“Anyone who’s diligently followed a written recipe only to have a terrible end result has felt the disconnect between tacit and explicit knowledge.”

Introduction

“Everybody works. They create documents and presentations. They schedule and attend events. They comment on other people’s work.”

∼ John Stepper, johnstepper.com

CALL IT WHAT YOU LIKE

When you were a kid, you likely had a math teacher or two who insisted that you “show your work.” It enabled him or her to see how you arrived at a final answer, what kind of thinking or steps got you there—and where you might have made a mistake. You can think of showing your work in any terms you’d like. Some call it “working out loud,” making work visible, making work discoverable, or narrating work. There are any number of approaches to showing work, from writing to talking to drawing to photographing and more. And now, with so many new, often free tools people like to use, it’s easier than ever before.

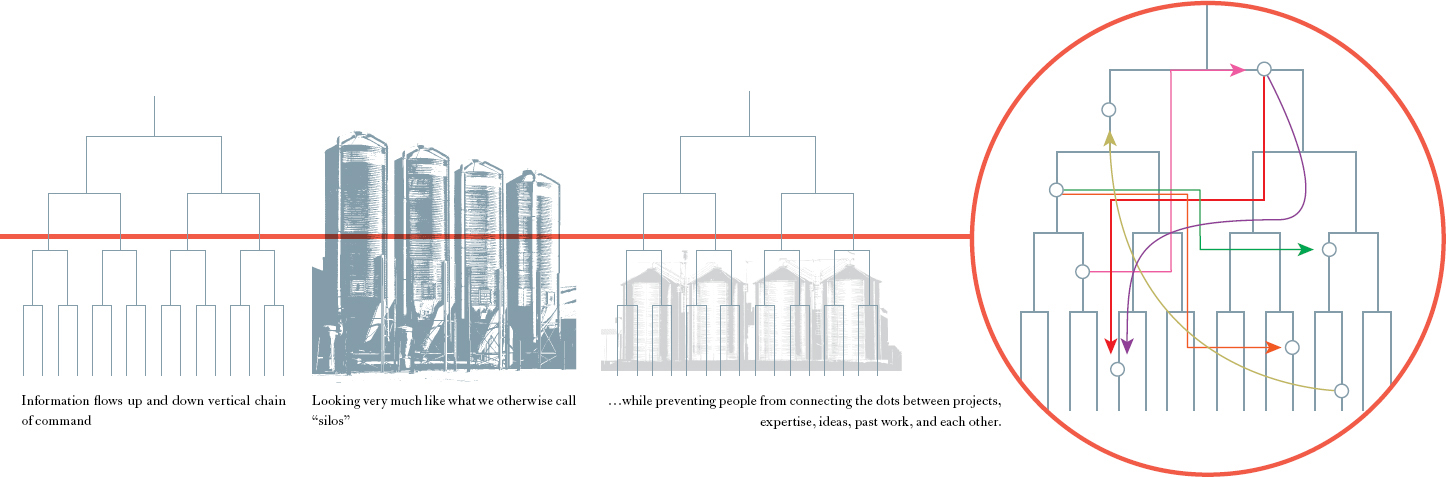

The Silo Problem

“If your dots are not observable/visible/transparent, then it’s impossible to connect them.”

∼BRIAN TULLIS

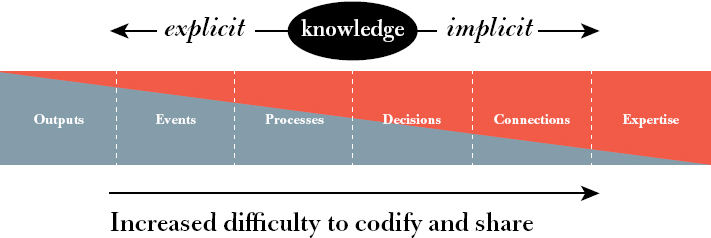

Codifying Knowledge

Thanks to Harold Jarche jarche.com

SHOWING YOUR WORK ISN’T NEW

A thousand years ago a wanderer who drew a map at journey’s end might be described as someone who “showed their work.” Apprenticeship in many ways offered a “show your work” approach, with the inclusion of instruction and feedback. Electronic tools introduced in the late 20th century made showing work much easier, as many of this book’s examples will show.

SHOWING YOUR WORK ISN’T MYSTICAL

One of the problems with the literature on showing work is that much of it is just too abstract and conceptual, with complex models and illustrations with maps and loops and actors. While the models may in some ways be accurate, and often in good intentions reflect the creators’ enthusiasm, they don’t seem to be very useful, else more people would be using them. They can also be daunting to the already-busy knowledge worker and the guy who fixes copy machines who works from his car most of the day.

As with the problem of “best practices,” which are really only best in their original context, the problem with models and formulas is that they often fit common circumstances in only the most abstract way. We see a similar issue with traditional ideas of “knowledge management” (KM), offering things like manufacturing schematics that look great on paper but don’t reveal stumbling points, exceptions, or extenuating circumstances. They don’t account for what can happen due to group dynamics, overengaged process owners, and business owners who need to be educated. Likewise, asking a worker to “just write down everything you do” can get us what, but doesn’t capture how. We are seduced by the idea that activities like this give us predictability and exact science.

There’s also a danger of the formula, or the tool, driving the train. A common criticism of KM is that it attempts to isolate the actor from the work, and the work from context. Sharing work should be an organic activity in everyday workflow, not some separate overengineered process that eventually proves to be nothing but more work.

IT’S NOT JUST FOR “KNOWLEDGE WORKERS”

I have been in the workforce for more than twenty years, mostly in areas like L&D and HR. If one thing has nagged at me for all that time, it is concerns about the segment of the workforce that is, it seems, uniformly marginalized. We focus on the “knowledge worker,” typically viewed as a college graduate working in a white collar job, at a desk, maybe at a desk in a cubicle, maybe at a desk in a home office. It’s fine to want to know what they know, but what about the rest of the workforce? As noted by Mike Rowe (http://profoundlydisconnected.com/), “No one ever stops to talk to the guys working on the film crew.”

You appreciate the hands-on or technical worker when you’ve tried a home repair a bit beyond your abilities, or despite following all directions failed at gardening. Anyone who’s diligently followed a written recipe only to have a terrible end result has felt the disconnect between tacit and explicit knowledge.

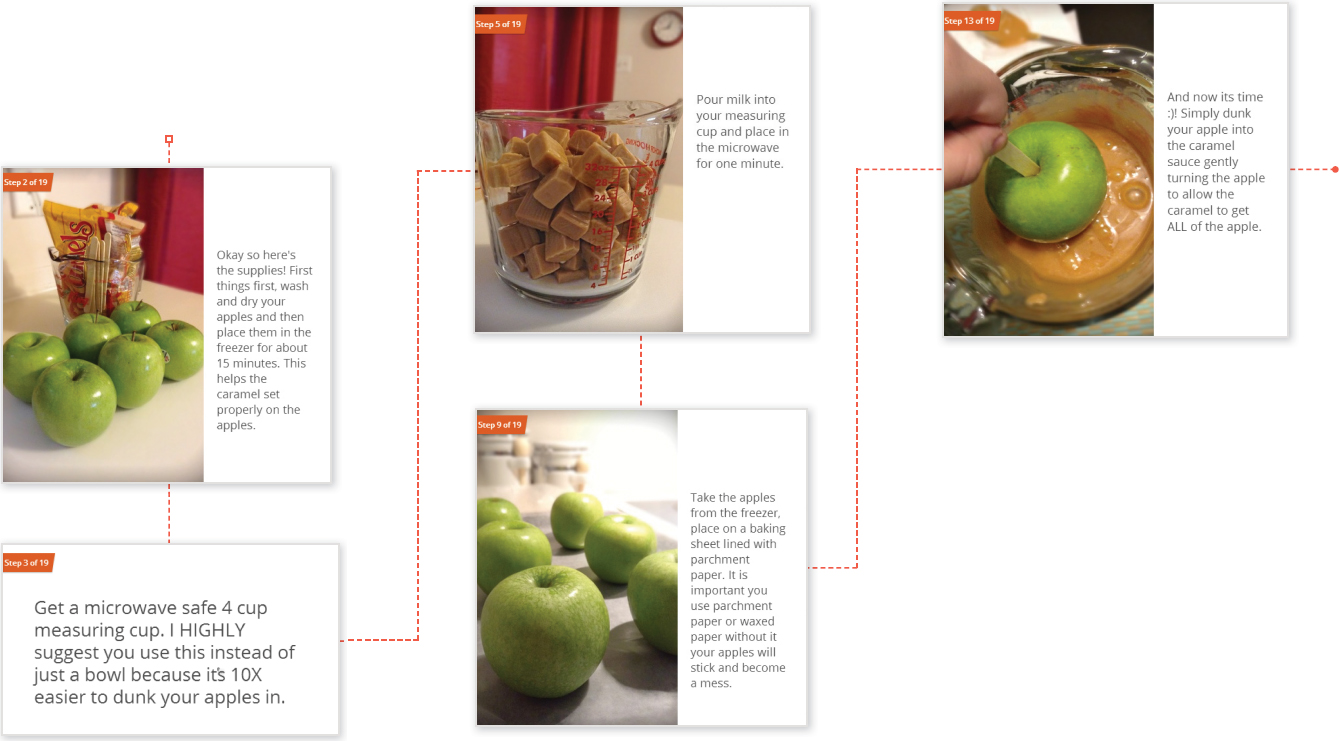

Here’s an example. Ask an expert to write down her recipe for caramel apples and this is what you’ll get:

Caramel Apples

- Remove stems from apple; push a craft stick into the top. Butter a baking sheet.

- Place caramels and milk in a microwave safe bowl. Microwave 2 minutes, stirring once. Allow to cool briefly.

- Roll each apple quickly in caramel sauce until well coated. Place on prepared sheet to set.

Here’s what happens when you ask an expert to show her work. This Snapguide on making caramel apples, from Bridget Burge’s Bridget’s Everyday Cooking (http://snapguide.com/guides/make-caramel-apples-1/) includes some things a novice might not know, and an expert might not think to write down:

Embracing a “Show Your Work” approach helps to include that segment of the workforce that’s so often been marginalized. Also: we can get a better understanding of what the tradesperson or the craftsperson does. How did the groundskeeper create that elephant topiary in front of the children’s wing at the local hospital? How did the pastry chef uniformly brown 400 Baked Alaskas to be served simultaneously? It’s important, for clear communication, to strip out extraneous information. But sometimes we strip out too much, and the bones we’re left with aren’t enough. As Brown and Duguid (1991) noted, taking out too much information about the daily reality of the work can leave you holding a map with no landmarks.

BEFORE ANYONE SAYS “YES, BUT...”

NO ONE SAID IT ALL HAD TO BE PUBLIC

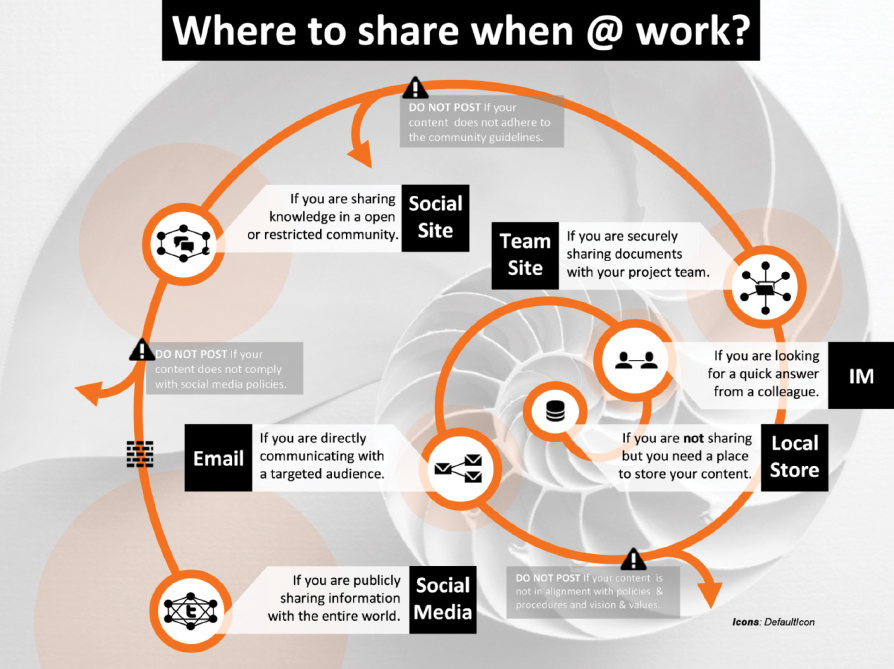

As we’ll see in the examples, everything doesn’t need to be shared everywhere. Proprietary information about a particular client may need to stay within a single work group. Details on fixing a particular water heater might be appropriate only for the company repair people scattered across North America. We don’t want people to be deluged with information that is truly relevant only to a few. The problem is, often those making that call don’t know who else might benefit. I once got a big work problem solved by a Twitter connection who teaches in China. And another by a consultant who specializes in helping retail and restaurant clients make their environments more comfortable for those with Asperger’s and autism. One of the challenges is to figure out where to best share work for maximum benefit to everyone.

NO ONE SAID IT HAD TO BE INSTAGRAM

It seems as soon as people start talking tools there is quickly a hue and cry against Facebook, or LinkedIn, or YouTube. While I see a lot of overcaution (Really? Your dress code and wellness program are secret? Can’t have cameras inside the workplace? Not even if it’s for a limited, “I need to photograph this cake” use? Ok, not even then? How about drawing? Have they banned drawing, too?) I agree that there need to be guidelines for where to share what. Here’s one approach:

Image courtesy Joachim Stroh

FINALLY: SHOWING YOUR WORK IS NOT ABOUT “INFORMATION”

The quest for “information” generates:

- Spreadsheets

- Meetings

- Quotas

- TPS reports

- Status updates

- Top-down dissemination

- Sacred story versus real story

- Only good news

“Information” alone is not enough. Adding the better information to more understanding of the exception, the behavior of the individual, the input of the expert, the workaround, the correction, the error helps generate a more robust picture that will help to inform and further refine enacting skillful work.

Remember: Communication over information. Conversation over tools.

So: Let’s get going.