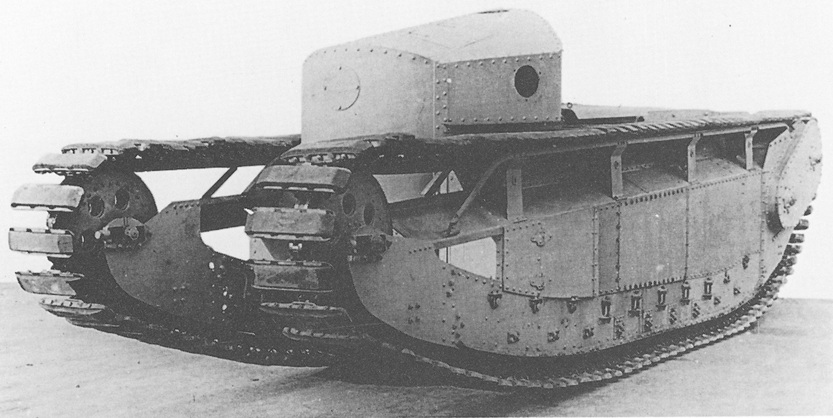

It was on 29 November that Stern, in his Paris office, received the cable from Stettinius for which he had been waiting and which told him that the International tank had passed all its tests. It was a very fine tank for its time, but it still had a top speed of only 6 mph and could travel only about fifty miles on a fill of 200 gallons. It weighed 37 tons, could cross a 14-foot wide trench and climb anything within reason. The armour was 19 mm thick. Ricardo’s engine in the British model and the Liberty in the American put out 300 hp. It should have been thoroughly reliable mechanically and far less exhausting to drive than anything that had gone before. All the same, to approach a strong German position, presumably mined, at 6 mph was not a thing to be taken lightly. Great numbers would be needed, as they would be with the British Mediums B, C, and D. Nothing could be hoped of Neuvy-Pailloux for some time to come. Most of the Internationals would have to come from US factories and even that great source of production had its limits. The arrangement was for 1500 to be made in the States while Neuvy-Pailloux would turn out the same number. When the American manufacturers ran into difficulties with armour-plate and guns it was decided to move the whole enterprise to France. Accurate prediction of when this mass of machines would be handed over to their crews was hardly possible even by late November.

Then came the master-question. Given that the machines were to arrive, where were the men to be found? In his famous memorandum of 5 March, 1918, Mr Churchill had made the proposal, acted upon twenty years later, of ‘putting most of the cavalry into tanks or other mechanical vehicles’. This made excellent sense, but time was against it. At a pinch men can be made into reasonable infantry soldiers in a few months. Grooms cannot be turned into mechanics and gunners in anything like so short a period. When he speaks of constructing ‘armoured vehicles of various types … to such an extent and on such a scale that 150,000 to 200,000 fighting men can be carried forward certainly and irresistibly on a broad front and to a depth of 8 or 10 miles in the course of a single day’ it sounds more like Mr Wells than the sober Minister. The war had reached a point much like that in South Africa after Lord Roberts had gone home convinced that all was over. It soon became clear that Wellington’s Peninsular Division was not the kind of formation needed for war on the veldt; instead of a number of miniature groups of all arms it became necessary to raise a completely new army made up almost entirely of horsemen. This had been done after a fashion, but it took a couple of years. To do the business again, making an infantry army into a mechanically propelled one, would be a much longer affair. And until such an army existed the idea of using cavalry tanks for raiding far behind lines, disrupting communications and smashing up headquarters, was a pipe-dream. Some of the elements existed, such as the armoured aeroplane that could defy ground fire and pick off anti-tank batteries; already the Tank Corps was working on machines pushing rollers that might be able to clear ways through minefields. The idea was sound enough, as the last stages of the second war were to demonstrate; but in November, 1918, it was not yet practical.

Fuller’s ‘Plan 1919’ is well known, with its emphasis upon using 20 mph tanks for raiding deep behind the lines and wrecking enemy headquarters rather than pushing the whole line forward as it had been pushed during the battles of the hundred days. It is difficult to regard this as more than a TEWT on the grand scale with a touch of Tennyson’s Locksley Hall for good measure. In the first place the plan of campaign would not be devised by the War Office but by Sir Douglas Haig and his advisers. It is far from certain that Fuller, a Staff Officer of only field rank and already known by his self-chosen adjective of ‘unconventional’, would have been asked for an opinion.

Mr Churchill put his point of view many years later in an article called Shall We All Commit Suicide? ‘Had the Germans retained the morale to make good their retreat to the Rhine, they would have been assaulted in the summer of 1919 with forces and by methods incomparably more prodigious than any yet employed. Thousands of aeroplanes would have shattered their cities … Arrangements were being made to carry simultaneously a quarter of a million men, together with all their requirements, continuously forward across country in mechanical vehicles moving ten or fifteen miles each day. Poison gases of incredible malignity … would have stifled all resistance and paralysed all life on the hostile front subjected to attack. No doubt the Germans too had their plans.’ They had. One of them was a delay action fuse, used to deadly effect in the last days, that could set buried mines to go off at any time from hours ahead to months. It came near to stopping all rail traffic. Mr Churchill had, on his own authority, ordered 10,000 caterpillar tractors from Henry Ford and he spoke of the Mk VIII as ‘the tank we are counting on for 1919’. He acknowledged the difficulty in finding crews, with men of fifty already called up, and suggested that the Navy and the Marines should provide the men ‘necessary to steer and manage the last 2,000 tanks to be completed before the battle’. Although he wished to see the Tank Corps raised to a strength of 100,000, he admitted that ‘you will have large numbers of these invaluable weapons without the men to man them’. Nowhere is petrol mentioned. Cambrai alone had used up a quarter of a million gallons. Every first war tank was what the Americans call a ‘gas-guzzler’.

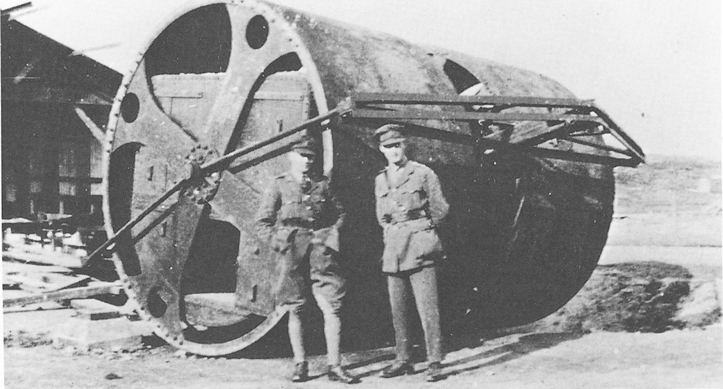

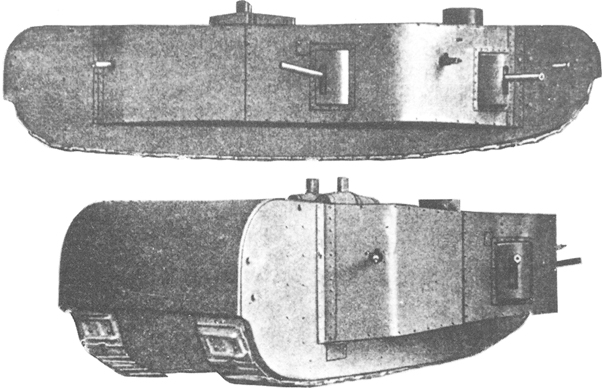

Above and opposite: The medium D Tank, Fuller’s ‘White Hope’ for 1919.

Both photographs are post-war.

Mr Churchill was at least planning from a known base, for the Mk VIII was nearly ready in prototype and its capabilities and its limitations were understood. Fuller worked on what must be called visions. The Medium B and C tanks were certainly improvements on the Whippet; from the crews’ standpoint they were great improvements, for the 100 hp Ricardo engine was more reliable than the Tylor and, for the first time, engine room and fighting compartment were separate. All the same they were still not good enough for lightning raids; their speeds were only slightly more than that of the Medium A and their radii of action small. Neither ever reached France, though a few were sent to General Maynard at Murmansk shortly before his force was withdrawn. He does not mention ever having used them.

Fuller’s plan was based on the Medium D, which did not exist. It was the brainchild of Lieut-Col Philip Johnson, a professional engineer and one of Searle’s bright young men at Bermicourt. He had begun experimenting in February, 1918, searching for something that would come up to the magic speed of 20 mph, and by October his plans were sufficiently advanced for him to be given a free hand. A Mk V was sent to his old firm, Fowlers of Leeds, where it was stripped of tracks, rollers, sponsons and much else. Johnson fitted what remained of the hull with new tracks of his own design. This consisted of an ingenious suspension system based upon pulleys, bogeys and steel cables; the old Tritton-Wilson plates were scrapped and replaced with a curious arrangement shod all the way round with wooden shoes. These were described as ‘expendable’, an apt enough word since, as soon as the machine gathered speed, they tended to fly off in a shower. The Medium D did not emerge in its final form until May, 1919; even then the unenlightened were sceptical about its queer appearance, saying that it looked as if it had just had a serious accident. It did indeed touch 20 mph in ideal conditions but whether it would prove battleworthy was much open to question. Only five were ever built and none went into service.

Model of a German 100-ton Tank. Never completed.

A Mk IV Salvage Tank, with the ‘electro-magnetic collector’.

A Mk IV Salvage Tank with crane jib.

The Army is often accused, not always unjustly, of preparing for the last war over again. Fuller prepared for the next but one. Anything said about the prospects of success for Plan 1919 can only be guesswork. It seems fair, however, to suggest that any grand attack undertaken that Spring would not have been based on anything dreamed up by a middle-grade British Staff Officer. Smashing up enemy headquarters was an obvious ploy and it could have been better carried out by the heavy bombers of the RAF, for the four-engined Handley Page 0/400 was in squadron service. The tank part of the business would have had to be entrusted to the Mk VIIIs, mostly American-manned and certainly not numbered in thousands. Foch would, no doubt, have retained his post but the decisions would have had to be those of General Pershing who was not a tank fanatic. He had only recently asked Haig for the loan of 25,000 horses. Fuller, one suspects, would have been ignored.

Even Mr Churchill was the Churchill of 1919, far removed in power from the great War Lord of 1940. He and Sir Douglas did not carry mutual admiration to excess. The CIGS, Henry Wilson, could claim that in him Mr Churchill detected signs of military genius but Sir Douglas loathed and despised him. Anything suggested by Mr Churchill, however inspired, would have been greeted with cries of ‘Gallipoli’ and rejected out of hand as a matter of course. A further imponderable was the great influenza epidemic of 1919 which killed more people worldwide than all the battles had done.

For all that, a plan did exist. Sir Philip Neame, in October, 1918, had been ordered to quit his appointment as GSO 1 of 30th Division in order to become chief operational Staff Officer to No 2 Tank Group. Three such formations were to be formed, each of three Tank Brigades of four 60-tank battalions. The armoured force of 1919 would, had it come into being, have contained as many tanks as seven armoured divisions in the next war without counting the 10,000 tractors. As none of these formations ever existed one must regard them as the army of a dream. Twenty years later it became a nightmare.

Plan 1919 came off when tried, but by then it was Plan 1940 and was written in German. Even that, against French Generals of Foch’s kind, might have failed. It is a large question and there is no point in worrying it to death. One thing is certain. In the Kaiser’s War the Empire lost some three-quarters of a million of its best young men, killed outright or died of wounds. Had the pioneers not had the brains, the skill and the pertinacity to make their tanks and the hardihood to fight for them against entrenched prejudice that figure would have been far higher. The descendants of those infantrymen who came safe home might give them a thought every time the Two Minutes’ Silence comes round.

Thus the war terminated, and with it all remembrance of the Tank Corps’ services. It reckoned itself lucky to escape disbandment.