Saying, “I don’t have time to narrate my work” is akin to saying, “I’m too busy cutting down the tree to stop and sharpen the saw.”

Workers: What’s In It For You?

As we’ll see in the “why people share” section, benefits may be as simple as wanting to show off a bit, wanting to pay a community back, or seeking feedback from peers in your field. Whether work gets shown or not, and how well, ultimately rests with the individual worker. Finding easy ways of getting it into the workflow—through quick videos, images instead of paragraphs on weekly reports, or a voice blog post from a mobile phone—may make all the difference.

Saying, “I don’t have time to narrate my work” is akin to saying, “I’m too busy cutting down the tree to stop and sharpen the saw.” (“I’m a busy knowledge worker. I don’t have time to think.”) You’re already talking about your work, probably more than you know. How can you make that more available to others?

A challenge is the reality of perceived productivity: clients pay us to produce, not reflect; organizations want activity, not journaling. But learning how and what (and when) to narrate work will, in the long run, help to streamline processes, help you develop an awareness of your own best practices, help you see where you are making mistakes, using flawed thinking, and spinning your wheels—and ultimately help improve your final work products and output. It won’t hurt if you ever decide to look for new employment, either. So what are some benefits individuals might find through showing their work?

ESTABLISHING CREDIBILITY/EXPERTISE

37signals designer Mig Reyes shares the importance of choosing the appropriate typeface to support your message. Who would you listen to if you wanted an expert on understanding how font affects design, and impact?

RAISING YOUR PROFILE

When Craig Taylor moved to a new company, one of the first requests he received was for help from a business unit wanting to improve their presentations. He took an existing slide deck and made changes, but better: he kept the old slides at the end and used the speaker note section to explain problems, what could be improved, and why he made changes. While another L&D unit might have created a 10–minute “good PowerPoint” tutorial, Craig gave back a real solution to a real work problem, in context. It was a good call. The unit was very happy with the final product. That, in turn, generated positive buzz about him, helped make him more visible to others, and established him as a go-to guy for this. It also let his new managers see what he could do.

IMPROVING PERFORMANCE

Working out loud can help build the connections vital to learning not just what is done but how work gets done, and how to get better at it. This happens outside of databases and APIs. SAP’s Sameer Patel offers an example he’s recently seen: “Networks of nurses looking to train each other not on standard policy stuff but tiny tips and tricks in the operating room that reduce latency and risk. These are contextual and very situational and where the ‘what’s in it for me’ is crystal clear to all participants.”

(From http://www.pretzellogic.org/blog/2013/06/09/networked-enterprises-social-business-forum-sbf13/)

CREATING DIALOGUE

Sometimes showing work isn’t just about declaring something but asking. On June 27, 2013, the author, looking for ideas about framing this book, asked for help from her Twitter-based #lrnchat colleagues. A 60-minute #lrnchat on “Show Your Work” generated forty-three pages of conversation around how, what, benefits of, and barriers to, narrating work.

GETTING HELP/SAVING TIME/NOT REINVENTING THE WHEEL

Getting help: Author’s story

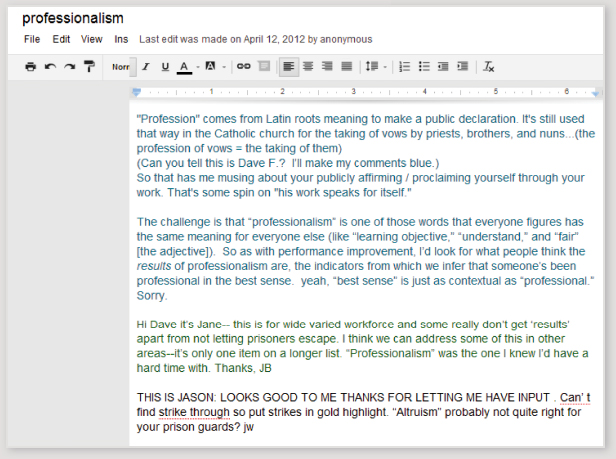

One afternoon a few years ago I received a phone call: The Governor’s office needed a writer to help with a “Code of Conduct” for all employees. For the state government workforce, that means kindergarten teachers and registered nurses and prison guards and kitchen workers and Highway Patrol officers, and everything in between. The Governor’s office sent over a draft code, a list of seven items they wanted to include, with a little supporting text. One of the items was “Professionalism.” I worked in state government for a long time, and every legislative session brings renewed interest in “performance management.” So I’ve been down the road of defining “professionalism” half a dozen times with very little consensus. It is a nebulous concept and tends to be something very much in the eye of the beholder. I knew coming up with a definition that covered this item would be a challenge.

So I decided to ask my Twitter-based PLN (personal learning network) for help. Before I went to work on the remaining six items, I set up a Google Doc, set it to be editable by anyone who accessed it, and tweeted the above message out:

Here’s the Google Doc after a few people had edited it:

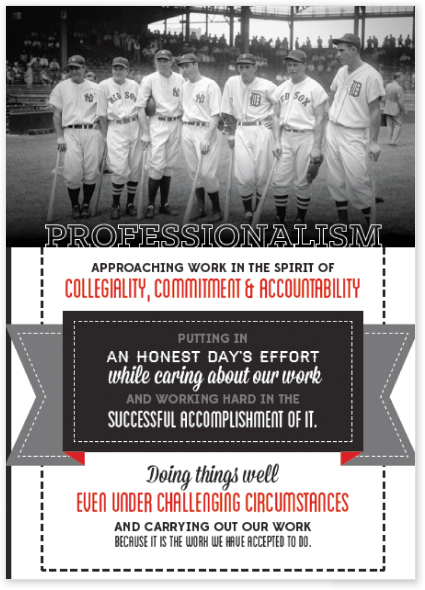

Meanwhile, I went on dealing with the rest of the items on the document. When I went back to check on “professionalism” the group had edited it down to a final definition. I copied and pasted it in and sent it verbatim to the Governor’s office.

Good? Yes. Appropriate for kindergarten teachers, prison guards, and kitchen workers? Yes. Better than I could have done on my own? YES.

Most people who know me wouldn’t expect this to be the kind of task that crosses my path, as I am most often involved in workplace learning matters. Saying “this is what I do, this is what I’m working on, and I need some help” will usually get you just that. Even better: It can create something others can use. When I showed this during a webinar, so many people asked for a copy of it that I tweeted it back out again and put it on a Pinterest board. It has also spread geographically: I used this as an example during a “Show Your Work” conference presentation in Chicago on September 20, 2013. The following Monday I received an email from a conference attendee who’d taken the idea home with him to Australia:

GETTING HELP: NEW WAYS OF WORKING AND COMMUNICATING AT YAMMER

Yammer’s Paul Agustin found that the move to Yammer changed his perception of how work gets done and how effective communication looks: “In my previous jobs the communication has followed a slow and inefficient path, like: Managers delegate work, information went back and forth, and data resided in email or a shared drive with no real collaborative abilities. Yammer uses a new model: it’s a completely different way of communicating. For instance, I’m currently working on a project in New York with a colleague in San Francisco. We use real-time collaborative notes. Someone gets @mentioned (at mentioned) in the conversation to draw them in. Allison in Arizona sees it, chimes in, and suggests someone else.”

Another advantage? Time. More from Paul Agustin: “Well, say you’re working on a course for developers. I can set up a group specific to that topic and ask for input. People can @each other to pull the right expertise in. They can provide insight on customer needs and experiences in the field. This way of working is MUCH faster. The old way it would have taken me a YEAR to get all this information. This way it takes days.”

People like to be asked for their opinions and ideas; showing your work can be another avenue for creating dialogue and getting feedback. Thinking about how you’re asking is a way both of getting help and letting them know what you do. Here’s an example from IBM’s Luis Suarez.

“Quite often the answers to problems that are plaguing you can be gained by educating someone else about the problems you face . . . during the process, you will see the answers for yourself.”

WASKO & FARAJ, 2000, p. 167

AN ASIDE: PUBLIC V PRIVATE?

Is there really a reason the conversation about “professionalism,” or Luis’s request for help with a presentation, should have been locked inside a firewall? Really? If it saves time and gets you a good result, and has nothing to do with proprietary information or potential profit . . . does is really have to be private? Weigh risks and payoffs: In the “code of conduct” example, is the value of protecting the organization’s code of conduct from public viewing so important that the better input from outside wasn’t worth seeking? Is there something so proprietary that it can’t be shared for reuse? Are there circumstances when it would make sense to have your public or your customers help you develop your code of conduct?

REPLACING RÉSUMÉ WITH SOMETHING MORE MEANINGFUL

A portfolio or other document is more than just a résumé listing skills or even accomplishments: It shows how you think, why/how you make decisions, how you work, and what leads to what results.

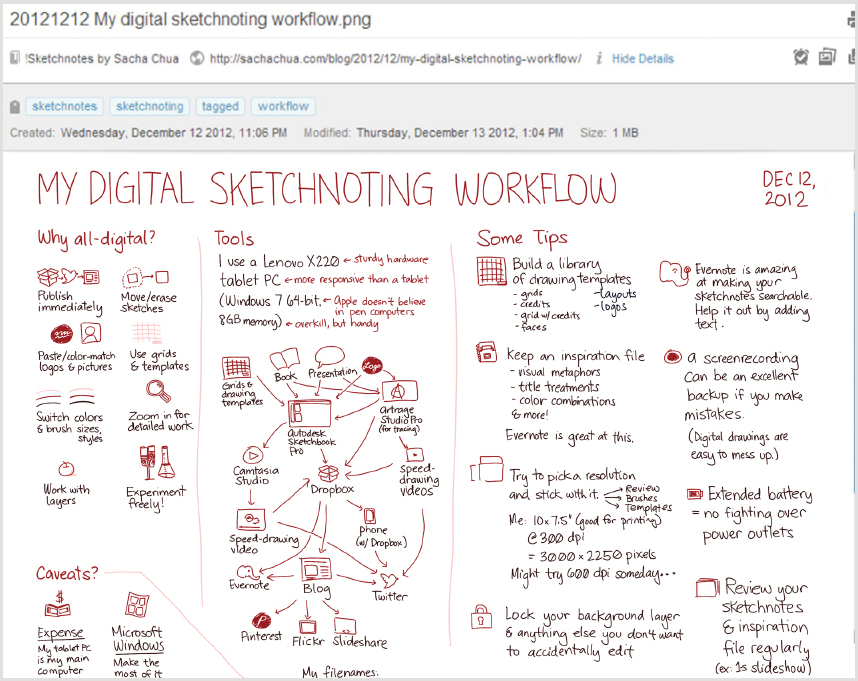

It’s not just “I can do this” but “See? I can do this.” The best can show not just final products but why/how you got there. Look at the difference in these two job candidates. In the second sample, a workflow outline from professional sketchnoter Sacha Chua, we see not only a finished product but documentation of how she did it. And she makes this available to the public via a shared Evernote notebook.

What else do you need to know about Sacha Chua? Can you see how she does what she does? Do you have a good view of her final product? Do you really think a résumé would tell you more? Think about the ensuing job interview: who seems more likely prepared with good answers?

(By the way: The author was recently involved in a hiring situation with the goal of bringing on an e-learning developer. Half of the candidates did not have portfolios available. Who would you choose to interview—or not?)

EXPLAINING YOUR THINKING HELPS YOU LEARN

The report of a Vanderbilt University study published in 2008 discusses an experiment in which young children were shown a series of patterned bugs and asked to guess the next one in the sequence. The children were divided into three groups: one group was asked to simply state the right answer, another to describe their thought process quietly to themselves, and the third to explain their reasoning to their mothers. All three groups were then given another, more advanced pattern test. Researchers found the group that had explained answers to their mothers did better on the more difficult test. Bottom line: When we’re asked to articulate ideas to other people, we learn better.

(B. Rittle-Johnson, M. Saylor, K. Swygert. (2008). Learning from explaining: Does it matter if mom is listening? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 100(3), pages 215–224.)

TEACHING OTHERS IMPROVES PRACTICE

Teaching others—whether hands-on as with decorating cookies, or through providing a demonstration like one offered by topiary artist Pearl Fryar—forces us to pay more attention to how we do what we do. Rather than just say, “This is what I do,” saying, “This is how I do that” brings about reflection and helps us to articulate specific behaviors and detailed steps. In other words: teaching helps you learn.

REFLECTION IMPROVES PRACTICE

Reflective practice is a challenge: we are all busy, and it is human nature to finish one thing and move on to the next, especially when working against deadlines or other pressures. But just taking a moment to say, “What went well? What would I do differently next time?” Can make the next time, and the time after that, go more quickly or smoothly or successfully.

There are a number of disciplines that require, particularly during training, documentation of reflections. Student and entry-level social workers, lawyers, and teachers, for example, are often tasked with journaling or recapping activities and commenting on them. This helps to both capture what happened as well as offer the time and space to develop additional perspectives and alternative explanations or questions. For instance, see what a student nurse wrote.

“Reflect on what you’re really doing all day: Email is not work.”

∼JEFFREY ZOLLER via Twitter

AN ASIDE: TIPS FOR BECOMING MORE REFLECTIVE

One of the goals of the reflective practice for students is the need for them to develop their own “internal supervisor”: a lawyer doesn’t have a boss watching her in court; a clinical social worker conducting family therapy won’t often have an observer standing by to give feedback. For many of us, learning to evaluate our own performance, and repeat or correct it as needed, is critical to successful practice.

EXERCISE 1

If reflective practice is new for you, begin by ending a task, particularly a big one, by asking yourself some basic questions. Consider things like:

What do I know now that I didn’t know when I started?

Why did this particular (event, barrier, success, accident) happen? How can it be explained?

What can I do differently next time? How could I have made this go (faster, better, more smoothly)?

What political issues emerged ?

A problem I ran into was ___________________________

I fixed it/overcame it/circumvented it by ________________________

How did the outcome measure up to my expectations?

How well did the actual reflect my estimates on time, challenges, difficulty, people?

I could not fix/overcome/circumvent it because __________________

Did this highlight any deficiencies in my preparation/training/skill level? What do I need to do to correct that?

What assumptions did I make? How valid were these? How did they affect what I did?

What do I know about ________ now that I didn’t know when I started?

Why did ___________ happen? How can it be explained?

What did I learn from this?

EXERCISE 2

Remember the lesson of the patterned bug images and saying it out loud. Linda Kirkman, struggling with managing the content of her thesis, borrowed from ideas on storyboarding and found it most helpful to talk it through out loud, even though the only listener was an admittedly somnolent cat. Her inspiration came from http://patthomson.wordpress.com/2013/03/28/story-boarding-the-thesis-structure/.

Photo courtesy Linda Kirkman (@lindathestar).

Linda says, “The talking really helped me make sense of different ideas. I asked questions such as, ‘Why does that go there, why not elsewhere? What is the boundary for that idea? What makes it relevant?’ If I had just thought silently about the lacement of the points within the themes it would have taken longer and not been as effective. There is something about speaking the thoughts that clarifies them. I felt less of a dork talking to yourself by imagining the somnolent tortoiseshell cat Charlotte as an audience.”

EXERCISE 3

Make yourself a quick printable template and keep a stack handy. Read it over and answer the questions as you complete big tasks, new tasks, or challenging conversations.

While it’s tempting to do these exercises and keep them only to yourself, stop and ask, “Who else might benefit from this?” Several examples in this book show the power of talking through mistakes made and ways to avoid them next time. Other practitioners would likely find that more useful than “here is my dazzling thing I did.”

For an in-depth look at the value of reflective practice—and writing about it—see Atul Gawande’s Complications, an excellent first-person account of a new surgeon’s experience with learning to learn.

PAYING IT FORWARD

Matt Thompson, editorial product manager at NPR, offers some nice commentary about this on the Poynter.Org blog in a piece called “6 Reasons Journalists Should Show Your Work While Learning”:

“It’s only right to pay it forward. Whether or not you know it, you’ve benefited from others who’ve shown their work. This article you’re reading was published by an open-source CMS, using open-source database software. There’s a better-than-even chance you’re using an open-source browser to read it. As Germuska points out, the Internet was built by people saying, ‘Here’s what I did. How might it work for you? Make it better.’ And certainly, if you’ve learned to code or you intend to start, you’ll have relied quite a bit on the kindness of strangers. What goes around should come around.”

http://www.poynter.org/how-tos/digital-strategies/150243/6-reasons-journalists-should-show-your-work-while-learning-creating/. (See this book’s section on “Why People Share” for more on this.)

BENEFITS TO YOU

The benefits of showing your work range from career enhancement to paying back (and forward). Note throughout the book the ways in which others are doing this. Few of us are eloquent and prolific Richard Edelmans; some of us may prefer a quick narrated slideshow, a few tweets, or a 6-second Vine video. Some may write narratives while others post by voice. The trick is finding ways to get it into your workflow—making it part of everyday practice without it being another onerous chore. The bulk of this book offers examples that should help provide inspiration as well as ideas for easy means of getting showing your work into your work flow.