THE HISTORY OF THE BARBER’S SIXTH BROTHER.

THE history of my sixth brother is the only one that now remains to be told. He was called Schacabac, the Hare-lipped. He was at first sufficiently industrious to employ the hundred drachms of silver which came to his share in a very advantageous manner; but at length he was reduced, by reverse of fortune, to the necessity of begging his bread. In this occupation he acquitted himself with great address; and his chief aim was to procure admission into the houses of the great, by bribing the officers and domestics; and when he had once managed to get admitted to them, he failed not to excite their compassion.

“He one day passed by a very magnificent building, through the door of which he could see a spacious court, wherein were a vast number of servants. He went up to one of them, and inquired of them to whom the house belonged. ‘My good man,’ answered the servant, ‘where can you come from, that you ask such a question? Any one you met would tell you it belonged to a Barmecide.’ My brother, who well knew the liberal and generous disposition of the Barmecides, addressed himself to the porters, for there were more than one, and requested them to bestow some charity upon him. ‘Come in,’ answered they, ‘no one prevents you, and speak to our master—he will send you back well satisfied.’

“My brother did not expect so much kindness; and after returning many thanks to the porters, he with their permission entered the palace, which was so large that he spent some time in seeking out the apartment belonging to the Barmecide. He at length came to a large square building very handsome to behold, into which he entered by a vestibule that led to a fine garden, the walks of which were formed of stones of different colours, with a very pleasing effect to the eye. The apartments which surrounded this building on the ground floor were almost all open, and shaded only by some large curtains which kept off the sun, and which could be drawn aside to admit the fresh air when the heat began to subside.

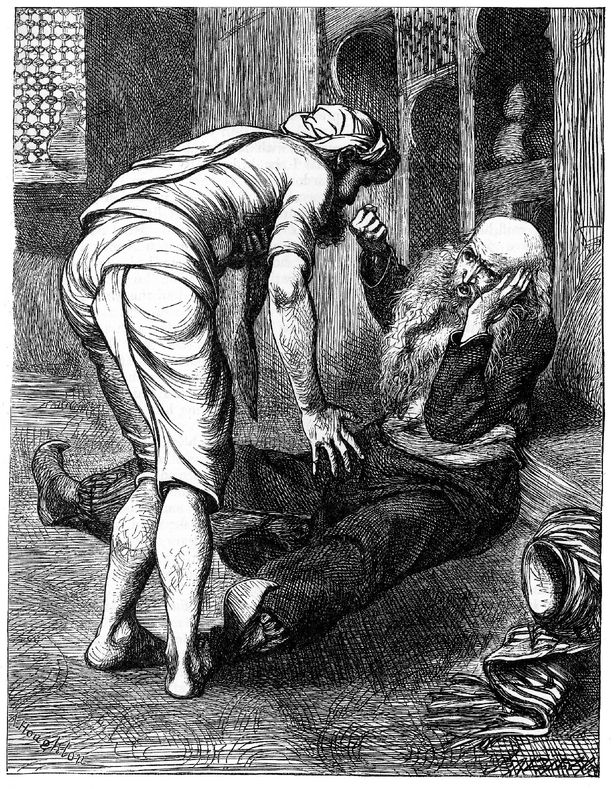

“My brother would have been highly delighted with this pleasant spot had his mind been sufficiently at ease to enjoy its beauties. He advanced still farther, and entered a hall, which was very richly furnished, and ornamented with foliage painted in azure and gold. He perceived a venerable old man, whose beard was long and white, sitting on a sofa in the most distinguished place. He judged that this was the master of the house. In fact, it was the Barmecide himself, who told him in an obliging manner that he was welcome, and asked him what he wished. ‘My lord,’ answered my brother, in a lamentable tone, ‘I am a poor man, who stands very much in need of the assistance of such powerful and generous persons as yourself.’ He could not have done better than address himself to the person to whom he spoke, for this man possessed a thousand amiable qualities.

“The Barmecide was much astonished at my brother’s answer; and putting both his hands to his breast, as if to tear his clothes, as a mark of commiseration, he exclaimed: ‘Is it possible that in Baghdad such a man as you should be so much distressed as you say you are? I cannot suffer this to be.’ At this exclamation my brother, thinking the Barmecide was going to give him a singular proof of his liberality, wished him every blessing. ‘It shall never be said,’ replied the Barmecide, ‘that I leave you un-succoured. I intend that you shall not leave me.’ ‘O my master,’ cried my brother, ‘I swear to you that I have not even eaten anything this day.’ ‘How!’ cried the Barmecide, ‘is it true that at this late hour you have not yet broken your fast? Alas! poor man, you will die of hunger! Here, boy,’ added he, raising his voice, ‘bring us instantly a basin of water, that we may wash our hands.’

“Although no boy appeared, and my brother could see neither basin nor water, the Barmecide began to rub his hands, as if some one held the water for him; and as he did so, he said to my brother, ‘Come hither, and wash with me.’ Schacabac by this supposed that the Barmecide loved his jest; and as he himself was of the same humour, and knew the submission the rich expected from the poor, he imitated all the movements of his host.

“ ‘Come,’ said the Barmecide, ‘now bring us something to eat, and do not keep us waiting.’ When he had said this, although nothing had been brought to eat, he pretended to help himself from a dish, and to carry food to his mouth and chew it, while he called out to my brother, ‘Eat, I entreat you, my guest. You are heartily welcome. Eat, I beg of you: you seem, for a hungry man, to have but a poor appetite.’ ‘Pardon me, my lord,’ replied Schacabac, who was imitating the motions of his host very accurately, ‘you see I lose no time, and understand my business very well.’ ‘What think you of this bread?’ said the Barmecide; ‘don’t you find it excellent?’ ‘In truth, my lord, answered my brother, who in fact saw neither bread nor meat, ‘I never tasted anything more white or delicate.’ ‘Eat your fill then,’ rejoined the Barmecide; ‘I assure you, the slave who made this excellent bread cost me five hundred pieces of gold.’ He continued to praise the female slave who was his baker, and to boast of his bread, which my brother only devoured in imagination. Presently he said, ‘Boy, bring us another dish. Come my friend,’ he continued, to my brother, though no boy appeared, ‘taste this fresh dish, and tell me if you have ever eaten boiled mutton and barley better dressed than this.’ ‘Oh, it is admirable,’ answered my brother, ‘and you see that I help myself very plentifully.’ ‘I am rejoiced to see you,’ said the Barmecide; ‘and I entreat you not to suffer any of these dishes to be taken away, since you find them so much to your taste.’ He presently called for a goose with sweet sauce, and dressed with vinegar, honey, dried raisins, grey peas, and dried figs. This was brought in the same imaginary manner as the mutton. ‘This goose is nice and fat,’ said the Barmecide; ‘here, take only a wing and a thigh, for you must save your appetite, as there are many more courses yet to come.’ In short, he called for many other dishes of different kinds, of which my brother, who felt completely famished, continued to pretend to eat. But the dish the Barmecide praised most highly of all was a lamb stuffed with pistachio nuts, and which was served in the same manner as the other dishes. ‘Now this,’ said he, ‘is a dish you never met with anywhere but at my table, and I wish you to eat heartily of it.’ As he said this he pretended to take a piece in his hand, and put it to my brother’s mouth. ‘Eat this,’ he said, ‘and you will not think I said too much when I boasted of this dish.’ My brother held his head forward, opened his mouth, and pretended to take the piece of lamb, and to chew and swallow it with the greatest pleasure. ‘I was quite sure,’ said the Barmecide, ‘you would think it excellent.’ ‘Nothing can be more delicious,’ replied Schacabac. ‘Indeed, I have never seen a table so well furnished as yours.’ ‘Now bring me the ragout,’ said the Barmecide; ‘and I think you will like it as much as the lamb.—What do you think of it?’ ‘It is wonderful,’ answered my brother: ‘in this ragout we have at once the flavour of amber, cloves, nutmegs, ginger, pepper, and sweet herbs; and yet they are all so well balanced that the presence of one does not destroy the flavour of the rest. How delicious it is!’ ‘Do justice to it then,’ cried the Barmecide, ‘and I pray you eat heartily. Ho! boy,’ cried he, raising his voice, ‘bring us a fresh ragout.’ ‘Not so, my master,’ said Schacabac, ‘for in truth I cannot indeed eat any more.’

“ ‘Then let the dessert be served,’ said the Barmecide: ‘Bring in the fruit.’ He then waited a few moments, to give the servants time to change the dishes; then resuming his speech, he said, ‘Taste these almonds: they are just gathered, and very good.’ They then both pretended to peel the almonds, and eat them. The Barmecide after this invited my brother to partake of many other things. ‘You see here,’ he said, ‘all sorts of fruits, cakes, dried comfits, and preserves; take what you like.’ Then stretching out his hand, as if he was going to give my brother something, he said, ‘Take this lozenge: it is excellent to assist digestion.’ Schacabac pretended to take the lozenge and eat it. ‘There is no want of musk in this, my lord,’ he said. ‘I have these lozenges made at home,’ replied the Barmecide, ‘and in their preparation, as well as everything else in my house, no expense is spared.’ He still continued to persuade my brother to eat, and said, ‘For a man who was almost starving when he came here, you have really eaten hardly anything.’ ‘O my master,’ replied Schacabac, whose jaws were weary of moving with nothing to chew, ‘I assure you I am so full that I cannot eat a morsel more.’

“ ‘Then,’ cried the Barmecide, ‘after a man has eaten so heartily, he should drink a little. You have no objection to good wine?’ ‘My master,’ replied my brother, ‘I pray you to forgive me—I never drink wine, because it is forbidden me.’ ‘You are too scrupulous,’ said the Barmecide; ‘come, come, do as I do.’ ‘To oblige you I will,’ replied Schacabac, ‘for I observe you wish that our banquet should be complete. But as I am not in the habit of drinking wine, I fear I may be guilty of some fault against good breeding, and even fail in the respect that is due to you. For this reason, I still entreat you to excuse my drinking wine; I shall be well satisfied with water.’ ‘No, no,’ said the Barmecide, ‘you must drink wine.’ And he ordered some to be brought. But the wine, like the dinner and dessert, was imaginary. The Barmecide then pretended to pour some out, and drank the first glass. Then he poured out another glass for my brother, and presenting it to him, he cried, ‘Come, drink my health, and tell me if you think the wine good.’

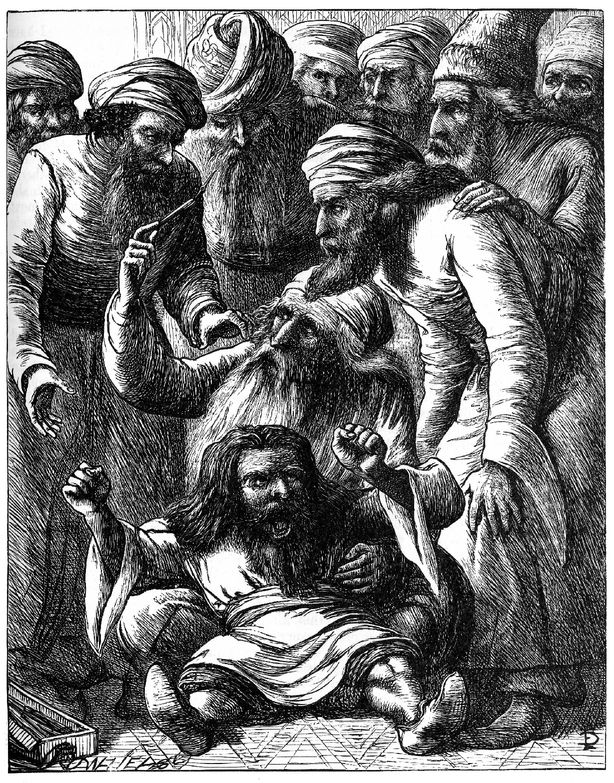

Schacabac knocks down the Barmecide.

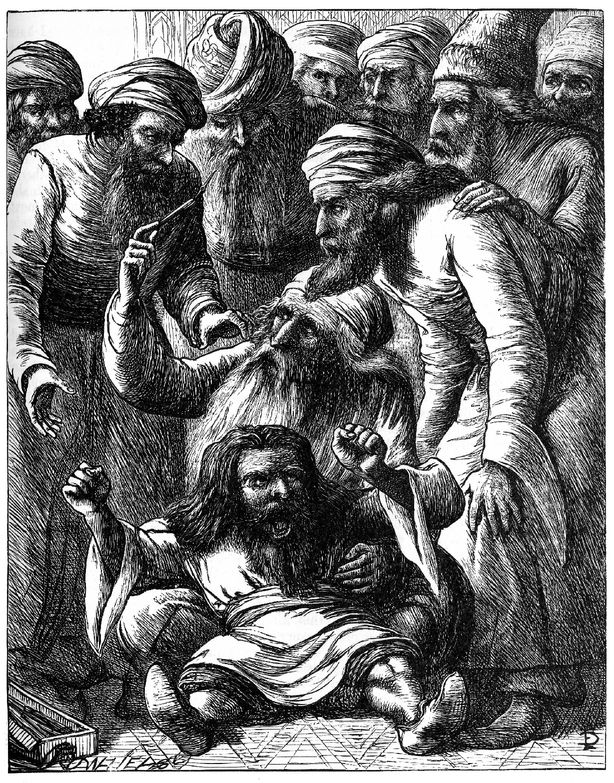

“My brother pretended to take the glass. He held it up, and looked to see if the wine were of a good bright colour; he put it to his nose to test its perfume; then, making a most profound reverence to the Barmecide, to show that he took the liberty to drink his health, he drank it off; pretending that the draught gave him the most exquisite pleasure. ‘My master,’ he said, ‘I find this wine excellent; but it does not seem to me quite strong enough.’ ‘You have only to command,’ replied the other, ‘if you wish for a stronger kind. I have various sorts in my cellar. We will see if this will suit you better.’ He then pretended to pour out wine of another kind for himself and for my brother. He repeated this action so frequently that Schacabac pretended that the wine had got into his head, and feigned intoxication. He raised his hand, and gave the Barmecide such a violent blow that he knocked him down. He was going to strike him a second time, but the Barmecide, holding out his hand to ward off the blow, called out, ‘Are you mad?’ My brother then pretended to recollect himself, and said, ‘O my master, you had the goodness to receive your slave into your house, and to make a great feast for him: you should have been satisfied with making him eat; but you compelled him to drink wine. I told you at first that I should be guilty of some disrespect; I am very sorry for it, and humbly ask your pardon.

“When Schacabac had finished this speech, the Barmecide, instead of putting himself in a great passion and being very angry, burst into a violent fit of laughter. ‘For a long time,’ said he, ‘I have sought a person of your disposition. I not only pardon the blow you have given me, but from this moment I look upon you as one of my friends, and desire that you make my house your home. You have had the good sense to accommodate yourself to my humour, and the patience to carry on the jest to the end; but we will now eat in reality.’ So saying he clapped his hands, and this time several slaves appeared, whom he ordered to set out the table and serve the dinner. His commands were quickly obeyed, and my brother was now in reality regaled with all the dishes he had before partaken of in imagination. As soon as the table was cleared, wine was brought; and a number of beautiful and richly attired female slaves appeared, and began to sing some pleasant airs to the sound of instruments. Schacabac had in the end every reason to be satisfied with the kindness and hospitality of the Barmecide, who took a great fancy to him, and treated him as a familiar friend, giving him moreover a handsome dress from his own wardrobe.

“The Barmecide found my brother possessed of so much knowledge of various sorts, that in the course of a few days he entrusted to him the care of all his house and affairs; and my brother acquitted himself of his charge, during a period of twenty years, to the complete satisfaction of his employer. At the end of that time the generous Barmecide, worn out with old age, paid the common debt of nature; and as he did not leave any heirs, all his fortune fell to the state; my brother was even deprived of all his savings. Finding himself thus reduced to his former state of beggary, he joined a caravan of pilgrims going to Mecca, intending to perform the pilgrimage as a medicant. During the journey the caravan was unfortunately attacked and plundered by a party of Bedouin Arabs, who were more numerous than the pilgrims.

“My brother thus became the slave of a Bedouin, who for many days in succession gave him the bastinado in order to induce him to get himself ransomed. Schacabac protested that it was useless to ill-treat him in this manner. ‘I am your slave,’ said he, ‘and you may dispose of me as you like; but I declare to you that I am in the most extreme poverty, and that it is not in my power to ransom myself.’ My brother tried every expedient to convince the Bedouin of his wretched condition. He endeavoured to soften him by his tears and lamentations. But the Bedouin was inexorable; and through revenge at finding himself disappointed of a considerable sum of money, which he had fully expected to receive, he took his knife and slit my brother’s lips. By this inhuman act he endeavoured to revenge himself for the loss he considered he had suffered.

“This Bedouin had a wife who was rather handsome; and her husband soon after left my brother with her, when he went on his excursions. At such times his wife left no means untried to console Schacabac for the rigour of his situation. She even gave him to understand she was in love with him; but he took every precaution to avoid being alone with her, whenever she seemed to wish it. At length she became so much accustomed to joke and amuse herself with the hard-hearted Schacabac whenever she met him, that she one day forgot herself, and jested with him in the presence of her husband. As ill luck would have it, my poor brother, without in the least thinking he was observed, returned her pleasantries. The Bedouin immediately imagined his slave and his wife loved each other. This suspicion put him into the greatest rage. He sprang upon my brother, and after mutilating him in a barbarous manner, he carried him on a camel to the top of a high rugged mountain, where he left him. This mountain happened to be on the road to Baghdad, and some travellers, who accidently found my brother there, informed me of his situation. I made all the haste I could to the place; and I found the unfortunate Schacabac in the most deplorable condition possible. I afforded him every assistance and aid, and brought him back with me into the city.

“This was what I related to the caliph Montanser Billah,” said the barber in conclusion. “The caliph very much applauded my conduct, and expressed his approval by reiterated fits of laughter. He said to me, ‘They have given you with justice the name of The Silent, and no one can say you do not deserve it. Nevertheless, I have some private reasons for wishing you to leave the city; I therefore order you immediately to depart. Go, and never let me hear of thee again.’ I yielded to necessity, and travelled for many years in distant lands. At length I was informed that the caliph was dead; I therefore returned to Baghdad, where I did not find one of my brothers alive. It was on my return to this city that I rendered to this lame young man the important service of which you have heard. You are also witnesses of his great ingratitude, and of the injurious manner in which he has treated me. Instead of acknowledging his great obligations to me, he has chosen rather to quit his own country in order to avoid me. As soon as I discovered that he had left Baghdad, although no person could give me any information concerning the road he had taken, or tell me into what country he had travelled, I did not hesitate a moment, but instantly set out to seek him. I passed on from province to province; and I accidently met him to-day when I least expected it. And least of all did I expect to find him so irritated against me.”

“Having in this manner related to the Sultan of Casgar the history of the lame young man, and of the barber of Baghdad, the tailor went on as follows:—

“ ‘When the barber had finished his story, we plainly perceived the young man was not wrong when he called him a great chatterer. We nevertheless wished that he should remain with us and partake of the feast which the master of the house had prepared for us. We sat down to table, and continued to enjoy ourselves till the time of the sunset prayers. All the company then separated; and I returned to my shop, where I remained till it was time to shut it up, and go to my house.

“ ‘It was then that the little hunchback, who was half drunk, came to my shop, in front of which he sat down, and sang to the sound of his timbrel. I thought that by taking him home with me I should afford some entertainment to my wife; and it was for this reason only that I invited him. My wife gave us a dish of fish for supper. I gave some to the little hunchback, who began to eat without taking sufficient care to avoid the bones; and presently he fell down senseless before us. We tried every means in our power to relieve him, but without effect; and then, in order to free ourselves from the embarrassment into which this melancholy accident had thrown us, and, in the great terror of the moment, we did not hesitate to carry the body out of our house, and induce the Jewish physician to receive it in the manner your majesty has heard told. The Jewish physician let it down into the apartment of the purveyor, and the purveyor carried it into the street, where the merchant thought he had killed the poor man. This, O sultan,’ added the tailor, ‘is what I have to say to your majesty in my justification. It is for you to determine whether we are worthy of your clemency or anger; whether we deserve to live or die.’

“The Sultan of Casgar’s countenance expressed so much satisfaction and favour that it gave new courage to the tailor and his companions. ‘I cannot deny,’ said the monarch, ‘that I am more astonished at the history of the lame young man and of the barber, and the adventures of his brothers, than at anything in the history of my buffoon. But before I send you all four back to your own houses, and order the little hunchback to be buried, I wish to see this barber, who has been the cause of your pardon. And since he is now in my capital, it will not be difficult to produce him.’ He immediately ordered one of his attendants to go and find the barber out, and to take with him the tailor, who knew where the silent man was.

“The officer and the tailor soon returned, and brought back with them the barber, whom they presented to the sultan. He appeared a man of about ninety years of age. His beard and eyebrows were as white as snow; his ears hung down to a considerable length, and his nose was very long. The sultan could scarcely refrain from laughter at the sight of him. ‘Man of silence,’ said he to the barber, ‘I understand that you are acquainted with many wonderful histories. I desire that you will relate one of them to me.’ ‘O sultan!’ replied the barber, ‘for the present, if it please your majesty, we will not speak of the histories which I can tell; but I most humbly entreat permission to ask one question, and to be informed for what reason this Christian, this Jew, this Mussulman, and this hunchback, whom I see extended on the ground, are in your majesty’s presence.’ The sultan smiled at the freedom of the barber, and said, ‘What can that matter to thee?’ ‘O sultan! ’ returned the barber, ‘it is of importance that I should make this inquiry, in order that your majesty may know that I am not a great talker, but, on the contrary, a man who has very justly acquired the title of The Silent.”

“The Sultan of Casgar graciously satisfied the barber’s curiosity. He desired that the adventures of the little hunchback should be related to him, since the old man seemed so very anxious to hear it. When the barber had heard the whole story, he shook his head, as if there were something in the tale which he could not well comprehend. ‘In truth,’ he exclaimed, ‘this is a very wonderful history: but I should vastly like to examine this hunchback a little more attentively.’ He then drew near to him, and sat down on the ground. He took the hunchback’s head between his knees, and after examining him very closely he suddenly burst out into a violent fit of mirth, and laughed so immoderately that he fell backwards, without at all considering that he was in the presence of the Sultan of Casgar. He got up from the ground, still laughing heartily. ‘You may very well say,’ he at length cried, ‘that no man dies without a cause. If ever a history deserved to be written in letters of gold, it is this of the hunchback.’

“At this speech every one looked upon the barber as a buffoon, or an old madman, and the sultan said:

“ ‘Man of silence, answer me: what is the reason of your clamorous laughter?’ ‘O sultan!’ replied the barber, ‘I swear by your majesty’s good-nature that this hunchback fellow is not dead: there is still life in him; and you may consider me a fool and a madman if I do not instantly prove it to you.’ Hereupon he produced a box in which there were various medicines, and which he always carried about with him, to use on any emergency. He opened it, and taking out a phial containing a sort of balsam, he rubbed it thoroughly and for a long time into the neck of the hunchback. He then drew out of a case an iron instrument of peculiar shape, with which he opened the hunchback’s jaws; and thus he was enabled to put a small pair of pincers into the patient’s throat, and drew out the fish-bone, which he held up and showed to all the spectators. Almost immediately the hunchback sneezed, stretched out his hands and feet, opened his eyes, and gave many other proofs that he was alive.

“The Sultan of Casgar, and all who witnessed this excellent operation, were less surprised at seeing the hunchback brought to life, although he had passed a night and almost a whole day without the least apparent sign of animation, than delighted with the merit and skill of the barber, whom they now began to regard as a very great personage in spite of all his faults. The sultan was so filled with joy and admiration that he ordered the history of the hunchback, and that of the barber, to be instantly committed to writing, that the knowledge of a story which so well deserved to be preserved might never be forgotten. Nor was this all. In order that the tailor, the Jewish physician, the purveyor, and the Christian merchant might ever remember with pleasure the adventures which the hunchback’s accident had caused them, he gave to each of them a very rich robe, which he made them put on in his presence before he dismissed them. And he bestowed upon the barber a large pension, and kept him ever afterwards near his own person.”

The barber extracts the bone from the hunchback’s throat.

Thus the Sultana Scheherazade finished the story of the long series of adventures to which the supposed death of the hunchback had given rise. Her sister Dinarzade, observing that Scheherazade had done speaking, said to her: “My dear princess, my sultana, I am much the more delighted with the story you have just finished, from the unexpected incident by which it was brought to a conclusion. I really thought the little hunchback was quite dead.” “This surprise has also afforded me pleasure,” said Shahriar: “I have also been entertained by the adventures of the barber’s brothers.” “The history of the lame young man of Baghdad has also very much diverted me,” rejoined Dinarzarde. “I am highly satisfied, my dear sister,” replied Scheherazade, “that I have been able thus to entertain you and the sultan our lord and master; and since I have had the good fortune not to weary his majesty, I shall have the honour, if he will have the goodness to prolong my life still further, to relate to him the history of the Noureddin and the beautiful Persian—a story not less worthy than the history of the hunchback to attract his attention and yours.” The Sultan of India, who had been much entertained by everything Scheherazade had hitherto related, was determined not to forego the pleasure of hearing this new history which she promised. He therefore arose and went to prayers, and then sat in council; and the next morning Dinarzade did not fail to remind her sister of her promise, and Scheherazade began her new story in the following words:—