IT VERY NEARLY HAPPENED. In the moment of victory the tank did not lack for friends but after a pause for thought cautionary voices were raised. Sir Douglas Haig included in his Final Despatch a section quaintly headed ‘The Value of Mechanical Contrivances’ whose conclusions were both firm and reasoned. ‘Weapons of this character are incapable of effective independent action. They do not in themselves possess the power to obtain a decision. To place in them a reliance out of proportion to their real utility … would be a disservice to those who have the future of these new weapons most at heart.’ On 8 August, 19185 and the following days, Sir Douglas pointed out, ‘A scrutiny of the ammunition returns disclosed the fact that in no action of similar dimensions had the expenditure of ammunition been so great.’ Sir Henry Rawlinson made a similar point in his Foreword to The Story of The Fourth Army which he wrote in December, 1919. After giving tanks the praise they deserved he qualified it: ‘There is always a tendency on the part of a new service like tanks, aeroplanes, or even machine-guns when first employed in a general action to think that they can win the battle on their own.’ The ‘all-tank’ idea was officially disapproved. Tanks were a useful addition to the traditional arms but they were no substitute.

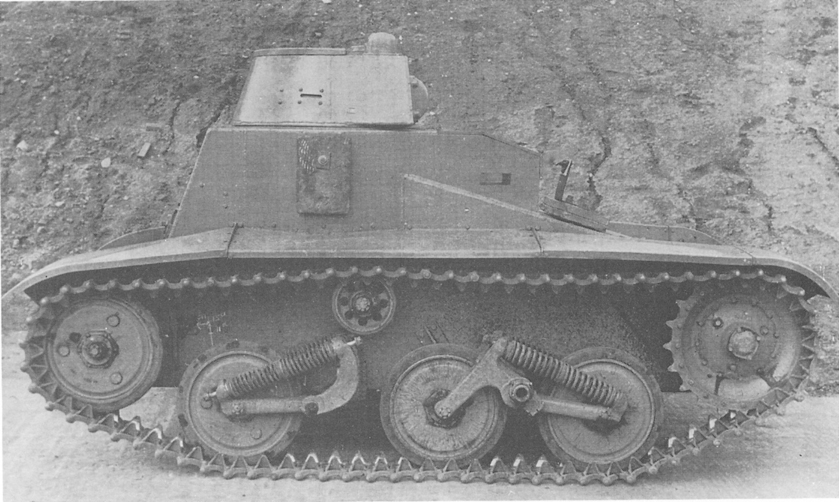

The Vickers Light Mk 4. A slightly later version of Mk. 2.

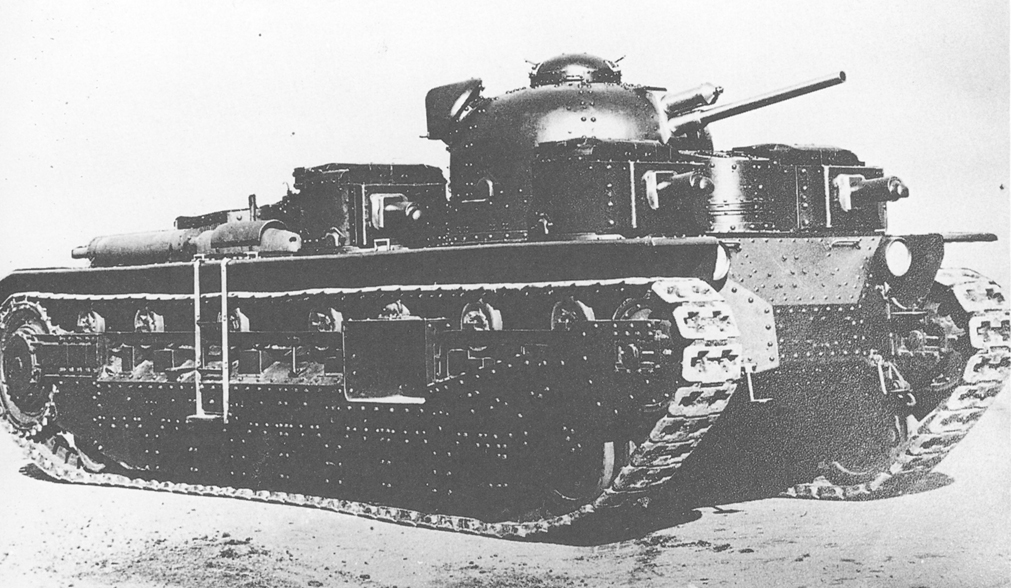

The Vickers Light Mk 2 Tank. Another between-wars machine.

There were many and various committees dealing with the future of all the armed services. This was the period when Punch joked about a new uniform for the RAF appearing every week and strange-sounding ranks like Reeve and Third Ardian were being seriously proposed. The Tank Corps was humbugged in much the same way. One suggestion that came quite near to being adopted was that it should be treated on a par with the African Colonial Forces and officered by people seconded for short tours of duty. Nobody knew quite what to do with an arm that was undeniably useful but with functions that could not be called merely defensive.

The war to end war had left the British Army stretched as never before. Quite apart from ordinary peacetime functions, it was faced with a campaign in Waziristan, something very much like a campaign at Archangel and Murmansk and the possibility of yet another in the near East where a new Turkey was manifestly not disarming in accordance with the Treaty, but was up to something. There were formations scattered about from Tiflis to Constantinople and smaller ones in Persia and Mesopotamia; Ireland demanded troops; an Army of Occupation stood on the Rhine; the Palestine Mandate demanded its share in addition to the forces in Egypt. All these contingents had to be found from an Army that was melting away like a snowman in the sun. Conscription did not end until the Spring of 1920 but drafts seemed to become smaller and smaller.

The old Regulars were nearly all gone, dead, maimed or time-expired. The Territorials, their numbers saved only by the return of the three Divisions sent to India and thus unscathed, reverted to the condition known as disembodied. The remainder, Kitchener men, Derby men and conscripts, were clamouring to be released before all the civilian jobs had gone. New Regulars were enlisted as quickly as possible but they were few in numbers and very young. The Tank Corps melted faster than most, for it was made up almost in its entirety from non-Regulars. Mitchell put the professional soldiers at no more than two per cent of the total; most of these were the senior officers who, fortunately, were senior enough to compel attention when they spoke.

The pioneers dispersed in much the same fashion. Crompton returned to electrical engineering and in 1926 won the coveted Faraday Medal. The Admiralty claimed back d’Eyncourt, though he remained a member of the War Office Tank Committee. Swinton, who had been on a long lecture tour in the United States, left the Army and became Controller of Information for civil flying at the Air Ministry. Stern rejoined the higher reaches of money-lending, becoming a Director of the Midland Bank as well as of various overseas finance houses. Tritton, having beaten ploughshares into swords, resigned himself to beating them back again. Wilson likewise continued with his own particular mystery and founded the company called Self Changing Gears Ltd. Ricardo also went back to his beloved petrol engines and made a considerable name for himself in the world of mechanical engineering.

Not much remained of the Tank Corps once the Victory Parades were over and a number of surplus Mk IVs had been posted in market squares as reminders to a new generation of what their crews had once achieved. Of the rest of the machines, most were dumped around Bovington to await either purchasers or the scrap-merchant. Their military value now was about equal to that of HMS Victory. Williams-Ellis indeed suggested that the best thing we could do would be to sell all the Mk Vs and Whippets to any potential enemy we might have. A few Whippets went to Denikin’s White Russian Army and fell into Bolshevik hands for nothing. Some remaining armoured cars, the last ones made by the American Peerless Company to Austin’s specification, roamed the muddy roads of Ireland to provide targets for the IRA. A few Mediums were sent to India in order to ascertain whether they would be of any use on the North-West Frontier. They were not. The Tank Corps was reduced to four battalions, one for each Home Command from which in the laughable possibility of another European War the four Divisions would presumably be raised again.

The general belief was that the tank had been created for one purpose only, to break the Hindenburg Line. Having done that, its occupation was gone. There was no case made out for persevering with the long battering-rams of ‘Mother’s’ brood but one might exist for something lighter and faster that could be employed in open warfare. Even this was far from certain. The Army, bidden to get rid of everything not absolutely essential, obeyed. The mighty Machine Gun Corps was disbanded, such of its guns as were not sold being handed over to the Support Companies of infantry battalions. Practically everything relating to chemical warfare was hurriedly scrapped; all that was allowed to remain was the unarguably defensive respirator; to test it tear-gas chambers were permitted. These were not unpopular with recruits for they were held to be the best cure for the common cold. Thanks only to Mr Churchill the heavy guns were laid up in mineral jelly on the off chance that they might be needed some day. They were.

The greater part of the equipment of the Royal Air Force was sold off at thieves’ prices. The entirety, aircraft, engines, spares and everything else, fetched £5,700,000.

Over everything hung the shadow of the American Debt. Some of Mr Churchill’s writings suggest that he did not find President Coolidge’s ‘They hired the money, didn’t they?’ entirely worthy of a Power that had got off so lightly. When he had taken on the job of furnishing the AEF with all the heavy artillery it demanded there had been a simple word-of-mouth agreement. We would make no profit; they would underwrite any loss. Times had changed. Though the reasons were not the same as in Mr Asquith’s day every half-penny spent on the armed services was grudgingly doled out as if it had been the last one in the Treasury.

Bovington remained, a shadow of its former self like some little Norman church huddled in a corner of an abandoned Legionary fortress. Throughout 1919 and 1920 it clung to such tanks as remained serviceable, constantly patching and mending. Sir Hugh Elles stayed on as Commandant until 1923 when he was given an infantry brigade and moved upwards along the usual lines. An uneasy feeling was growing up among tank men that he was no longer to be counted on as their champion. Like many other people he was veering towards the view that anti-tank weapons were now so strong that no armoured vehicle could stand against them. Not that this was of more than academic interest, for the Ten-Year Rule laid it down firmly that no war would happen during that time. All the peripheral tracked weapons, the gun-carrying tank, the mine-roller, the folding bridge, the wireless tank, the crane-carrying salvage tank and the rest, withered and died. Mr Churchill, in The World Crisis, asserts that the neglect of the torpedo-carrying seaplane was ‘one of the great crimes of the war’. Language rather strong, perhaps, but neglect of the self-propelled gun was every bit as bad. When the bell sounded for Round Two all these lost arts had to be rediscovered.

Two men remained in the Service to speak up for Mechanical Warfare. Fuller and Martel alone kept alive some interest in the subject during these critical years. Even they could not have achieved much but for a stroke of good fortune. From January, 1919, until February, 1921, the Secretary of State for War and Air was Mr Churchill, probably the only Minister who had not deluded himself about the possibility of the Army having again to fight a serious war. ‘Kill the Bolshie; kiss the Hun’ was his admirably succinct description of the policies needed. Nor did he require any homily about tanks and the need for them. Suggestions that new ones were essential got from him a sympathetic hearing.

There were no tank manufacturers left. Once production had ceased, companies like Metropolitan, Marshalls, Fosters and Fowlers wasted no time over returning to their ordinary business. The only possible candidate for producing new machines was the firm of Vickers. Though long established in the armament business Vickers had never made a tank. They were, however, willing to add tank production to their other interests, but only upon terms. It was not seemly for Vickers merely to build to other men’s designs. They would recruit their own experts; this they did, eventually setting up a design office in Sheffield. When the Master-General of the Ordnance asked for a new design they produced it themselves. Neither Fuller, at the War Office, nor Johnson, who had planned the Medium D, was consulted.

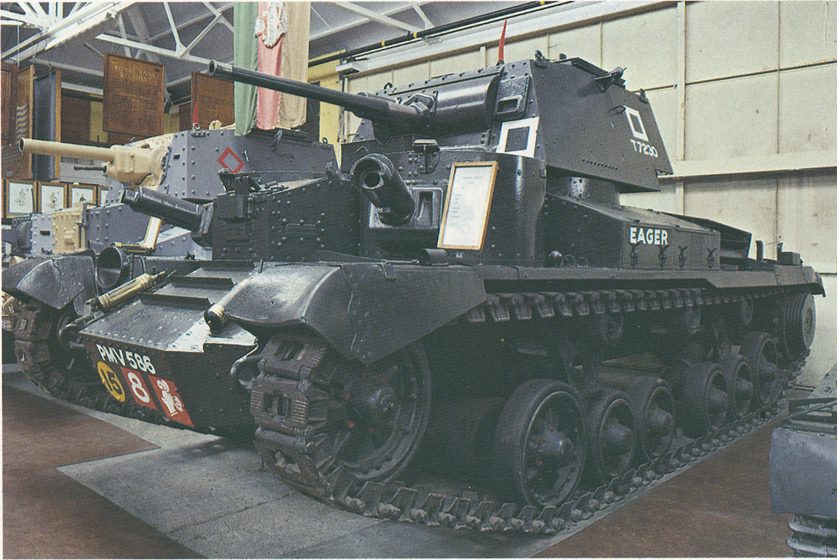

The Vickers Medium Tank Mk 1A.

In 1921 the first Vickers Medium Tank made its debut. It was mechanically a good machine, built with the loving care that men had once put into the building of cathedrals. Rough wartime finish would not do for Vickers. Their tanks were built to last; which was just as well as this model and its immediate successor would have to do duty for many years to come. The armour was still very thin. More weight spelt more fuel consumption. The Mk 1 weighed 12 tons, much the same as a Whippet but there the comparison ends. An Armstrong Siddeley engine of 90 hp gave it a top speed of 18 mph and a cruising range of more than a hundred miles. The track had been completely redesigned, for the Tritton-Wilson, though a splendid performer on slow machines, was not up to these much greater speeds. Like the Renault FT 17, it carried a revolving turret in which was mounted the same Vickers 3-pdr gun that had been rejected in 1916 as being too small. The crew numbered five and the tank could cross a trench six feet wide. This was considered quite enough since trench-crossing was no longer of first importance. Major-General Sir Louis Jackson, lately Director of Trench Warfare, had made this quite clear in the course of an RUSI lecture in November, 1919. ‘The circumstances which called (the tank) into existence were exceptional and are not likely to recur. If they do, they can be dealt with by other means.’

Vickers held a monopoly in tank production for the better part of twenty years. It was not of the Company’s seeking. Nobody else wanted work in which chopping and changing of specifications by people who only half-understood what they were doing went on far too much. The taxpayer did not suffer. During the 1920s and early 30s Vickers, without any help – if that be the right word – from the War Office produced a notable range of light tanks as part of their ordinary commercial activities. For home consumption they built between 1923 and 1928 160 of their Mediums but these were only part of the Company’s output. Foreign Governments subsidised research and development by buying the machines the War Office did not want. The 6-tonner of 1933, for example, was sold all over the world, even to customers as unlikely as Bolivia and Siam. Soviet Russia and Finland were both purchasers, the Russians basing their own light tanks upon Vickers’ models. The Finns were less fortunate. The last half-dozen they ordered in 1939 had not been handed over when the Russian invasion came; they ended up as training machines for the British Army. It might have been better to have disbanded all the inexpert War Office Committees and to have turned the whole business over to the professionals. With Generals of the quality of Sir Herbert Lawrence and Sir Noel Birch on the Board they would not have lacked for competent advisers.

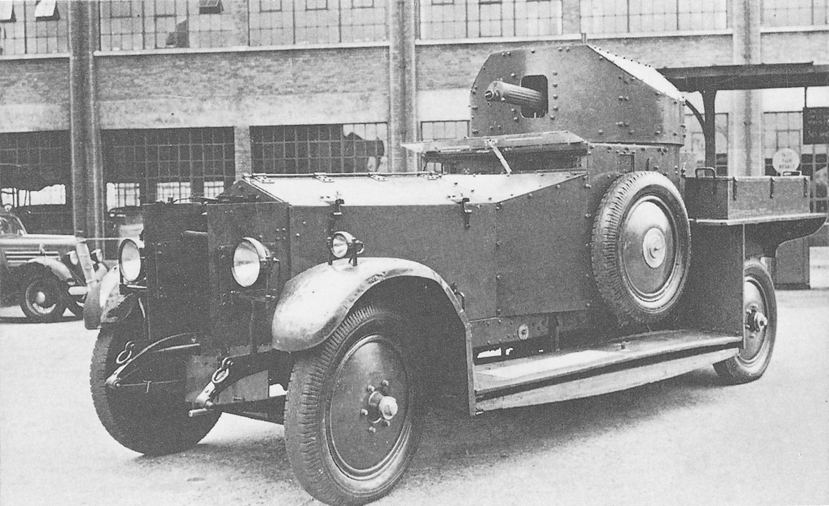

Armoured cars were treated differently. The solid-tyred, twin-dustbinned models looked absurdly out of place on English peacetime roads. They were soon phased out in favour of the far more chic Rolls-Royce, Lawrence’s ‘Blue Mist’ with a turret; even with this piece of camouflage they could not help looking the aristocrats they were. The Peerlesses, being fairly new and having cost a lot of money, were handed over to the Territorial Army, itself re-born in 1921.

The fingers in the pie from which a new tank might be pulled out were many. First came the Master-General of the Ordnance himself; his department was divided up into four Directorates, the one with responsibility for tank production and many other things being the Director of Mechanization. His office was divided into three parts, the first dealing with engineer and signal stores, the second with all kinds of tracked vehicles and the third with second echelon, non-fighting, motor transport. Superimposed upon the Director was an advisory body called the Mechanization Board, mostly officers serving at the War Office but thickened up with civilian experts. To assist in their conjoint efforts was the Tank Testing Section – later known by other names – at Farnborough. Once a new machine was over all these obstacles, it was submitted to the Chief Inspector of Armaments at Woolwich where every component part was supposed to be keenly scrutinized. For the Medium tank this meant the examination of some 2,500 parts set out in the inventory contained in a thick book. It is hardly remarkable that years might elapse between design and prototype; delays were often prolonged by constant tinkering with plans which halted production and the insistence on a high standard of finish more suitable to the Motor Show. It was rare indeed for any member of any Board or Committee to be drawn from the Tank Corps. All the same, in the late 1920s the arrangement seems to have worked. British tanks were still the best in the world and there was no call for any ‘Boot and Saddle’ over their production.

Unfortunately the Medium was expensive. Almost at the same moment as it appeared Herbert Austin surprised and delighted the world with his baby car and the cry inevitably went up ‘Why build a tank comparable with a Daimler when, for same money, you can have half a dozen Austin Seven equivalents?’ To this there was no answer. Martel, himself a qualified mechanical enginer, decided to have a try on his own. His tiny machine was trooped around the Staff College and gave everybody a lot of fun. It was not, however, anything to be taken seriously.

When Sir Edmund Ironside was appointed CIGS in September, 1939, to his own indignation as he had been expecting the fighting command, he had much to say about the then tank situation. One remark is interesting. Our tanks, he said, were unfitted for war in Europe. He may very well have been right. The League of Nations in its starry-eyed phase, along with the various pacts, had reduced the British Army to an armed colonial police force. Its enemies thenceforth would not be Hohenzollerns and Hindenburgs but the likes of the Akhound of Swat, the Fakir of Ipi and the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. Against such as these the smallest and cheapest tank would do. If, indeed, any tank were needed at all.

Then, in 1924, came the first Labour Government and the voice of the conscientious objector was heard in the Cabinet. The word of power was ‘disarmament’; strictly defensive weapons, such as the ageing guns sunk in concrete and overlooking Dover Harbour, were legitimate. The same guns taken out and mounted on carriages were offensive and unlawful. Good socialists can tolerate armies provided that they are not efficient. Everything of an offensive description must go. Disbandment of a Corps that could by no stretch of Socialist imagining be called defensive was once again on the cards. Fortunately the Administration did not live long enough to attend to it.

The Locarno Pact of 1925 declared war to be illegal. The War Office, with all its faults, did not subscribe to the view that its duties were now limited to calling an international policeman when something blazed up. Orders were placed with Vickers for a new tank, not merely an improved Medium – though the Medium Mk II did appear in the following year – but something that would make possible the mechanized war of Fuller’s dreams. It was to be big enough and powerful enough to take on fortified positions with a decent chance of success, but it was to be more than an up-dated Mk VIII. The proposed machine would also have to be fast enough and of sufficient endurance to work in large bodies of its own, no longer tied to the pace of heavily burdened foot soldiers. It must be capable both of fighting Cambrais and of improving upon Rolling’s armoured car raids on enemy headquarters.

Sir George Buckham, head of the design team, had been with Vickers since 1895 and by now had a seat on the Board. Under his guidance the designers and engineers came up with a very fine tank indeed. Officially it was styled the AI, first of a long line of ‘A’s, but the name used for it by everybody was the Independent. AI weighed in at 32 tons, a monster for its day, and could carry its 47 mm gun and four machine guns in their separate turrets at a steady 20 mph. Its armour was no better than that of a Mk V but in every other respect Independent was years ahead of its time. Buckham’s men showed it off at the Imperial Conference and received polite applause. Here was the machine constructed as its name implied for warfare of a new kind. Squadrons of Independents would be able to do in reality all that the free range Medium Ds had accomplished in Fuller’s dream and more besides. A few hundred of them with their eight-man crews would be of more value than an old-style Army Corps. Neither the Army Council nor the Treasury saw it that way. Only the one specimen was made. You may see it sitting forlornly in the yard of the Tank Museum, a monument to the barnacled minds of elderly gentlemen. No price would have been too high for an updated Independent in the hot summer of 1940. It was fortunate that Soviet Russia, of all countries, discerned its merits and copied many of them into their highly successful KVI. Sir George’s work was not entirely wasted: Nazi Germany came to know all about the KVI.

Though Fuller went on and on about the tank versus tank battles that must abound in any future war – another of those blinding glimpses of the obvious that some military minds refuse to see – the policy reverted to the old one. As the best tank in the world had been wantonly thrown away the obvious next step was to settle for the worst. Not that there was anything wrong with the Vickers Light Tank; except, of course, that with no more than a machine-gun and with armour proof only against small arms fire any tank that carried a gun could kill it quickly. No tank in the later 1920s was even contemplated as the means of bringing down fire from anything heavier than rifle-calibre weapons, the only exception being the elderly 3-pdr. One cannot but suspect some members of the Royal Regiment of Artillery of bringing this about. Guns are sacred things, the equivalent of Colours. They must not be degraded by being put into the hands of non-gunners, not even very small guns.

There were many Gunner officers in positions of power and few of them trusted ‘Boney’ Fuller. He was indeed a strange figure, in some ways reminiscent of Robert Craufurd in the Peninsula. Both were capable of brilliant planning; Craufurd’s operations on the Coa and Fuller’s at Cambrai are examples. Against that, both were capable of what the Duke called ‘mad freaks’. Fuller, as he grew older, seemed to withdraw from reality into a Jules Verne world. His 1919 essay on ‘The Application Of Recent Developments In Mechanics And Other Scientific Knowledge To Preparation And Training For Future War On Land’ won him a medal; but it frightened many staid men off the tank idea. The devil they knew was at least a familiar devil. Had they known Fuller to be on corresponding terms with Aleister Crowley, alias The Beast 666, they would have been more frightened still.

The plans he had long ago matured for the perfect destruction of a hostile army had become common knowledge. To Fuller the number 3 possessed a mystic significance and all his calculations were based on that digit. The Rule of Three had worked at Cambrai and it would work even better at the Cambrais yet to come. Three semi-independent forces would be needed. First to go in would be the Disorganizing Force, Medium Ds or something better, whose charge it would be to pierce a hole, pour through it, and beat up all headquarters from Corps down to Divisions. It would not, if it could help it, smash up communications; these would be better left to wail out demoralizing messages to the troops in front of them about what was happening in rear. Then it would be the turn of the Breaking Force of heavier tanks and self-propelled guns to smash through a line that, with any luck, would have become disorganized. Lastly, behind the Breakers, would flood in the third wave of fast light tanks and their attendant mounted infantry in lorries to cut down the fleeing rabble. It sounded excellent sense, provided only that the enemy played fair and sprang no surprises of his own. When the German Panzer divisions put it into operation it proved needlessly complicated. The French Army disorganized itself.

In a perfect military world where men of high intelligence were available in great numbers and money was no object Fuller might have achieved great things. In a very imperfect one, where infantry depots were glad to scrape up any recruits they could find and Adjutants went prematurely grey in having their drafts ready for the Indian trooping season, his imaginings were rich in academic interest but barren of much practical importance. Fuller’s influence upon the Army as a whole was not profound, at any rate after 1927.

The cavalry for some years to come went on its elegant way, unburdened by worse things than the Aldershot Tattoo and the King’s Birthday Parades. They had nothing further to learn, for the whole business of horse-soldiering had been mastered centuries ago and it was only a matter of passing it on. Infantry battalions still took a proper pride in their standard of march discipline.

The tanks, though little seen by the public, worked away at their trade. Baker-Carr’s old friend Colonel George Lindsay assumed command at Bovington; no man was better equipped for the task. Fuller’s days with tanks were drawing in by the mid-twenties but another star was rising in the East. Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart came from the Indian Sappers and Miners, with whom he had experienced some of the pre-tank battles on the western front in 1915. When the Indian Corps had been withdrawn Hobart found himself in Mesopotamia where he had as rough a war as most men. If Fuller bore some resemblance to Craufurd, Hobart is reminiscent of Mangin, for he was a fierce man and suffered no fool near him. Fool, in Hobart’s vocabulary, meant any man who disagreed with his ideas. He himself wrote his views, tersely enough, on military matters in a confidential report. ‘This officer plays cricket. Need I say more?’ Though he had seen nothing of tanks in battle Hobart was determined to learn, for he had a clear grasp of what future war would be like. In 1924 he transferred to the newly christened Royal Tank Corps, but for serious business he had a long wait ahead of him. His first three years were passed still in India where only a few armoured car companies represented the Corps, but he entered at once into a spirited correspondence with Lindsay at Bovington. Each struck sparks off the other. By the time he arrived at the same place in 1927 Hobart was well marinated in tank doctrine.

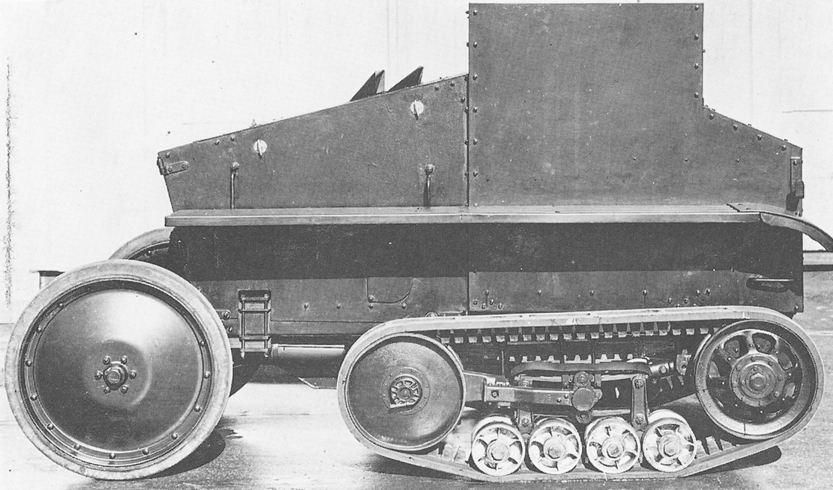

The other protagonist of the future, Colonel Martel, was still busy inventing things. In 1925 he had met Sir John Carden, 33 years old and a 7th Baronet, who was joint proprietor with a Mr Loyd of a small London garage. Carden possessed something like a genius for design and the two men worked happily together. Out of the garage came some very small machines of the two – and even one-man kind. The most successful was a simple tracked affair which without many changes was to become the Bren carrier which every Second War soldier knew. Some of the other designs were less successful. Mitchell tells of Mattel’s plan for a four-tracked tank, ‘long and low and looking like a dachshund’. It never got further than the drawing-board. He also wrote of a tank equipped with a hinged pole by means of which it could jump ditches. Again, it was never more than an idea. The French stuck to Louis Renault’s little machine which seemed good for a long time to come. The main thrust of Martel’s thinking was towards the very small and cheap, to be turned out in great numbers. His ‘tankette’ – a name mercifully forgotten – was made from ordinary commercial parts and cost, at £500, about the same as the Rover saloon car. The idea was that swarms of these machines should move ahead of the Army, as Napoleon’s Tirailleurs had done, until they struck opposition. If it was not too heavy they would press on and prepare the way for the bigger machines following behind; if it proved too much for them they would halt and convert themselves into minuscule pill-boxes. In all this there was an air of strident unreality. In practice the ‘tankettes’ served a small purpose by bringing instruction in driving and maintenance to men who otherwise would have had none. Stern, who had always had a fancy for the heavy tank, was scornful. These toys were not for fighting. Martel might have privately agreed with him, but he was in much the same case as Elles before Third Ypres. Better to have something, however feeble, that boasted an engine and a pair of tracks than nothing at all. And nothing at all seemed the alternative.

Money was not the only limiting factor. Since 1919 the Army had gone back to proper soldiering as understood before the Kaiser’s War. Sir Philip Neame tells of how ‘I served at Aldershot in 1924 under a Major-General who took me to task for introducing tanks into a military exercise, as he said that he was not going to have his infantry frightened by the idea of any … tanks!’ Exactly what had once been said of machine-guns.

Fuller had one last blow to strike for his Corps. In 1926 Sir George Milne had been appointed CIGS with Fuller as his Military Assistant. Milne, who had won in Macedonia the rare distinction of being known to his troops as ‘Uncle George’, was a Gunner but prepared to listen to a man from the younger arm. The upshot of it was that before the summer of 1926 was out Milne, against much opposition within the Army Council, had persuaded Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, Secretary for War, to allow him to form an experimental armoured force and try it out on Salisbury Plain. It was not only Fuller who had worked on the CIGS. Captain Liddell Hart had dined with him at the Norfolk Arms, Arundel, and had reinforced the argument.

It was left to Fuller to work out the details and he came up with a plan. It had fairly modest beginnings: a tank battalion, a company of armoured cars, a lorry-borne infantry battalion and machine-gun battalion along with a battery of self-propelled guns and another drawn by the tracked machines known as ‘dragons’. The self-propelled gun would be the ‘Birch’, of which more later. There was much tinkering with the Experimental Force but for the time being it came to nothing. The Treasury refused to find the money. In the year of the General Strike it is hard to blame them. The cash was found in the year following.

The summer of 1927 was distinguished for almost incessant rain. It was remarkable also for the first appearance since 1918 of an armoured, mechanized force at work. Fuller, through his own fault, did not command it. Instead he forced a silly quarrel upon the CIGS because he was not allowed to escape the humdrum duty of commanding an infantry brigade as well as having the fun of directing the great exercise. The quarrel ended with Fuller being translated to work where he had nothing further to do with tanks. Command of the Experimental Brigade passed to Colonel Collins who neither had nor claimed to have experience of the necessary kind.

Before the exercise began the Army, to show how modern it was becoming, put on an exhibition of its new machines for the benefit of a party of Colonial Governors. All the latest cross-country vehicles were put through their paces. Some, like Morris’ 6-wheeler 30 cwt truck, were excellent. Others were downright freakish, such as the car with a detachable undercarriage which could suit itself to either wheels or tracks as the situation demanded. A half-tracked Morris Cowley, capable of perhaps 60 mph, pulled a hickory-wheeled 18-pdr gun capable of about 5. The Governor of Nigeria, Sir Graeme Thompson, said politely that it would have a great effect upon the future of our Colonies. This was not borne out by subsequent events.