THE STORY TOLD BY THE PURVEYOR OF THE SULTAN OF CASGAR.

I WAS yesterday, great monarch, invited by a man of great position and fortune to the wedding of one of his daughters. I did not fail to be at his house by the appointed hour; and found a large company of the best inhabitants of the city. When the ceremony was over, the feast, which was very magnificent, was served up. We sat down to table, and each person ate what was most agreeable to his taste. There was one dish dressed with garlic, which was so very excellent that every one wished to try it. We remarked, however, that one of the guests avoided eating any, although the dish stood directly before him. We invited him to help himself to some, as we did; but he requested us not to press him to touch it. ‘I shall be very careful,’ said he, ‘how I touch a ragout dressed with garlic. I have not yet forgotten the consequences to me the last time I tasted one.’ We inquired the cause of the aversion he seemed to have to garlic; but the master of the house called out, without giving him time to answer our inquiries, ‘Is it thus you honour my table? This ragout is delicious. Do not, therefore, refuse to eat of it; you must do me that favour, like the rest of the company.’ ‘My master,’ replied his guest, who was a merchant of Baghdad, ‘I certainly will obey your commands if you insist; but it must only be on condition that, after eating the ragout of garlic, you will permit me to wash my hands forty times with alkali, forty times with the ashes of the plant from which that substance is procured, and as many times with soap. I hope you will not be offended at this design of mine, for it is in consequence of an oath I have taken, and which I must not break, never to eat a ragout

m with garlic without observing these ceremonies!’

“As the master of the house would not excuse the merchant from eating some of the ragout, he ordered his servants to get ready some basins, containing a solution of alkali, ashes of the same plant, and soap, that the merchant might wash as often as he pleased. After giving these orders, he said to the merchant, ‘Come, now, do as we do, and eat; neither the alkali, the ashes of the plant, nor the soap shall be wanting.’

“Although the merchant was angry at the sort of compulsion to which he was subjected, he put out his hand, and took a small quantity of the ragout, which he put to his mouth with fear and trembling, and ate with a repugnance that very much astonished us all. But we remarked with still greater surprise that he had only four fingers, and no thumb. No one had noticed this circumstance until now, although he had eaten of several other dishes. The master of the house then said, ‘You seem to have lost your thumb; how did such an accident happen? There must have been some singular circumstances connected with it; and you will afford this company great pleasure if you will relate them.’

“ ‘It is not only on my right hand that I have no thumb,’ replied the guest; ‘my left is also in the same state.’ He held out his left hand as he spoke, that we might be convinced he told the truth. ‘Nor is this all,’ he added; ‘I have lost the great toe from each of my feet. I have been maimed in this manner through a most extraordinary adventure, which I have no objection to relate if you will have the patience to listen to it; and I think it will not excite your compassion equally with your astonishment. First of all, however, permit me to wash my hands.’ So saying, he rose from table; and after washing his hands one hundred and twenty times, he sat down again, and related the following story:—

“ ‘You must know, my masters, that my father lived at Baghdad, where I also was born, during the reign of the Caliph Haroun Alraschid, and he was reckoned one of the richest merchants in that city. But as he was a man much addicted to pleasure and dissipation, he very much neglected his affairs; instead, therefore, of inheriting a large fortune at his death, I found myself greatly embarrassed, and was obliged to use the greatest economy to pay the debts he left behind him. By dint of great attention and care, however, I at last discharged them all, and my small fortune then began to assume a favourable appearance.

“ ‘One morning, as I was opening my shop, a lady, mounted upon a mule, accompanied by an eunuch, and followed by two slaves, came riding towards my warehouse, and stopped in front of my door. The eunuch directly assisted her to alight; he then said to her, ‘I am afraid, lady, you have arrived too soon; you see, there is no one yet come to the bazaar. If you had believed what I said, you would not have had the trouble of waiting. ’ She looked round on every side, and finding that there was, in fact, no other shop open but mine, she came up, and saluting me, requested permission to sit down till the other merchants arrived. I replied civilly that my shop was at her service.

“ ‘The lady entered my shop and sat down; and as she observed there was no one to be seen in the bazaar except the eunuch and myself, she took off her veil in order to enjoy the air. I had never seen any one so beautiful, and to gaze upon her and to be passionately in love were with me one and the same thing. I kept my eyes constantly fixed upon her, and I thought she looked as if my admiration was not unpleasing to her; for she gave me full opportunity of beholding her during the whole time of her stay, nor did she put down her veil till the fear of the approach of strangers obliged her to do so. After she had adjusted her veil, she informed me that she had come with the intention of looking at some of the finest and richest kinds of stuff, which she described to me, and inquired whether I had any such wares. ‘Alas! lady,’ I said, ‘I am but a young merchant, and have not long begun business; I am not yet rich enough to trade so largely; and it is a great mortification to me that I have none of the things for which you came into the bazaar; but to save you the trouble of going from shop to shop, let me, as soon as the merchants come, go and get from them whatever you wish to see. They will tell me exactly the lowest price, and you will thus be enabled, without having the trouble of seeking farther, to procure all you require.’ To this she consented, and I began a conversation with her which lasted a long time, as I made her believe that those merchants who had the stuffs she wanted were not yet come.

“ ‘I was not less delighted with her wit and understanding than I had been with her personal charms. I was, however, at last compelled to deprive myself of the pleasure of her conversation, and I went to seek the stuffs she wanted. When she had decided upon those she wished to have, I informed her that they came to five thousand drachms of silver. I then made them up into a parcel, and gave them to the eunuch, who put them under his arm. The lady immediately rose, took leave of me, and went away. I followed her with my eyes until she had reached the gate of the bazaar, nor did I cease to gaze at her till she had mounted her mule.

“ ‘When the lady was out of sight, I recollected that my love had caused me to be guilty of a great fault. My beautiful visitor had so wholly engrossed my attention that I had not only omitted taking the money for the goods, but even neglected to inquire who she was, and where she lived. This led me immediately to reflect that I was accountable for a very large sum of money to several merchants, who would not, perhaps, have the patience to wait. I then went and excused myself to them in the best way I could, telling them I knew the lady very well. I returned home as much in love as ever, although very much depressed at the idea of the heavy debt I had incurred.

“ ‘I requested my creditors to wait a week for their money, which they agreed to do. On the eighth morning they did not fail to come and demand payment; but I again begged the favour of a little further delay, and they kindly granted my request; but on the very next morning I saw the lady coming along on the same mule, with the same persons attending her, and exactly at the same hour as at her first visit.

“ ‘She came directly to my shop. She said, ‘I have made you wait a little for your money in payment for the stuffs which I had the other day, but I have at last brought it you. Go with it to a money-changer, and see that it is all good, and that the sum is right.’ The eunuch who had the money went with me to a money-changer. The sum was exactly correct, and all good silver. After this I had the happiness of a long conversation with the lady, who stayed till all the shops in the bazaar were open. Although we conversed only upon common topics, she gave a certain grace and novelty to the whole discourse, and confirmed me in my first impression, that she possessed much wit and good sense.

“ ‘As soon as the merchants were come and had opened their shops, I took the sum I owed to each of those from whom I had purchased the stuffs on credit; and I had now no difficulty in getting from them other pieces which the lady had desired to see. I carried back with me brocades worth a thousand pieces of gold, all of which she took away with her; and not only did she omit to pay for them, but never mentioned the subject, or even informed me who she was or where she lived. What puzzled me the most was that she ran no risk and hazarded nothing, while I remained without the least security, and without any chance of being indemnified in case I should not see her again. I said to myself, ‘She has certainly paid me a very large sum of money, but she has left me responsible for a debt of much greater amount. Is it possible she can intend to cheat me, and thus, by paying me for the first quantity, has only enticed me to more certain ruin? The merchants themselves do not know her, and depend only upon me for payment.’

“ ‘My love was not powerful enough to prevent me from making these distressing reflections for one entire month. My fears kept increasing from day to day, and time passed on without my having any intelligence whatever of the lady. The merchants at last began to grow very impatient, and in order to satisfy them I was going to sell off everything I had; when, one morning, I saw the lady coming with exactly the same attendants as before. ‘Take your weights,’ she said to me, ‘and weigh the gold I have brought you.’ These few words put an end to all my fears, and my regard for her was greater than ever.

“ ‘Before she began to count out the gold, she asked me several questions; and among the rest inquired if I was married. I told her I was not, nor had I ever been. Thereupon she gave the gold to the eunuch, and said to him: ‘Come, let us have your assistance to settle our affairs.’ The eunuch could not help smiling; and taking me aside he made me weigh the gold.

“ ‘While I was thus employed, the eunuch whispered the following words in my ear:—‘I have only to look at you to see that you are desperately in love with my mistress; and I am surprised that you have not the courage to declare your passion to her. She loves you, if possible, more than you love her. Don’t suppose that she wants any of your stuffs; she only comes here out of affection for you; and this was the reason why she asked you whether you were married. You have only to declare yourself, and if you wish it, she will not hesitate even to marry you.’ ‘It is true,’ I replied, ‘that I felt emotions of love arise in my breast the very first moment I beheld your lady; but I never thought of aspiring to the hope of having pleased her. I am wholly her own, and shall not fail to remember the good service you have done me.’

“ ‘When I had finished weighing the gold, and while I was putting it back into the bag, the eunuch went to the lady, and said that I was very well satisfied. This was the expression they had agreed upon between themselves. The lady, who was seated, immediately rose and went away, telling me first that she would send back the eunuch, and that I must do exactly as he directed.

“ ‘I then went to all the merchants to whom I was indebted, and paid them. After this I waited with the greatest impatience for the arrival of the eunuch; but it was some days before he made his appearance. At length he appeared.

“ ‘I received him in the most kind and friendly manner, and made many inquiries after the health of his mistress. He replied: ‘You are certainly the happiest lover in all the world: she is absolutely dying for love of you. It is impossible you can be more anxious to see her than she is for

The favourite visiting the merchant of Baghdad.

your company; and if she were able to follow her own inclinations, she would instantly come to you, and gladly pass every moment of her future life with you.’ ‘From her noble air and manner,’ I replied, ‘I have concluded she is a lady of great rank and consequence.’ ‘Your opinion is quite correct,’ said the eunuch; ‘she is the favourite of Zobeidè, the sultana, who is strongly attached to her, and has brought her up from her earliest infancy; and Zobeidè’s confidence in her is so great that she employs her in every commission she wishes to have executed. Inspired with affection for you, she has told her mistress Zobeidè that she has cast her eyes upon you, and has asked the sultaness to consent to the match. Zobeidè has listened favourably, but has requested in the first instance to see you, that she may judge whether her favourite has made a good choice; and in case she approves of you, she will herself bear the expenses of the wedding. Know, therefore, that your happiness is certain. As you have pleased the favourite you will please her mistress, whose sole wish is to be kind to her attendant, and who has not the least desire of putting any restraint upon the lady’s inclination. The only thing, therefore, you have to do is to go to the palace; and this was the reason of my coming here. You must now tell me what you determine to do.’ ‘My resolution is already taken,’ I replied; ‘and I am ready to follow you when and where you choose to conduct me.’ ‘That is well,’ said the eunuch; ‘but you must recollect that no man is permitted to enter the apartments belonging to the ladies in the palace, and that you can be introduced there only by such means as will keep your presence a profound secret. The favourite has thought of a scheme by which she may effect this; and you must on your part do everything to facilitate it. But above all things you must be discreet, or your life may be the forfeit.’

“ ‘I assured him that I would obey his directions exactly. ‘You must then,’ he said, ‘go this evening to the mosque which the lady Zobeidè has caused to be built on the banks of the Tigris; and you must wait there till we come to you.’ I agreed to do everything he wished, and waited with the greatest impatience till the day was gone. When the evening fell, I set out and went to prayers, which began an hour and a half before sunset, at the appointed mosque, and remained there till every one else had left.

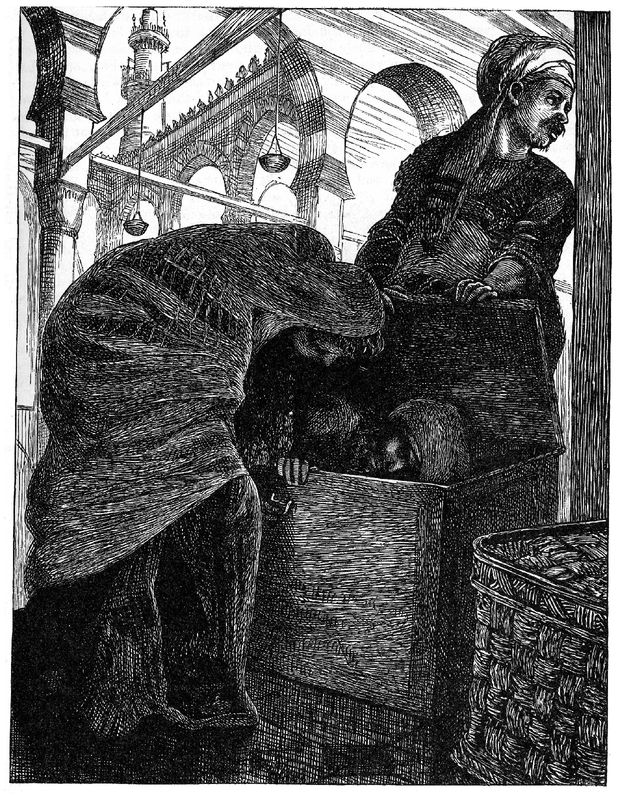

“ ‘Almost immediately after prayers I saw a boat come to shore, rowed by eunuchs. They landed and brought a great number of chests into the mosque. Hereupon they all went away except one, whom I soon recognised as the man who had accompanied the lady, and who had spoken with me that very morning. Presently I saw the lady herself come in. I went up to her, and was explaining to her that I was ready to obey all her orders, when she said, ‘We have no time to lose in conversation.’ She opened one of the chests and ordered me to get in, adding, ‘It is absolutely necessary both for your safety and mine. Fear nothing, and leave me to manage this affair.’ I had gone too far to recede; therefore I did as she desired, and she immediately shut down the top of the chest, and locked it. The eunuch who was in her confidence then called the other eunuchs who had brought the chests, and ordered them to carry the boxes back on board the boat. The lady and the eunuch then embarked, and they began to row toward the apartments of Zobeidè.

“ ‘As I lay in the chest I had leisure to make the most serious reflections; and I repented most heartily of having exposed myself to the danger I was in. I gave vent to alternate prayers and regrets; but both were now useless and out of season.

“ ‘The boat came ashore exactly before the gate of the caliph’s palace. The chests were all landed and carried to the apartment of the officer of the eunuchs, who keeps the key of the ladies’ dwelling, and who never permits anything to be carried in without first examining it. The officer had gone to bed; it was therefore necessary to wake him and make him get up. He was greatly out of humour at having his rest thus disturbed. He quarrelled with the favourite because she returned so late. ‘You shall not finish your business so soon as you think,’ said he to her, ‘for not one of these chests shall pass till I have opened and examined them narrowly.’ Accordingly he commanded the eunuchs to bring them to him one after the other, that he might open them. They began by taking the very chest in which I was shut up, and set it down before him. At this I was more terrified than I can express, and thought the last moment of my life was approaching.

“ ‘The favourite, who had the key, declared she would not give it him, nor suffer that chest to be opened. ‘You know very well,’ she said, ‘that I do not bring anything in here but what is ordered by our mistress Zobeidè. This chest is filled with very valuable articles that have been entrusted to me by some merchants who have just arrived. There are also a great many bottles of water from the fountains of Zemzem at Mecca; and if one of these comes to be broken all the other things will be spoiled, and you will be answerable for them. The wife of the Commander of the Faithful will know how to punish your insolence.’ She said this in so peremptory a tone, that the officer had not courage to persist in his resolution of opening the chest in which I was, or any of the others. ‘Begone, then!’ he angrily cried: ‘go!’ The door of the ladies’ apartment was immediately opened, and the chests were all carried in.

“ ‘Scarcely had they been placed on the ground, when I suddenly heard the cry of ‘The caliph! the caliph is coming!’ These words increased my fears to such a degree that I was almost ready to die on the spot. Presently the caliph came in. ‘What have you there in those chests?’ said he to the favourite. ‘Commander of the Faithful,’ she replied, ‘they are some stuffs lately arrived, which Zobeidè my mistress wished to inspect.’ ‘Open them,’ said he, ‘and let me see them also.’ She endeavoured to excuse herself by saying they were only fit for females, and that Zobeidè would not like to be deprived of the pleasure of seeing them before any one else. ‘Open them, I tell you,’ he answered; ‘I command you!’ She still remonstrated, alleging that the sultaness would be very angry if she did as his majesty ordered. ‘No, no,’ replied the caliph, ‘I will promise you that she shall not be angry. Only open them, and do not detain me longer.’

“ ‘It was then absolutely necessary that the favourite should obey. My fears were again excited; and I tremble, even now, every time I think of that dreadful moment. The caliph seated himself, and the favourite ordering all the chests to be brought, opened them one after the other, and displayed the stuffs before him. To prolong the business as much as possible, she pointed out to him the peculiar beauties of each individual stuff, in the hope that she might tire out his patience; but she did not succeed. At last all the chests had been inspected except the one in which I lay. ‘Come,’ said the caliph, ‘let us make haste and finish this business; we have now only to see what is in yonder chest.’ On hearing these words, I knew not whether I was alive or dead; for I now lost all hope of escaping the terrible danger I was in.

“ ‘When the favourite saw that the caliph was determined she should open the chest in which I was concealed, she said, ‘Your majesty must be content. There are some things in that chest which I cannot show, except in the presence of the sultana my mistress.’ ‘Be it so,’ replied the caliph, ‘I am content: let them carry the chests in.’ The eunuchs immediately took them up, and placed them in Zobeidè’s chamber, where I again began to breathe freely.

“ ‘As soon as the eunuchs who brought in the chests retired, the favourite quickly opened that in which I was a prisoner. ‘Come out,’ she cried; and, showing me a staircase which led to a chamber above, she added, ‘Go up, and wait for me there.’ She had hardly shut the door after me when the caliph came in, and sat down upon the very chest in which I had been locked up. The motive of this visit was a fit of curiosity, which did not in the least relate to me. The caliph only wished to ask the favourite some questions as to what she had seen and heard in the city. They conversed a long time together: at last he left her, and went back to his own apartment.

“ ‘So soon as she was at liberty she came into the apartment in which I waited, and made a thousand excuses for the alarm I had suffered. ‘My anxiety and fear,’ she said, ‘quite equalled your own. This you ought not to doubt, since I suffered both for you, from my great regard for you, and for myself, on account of the great danger I ran. I think few persons in my position would have had the address and courage to extricate themselves from so delicate a situation. It required equal boldness and presence of mind, or rather all the love I felt for you was required to sharpen my wits in that terrible dilemma, to get out of such an embarrassment. But compose yourself now: there is nothing more to fear.’ After we had gratified ourselves some time with mutual avowals of our affection, she said, ‘You want repose; you are to sleep here, and I will not fail to present you to my mistress Zobeidè some time to-morrow. This is a very easy matter, as the caliph will be absent.’ Encouraged by this account, I slept with the greatest tranquillity. If my rest was at all interrupted, it was by the pleasant ideas that arose in my mind from the thought that I should soon marry a lady of remarkable understanding and beauty.

“ ‘The next morning, before the favourite of Zobeidè introduced me to her mistress, she instructed me how I should behave in her presence. She informed me almost word for word what Zobeidè would ask me, and dictated appropriate answers. She then led me into a hall, where everything was very magnificent, very rich, and very well chosen. I had not been long there when twenty female slaves, all dressed in rich and uniform habits, came out from the cabinet of Zobeidè, and immediately ranged themselves before the throne in two even rows with the greatest modesty and propriety. They were followed by twenty other female slaves, very young, and dressed exactly like the first, with this difference only, that their dresses were much more splendid. Zobeidè, a lady of very majestic aspect, appeared in the midst of the young slaves. She was so loaded with precious stones and jewels that she could scarcely walk. She went immediately and seated herself upon the throne. I must not forget to mention that her favourite lady accompanied her, and remained standing close on her right hand, while the female slaves were grouped altogether at a little distance on both sides of the throne.

“ ‘As soon as the caliph’s consort was seated, the slaves who came in first made a sign for me to approach. I advanced between two ranks, which they formed for that purpose, and prostrated myself till my head touched the carpet which was under the feet of the princess. She ordered me to rise, and honoured me so far as to ask my name, and to inquire concerning my family and the state of my fortune. In my answers to all these questions I gave her perfect satisfaction. I was confident of this, not only from her manner, but from a thousand kind things she had the condescension to say to me. ‘I have great satisfaction,’ said she, ‘in finding that my daughter (for as such I shall ever regard her, after the care I have taken of her education) has made such a choice. I entirely approve of it, and agree to your marriage. I will myself give orders for the necessary preparations. But for the next ten days before the ceremony can take place I shall require my daughter’s services; and during this time I will take an opportunity of speaking to the caliph, and obtaining his consent; meanwhile you shall remain here, and shall be well taken care of.’

“ ‘I spent these ten days in the ladies’ apartments; and during the whole time I was deprived of the pleasure of seeing the favourite, even for one moment; but, by her direction, I was so well treated that I had great reason to be satisfied in every other respect.

“ ‘Zobeidè in the meantime informed the caliph of the determination she had taken to give her favourite in marriage; and the caliph not only left her at liberty to act as she pleased in this matter, but even gave a large sum of money to the favourite as his contribution towards setting up her establishment. The appointed time at length came, and Zobeidè had a proper contract of marriage prepared, with all the necessary forms, Preparations for the nuptials were made; musicians and dancers of both sexes were ordered to hold themselves in readiness; and for nine days the greatest joy and festivity reigned through the palace; the tenth was the day appointed for the concluding ceremony of the marriage. The favourite was led to a bath on one side, and I proceeded to one situate on the other. In the evening I sat down to table, and the attendants served me with all sorts of dishes and ragouts. Among other things, there was a ragout made with garlic, similar to the dish of which you have now forced me to eat. I found it so excellent that I hardly touched any other food. But, unfortunately for me, when I rose from table I only wiped my hands, instead of well washing them. This was a piece of negligence of which I believe I had never before been guilty.

“ ‘As it was now night, a grand illumination was made in all the ladies’ apartments. The sweet tones of instruments of music resounded through the building. The guests danced, they joined in a thousand sports, and the palace re-echoed with exclamations of joy and pleasure. My bride and I were led into a large hall, and seated upon two thrones. The maidens who attended on the bride changed her dress several times, according to the general practice on these occasions. Every time they thus changed her dress they presented her to me.

The favourite locks the merchant in the box.

“ ‘When all these ceremonies were finished, I approached my bride to embrace her. But she forcibly repulsed me, and called out in the most lamentable and violent manner; so much so, that the women all rushed towards her, desirous of learning the reason of her screams. As for myself, my astonishment was so great that I stood quite motion less, without having even power to ask the cause of this strange behaviour. ‘What can possibly have happened to you?’ the women said to my bride: ‘inform us, that we may help you.’ Then she cried: ‘Take away, instantly take from my sight, that infamous man!’ ‘Alas! madam,’ I exclaimed, ‘how can I possibly have incurred your anger?’ ‘You are a villain,’ said she, in the greatest rage. ‘You have eaten garlic, and have not washed your hands. Do you think I will suffer a man who can be guilty of so dirty and so filthy a negligence to approach me? Lay him on the ground,’ she added, speaking to the women, ‘and bring me a whip.’ They immediately threw me down; and while some held me by the arms, and others by the feet, my wife, who had been very quickly obeyed, beat me without the least mercy as long as she had any strength. She then said to the females, ‘Take him before an officer of the police, and let him have that hand cut off with which he fed himself with the garlic ragout.’

“ ‘At these words I exclaimed, ‘Merciful Allah! I have been abused and whipped, and to complete my misfortune I am to be still further punished by having my hand cut off! And all for what? Because, forsooth, I have eaten of a ragout made with garlic, and have forgotten to wash my hands! What a trifling cause for such anger and revenge! Curses on the garlic ragout! I wish that the cook who made it, and the slave who served it up, were at the bottom of the sea!’

“ ‘But now every one of the women present, who had seen me already so severely punished, pitied me very much when they heard the favourite talk of having my hand cut off. ‘My dear sister and my good lady,’ said they to her, ‘do not carry your resentment so far. It is true that he is a man who does not appear to know how to conduct himself, and who seems not to understand your rank, and the respect that is due to you. We entreat you, however, not to take further notice of the fault he has committed, but to pardon him.’ ‘I am not yet satisfied,’ she cried; ‘I wish to teach him how to behave, and require that he should bear such lasting marks of his ill breeding, that he will never forget, so long as he lives, having eaten garlic without remembering to wash his hands after it.’ They were not discouraged by this refusal. They threw themselves at her feet, and kissing her hand, cried, ‘My good lady, in the name of Allah, moderate your anger, and grant us the favour we ask of you.’ She did not answer them a single word; but got up, and, after abusing me again, went out of the apartment. All the women followed her, and left me quite alone in the greatest possible affliction.

“ ‘I remained here ten days, seeing no one except an old slave who brought me some food. I asked her for some information concerning my bride. ‘She is very ill,’ she said, ‘from grief at your usage of her. Why did you not take care to wash your hands after eating of that diabolical ragout?’ ‘Is it possible, then,’ I answered, ‘that these ladies are so dainty? and that they can be so vindictive for so slight a fault?’ But I still loved my wife, in spite of her cruelty, and could not help pitying her.

“ ‘One day the old slave said to me, ‘Your bride is cured: she is gone to the bath; and she told me that she intended to come and visit you to morrow. Therefore have a little patience, and endeavour to accommodate yourself to her humour. She is very just and very reasonable; and is moreover very much beloved by all the women in the service of Zobeidè our royal mistress.’

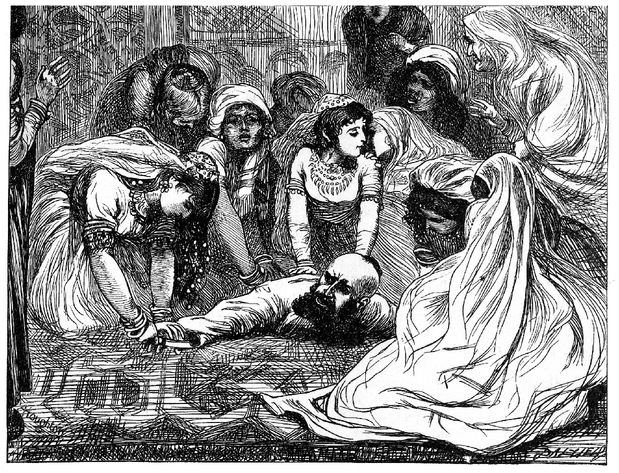

“ ‘My wife really came to see me the next day; and she immediately said to me: ‘You must think me very good to come and see you again, after the offence you have given me; but I cannot bring myself to be reconciled to you till I have punished you as you deserve for not washing your hands after having eaten the ragout with garlic.’ When she had said this she called to the women, who instantly entered, and laid me down upon the ground according to her orders; and after they had bound me, she took a razor, and had the barbarity with her own hands to cut off my two thumbs and two great toes. One of the women immediately applied a certain root to stop the bleeding; but this did not prevent me from fainting, partly from loss of blood, and partly from the great pain I suffered.

“ ‘When I had recovered from my fainting fit, they gave me some wine, to recruit my strength and spirits. ‘Ah! Lady,’ I then said to my wife, ‘if it should ever fall to my lot again to partake of a ragout with garlic, I swear to you that instead of washing my hands once, I will wash them one hundred and twenty times; with alkali, with the ashes of the plant from which alkali is made, and with soap.’ ‘Then,’ replied my wife, ‘on this condition I will forget what has passed, and live with you as your wife.’

“ ‘This is the reason,’ continued the merchant of Baghdad, addressing himself to all the company, ‘why I refused to eat of the garlic ragout which was served up just now.

“ ‘The women not only applied the root to my wounds, as I have told you, to stop the blood, but they also put some balsam of Mecca to them, which was certainly unadulterated, since it came from the caliph’s own store. By the virtue of this excellent balsam I was perfectly cured in a very few days. After this, my wife and I lived together as happily as if I had never tasted the garlic ragout. Still, as I had always been in the habit of enjoying my liberty, I began to grow very weary of being constantly shut up in the palace of the caliph; but I did not give my wife any reason to suspect that this was the case, for fear of displeasing her. At last, however, she perceived it; and, indeed, she wished as anxiously as I did to leave the palace. Gratitude alone attached her to Zobeidè. But she possessed both courage and ingenuity; and she so well represented to her mistress the constraint I felt myself under, in not being able to live in the city and associate with men of my own position, as I had always been accustomed to do, that the excellent princess preferred to deprive herself of the pleasure of having her favourite near her rather than refuse her request.

“ ‘Thus it happened, that about a month after our marriage I one day perceived my wife come in, followed by many eunuchs, each of whom carried a bag of money. When they had withdrawn, my wife said to me, ‘You have not complained to me of the uneasiness and languor which your long residence in the palace has caused you; but I have nevertheless perceived it, and I have fortunately found out a method to put you at your ease. My mistress Zobeidè has permitted us to leave the palace; and here are fifty thousand sequins, which she has given us, that we may live comfortably and commodiously in the city. Take ten thousand, and go and purchase a house.’

The favourite cuts off her husband’s thumbs.

“ ‘I very soon bought one for that sum; and, after furnishing it most magnificently, we went to live there. We took with us a great number of slaves of both sexes, and we dressed them in the handsomest manner possible. In short, we began to live the most pleasant kind of life; but, alas! it was not of long duration. At the end of a year my wife fell sick; and in a few days she died.

“ ‘I should certainly have married again, and continued to live in the most honourable manner at Baghdad; but the desire I felt to see the world put other thoughts in my head. I sold my house; and, after purchasing different sorts of merchandise, I attached myself to a caravan, and travelled into Persia. From thence I took the road to Samarcand, and at last came and established myself in this city.’

“ ‘This, O king!’ said the purveyor to the Sultan of Casgar, ‘is the history which the merchant of Baghdad related to the company at the house where I was yesterday.’

‘Truly, it comprises some very extraordinary details,’ replied the sultan; ‘but yet it is not to be compared to the story of my little hunchback.’ The Jewish physician then advanced, and prostrated himself before the throne of the sultan; and, on rising, said to him, ‘If your majesty will have the goodness to listen to me, I flatter myself that you will be very well satisfied with the history I shall have the honour to relate.’ ‘Speak,’ said the sultan; ‘but if thy story be not more wonderful than that of the hunchback, do not hope I shall suffer thee to live.’ ”