THE GREAT EXERCISE OF 1927 ought to have had more effect upon the future of mechanized warfare than it did, for it was pretty much of a success. The correspondent of the Illustrated London News wrote enthusiastically about it. The object of it all, he said, was to find out whether it was more advantageous to advance with machine-gunners carried in tanks or to send the tanks off first and let the guns follow in the old style. Every Vickers Medium and every tankette available was used, along with every horsed unit and every horse-drawn gun. In the battle of 24 August the ‘Blue’ force of tanks drove the ‘Red’ infantry off a hill. On the following day a cavalry brigade mixed it with the Experimental Force, with surprising results. The Times man reported that ‘I was in time to see an interesting fight between the Lancers and armoured cars in a large field. The mix-up between horsemen and machines was indescribable. Owing to the good placing of the anti-tank machine-guns of the cavalry the umpires gave the decision in their favour.’ The ‘anti-tank machine guns’ were, of course, still the pre-1914 Hotchkisses, which might as well have been red flags. The Illustrated London News carried a picture of horsemen scrambling up a bank, apparently to avoid being run over, with the caption ‘Cavalry crossing a road on which are seen two captured tanks.’ How the cavalry captured them is unclear, but umpires can work miracles. Another picture shows clusters of horses slowly dragging artillery pieces across a skyline. ‘A picturesque view of a battery advancing during a battle.’ Nevertheless, on the same authority, ‘it was ruled that tanks are the decisive arm and infantry are in support’. The RAF amused itself by flying low over the performance in order, perhaps, to frighten the horses, and a gesture was made towards the use of smoke. Tank Corps officers marked the transitional nature of it all by wearing berets and spurs.

On the serious side, the exercise gave both the ‘all tank’ men and the ‘cooperation between arms’ men a lot to think about. It was, none the less, a mere beating of the air until some high authority should pluck up its courage and remove horses from the battlefield where they no longer belonged.

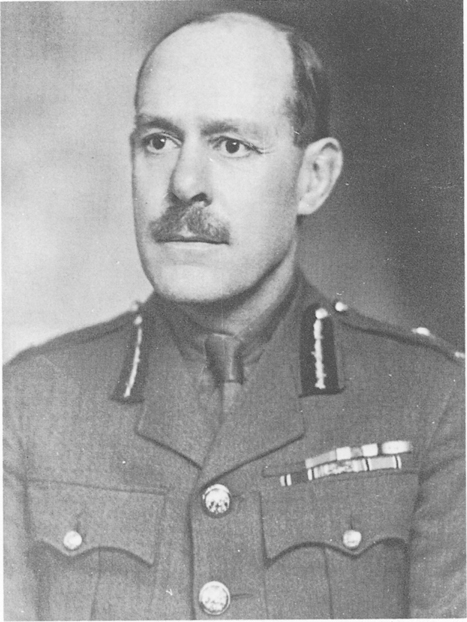

Fuller, you will remember, had spoken of self-propelled guns being part of the Experimental Force. No such weapon had existed since Wilson’s tank carrying a 60-pdr had been degraded to coolie labour. General Sir Noel Birch – ‘Curly’ to his peers – had been Sir Douglas Haig’s chief artillery adviser; with the possible exception of his German opposite number, Bruchmuller, he knew more about the business of gunnery than any other man. The ‘Birch’ gun – an 18-pdr mounted on a cut-down Vickers Medium chassis – had been constructed to his design; no fault could be found with it nor did any officer of stature speak other than in terms of praise. General Birch could never have been called an enemy of the horse, for in his spare time he had written books on equitation and he was a well-known coaching whip. In spite of all these things he was unable to persuade the Royal Artillery to take up his new weapon. There was no reasoned argument against it; merely that if such a thing were taken on Gunners would have to dress themselves in dungarees, cover themselves in grease and develop new smells. Not only would the ‘hairies’ who pulled the guns have to go but in all probability their hunters and polo ponies also. A cavalry regiment, they knew, was listed to become rude mechanicals but not the artillery. ‘Curly’ was due to leave the Army before long, and authority forgets a dying king. The Birch gun made its last appearance in 1928. It would have been beyond price in 1940.

The anti-mechanicals movement was not confined to comparatively junior officers. Sir Douglas Haig had won great battles with tanks and had given them enthusiastic praise. Retirement seemed to have switched him to General Jackson’s opinion: tanks had been created for a specific purpose that no longer existed. In his counter-blast to Liddell Hart’s Paris, or The Future of War he set out his thoughts on paper; ‘I believe that the value of the horse and the opportunity for the horse in the future are likely to be as great as ever … I am all for using aeroplanes and tanks, but they are only accessories to the man and the horse, and I feel sure that as time goes on you will find just as much use for the horse – the well-bred horse – as you have ever done in the past.’ The year was 1925. General Birch’s reputation stood very high but none equalled that of the old C-in-C. The Horse Artillery could thus appeal to Caesar with confidence. A mere five months after the 1928 exercise Sir Douglas died. Like Caesar, the small piece of evil that he had done by this lived after him; the good was interred in Dryburgh Abbey.

Horse-magic lived on far too long. With the Birch gun sunk without trace the artillery moved a step backwards. Their pieces were, undoubtedly, now pulled by mechanical vehicles but they still pointed in the wrong direction, as guns had done from the very beginning, and needed to be unshipped and hauled round before they could perform their office. One regiment, however, succumbed. In 1927 the nth Hussars, the famous Cherry Pickers, acquired a new name. On being deprived of horses they became known as the Sparrow Starvers. As a douceur they were put not into tanks but into 1920 vintage Rolls-Royce armoured cars. The nth still retained a high degree of tone. The 4th Hussars, personified by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, were not jealous.

Another Salisbury Plain exercise took place in 1928. An armoured car battalion, a battalion of Mediums, a field brigade of artillery and a motorised infantry battalion took on the 3rd Division. With leaders like Martel, Pile and Hobart to do the planning and execution, it comes as no surprise to learn that the Experimental Brigade cut rings round their opponents, who moved at the pace of Marlborough.

The Division, apart from the presence of many new faces, was still the Division of 1918. It possessed no weapon that it had not had then and was helpless when attacked suddenly from an unexpected quarter. The prophets of the future war naturally gained much kudos. The oddest thing about it all is that none of them seemed in the least interested in anti-tank weapons. When these eventually came, many years later, they were no more than slightly improved versions of the German equipment of 1918, rifles or small guns that threw a solid slug of metal at great velocity. A modest prize put up in 1928 would surely have produced something that could have changed the entire state of affairs. When matters became desperate the Sticky Bomb, the PIAT, the Blacker Bombard and the Bazooka seemed to spring up overnight. At a time when the RAF High Speed Flight was winning the Schneider Trophy with regularity it can hardly have been beyond the skill of scientists to have produced some weapon of this kind, however crude, by whose agency a couple of infantrymen might stand a chance of knocking out the thin-skinned armoured vehicles of the day. Instead, infantry battalions on training exercises were kitted out with a series of coloured flags that could represent anything from a Soyer stove to a battleship.

In a way the unsurprising success of tanks over marching infantry was as much to be regretted as the ‘Dash To Kimberley’. The parts of the army moved by petrol and by animal-power began to draw away from each other. Tanks pursued their own interests while the remainder – and by far the greater part – of the Army continued in the old way. Drafts were made up for India, Egypt and Palestine and training was as unrealistic as ever. In January, 1927, a Division had been hurried to Shanghai where a little-known Chinese war lord named Chiang Kai-shek was on the rampage. No tanks went with it but SS Karmala carried a dozen of the Rolls-Royces belonging to No 5 Coy, RTC in her hold. Armoured cars had been useful during the regular Hindu-Muslim ‘cow-rows’ and would no doubt come in handy here. There was no knowing where the next brush fire would break out but wherever it was it would be a job for the under-strength, under-trained second battalions from Catterick or Tidworth. Tanks and their accomplices were, to the War Office, an eccentricity far removed from the mainstream of proper soldiering.

In 1929 France took a decision which was to alter much of the thinking about mechanized warfare. It was the year in which Foch died, and his assertion that there was no more than a twenty-year armistice, half of it gone, had not been forgotten. Stories had been current for a long time about how von Seeckt was quietly building up a new and more formidable German Army. A deal had been done with Stalin, so the rumour ran, and Germany was making and training with tanks somewhere in Russia. No tank, however, could overcome the combined effects of great ditches, mines and anti-tank guns. The French Army had no intention of being caught as it had been caught in August, 1914; no more bands playing ‘La Marseillaise’ and columns of men marching up to the expectant guns. Next time the Germans could try it. France had suffered enough for one century, as a visit to Verdun will still testify. Every village had its long bronze scroll naming its dead, scrolls still unweathered by rain or time. Ex-Sergeant André Maginot was one of ‘Ceux de Verdun’ where he had lost a leg. With him at the War Ministry the digging began.

It is now considered a mark of sophistication to sneer at the Maginot Line. Nobody sneered when excavators started work on the elaborate tunnel system. The Line was regarded with awe, even though it was imperfectly understood in this country. On the outbreak of war in 1939 one of the most popular maps on sale was the ‘All In One’ No 5, put out by the Geographer’s Map Company of London. It showed a comfortably thick black line running from a point in front of Metz to the sea by Dunkirk. Few people queried it; possibly because the Chamber of Deputies had resolved in 1937 to make the needed extension. The fact that no sod had been turned was not advertised.

It was not only the beginnings of the Line that marked out 1929 from other years. America had been growing fat. Strube’s Daily Express cartoon for 19 March, 1927, pictured two tramps on a park bench looking across water at Uncle Sam counting masses of notes in a skyscraper office labelled ‘US Treasury; £120,000,000 Budget Surplus’. One tramp, Strube’s Little Man, remarks to the other, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, ‘I say, Winston, aren’t you glad you haven’t got to sit up all night counting money like that poor fellow over there?’ The money was all borrowed and Nemesis duly caught up with Hubris. When New York caught its cold the droplets took some time to cross the Atlantic but the warning was there. In the eye of the storm that was about to hit London there was a moment of peace. The first Vickers Light tanks of just over four tons and carrying two-men crews put in an appearance in 1931 and for the next few years they were to be the mainstay of the Corps. The tank addicts thought themselves lucky to have even that, for current thinking was on other lines. With M Maginot’s works nearly complete what possible need could we have of an Armoured Division? Those in positions of authority seemed to have lost sight of one plain fact. The British Army throughout the nineteenth century had won its big battles from Bussaco to Omdurman by way of Waterloo by adhering to the Duke’s philosophy. Organize yourself with as much fire-power as possible, encourage your enemy to attack and after you have decimated him march out and finish off the business. The Maginot Line ought to do the first part but only a force of powerful tanks could do the second. This axiom was not understood by many politicians nor, as time would show, by all Generals. When suggestions were put about that the troops in the Line might be starved of supplies by aircraft cutting off the railways on which they depended, or that the glacis might be fogged by smoke under whose cover obstacles might be circumvented, they were brushed off. Men who said such things were ‘croakers’. Few, if any, said it twice.

The cold drove the Army into a kind of permafrost. When Lord Gort took over 4th Division its strongest battalion could parade 350 men; the weakest mustered 185 all ranks. Drill movements were carried out by two men with a rope extended between them, pretending rather pathetically to be a rifle company. Depots gladly took in anything that was recognisably human, male and over five feet two. False teeth were no bar. It speaks volumes for the quality of the between-wars NCOs and those under-appreciated men the Army Schoolmasters that the soldier who emerged at the end of six months was a different being. There were just enough of them to keep the units in India, Egypt and Palestine up to Peace Establishment. The Army at home was not even the Second Fifteen; it was the Colts, supported by the veterans. In 1931 even the miserable pay allowed by the Warrant was cut by 10%. This was bad enough from the point of view of recruiters; it was far worse for officers. No subaltern could be seriously expected to live like a gentleman on a ploughboy’s wages. It was generally reckoned that even the cheapest foot regiment demanded a private income of £200 from its aspirants; most required more like £400. The Tank Corps suffered along with the rest.

In spite of everything that had happened during the Kaiser’s War the Army was still class-conscious. Sir Douglas had told in his Final Despatch of how ‘A Mess Sergeant, a railway signalman, a coal miner, a market gardener, a Quartermaster Serjeant and many private soldiers have risen to command battalions’. They would never do so again. The Army Classes of the Public Schools were almost the only source of supply and competition from the RAF College at Cranwell was very stiff. As late as 1945 General Martel (late of Wellington) was writing that ‘the secondary school boy is handicapped. He has led a sheltered life. He usually lives at home and runs to his mother if he is in difficulties. The stern test of fending for himself which the public school boy has had to face is denied him.’ Even when the ‘Y’ Cadetship scheme came in there was little chance of a Grammar School boy joining the commissioned ranks. The intake of new Second Lieutenants began to show signs of drying up.

In the senior ranks, however, the Royal Tank Corps was fortunate. Apart from Martel, the founder-member, new names were coming forward. Lindsay, Broad, Pile and Hobart, all Lieutenant-Colonels, stood ahead of the world in armoured warfare lore. None had spent any part of his war service with tanks but by 1931 they had, with all a convert’s zeal, thoroughly mastered the subject. Charles Broad, an ‘all-armoured’ man, wrote the first training manual, commonly called the ‘Purple Primer’. He did his best to interest the RAF in the work of army – particularly mechanized army – co-operation but was given no encouragement. He therefore addressed himself to working out drills for armour alone. The general belief in 1931 was that wireless communication between vehicles on the move was not possible. By hard work and experiment Broad proved the experts wrong. It was imperfect, but it could be done. Once the technique was mastered tank commanders would not be left without orders, wandering aimlessly around in search of something useful to do. Under wireless control groups of machines could act together and show the power of the new machines. As Murat’s great voice had once rung from wing to wing of his charging squadrons so could Broad’s quieter tones direct his ironclads to move as one at speeds greater than any cavalry gallop.

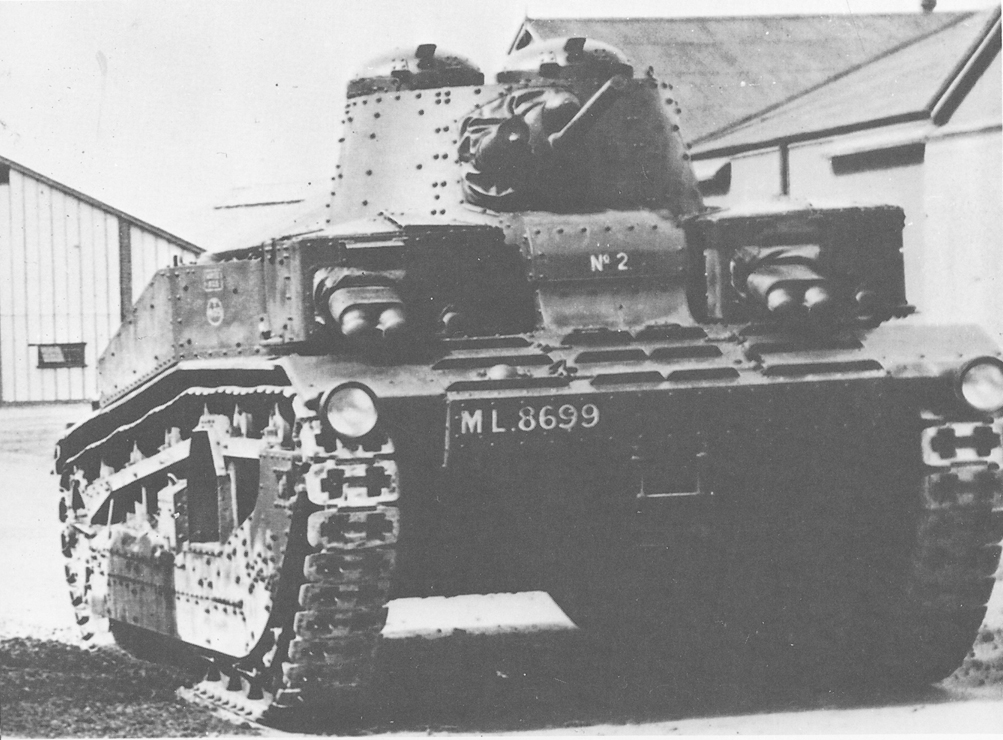

Before the Wall Street crash, orders had gone to Vickers for a new Medium tank to replace the ageing machines still in service. The Company came up with something rather good. The Vickers 16-tonner was designed on much the same lines as the Mk II Medium but it was bigger and faster. It was also, at £16,000, much dearer. As soon as three pilot models (the last with a new Wilson gear box) had been sent out for testing the order was cancelled and only three went into service. A request went out from the MGO’s office for something just as good but much cheaper. There was considerable argument about what it ought to be; so much that it disappeared altogether. The 16-tonners were the star turns of the 1931 exercise but never went into general issue. Vickers, who had bought out Carden’s patents in 1928, went to work on small carriers and light tanks instead. For the 1931 exercises there were about 230 machines in all. Fifty new light tanks, about eighty machine-gun carriers of various kinds and about 130 elderly Mediums. Of necessity they were mixed together even down to Company level. The exercise this time lasted a fortnight. German observers watched it with interest.

Twenty years earlier ‘Jacky’ Fisher had written in praise of Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson. ‘Three big fleets that had never seen each other came from three different quarters to meet him off Cape St Vincent. When each was many hundred miles away he ordered them by “wireless” exactly what to do, and that huge phalanx met together at the prescribed second of time … and dropped their anchors with one splash. Are we going to look at his like again?’ We were. The First Tank Brigade of 1931, though no great phalanx by later standards, might have given an answer to Fisher’s rhetorical question. It began its exercises in a thick Salisbury Plain fog and as the sun began to disperse it the watchers saw battalions of tanks, one of them Hobart’s, drilling like Guardsmen to Broad’s orders given by the same medium.

Another aspect would have won Fisher’s approval, for he had long since laid it down that ‘speed is armour’. The special idea was to demonstrate that speed had now come to the battlefield. Medium tanks pinned down the enemy to their front, while the fast, light machines peppered him from all manner of unexpected quarters. Broad, with his R/T and his corps of liaison officers, kept a complete grip on the attack. In the following year, under Brigadier Laird, the exercise was developed to show how an infantry column on the march could be surprised and cut up five miles away from the tanks’ assembly position. That done, Laird was warned by R/T of an imminent counter-attack by enemy armour. His change of dispositions to meet it took exactly ten minutes. The sheer expertise of the Corps won loud praise from all observers but the War Office was not won over. In 1933 the First Tank Brigade was disbanded and no exercise took place. The reasoning was simple enough. In a time of great financial stringency we should never have enough tanks to perform this sort of evolution in a real war. Since there could be no question of cutting down the meagre force of infantry we still possessed the only possible course was to limit tank activity to providing them with support in the old way. That war had become a possibility again, however remote, was proclaimed by the abandonment of the Ten Year Rule.

For this there were sound reasons. For some time past the newspapers had been recording the doings and saying of a Herr Hitler, as the name was then usually spelt. When, in January, 1933, he became Chancellor of Germany minds were concentrated wonderfully. Mussolini had always been regarded as a figure of fun and never taken seriously as a potential enemy. Four Divisions had gone to Italy after Caporetto and their fund of stories about the Italian Army were still good for a laugh. Hitler looked equally comical but the idea of a resurgent German Army was not funny at all. In 1934 the First Tank Brigade was put together again and command was given to the now Brigadier Hobart. He worked his crews mercilessly and the summer exercise of 1934 was reckoned to be the best and most imaginative yet staged. For the last time Britain demonstrated that in this new kind of warfare she had complete superiority over all possible competitors.

This could only remain true for so long as those competitors had no tanks of their own superior to the small Vickers and its much older brother. The limitations of the small tank were obvious and the Mediums were wearing out. Something better was needed to replace them and both Martel and Hobart rallied all the support they could find. There was little enough. Carden, now working for Vickers, drew out the plans for a cruiser tank – bigger than the light machines but not sufficiently protected for infantry work – and put it before them. Martel soon saw that the suspension was quite inadequate and bade him take it away and try again. This design was officially called the A9. There had been an A8, designed by Lord Nuffield, but it never got beyond the stage of drawings. Vickers’ design team went to work on the A9 and a heavier version to be called the A10 but progress was pitifully slow.

There had been changes at the top during the last couple of years. ‘Uncle George’ Milne finished his time as CIGS in 1932, saying wistfully as he departed that he was sure that tanks still had a future. His successor. General Sir Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd, had been Chief of General Staff to Fourth Army and had written its history. The new Master-General of the Ordnance was Sir Hugh Elles. From these two, reasonably enough, the RTC expected great things. They did not get them. Elles, long away from the tanks, had veered round to General Jackson’s opinion that they had been a ‘one-off’ thing, as gliders were to be in the war that lay ahead. The antidotes appeared now to be too strong for the kind of armour to which everybody was accustomed. Rumours were coming out of Germany of something called the Halger-Ultra bullet which was so powerful that it would make a colander out of any tank that might dare to show its face. It seems quite probable that there never was a Halger-Ultra bullet and that the story was deliberately put about with the purpose of discouraging those pressing for better tanks. After a time Elles changed course again but not to anything like full circle. He conceded that there might be a place for the very heavily-armoured infantry support tank – the ‘I’ tank for short – and he personally attended to the design of a machine to meet his own specifications. It was called the AII.

The French did better. Not all their Generals were hypnotized by the Line and France has never lacked for skilled mechanical engineers. While some of them were designing thoroughly bad aircraft, others were working on very good tanks. Three new models came out of the factories in 1935, the Hotchkiss 12-tonner, the medium Somua of 19 tons and the great Char B of 31. There was no split mind amongst their designers. These machines were designed for European war and for nothing else. The Somua could travel at 25 mph, was well armoured, and mounted a powerful 47 mm gun; the Char B was a giant, by the standards of 1935, and carried a giant’s punch in the shape of a genuine soixante-quinze. The later model, the Char B bis, could cruise at the respectable speed of about 18 mph, though its range was limited to about 90 miles. During the early Hitler years France led the world handsomely in tank design and construction. Unfortunately the French Army had no Broads or Hobarts to teach them how big formations should be handled. Radio equipment for them was not even ordered until November, 1939.

Everybody knew that Germany was surreptitiously building tanks in defiance of her Treaty obligations, for everybody had heard of the friend of a friend who, on a motoring holiday, had rammed one and found it to be made of cardboard. The German Army, in sober truth, was experimenting with small machines much like the light Vickers and only just working towards the heavier kind. Mention ‘German Tanks’ and the mind leaps to huge affairs like the Panther and the King Tiger. In 1935 these were still a long way into the future. The Panzer Divisionen began to form on the sly in 1934 with machines less effective than those in Hobart’s command. Their speed towards improvement, however, vastly exceeded anything in this country.

Here tanks were once again pushed to the bottom of the queue. The first task of the Army was the defence of these islands, and that meant in very large degree defence against the bomber. Much of the manpower that might have been available for an Expeditionary Force was switched into anti-aircraft guns and searchlights, though progress in these things also was lamentably slow. The second task was the defence of Egypt, which included keeping the peace between Arab and Jew in Palestine, the result of conflicting promises left over from the war. A new tank battalion, the 6th RTC, was raised in Egypt but it got nothing beyond some of the old tanks. The Army in India had to be kept up to strength and garrisons found for Hong Kong and Singapore; these began to look like something more than peacetime stations with the Japanese cutting loose on mainland China. Anything left over from these might be used for a Field Force on the Continent, but it was the lowest of priorities; and lowest of priorities for the Field Force was its tank element. The Army Estimates for 1934 were cut from forty millions to twenty millions. The estimates for 1914, computed in peacetime, had been just under twenty-eight millions.