THE HISTORY OF THE FIRST CALENDER, THE SON OF A KING.

THAT you may know, madam, how I lost my right eye, and the reason why I have been obliged to take the habit of a calender, I must begin by telling you, that I am the son of a King. My father had a brother, who, like himself, was a monarch, and this brother ruled over a neighbouring state. He had two children, a son and a daughter; the former of whom was about my age.

“When I had finished my education, and the King, my father, had allowed me a proper degree of liberty, I went regularly every year to see my uncle, and passed a month or two at his court, after which I returned home. These visits produced the most intimate friendship between the Prince, my cousin, and myself. The last time I saw him he received me with demonstrations of the greatest joy and tenderness; indeed he was more affectionate than he had ever yet been; and wishing one day to amuse me by a great entertainment, he made extraordinary preparations for it. We remained a long time at table; and after we had both supped, he said to me, ‘My dear cousin, you can never imagine what has occupied my thoughts since your last journey. I have employed a great number of workmen in carrying out the design I meditated. I have erected a building, which is just finished, and we shall soon be able to lodge there: you will not be sorry to see it; but you must first take an oath, that you will be both secret and faithful: these two things I must require of you.’

“The friendship and familiarity in which we lived, forbade me to refuse him any thing; without hesitation, therefore, I took the oath he required. ‘Wait for me in this place,’ he cried, ‘and I will be with you in a moment.’ He did not in fact detain me long, but returned bringing with him a lady of very great beauty, and most magnificently dressed. He did not tell me who she was, nor did I think it right to inquire. We again sat down to the table with the lady, and remained there some time, talking of different things, and emptying goblets to each other’s health. The Prince then said to me: ‘We have no time to lose; oblige me by taking this lady with you, and conducting her by yonder path to a place, where you will see a tomb, newly erected, in the shape of a dome. You will easily know it, as the door is open. Enter there together, and wait for me; I will join you directly.’

“Faithful to my oath, I did not seek to know more. I offered my hand to the lady; and following the instructions which the Prince my cousin had given me, I conducted her safely to our destination by the light of the moon. We had scarcely arrived at the tomb, when we saw the Prince, who had followed us, and who appeared with a vessel full of water, a shovel or spade, and a small sack, in which there was some mortar. With the spade he destroyed the empty sarcophagus, which was in the middle of the tomb; he took the stones away, one by one, and placed them in a corner. When he had taken them all away, he made a hole in the ground, and I perceived a trap-door in the pavement. He lifted it up, and disclosed the beginning of a winding staircase. Then addressing himself to the lady, my cousin said, ‘This is the way, madam, that leads to the place I have mentioned to you.’ At these words the lady approached and descended the stairs. The Prince prepared to follow her; but first turning to me, he said, ‘I am infinitely obliged to you, cousin, for the trouble you have had; receive my best thanks for it, and farewell.’ ‘My dear cousin,’ I cried, ‘what does all this mean?’ ‘That is no matter,’ he answered, ‘you may return by the way by which you came.’

“Unable to learn anything more from him, I was obliged to bid him farewell. As I returned to my uncle’s palace, the fumes of the wine I had taken began to affect my head. I nevertheless reached my apartment, and retired to rest. On waking the next morning, I made many reflections on the occurrences of the night before, and recalled all the circumstances to my recollection of so singular an adventure. The whole appeared to me to be a dream. I was so much persuaded of its unreality, that I sent to know if the Prince, my cousin, had risen. But when they brought me word, that he had not slept at home, and that they knew not what was become of him, and were very much distressed at his absence, I concluded that the strange adventure of the tomb was too true. This afflicted me very much; and shunning the gaze of all, I went secretly to the public cemetery, or burial-place, where there were a great many tombs similar to that which I had before seen. I passed the day in examining them all, but was unable to discover the one I sought. I spent four days in the endeavour, but without success.

“It is necessary for me to inform you that the King, my uncle, was absent during the whole of this time. He had been away for some time on a hunting party. I was very unwilling to wait for his coming back, and having requested his ministers to apologize for my departure, I set out on my return to my father’s court, from which I was not accustomed to make so long a stay. I left my uncle’s ministers very much distressed at the unaccountable disappearance of the Prince; but as I could not violate the oath I had taken to keep the secret, I dared not lessen their anxiety, by revealing to them any part of what I knew.

“I arrived in my father’s capital, and contrary to the usual custom, I discovered at the gate of the palace a numerous guard, by whom I was immediately surrounded. I demanded the reason of this; when an officer answered, ‘The army, Prince, has acknowledged the grand vizier as King, in the room of your father, who is dead; and I arrest you as a prisoner, in the name of the new monarch.’ At these words, the guards seized me, and led me into the usurper’s presence. Judge, madam, what was my surprise and grief!

“This rebellious vizier had conceived a strong hatred against me, and had for a long time cherished it. The cause of his hostility was as follows: When I was very young, I was fond of shooting with a cross-bow. One day I carried my weapon to the upper part of the palace, and amused myself with it on the terrace. A bird happened to fly up before me; I shot at it, but missed; and the arrow, by chance, struck the vizier on the eye, and destroyed the sight, as he was taking the air on the terrace of his own house. As soon as I was informed of this accident, I went and made my apologies to him in person. Nevertheless he cherished a strong resentment against me, and gave me proofs of his ill-will on every opportunity. Now that he found me in his power, he evinced his hatred in the most barbarous manner. As soon as he saw me, he ran towards me with looks of fury, and digging his fingers into my right eye, he tore it from the socket. And thus did I become half blind.

“But the usurper did not confine his cruelty to this despicable action. He ordered that I should be imprisoned in a sort of cage, and carried in this manner to some distant place, where the executioner was to cut off my head and to leave my body to be devoured by birds of prey. Accompanied by another man, the executioner mounted his horse, and carried me with him. He did not stop till he came to a place suited for the fulfilment of his design. I managed, however, to excite his compassion, by entreaties, prayers, and tears. ‘Go,’ said he to me, ‘depart instantly out of the kingdom, and take care never to return; if you do, you will only encounter certain destruction, and will be the cause of mine.’ I thanked him for the mercy he showed me: and when I found myself alone, I consoled myself for the loss of my eye, with the reflection that I had just escaped a greater misfortune.

“In the condition to which I was reduced, I could not travel very fast. During the day, I concealed myself in unfrequented and secret places, and journeyed by night as far as my strength would permit me. At length I arrived in the country belonging to the King, my uncle; and I proceeded directly to the capital.

“I gave him full particulars of the dreadful cause of my return, and explained the miserable state in which he saw me. ‘Alas!’ cried he, ‘was it not sufficient that I have lost my son; but must I also learn the death of a brother, whom I dearly loved; and find you in the deplorable state in which I see you now!’ He informed me of the distress he had suffered, from his failure to obtain any tidings of his son, in spite of all the inquiries he had made, and all the diligence he had used. The tears ran from the eyes of this unfortunate father as he gave me this account; and he appeared to me so much afflicted, that I could not resist his grief; nor could I keep the oath I had taken to my cousin. In short, I related to the King everything that had occurred.

“He listened to me with some appearance of consolation, and when I had finished, he said, ‘Dear nephew, the story you have told me, affords me some little hope. I well know that my son built such a tomb, and I know very nearly on what spot it was erected. With the recollection which you may have preserved, I flatter myself we shall be able to discover it. But since he has done all this so secretly, and required you also not to reveal the fact, I am of opinion that we two only should make the search, that the circumstance may not be generally known and talked of.’ The King had also another reason, which he hid from me, for wishing to keep this a secret. This reason, as the conclusion of my history will show, was a very important one.

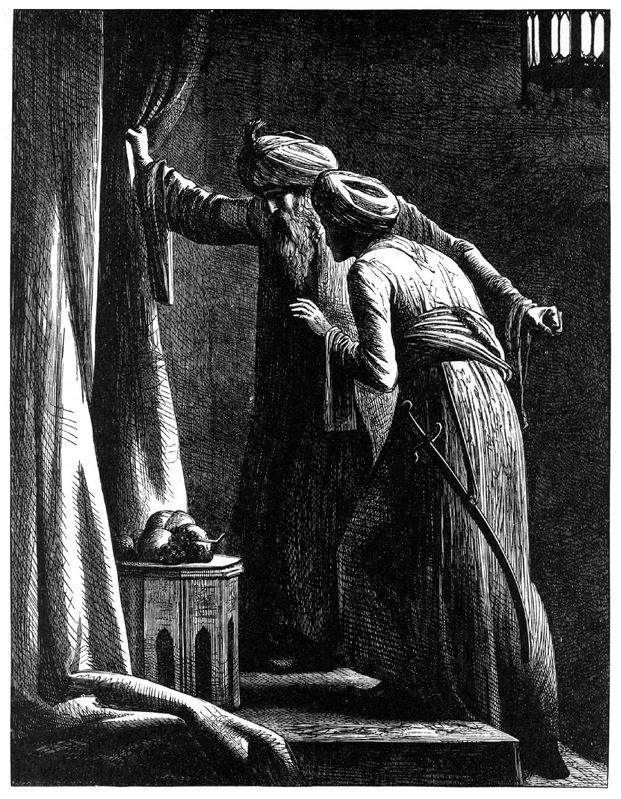

“We disguised ourselves, and went out by a garden gate, which opened into the fields. We were fortunate enough very soon to discover the object of our search. I immediately recognized the tomb, and was the more rejoiced, as I had once so long and so vainly endeavoured to find it. We entered, and found the iron trap-door shut down upon the opening to the stairs. We had great difficulty in lifting it up, because the Prince had cemented it down with the lime and the water he carried with him when I saw him last: at length, however, we raised it. My uncle was the first who descended; and I followed. About fifty steps brought us to the bottom of the stairs, to a sort of ante-room, which was full of a thick smoke, very unpleasant to the smell, and which obscured the light thrown from a very brilliant lamp.

The King discovers the dead body of his son.

“From this ante-chamber we passed on to one much larger, the roof of which was supported by large columns, and illuminated by many lights. In the middle of the apartment, there was a cistern, and on each side we observed various sorts of provisions. We were much surprised to find no one here. Opposite to us, there was a raised sofa with an ascent of some steps, and beyond this there appeared a very large bed, the curtains of which were closely drawn. The King went up to the bed, and opening the curtains revealed the Prince, his son, reclining upon it with the lady; but both were burnt, and charred black, as if they had been thrown on to an immense fire, and had been taken off before their bodies were consumed. What surprised me even more than this sight itself was, that my uncle did not evince any sorrow or regret at seeing that his son had thus lamentably perished. He spat on the dead face, and cried in an angry voice: ‘Such is thy punishment in this world!—but thy doom in the next will be eternal! ’ Not satisfied with this terrible speech, he pulled off his slipper, and struck his son an angry blow on the cheek.

“I cannot express the astonishment I felt at seeing the King, my uncle, treat his dead son in that manner. ‘Sir,’ said I to him, ‘however violent my grief may be at beholding this heartrending sight, yet I cannot yield to it without first inquiring of your Majesty, what crime the Prince, my cousin, can have committed, to deserve that his lifeless corpse should be insulted thus?’ The King replied: ‘Nephew, I must inform you, that my unworthy son loved his sister from his earliest years, and was equally beloved by her. I rather encouraged their rising friendship, because I did not foresee the danger that was to ensue. And who could have foreseen it? This affection increased with their years, and reached such a pitch, that I dreaded the consequences. I applied the only remedy then in my power. I severely reprimanded my son for his conduct, and represented to him the horrors that would arise, if he persisted in it; and the eternal shame he would bring upon our family.

“ ‘I talked to his sister in the same manner, and shut her up, that she should have no further communication with her brother. But the unhappy girl had tasted of the poison; and all the obstacles that my prudence suggested, only irritated her passion, and that of her brother.

“ ‘My son, convinced that his sister continued to love him, prepared this subterranean asylum, under pretence of building a tomb, hoping some day to find an opportunity of getting access to the object of his flame, and concealing her in this place. He chose the moment of my absence to force his way into the retreat of his sister, which is a circumstance that my honour will not allow me to publish. After this criminal proceeding he shut himself up with her in this building, which he furnished, as you perceive, with all sorts of provisions. But Allah would not suffer such an abominable crime to remain unchastised; and has justly punished both of them.’ He wept bitterly as he said these words, and I mingled my tears with his.

“After a pause, he cast his eyes on me; ‘Dear nephew,’ resumed he, embracing me, ‘If I lose an unworthy son, I may find in you a happy amends for my loss.’ The reflections which this speech called forth, on the untimely end of the Prince and the Princess, again drew tears from us both.

“We reascended the same staircase, and quitted this dismal abode. We put the iron trapdoor in its place, and covered it with earth and the rubbish of the building; to conceal, as much as possible, this dreadful example of the Divine anger.

“We returned to the palace before our absence had been observed, and shortly after we heard a confused noise of trumpets, cymbals, drums, and other warlike instruments. A thick dust, which obscured the air, soon informed us of the cause, and announced the arrival of a formidable army. The same vizier who had dethroned my father, and had taken possession of his dominions, now came with a large number of troops, to seize my uncle’s territory.

“The King, who had only his usual guard, could not resist so many enemies. They invested the city, and as the gates were opened to them without resistance, they soon took possession of it. They had not much difficulty in penetrating to the palace of the King, who attempted to defend himself; but he fell, selling his life dearly. For my part, I fought for some time; but seeing that I must surrender if I continued to resist, I retreated, and had the good fortune to escape, taking refuge in the house of an officer of the King, on whose fidelity I could depend.

“Overcome with grief, and persecuted by fortune, I had recourse to a stratagem, as a last resource to preserve my life. I shaved my beard and my eyebrows, and put on the habit of a calender; and thus disguised left the city without being recognized. After that, it was no difficult matter for me to quit the dominions of the King my uncle, by unfrequented roads. I avoided the towns, till I arrived in the empire of the powerful Sovereign of all true Believers, the glorious and renowned caliph Haroun Alraschid, when I ceased to fear. I considered what plan I should adopt, and I resolved to come to Baghdad, and throw myself at the feet of this great monarch, whose generosity is everywhere admired. I shall move his compassion, thought I, by the recital of my eventful history; he will no doubt commiserate the fate of an unhappy Prince, and I shall not implore his assistance in vain.

“At length, after a journey of several months, I arrived to-day at the gates of the city: when the evening came on, I entered the gates, and after I had rested a little time to recover my spirits, and settle which way I should turn my steps, this other calender, who is sitting next me, arrived also. He saluted me, and I returned the compliment. ‘You appear,’ said I, ‘a stranger like myself.’ ‘You are not mistaken,’ replied he. At the very moment he made this answer, the third calender, whom you see now, came towards us. He greeted us, and stated that he, too, was a stranger, and had just arrived at Baghdad. Like brothers we united, and resolved never to separate.

“But it was late, and we did not know where to seek a lodging in a city where we never had been before. Our good fortune brought us to your door, and we took the liberty of knocking; you have received us with so much benevolence and charity, that we cannot sufficiently thank you. This, madam, is what you desired me to relate; thus it was that I lost my right eye; this is the reason I have my beard and my eyebrows shaved, and why I am at this moment in your company.

“Enough,” said Zobeidè, “we thank you, and you may retire, whenever you please. The calender excused himself from obeying this last request, and entreated the lady to allow him to stay, and hear the history of his two companions, whom he could not well abandon; he also begged to hear the adventures of the three other persons of the party.

“The history of the first calender appeared very surprising to the whole company, and particularly to the caliph. The presence of the slaves, armed with their scimitars, did not prevent him from saying in a whisper to the vizier, ‘As long as I can remember, I never heard any thing to compare with this history of the calender, though I have been all my life in the habit of hearing similar narratives.’ The second calender now began to tell his history; and addressing himself to Zobeidé, spoke as follows:—