THE HISTORY OF THE LITTLE HUNCHBACK.

IN the city of Casgar, which is situated near the confines of Great Tartary, there formerly lived a tailor, who had the good fortune to possess a very beautiful wife, between whom and himself there existed the strongest mutual affection. One day, while this tailor was at work in his shop, a little hunchbacked fellow came and sat down at the door, and began playing on a timbrel, and singing to the sound of this instrument. The tailor was much pleased with his performance, and resolved to take him home, and introduce him to his wife, that the hunchback might amuse them both in the evening with his pleasant and humorous songs. He therefore immediately proposed this to the little hunchback, who readily accepted the invitation; and the tailor directly shut up his shop, and took his guest home with him.

“So soon as they reached the tailor’s house, his wife, who had already set out the table, as it was near supper-time, put before them a very nice dish of fish which she had been dressing. Then all three sat down; but in eating his portion the little hunchback had the misfortune to swallow a large fish-bone, which stuck fast in his throat, and almost instantly killed him, before the tailor or his wife could do anything to assist him. They were both greatly alarmed at this accident; for, as the mishap had happened in their house, they had great reason to fear it might come to the knowledge of some of the officers of justice, who would punish them as murderers. The husband, therefore, devised an expedient to get rid of the dead body.

“He recollected that a Jewish physician lived in his neighbourhood; and he formed a plan, which he directly began to put in execution. He and his wife took up the body, one holding it by the head and the other by the feet; and thus they carried it to the physician’s house. They knocked at the door, at the bottom of a steep and narrow flight of stairs leading to the physician’s apartment. A maid-servant immediately came down without even staying for a light; and, opening the door, she asked them what they wanted. ‘Have the kindness to tell your master,’ said the tailor, ‘that we have brought him a patient who is very ill, and for whom we request his advice.’ Then he held out a piece of money in his hand, saying, ‘Give him this in advance, that he may be assured we do not intend he should give his labour for nothing.’ While the servant went back to inform her master, the Jewish physician, of this good news, the tailor and his wife quickly carried the body of the little hunchback upstairs, placed him close to the door, and returned home as fast as possible.

“In the meantime the servant went and told the physician that a man and a woman were waiting for him at the door, and that they had brought a sick person with them, whom they requested him to see. She then gave him the money she had received from the tailor. Pleased at the thought of being paid beforehand, the physician concluded this must be a most excellent patient, and one who ought not to be neglected. ‘Bring a light directly,’ cried he to the girl, ‘and follow me.’ So saying, he ran towards the staircase in a hurry, without even waiting for the light; and, stumbling against the little hunchback, he gave him such a blow with his foot as sent him from the top of the stairs to the bottom; indeed he had some difficulty to prevent himself from following him. He called out to the servant, bidding her come quickly with the light. She at last appeared, and they went downstairs. When the physician found that it was a dead man who had rolled downstairs, he was so alarmed at the sight that he invoked Moses, Aaron, Joshua, Esdras, and all the other prophets of the law, to his assistance. ‘Wretch that I am!’ exclaimed he, ‘why did I not wait for the light? Why did I go down in the dark? I have completely killed the sick man whom they brought to me. I am the cause of his death! I am a lost man! Alas, alas! they will come and drag me hence as a murderer!’

The hunchback sings to the tailor’s wife.

“Notwithstanding the perplexity he was in, he took the precaution to shut his door, lest any one passing along the street might perchance discover the unfortunate accident of which he believed himself to be the cause. He immediately took up the body, and carried it into the apartment of his wife, who almost fainted when she saw him come in with his fatal load. ‘Alas!’ she cried, ‘we are quite ruined if we cannot find some means of getting rid of this dead man before to-morrow morning. We shall certainly be slain if we keep him till day breaks. What a misfortune! How came you to kill this man?’ ‘Never mind, in this dilemma, how it happened,’ said the Jew; ‘our only business at present is to remedy this dreadful calamity.’

“The physician and his wife then consulted together to devise means to rid themselves of the body during the night. The husband pondered a long time. He could think of no stratagem likely to answer their purpose; but his wife was more fertile in invention, and said, ‘A thought occurs to me. Let us take the corpse up to the terrace of our house, and lower it down the chimney into the warehouse of our neighbour the Mussulman.’

“This Mussulman was one of the sultan’s purveyors; and it was his office to furnish oil, butter, and other articles of a similar kind for the sultan’s household. His warehouse for these things was in his dwelling-house, where the rats and mice used to make great havoc and destruction.

“The Jewish physician approved of his wife’s plan. They took the little hunchback and carried him to the roof of the house; and, after fastening a cord under his arms, they let him gently down the chimney into the purveyor’s apartment. They managed this so cleverly, that he remained standing on his feet against the wall, exactly as if he were alive. As soon as they found they had landed the hunchback, they drew up the cords, and left him standing in the chimney-corner. They then went down from the terrace, and retired to their chamber. Presently the sultan’s purveyor came home. He had just returned from a wedding feast, and he had a lantern in his hand. He was very much surprised when he saw by the light of his lantern a man standing up in the chimney; but, as he was naturally brave and courageous, and thought the intruder was a thief, he seized a large stick, with which he directly ran at the little hunchback. ‘Oh, oh!’ he cried, ‘I thought it was the rats and mice who ate my butter and tallow; and I find you come down the chimney and rob me. I do not think you will ever wish to visit me again.’ Then he attacked the hunchback, and gave him many hard blows. The body at last fell down, with its face on the ground. The purveyor redoubled his blows; but, at length remarking that the person he struck was quite motionless, he stooped to examine his enemy more closely. When he perceived that the man was dead his rage gave place to fear. ‘What have I done, unhappy man that I am!’ he exclaimed. ‘Alas, I have carried my vengeance too far! May Allah have pity upon me, or my life is gone! I wish all the butter and oil were destroyed a thousand times over before they had caused me to commit so great a crime.’ Thus he stood, pale and confounded. He imagined he already saw the officers of justice coming to conduct him to his punishment; and he knew not what to do.

“While the Sultan of Casgar’s purveyor was beating the little hunchback he did not perceive his hump; the instant he noticed it, he poured out a hundred imprecations on it. ‘Oh, you rascal of a hunchback! you dog of deformity! would to Heaven you had robbed me of all my fat and grease before I had found you here! O ye stars which shine in the heavens, ’ he cried, ‘shed your light to lead me out of the imminent danger in which I am!’ Hereupon he took the body of the hunchback upon his shoulders, went out of his chamber, and walked into the street, where he set it upright against a shop; and then he made the best of his way back to his house, without once looking behind him.

“A little before daybreak, a Christian merchant, who was very rich, and who furnished the palace of the sultan with most things which were wanted there, after passing the night in revelry and pleasure, had just come from home on his way to a bath. Although he was much intoxicated, he had still sufficient consciousness to know that the night was far advanced, and that the people would very soon be called to early prayers. Therefore he was making all the haste he could to get to the bath, for fear any Mussulman, on his way to the mosque, should meet him, and order him to prison as a drunkard. He happened to stop at the corner of the street, close to the shop against which the sultan’s purveyor had placed the little hunchback’s body. He pushed against the corpse, which at the very first touch fell directly against the merchant’s back. The latter fancied himself attacked by a robber, and therefore knocked the hunchback down with a blow of his fist on the head. He repeated his blows, and began calling out, ‘Thief! thief!’

“A guard, stationed in that quarter of the city, came directly on hearing his cries; and seeing a Christian beating a Mussulman (for the little hunchback was of our religion), asked him how he dared ill-treat a Mussulman in that manner. ‘He wanted to rob me,’ answered the merchant; ‘and he came up behind me to seize me by my throat.’ ‘You have revenged yourself,’ replied the guard, taking hold of the merchant’s arm and pulling him away, ‘therefore let him go.’ As he said this, he held out his hand to the hunchback to assist him in getting up; but, observing that he was dead, he cried, ‘Is it thus that a Christian has the impudence to assassinate a Mussulman?’ Hereupon he laid hold of the Christian merchant, and carried him before the magistrate of the police, who sent him to prison till the judge had risen and was ready to examine the accused. In the meantime the merchant became completely sober, and the more he reflected upon this adventure the less could he understand how a single blow with the fist could have taken away the life of a man.

“Upon the report of the guard, and after examining the body which they had brought with them, the judge interrogated the Christian merchant, who could not deny the crime imputed to him, although he in fact was not guilty of it. As the little hunchback belonged to the sultan (for he was one of the royal jesters), the judge determined not to put the Christian to death till he had learnt the will of the prince. He went, therefore, to the palace, to give the sultan an account of what had passed. On hearing the whole story, the monarch cried, ‘I have no mercy to show towards a Christian who kills a Mussulman. Go and do your duty.’ The judge of the police accordingly went back and ordered a gibbet to be erected; and then sent criers through the city to make known that a Christian was going to be hanged for having killed a Mussulman.

“At last they took the merchant out of prison, and brought him on foot to the gallows. The executioner had fastened the cord round the merchant’s neck, and was just going to draw him up into the air, when the sultan’s purveyor forced his way through the crowd, and, rushing straight towards the executioner, called out, ‘Stop, stop! It is not he who has committed the murder, but I.’ The judge of the police, who superintended the execution, immediately interrogated the purveyor, who gave him a long and minute account of the manner in which he had killed the little hunchback; and he concluded by saying that he had carried the body to the place where the Christian merchant had found it. ‘You are going,’ added he, ‘to slay an innocent person, for he cannot have killed a man who was not alive. It is enough for me that I have slain a Mussulman; I will not further burden my conscience with the murder of a Christian, an innocent man.’

“When the purveyor of the Sultan of Casgar thus publicly accused himself of having killed the hunchback, the judge could not do otherwise than immediately release the merchant. ‘Let the Christian merchant go,’ said he to the executioner, ‘and hang in his stead this man, by whose own confession it is evident that he is the guilty person.’ The executioner immediately unbound the merchant, and put the rope round the neck of the purveyor; but at the very instant when he was going to put this new victim to death, he heard the voice of the Jewish physician, who exclaimed that the execution must be stopped, that he himself might come and take his place at the foot of the gallows.

“ ‘Sir,’ said he, directly he appeared before the judge, ‘this Mussulman whom you are about to deprive of life does not deserve to die; I alone am the unhappy culprit. About the middle of last night, a man and a woman, who are total strangers to me, came and knocked at my door. They brought with them a sick person: my servant went instantly to the door without waiting for a light, and, having first received a piece of money from one of the visitors, she came to me and said that they wished I would come down and look at the sick person. While she was bringing me this message they brought the patient to the top of the stairs, and went their way. I went out directly, without waiting till my servant had lighted a candle; and falling over the sick man in the dark, I gave him an unintentional kick, and he fell from the top of the staircase to the bottom. I then discovered that he was dead. He was a Mussulman, the very same little hunchback whose murderer you now wish to punish. My wife and myself took the body, and carried it to the roof of our house, whence we let it down into the warehouse of our neighbour the purveyor, whose life you are now going to take away most unjustly, as we were the persons who placed the body in his house by lowering it down the chimney. When the purveyor discovered the hunchback, he took him for a thief, and treated him as such. He knocked him down, and believed he had killed him; but this is not the fact, as you will have understood by my confession. I alone am the perpetrator of the murder; and, although it was unintentional, I am resolved to expiate my crime, rather than burden my conscience with the death of two Mussulmen, by suffering you to take away the life of the sultan’s purveyor. Therefore dismiss him, and let me take his place; for I alone have been the cause of the hunchback’s death.’

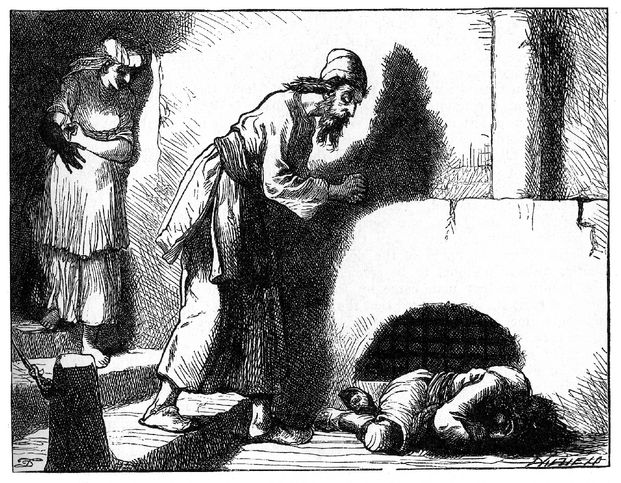

The hunchback found by the Jewish physician.

“Convinced that the Jewish physician was the true murderer, the judge now ordered the executioner to seize him, and set the purveyor at liberty. The cord was placed round the neck of the physician, and in another moment he would have been a dead man, when the voice of the tailor was heard entreating the executioner to stop; and presently the tailor pushed his way to the judge of the police, to whom he said, ‘You have very nearly caused the death of three innocent persons; but if you will have the patience to listen to me, you shall hear who was the real murderer of the hunchback. If his death is to expiated by that of another person, I am the person who ought to die.

“ ‘As I was at work in my shop yesterday evening, a little before dark, feeling in a merry humour, this little hunchback came to my door half tipsy, and sat down. He immediately began to sing, and had been doing so for some time, when I proposed to him to come and pass the evening at my house. He agreed to my proposal; and I took him home with me. We sat down to table almost directly, and I gave him a little piece of fish. While he was eating it a bone stuck fast in his throat, and, in spite of everything that my wife and I could do to relieve him, he died in a very short time. We were grieved and alarmed at his death; and for fear of being called to account for it, we carried the body to the door of the Jewish physician. I knocked, and told the servant who let me in to go back to her master as soon as possible, and request him to come down to see a patient whom we had brought to him; and that he might not refuse I charged her to put into his own hand a piece of money which I gave her. Directly she had gone I carried the little hunchback to the top of the stairs, and laid him on the first step, and leaving him there my wife and myself made the best of our way home. When the physician came out of his room to go downstairs he stumbled against the hunchback, and rolled him down from the top to the bottom; this made him suppose that he was the cause of the little man’s death. But seeing how the case stands, let the physician go, and take my life instead of his.’

“The judge of the police and all the spectators were filled with astonishment at the various strange events to which the death of the little hunchback had given rise. ‘Let the physician then depart,’ said the judge, ‘and hang the tailor, since he confesses the crime. I most candidly own that this adventure is very extraordinary, and worthy of being written in letters of gold.’ When the executioner had set the physician at liberty, he put the cord round the tailor’s neck.

“While all this was going on, and the executioner was preparing to hang the tailor, the Sultan of Casgar, who never allowed any length of time to pass without seeing the little hunchback his jester, ordered that he should he summoned into his presence. One of the attendants replied, ‘The little hunchback whom your majesty is so desirous to see yesterday became tipsy, and escaped from the palace, contrary to his usual custom, to wander about the city; and this morning he was found dead. A man has been brought before the judge of the police, accused of his murder, and the judge immediately ordered a gibbet to be erected. At the very moment they were going to hang the culprit another man came up to the gallows, and then a third. Each of these accused himself, and declared that the rest were innocent of the murder. All this took up some time, and the judge is at this moment in the very act of examining the third of these men, who says he is the real murderer.’

“On hearing this report the Sultan of Casgar sent one of his attendants to the place of execution. ‘Go,’ he cried, ‘with all possible speed, and command the judge to bring all the accused persons instantly before me, and order them also to bring the body of the poor little hunchback, whom I wish to see once more.’ The officer instantly went, and arrived at the very moment when the executioner was beginning to draw the cord, in order to hang the tailor. The messenger called out to them as loud as he could to suspend the execution. As the hangman knew the officer, he dared not proceed, so he desisted from hanging the tailor. The officer now came up to the judge and declared the will of the sultan. The judge obeyed, and proceeded to the palace with the tailor, the Jew, the purveyor, and the Christian merchant; and ordered four of his people to carry the body of the hunchback.

“As soon as they came into the presence of the sultan, the judge prostrated himself at the monarch’s feet; and when he rose he gave a faithful and accurate detail of everything that related to the adventure of the little hunchback. The sultan thought it so very singular that he commanded his own historian to write it down, with all its particulars; then, addressing himself to those who were present, he said, ‘Has any one of you ever heard a more wonderful adventure than this which has happened to the hunchback my jester?’ The Christian merchant prostrated himself so low at the sultan’s feet that his head touched the ground; then he spoke as follows: ‘Powerful monarch, I think I know a history still more surprising than that which you have just heard, and if your majesty will grant me permission I will relate it. The circumstances are so wonderful that no person can hear them without being affected at the narrative.’ The sultan gave the merchant permission to speak; and the latter began his story in these words:—