IN 1934 THE ROYAL TANK CORPS had possessed the best machines in the world and the men who knew how they should be handled in battle. By 1938 all that had gone, save for the quality of the tank crews. The Army was 20,000 men short even of its Peace Establishment. Sir Edmund Ironside, about to leave for Gibraltar, wrote in his Diary that we had ‘obsolete medium tanks, no cruiser or infantry tanks, obsolete armoured cars and no light tanks apart from one unit in Egypt.’ There were a few light machines and armoured cars in India but they hardly counted. ‘This,’ he concluded, ‘is the state of our Army after two years warning. No foreign nation would believe it if they were told it.’

The warnings were clear enough. Fuller, long retired, had become a Fascist of high degree and as such had been invited to inspect both the Spanish Civil War and the new German formations. At the request of the General Staff he wrote of what he had seen. His letters made gloomy reading. The light tank was ‘a wretched little object’, while the Germans were producing powerful machines in great quantity. This was confirmed by Hotblack, now Military Attaché in Berlin. Mr Baldwin’s extra money was all being spent by Mr Chamberlain – ‘J’aime Berlin’, the French pronounced it – on anti-aircraft guns and the like. Even these, in 1938, were only noticeable by their absence.

Things were, however, on the move in the tank business. Dr Merrit was well on the way to overcoming the difficulties with the Christie. The solution seemed to lie with a form of modified version of the controlled differential, using light brakes which absorbed little power but retarded the track upon the side to which the driver sought to turn and transferred its energy into the other. It was to prove entirely successful, but not in 1938. Martel pressed on with a resurrected A9. Carden had left plans for a form of suspension, known in the trade as ‘the Bright Idea’ which was not as good as the Christie but still better than anything that had gone before. The first three marks were, in Martel’s words, ‘not successful’, but by the summer the prototype of a Mk IV came off the line and looked promising. Its top speed was only 23 mph and its armour no better than the 1918 Mk V but at least it carried a gun. The 2-pdr anti-tank gun, with a semi-automatic breech, was regarded as formidable. One was on exhibition at the Netheravon Wing of the Small Arms School and was hidden away in the Museum when the Japanese Military Attaché paid a call. An old horse artillery 13-pdr was put in its place and the Attaché’s chauffeur was observed making copious notes about it. The A9, originally conceived as a cheap version of the Vickers 16-tonner, behaved as cheap things do. It was not mechanically reliable.

Something in the nature of a close-support tank was also demanded and dust was blown off the plans for A10. As Vickers had no more capacity, contracts for building the A10, designed to carry a 3″ howitzer, were placed with several commercial companies. Inevitably very few were made by September, 1939, although the establishment provided for six of them to a battalion.

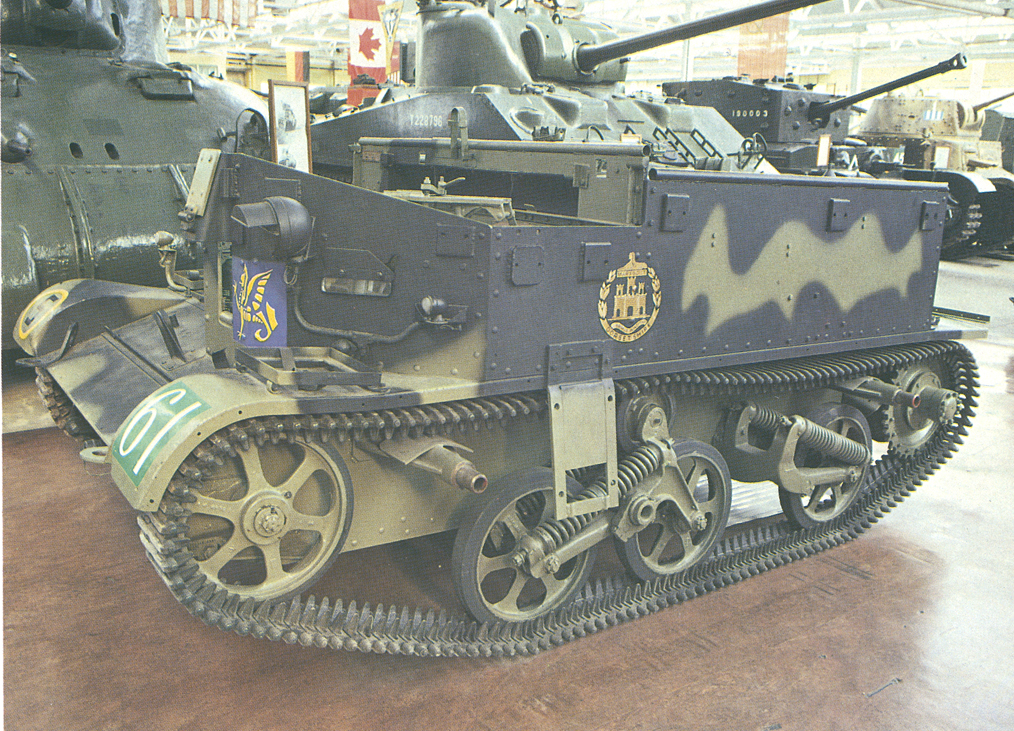

Last of the new breed was the A11, Elles’ ‘I’ tank and his legacy to the Corps. ‘I’ tanks, by their nature, need armour heavy enough to keep out more than rifle bullets and experiments were put in hand to find something thicker. It was soon found that protection from a 2-pdr shot demanded a thickness of 60 to 70 mm. Nobody had ever made a tank with armour anything like as thick, but it had to be done. A contract had been placed with Vickers as long ago as October, 1936, but progress had been slow. In March, 1938, the machine emerged. Such was the weight of the armour that it could only lurch along at 8 mph, the pace of a ‘Stop Me And Buy One’ ice-cream tricycle. A glance suggested at once that either the machine had been involved in a serious accident or that many vital parts were missing from the outside. It had a turret, but so small that it could only accommodate a single heavy machine-gun. The waddling gait called to mind Matilda, the name of a duck in a contemporary comic strip. It could as well have been Donald. Matilda it was, however, and it was the only infantry tank we had. It could absorb endless punishment but was so feebly armed that it could deal out none in return. The cruiser, on the other hand, could hit hard but any gun would kill it immediately. Matilda turned the scale at 11 tons, most of it armour. The Russians were near to completing their 47-ton, 20 mph KV1: the Germans already had, in large numbers, the PZKw III and the French their Char B bis. To comment on this state of affairs demands intemperate language. Only about fifty Matildas existed in September, 1939. A further fifty were promised by June, 1940.

There was no pattern to the business. Germany, by contrast, went to work systematically, The first tanks were small affairs, no better than the light Vickers. Each, however, was given a rigorous testing in every particular. That done, and every weak point discovered and corrected, the makers moved upwards to a bigger, faster, better-armoured and better-gunned machine. The British way was more eclectic; if a tank was unsatisfactory, then bring another even if it is worse. This state of affairs was to continue for a long time. Nobody suggested that we might buy superior tanks from France or build them here under licence. When Anthony Eden, who had done an attachment to the tanks as a TA officer, canvassed the idea he found no supporter.

French Tanks of 1939. The Somua S35.

Then came the humiliation of Munich. Time was certainly bought at the cost of honour; the fact remains that had we gone to war in 1938 we should have been soundly beaten and the Swastika would have been flying over London by Christmas. Possibly, before too long, over Washington and Moscow as well. Mr Wells, still active, coloured up the picture with his film The Shape Of Things To Come where the tower of St Martin’s-in-the-Fields crashes down upon the crowd in Trafalgar Square. Stories abounded about gases of unbelievable nastiness. The anti-aircraft element of the Army was increased first to four Divisions and finally to seven. Vickers concentrated their efforts on new and better guns for them. Tanks remained in their familiar place, at the end of the queue.

From 1936 onwards there had been White Papers and other papers about our continental commitment with much said about four Divisions and an Armoured Division. What actually existed was explained by Major-General Hawes in a letter to the Daily Telegraph published on 6 October, 1981. A fortnight before Mr Chamberlain went to Munich Colonel, as he then was, Hawes of the War Office G Staff took a party of officers to France to make arrangements for the reception of the British Field Force. It would have amounted to three infantry battalions, ten bomber squadrons from the RAF and nothing more. In such a state of affairs there was not a lot of value in talk of expanding torrents and great tank raids. The blame must go to successive Governments but His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition ought not to escape scot-free. The Leader of that Opposition was a former Tank Corps officer, Major Clement Attlee. His attitude is hard to understand, for he had a fine war record and his patriotism was never in question. Neither of these could, however, be said of some of his colleagues.

If war had come at Munich time the French Army would have had to fight alone. There was only one spot on the map which remained a British responsibility. Egypt was still reckoned in as much danger as in Lord Kitchener’s day and something had to be done to strengthen the defences. The 1936 Treaty limited the number of troops that might be kept there. The task was to make them more effective, for the Italians had, in the M13/40, a better tank than anything that could be put against it. Lord Gort sent for Hobart, then in the Staff Duties Directorate at the War Office, and sent him off to form an Armoured Division in Egypt while there was still time.

Hobart arrived a couple of days before Mr Chamberlain’s last call on Hitler. He was greeted by the Commander British Troops in Egypt with ‘I don’t know what you’ve come here for, and I don’t want you anyway’. This did not endear General Gordon-Finlayson to the tank expert; nor did it inhibit him from getting down to work. Hobart inspected his troops. There were two RTC battalions equipped with a few worn-out Vickers Mediums as the only thing more formidable than various Marks of the light tank. There was in addition a Mechanized Cavalry Brigade. On closer scrutiny this turned out to be the 11th Hussars, still clinging to their 1920 Rolls Royces, the 7th Hussars with an early model of the light tank of strident unreliability issued on their mechanization a year before and the 8th Hussars in Ford trucks. There was a mechanized Horse Artillery battery of 37 howitzers and a single battalion of lorried infantry.

From this mechanized scrap-heap Hobart began to build the formation that was to become the famous 7th Armoured Division. For something over a year he brought to bear his unequalled skill in matters of tank warfare and, as equipment trickled in, he began to see something like a genuine Division taking shape. His reward was to be sent home with an Adverse Confidential Report. The officers reporting on him were Sir Robert Gordon-Finlayson, about to go home himself in order to become Adjutant-General, and General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. Of the former Pownall wrote in his Diary that ‘It’s time he left Egypt where he has done much but has not succeeded in keeping up morale too well’. Sir Edward Spears dealt more suavely with the latter: ‘Military historians may discover in his decisions a sagacity which my own shortcomings no doubt prevented me from detecting.’ Few, if any, have accused ‘Jumbo’ Wilson of being amongst the Great Captains. Between the two of them they threw away the best commander of armoured troops in the British, perhaps in any, Army. Seventh Armoured had to manage without ‘Hobo’.

The dreadful year of 1938 passed into history. Early in the next one the War Office received a new Permanent Under Secretary who was something out of the ordinary run of Civil Servants. P. J. Grigg – never called other than ‘P.J.’ – had been a Gambardier, an officer in the Royal Garrison Artillery, during the Kaiser’s War and although much of his service had been of a financial kind, part of it in India, he enjoyed the advantage of having been Private Secretary to Mr Churchill with whom he remained in close touch. P.J. was reckoned the rudest man in the Civil Service and he feared nobody, Minister, General, Admiral or anything else. The impression he gained on arrival was one of confusion.

Official policy seemed to be that when war came the Army would not be expected to do more than defend these islands, mainly against air attack, and find garrisons for the usual places. In spite of the fact, explained by General Hawes, that we had no troops, it was decided early in 1939 that we should have to accept a land commitment in Europe and that much of the burden would have to fall upon the Territorials, starved of everything though they were. It began with a promise of two Divisions and later it was increased to four. There was no longer any mention of the Mobile, or Armoured, Division. This was hardly surprising, for it did not exist.

Mr Hore Belisha had ideas of his own. In March the ancient office of Master-General was abolished and its duties transferred to a civilian Ministry of Supply under the colourless Dr Leslie Burgin, assisted by Admiral Brown. They were not to be envied and Martel said, mildly enough, that ‘it took the Ministry a long time to find its feet’. This was undeniable in the matter of tanks. Nothing was on offer better than the A9, the A10 and the A 11. Production even of these was held up by friction between the soldiers and the engineers which resulted also in mechanical defects being allowed to go unrectified.

Vickers showed once more how the business could be done. When their 16-tonner had been turned down as too expensive, they had been asked to come up with something else. The plans produced in 1935 were once more rejected as showing something both too slow and insufficiently armoured. They redesigned it yet again with thicker armour and a new kind of track. The Valentine, not quite ready for production by September, was neither as well-protected as Matilda nor as fast as the Cruiser, but it was utterly reliable; probably the only British tank of the day about which this could be said. Before the war was over it had gone through nine marks. If the Ministry of Supply had adopted methods of quality control equal to those of Vickers much grief might have been saved.

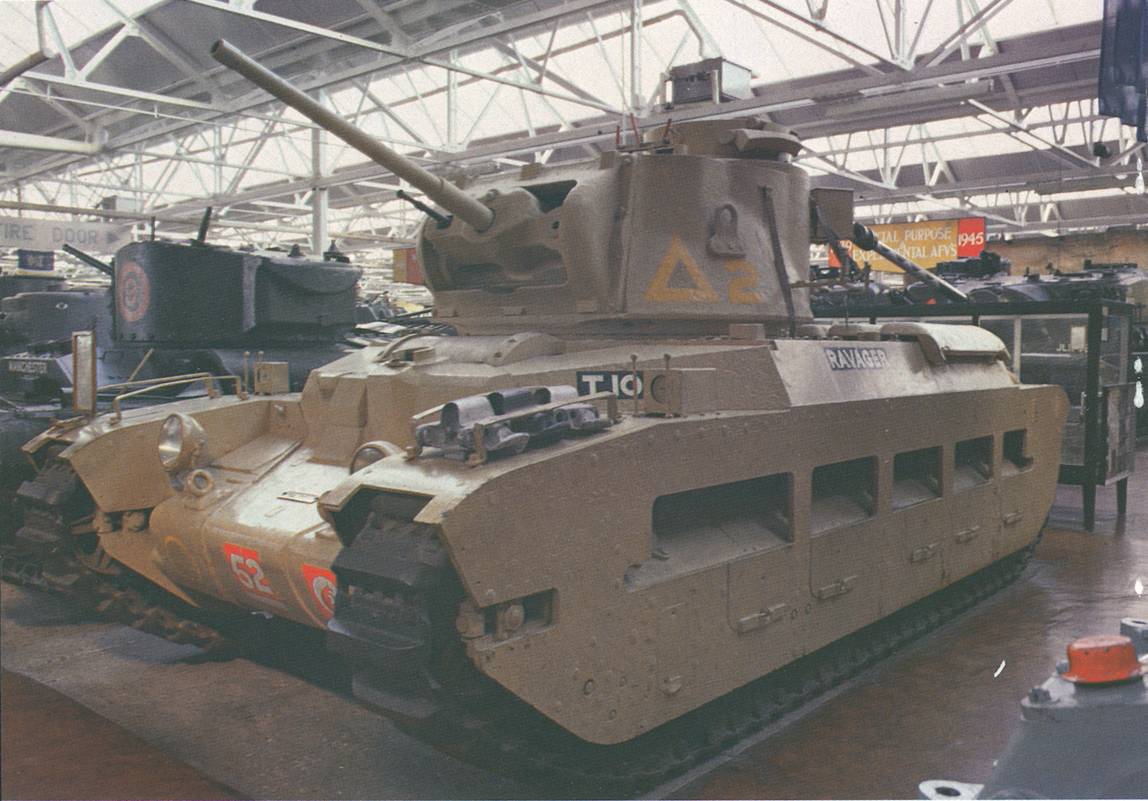

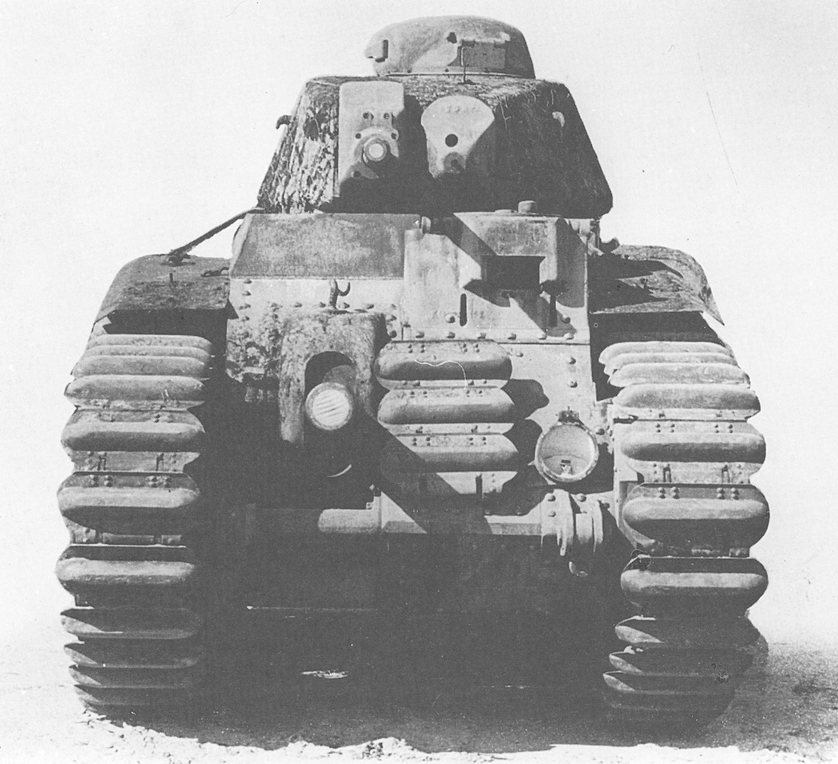

French Tanks of 1939. The Char B. Usually called by the Press ‘the French 50-ton (occasionally 70-ton) Tank’. Its actual weight was 33 tons.

In April, 1939, the month that saw the re-introduction of conscription, the cavalry rode sadly away. All line regiments, save only the Royals and the Greys, were mechanized; the old names were retained by Cavalry of the Line, along with eighteen Yeomanries, though all now became part of the Royal Armoured Corps. The RTC also changed into the Royal Tank Regiment, though this made no difference in practice, except that its precedence in the Army List was now ahead of the Royal Artillery. It was inevitable but it could not be expected to achieve universal popularity. The cavalry, on the whole, did not take unkindly to the change for war was in the offing and it had no place for horses. They set themselves to learn all about the Vickers Light Tank. All but the 12th Lancers, who were given a new armoured car. Bovington did not greatly care for the change, for it was a very professionally organized establishment and had no means of expanding to take over training masses of new and possibly reluctant entrants.

The A13, ancestor of the Cruiser Tanks.

On organization a kind of convention grew up. Divisional cavalry regiments were nothing new. The mechanized variety could at short notice be converted into Armoured Reconnaissance Brigades, though they would need a lot of training. What did not exist was the equivalent of the old Bermicourt Central Workshops. It was not until yet another new Corps, the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, came into existence that repair and maintenance ceased to be matters of great difficulty. Under the convention ex-cavalry regiments would be the light troops, doing what cavalry had always done, and the RTR would be the heavyweights.

At long last the old Vickers-Lewis-Hotchkiss-Madsen controversy was settled. When the infantry adopted the Czech ZGB light machine-gun and called it the Bren it was re-made to take the old rimmed .303 cartridge. The Armoured Corps also adopted it but in the original form, including the rimless .276 round. This was wise, for the old cartridge was far freer from stoppages than the new. Later a heavy, 15-mm model was taken over under the name of Besa. It proved a valuable weapon.

The tanks, under whatever name, remained a race apart, having little or no training in conjunction with other arms. Neither artillery nor RAF had time to spare for training in joint operations. The Germans made excellent practice in Spain with their JU87 dive bomber and made no secret of it. Vickers’ chief test pilot, Summers, was allowed to fly one and on his return home was rebuked by the Air Ministry for presumption. To criticize the RAF would be absurd; its plate was full with far more important matters.

Lack of interest in Army affairs did, however, inhibit the tanks’ effectiveness. The events of 1918 had shown how much need armour had for air support. The JU87 was highly effective as close-support artillery and further earned its keep by beating-up unarmoured units. Its effectiveness was mainly gained by spreading a kind of ‘Stukaschrecken’; steady troops soon came to rumble it for what it was – a machine that made fearsome noises but did little damage and had no taste for controlled rifle fire from the ground.

With war creeping nearer and tank production reckoned at no more than three or four a month, the Armoured Division was, says Martel, ‘dreadfully short of equipment’. The first A13s, the Christie Cruisers, began to dribble in from Nuffields but much work was needed on them before they could be called battle-worthy. The 2-pdr was a good enough weapon for the immediate future but armour was becoming thicker. Martel prudently arranged for drawings to be made of a 6-pdr which could be put into production as soon as the need arose.

Defence against tanks had been neglected even more than tanks themselves. The new infantry weapon was the Boys .55″ rifle. It was a slight, very slight, improvement on the German monster rifle of 1918. Given a tank a few paces away and unaware of the rifle’s presence it might, with luck, break a track-pin before the crew were seen off. In practice its main use was as a form of field punishment; it was heavy, awkward and entirely suitable to be given to the Company drunk to be carried as a penance. Then there were the mines. At the Hythe Wing of the Small Arms School instruction was given in these. They came in three sizes, the Mk I, the Mk II and the French mine. The first two resembled grey slab cakes, the last a good-sized wedding cake. The lectures began with a caution; the Mk I and Mk II were unreliable and the French one not much better. It was given out that the Army was buying a number of small French 25 mm anti-tank guns on handcarts. Few people appear to have come across one and the loss does not seem to have been great.

In 1938 and early 1939 there were numerous wild-eyed men about the place who claimed much knowledge of anti-tank makeshifts picked up during their service with the Communist International Brigade in Spain. Several of them published pamphlets about heroic miners from Galicia or the Asturias who had knocked out German tanks by means of bottles filled with petrol and other things or by flinging sticks of dynamite under their tracks. The trouble with the Tom Wintringhams was much the same as that with Mr Hore Belisha. Their demeanour did not inspire enthusiasm. The Bolshieness could have been overlooked; it was their cocksureness that people found rebarbative. Which was a pity, for they might have had something useful to sell.

Hore Belisha, with all his faults, did an honest best to make the Army better. Pay was increased and recruiting picked up. His efforts at re-clothing soldiers was less successful. Several specimens of a uniform proclaiming modernity were put on display; the most eye-catching was a kind of D.H. Lawrence gamekeeper suit complete with deerstalker hat, the whole carried out in mustard yellow. The idea was sensible enough, for far too much time was wasted with button-stick and blanco. The final choice was not pleasing. ‘Battle dress’, the top half of a golfer and the bottom of a skier along with the most ridiculous headdress imaginable, smacked more of Dartmoor than of Caterham. There was no escape and the Army went to France dressed as convicts.

In the busy month of April the first conscripts, all 20-year-olds, arrived. There were no weapons for them. Passers-by at Sir John Moore’s Shorncliffe Camp watched parties of young men practising Cuts 1, 2, 3 and 4 with cavalry sabres. It probably built muscle.

Nothing more came the way of the RAC. In April, on Ironside’s figures, tanks present with units numbered less than 45% of establishment. By 3 September there were exactly fifty ‘I’ tanks, all Matilda Is, out of the 450 on paper. The Territorial Army was doubled, a circumstance that the CIGS learnt for the first time from his morning paper. In August, 1914, Lord Kitchener had demanded to know whether the then Government knew what it was doing by going to war without an Army. This time it was far worse.

On 3 September, 1939, the long-expected blow fell and Foch’s Twenty Year Armistice was over. The Field Force went to France exactly as it had done in 1914 but neither as well-equipped nor so well trained. Its numbers were less than half those of Sir John French’s Army. The modern part of it, coming along by degrees, amounted to some Divisional cavalry regiments in useless light tanks or armoured cars. The Army Tank Brigade was made up of two battalions of Matilda Is, inexpugnable but powerless. The German General von Manstein later described its contribution as ‘quite insignificant’ and it is impossible to gainsay him.

His own Army mustered 3,200, mostly light machines but with about 300 of the formidable Mks III and IV and a number of the excellent Skoda T21S, the booty of Munich. France could call upon 2677, nearly 500 of them carrying a cannon of 47 mm or bigger. Even Japan was reckoned to own about 2,000. The Red Army had more than the rest of the world put together, something in the order of 20,000, but most of them were out-dated. The feebleness of Britain’s contribution passes belief. To be an ‘Old Contemptible’ is one thing: ‘Old Insignificant’ is quite another. The campaign of 1940 is outside the scope of this book. Suffice it to say that it did the Army some service. Along with masses of equipment, much of it obsolete. Hitler collected a good many middle-aged Lieutenant-Colonels and Majors who had outlived their usefulness.

In the course of a meeting on 16 May, 1940, Mr Lloyd George expressed his view of the matter to the CIGS, General Ironside: ‘Baldwin ought to be hanged’. Ironside made his own note that ‘Milne and Montgomery-Massingberd ought to be shot’. There was more to it than that.