THE HISTORY OF ABOULHASSAN ALI EBN BECAR, AND OF SCHEMSELNIHAR, THE FAVOURITE OF THE CALIPH HAROUN ALRASCHID.

DURING the reign of the Caliph Haroun Alraschid, there lived at Baghdad a druggist whose name was Aboulhassan Ebn Thaher. He was a man of considerable wealth, and was also very handsome, and reckoned an agreeable companion. He possessed more understanding and more politeness than can be generally found among people of his profession. His ideas of rectitude, his sincerity, and the liveliness of his disposition made him beloved and sought after by every one. The caliph, who was well acquainted with his merit, placed the most implicit confidence in him. He esteemed him so highly that he even entrusted to him the sole care of procuring for his favourite ladies everything they required. It was the druggist who chose their dresses, the furniture of their apartments, and their jewellery, and in all his purchases he gave proofs of a most excellent taste.

“His various good qualities and the favour of the caliph caused the sons of the emirs and other officers of the highest rank to frequent this man’s house, which, in this manner, became the rendezvous of all the nobles of the court. Among other young nobles who made almost a daily practice of going there, was one whom Ebn Thaher esteemed above all the rest, and with whom he contracted a most intimate friendship. This young nobleman’s name was Aboulhassan Ali Ebn Becar, and he derived his origin from an ancient royal family of Persia. This family still continued to live at Baghdad from the time when the Mussulman arms made a conquest of that kingdom. Nature seemed to have taken pleasure in combining in this young prince every mental endowment and personal accomplishment. He possessed a countenance of the most finished beauty. His figure was fine, his air elegant and easy, and the expression of his face so engaging that no one could see him without instantly loving him. Whenever he spoke he used the most appropriate words, and his every speech had a certain turn of expression equally novel and agreeable. There was something even in the tone of his voice that charmed all who heard him. To complete the description of him, as his understanding and judgment were of the first rank, so all his thoughts and expressions were most admirable and just. He was moreover so reserved and modest, that he never made an assertion till he had taken every possible precaution to avoid all suspicion of preferring his own opinions or sentiments to those of others. It is not to be wondered at that Ebn Thaher distinguished this excellent young prince in a particular manner from the other young noblemen of the court, whose vices, for the most part, served only to make his virtues appear the more brilliant by contrast.

“The prince was one day at the house of Ebn Thaher when a lady came to the door, mounted upon a black and white mule, and surrounded by ten female slaves, who accompanied her on foot. These slaves were all very handsome, as far as could be judged from their air and through the veils that covered their faces. The lady herself wore a rose-coloured girdle at least four fingers in width, upon which were fastened diamonds and pearls of the largest size; and it was no difficult matter to conjecture that her beauty surpassed the charms of her attendants as much as the moon at its full exceeds the crescent of two days old. She came for the purpose of executing some commission; and as she desired to speak to Ebn Thaher, she went into his shop, which was very large and commodious. He received her with every mark of respect, begged her to be seated, and, taking her by the hand, conducted her to the most honourable place.

“The Prince of Persia in the meantime did not choose to neglect such an excellent opportunity of showing his politeness and his gallantry. He placed a cushion, covered with cloth of gold for the lady to rest upon, and then immediately retired, that she might sit down. After this he made his obeisance by kissing the carpet at her feet, then rose and stood before her at the end of the sofa. As the lady felt herself quite at home in Ebn Thaher’s house, she took off her veil, and displayed to the eyes of the Prince of Persia a beauty so extraordinary that it pierced him to the bottom of his heart. Nor could the lady on her part help looking at the prince, whose appearance made an equal impression on her. She said to him in an obliging manner, ‘I beg you, my lord, to be seated.’ The Prince of Persia obeyed, and sat down on the edge of the sofa. He kept his eyes constantly fixed upon the beautiful lady, and swallowed large draughts of the delicious poison of love. She soon perceived what passed in his mind, and this discovery aroused a kindred feeling in her own breast. She rose and went to Ebn Thaher, and after she had imparted to him, in a whisper, the motive of her visit, she inquired of him the name and country of the Prince of Persia. ‘O lady,’ replied Ebn Thaher, ‘this young prince, of whom you are speaking, is called Aboulhassan Ali Ebn Becar, and is of the blood royal of Persia.’

“The lady was delighted to find that the man whose appearance had won her esteem was of such a high rank. She replied: ‘I understand from what you say that he is descended from the kings of Persia.’ ‘In truth, lady,’ returned Ebn Thaber, ‘the kings of Persia are his ancestors; and since the conquest of that kingdom, the princes of his family have always been held in esteem at the court of our caliphs.’ ‘You will do me a great favour,’ said the lady, ‘if you will make me acquainted with this young prince.’ She added: ‘I shall shortly send this attendant,’ pointing to one of her slaves, ‘to request you to come and see me, and I beg you will bring him with you; I very much wish him to see the splendour and magnificence of my palace, that he may publish to the world that avarice does not hold her court among people of rank at Baghdad. Understand and give heed to my words. Fail not to remember my request. If you do I shall be very angry with you, and will never come and see you again so long as I live.’

“Ebn Thaher possessed too much penetration not to understand by this speech what were the sentiments of the lady. ‘Allah forbid, my princess,’ replied he, ‘that I should give you any cause to be offended with me. To execute your orders will ever be my delight.’ Having received this answer, the lady took leave of Ebn Thaher by an inclination of her head; and after casting a most obliging look at the Prince of Persia, she mounted her mule and departed.

“The prince was violently moved with admiration for this lady. He continued looking at her as long as she was in sight; and even after she had disappeared it was a long time before he turned away his eyes from the direction in which she had gone. Ebn Thaher then remarked to him that he was observed by some people, who were inclined to make merry at his expense. ‘Alas!’ said the prince, ‘you and all the world would have compassion upon me if you knew that this beautiful lady, who has just left your house, had carried away by far the better part of me; and that what remains cannot live separate from her. Tell me, I conjure you,’ added he, ‘who this tyrannical lady is that thus compels people to love her without giving them time to combat their feelings?’ ‘My lord,’ replied Ebn Thaher, ‘that lady is the famous Schemselnihar, the first favourite of our sovereign master the caliph.’ The prince rejoined: ‘She is indeed with great justice and propriety named Schemselnihar, since she is more beautiful than the cloudless meridian sun.’ ‘It is true,’ cried Ebn Thaher; ‘and the Commander of the Faithful loves her, or I may rather say, adores her. He has expressly commanded me to furnish her with everything she wishes, and even to anticipate her thoughts, if it were possible, in anything she may desire.’

“Ebn Thaher told all these particulars to the prince to prevent the young man from giving way to a passion which could only end unfortunately; but the druggist’s words only served to inflame him the more. ‘I cannot hope,’ cried he, ‘charming Schemselnihar, that I shall be suffered to raise my thoughts to you. I nevertheless feel, although I am destitute of all hope of being beloved by you, that it will not be in my power to cease from adoring you. Therefore I will continue to love you, and will bless the fate that has made me the slave of the most beautiful object that the sun shines on.’

“While the Prince of Persia was thus consecrating his heart to the beautiful Schemselnihar, that lady, as she went home, continued to think upon the means she should pursue in order to see and converse with freedom with this prince. So soon as she reached the palace she sent back to Ebn Thaher the female slave whom she had pointed out to him, and in whom she placed the most implicit confidence. The slave brought to the druggist a request that he would see her mistress without delay, and bring the Prince of Persia with him. The slave arrived at the shop of Ebn Thaher while he was still conversing with the prince, and while he was using the strongest arguments in his endeavour to persuade him to think no more of the favourite of the caliph. When the slave thus saw them talking together she said, ‘My most honourable mistress Schemselnihar, the first favourite of the Commander of the Faithful, entreats you both to come to the palace, where she awaits you.’ In order to show how ready he was to obey the summons, Ebn Thaher instantly got up, without answering the slave one word, and followed her, though with much inward reluctance. As for the prince, he followed her without at all reflecting on the perils which might arise to him from this visit. The presence of Ebn Thaher, who had free admission to the favourite, made him feel perfectly at his ease. The two men followed the slave, who walked a little in advance of them. They went into the palace of the caliph, and joined her at the door of the smaller palace appropriated to Schemselnihar, which was already open. The slave introduced them into a large hall, and motioned them to be seated.

“The Prince of Persia thought himself in one of those delightful abodes which are promised to us in a future world. He had hitherto seen nothing that at all approached the magnificence of the place where he now was. The carpets, cushions, and coverings of the sofas, together with the furniture, ornaments, and decorations, were most exceeding rich and beautiful. The visitors had not long remained in this apartment, before a black slave, handsomely dressed, brought in a table covered with the most delicate dishes, the delicious fragrance of which gave token of the richness of the repast prepared for them. While they were eating, the slave who had conducted them to the palace did not leave them: she was very diligent in pressing them to eat of those ragouts and dishes she knew to be best. In the meantime other slaves poured them out some excellent wine, with which they regaled themselves. When the feast was over, the attendants presented to the Prince of Persia and to Ebn Thaher each a separate basin, and a beautiful golden vase, full of water, to wash their hands. They afterwards brought them some perfume of aloes in a beautiful vessel, which was also of gold, and with this perfume the guests scented their beards and dress. Nor was the perfumed water forgotten. It was brought in a golden vase made expressly for this purpose, enriched with diamonds and rubies, and it was poured into both their hands, with which they rubbed their beards and their faces, according to the usual custom. They then sat down again in their places; but in a very few moments the slave requested them to rise up and follow her. She opened a door which led from the hall where they had feasted; and they entered a very large saloon wonderfully constructed. The ceiling was a dome of elegant form, supported by a hundred columns of marble as white as alabaster. The pedestals and capitals of these columns were all ornamented with quadrupeds and birds of various species, worked in gold. The carpet of this splendid saloon was composed of a single piece of cloth of gold, upon which were worked bunches of roses in red and white silk; the dome itself was painted in arabesque, and exhibited to the spectator a multitude of charming objects. There was a small sofa in every interval between the columns, ornamented in the same manner, together with large vases of porcelain, of crystal, jasper, jet, porphyry, agate, and other valuable materials, all enriched with gold and inlaid with precious stones. The spaces between the columns contained also large windows, with balconies of a proper height, and furnished in the same style of elegance as the sofas, with a view into the most delicious garden in the world. The walks in this garden were formed of small stones of various colours, which represented the carpet of the saloon under the dome; and in this manner, when the spectator turned his eyes towards the ground, either in the saloon or garden, it seemed as if the dome and the garden, with all their beauties, formed one splendid whole. The view from every point was terminated at the end of the walks by two pieces of water, as transparent as rock crystal, in which the circular figure of the dome was reproduced. One of these was raised above the other, and from the higher the water fell in a large sheet into the lower one. On their banks, at certain distances, were placed beautiful bronze and gilt vases, all decorated with shrubs and flowers. These walks also separated from each other large lawns, which were planted with lofty and thick trees, in whose branches a thousand birds warbled the most melodious sounds, and diversified the scene by their various flights, and by the battles they fought in the air, sometimes in sport, and at others in a more serious and cruel manner.

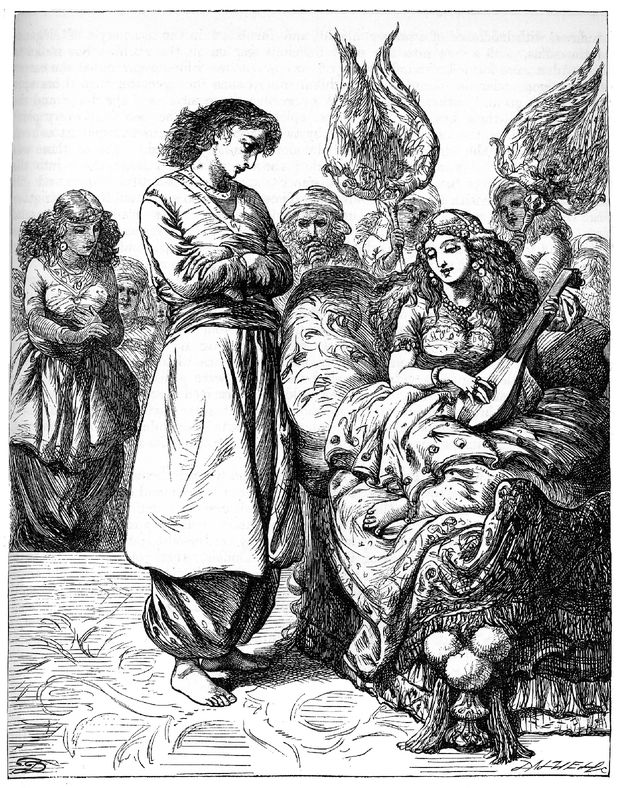

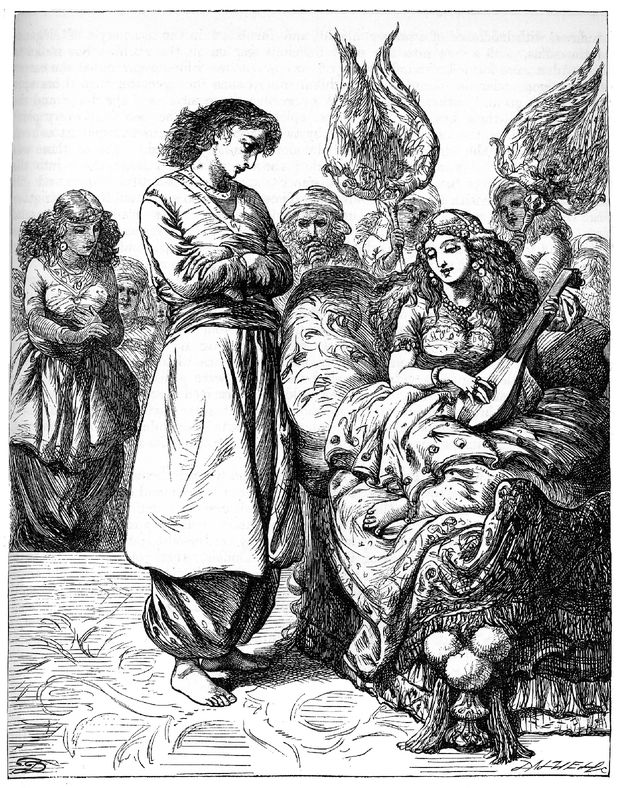

The concert at the palace of Schemselnihar.

“The Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher stopped a long time to examine the great magnificence of this place. They expressed strong marks of surprise and admiration at everything that struck them. The Prince of Persia especially had never before seen anything at all comparable to this dwelling. Ebn Thaher, too, although he had been before in this enchanting spot, could not refrain from admiring its beauties, which always appeared to possess an air of novelty. In short, the guests had not ceased from their admiration of the singular spectacle around them, and were still agreeably engaged in examining its various beauties, when they suddenly perceived a company of ladies very richly dressed. They were all sitting in the garden, at some distance from the dome, each on a seat made of Indian plantain wood, enriched with silver inlaid in compartments. Each had a musical instrument in her hands, and seemed waiting for the appointed signal to begin to play on it.

“Ebn Thaher and the Prince of Persia went and placed themselves in one of the balconies, from whence they had a direct view of these ladies; and on looking towards the right hand, they saw before them a large court, with an entrance into the garden up a flight of steps. The whole of this court was surrounded with very elegant apartments. The slaves had left them, and as they were alone, they conversed together for some time. ‘I do not doubt,’ said the Prince of Persia to Ebn Thaher, ‘that you, who are a sedate and wise man, look with very little satisfaction upon all this exhibition of magnificence and power. In my eyes nothing in the whole world can be more surprising; and when I add to this reflection the thought that it is the splendid abode of the too beautiful Schemselnihar, and that the foremost monarch of the world makes it the place of his retreat, I confess to you that I think myself the most unfortunate of men. It seems to me that there cannot be a more cruel fate than mine, for I love a being who is completely in the power of my rival; and being in the very spot where my rival is so powerful, I am at this very instant not even secure of my life.’

“To this speech of the Prince of Persia Ebn Thaher thus replied: ‘Would to Allah, O prince, that I could give you as perfect an assurance of the happy issue of your attachment as I can of the safety of your person. Although this superb palace belongs to the caliph, it was erected expressly for Schemselnihar, and is called the Palace of Continual Pleasures; and although it forms a part, as it were, of the sultan’s palace, yet be assured this lady here enjoys the most perfect liberty. She is not surrounded by eunuchs placed to watch her minutest actions. These buildings are appropriated to her sole use, and she has absolute power to dispose of the whole as she thinks proper. She goes out and walks about the city wherever she pleases, without asking leave of any one; she returns at her own time; and the caliph never comes to visit her without first sending Mesrour, the chief of the eunuchs, to give her notice of his intention, that she may have time to prepare for his reception. Your mind, therefore, need not be disturbed, but you may consider yourself in perfect safety to listen to the concert with which I perceive Schemselnihar is going to entertain us.’

“At the very instant when Ebn Thaher had done speaking, the Prince of Persia and he both observed the slave who was the confidante of the favourite, come and order the women seated in front of them to sing, and play on their several instruments. They all immediately began a sort of prelude, and after playing thus for some time, one of them sang alone, and accompanied herself on a lute most admirably. As she had been informed of the subject upon which she was to sing, the words of her song were in such perfect unison with the feelings of the Prince of Persia, that he could not help applauding her at the conclusion of the strain. ‘Is it possible, ’ he cried, ‘that you can have the faculty of penetrating the inmost thoughts of others, and that the knowledge you have of what passes in my heart has enabled you to give my feelings utterance in the sound of your delightful voice? I could not myself have expressed in more appropriate terms the passion of my heart.’ To this speech the minstrel answered not a word. She resumed, and sang several other stanzas, which so much affected the Prince of Persia, that he repeated some of them with tears in his eyes; and that he applied the song to Schemselnihar and himself was sufficiently evident. When the lady had finished all the couplets, she and her companions stood up and sang all together some words to the following effect: The full moon is going to arise in all its splendour, and will soon approach the sun. The meaning of which was, that Schemselnihar was about to appear, and that the Prince of Persia would immediately have the pleasure of seeing her.

“Indeed, looking towards one side of the court, Ebn Thaher and the prince observed the confidential slave approach, followed by ten black females, who with difficulty carried a large throne of massive silver most elegantly wrought, which the slave made them place at a certain distance from the prince and Ebn Thaher. After they had deposited their burden, the black slaves retired behind some trees at the end of a walk. Then twenty very beautiful females, richly and uniformly dressed, advanced in two rows, singing and playing on different instruments; and they ranged themselves on each side of the throne.

“The Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher beheld all these preparations with the greatest possible attention, eager and curious to know in what the scene would end. At last they saw, issuing from the same door whence the ten black slaves who had brought the throne and the twenty other slaves had emerged, ten other women, as beautiful and as handsomely adorned as the first group. They stopped at the door for some moments waiting for the favourite, who then issued forth, and placed herself in the midst of them. It was very easy to distinguish her from the rest, alike by her beauteous person and majestic air, and by a sort of mantle, of very light materials enriched with azure and gold, which she wore fastened to her shoulders over the rest of her dress, which was the most appropriate, the most elegant, and the most magnificent that could be. The diamonds, pearls, and rubies which ornamented her garb were not scattered in a confused manner: they were few in number, properly arranged, and of inestimable value. She advanced with a degree of majesty which might well be likened to that of the sun in his course, in the midst of clouds which receive its rays without diminishing its splendour. She then proceeded, and seated herself upon the silver throne that had been brought for that purpose.

“As soon as the Prince of Persia perceived Schemselnihar, he had eyes only for her. ‘We cease our inquiries after the object of our search,’ said he to Ebn Thaher, ‘when it appears before us; and we are no longer in a state of doubt when the truth is evident. Look at this divine beauty: she is the cause of all my sufferings; sufferings, indeed, which I bless, however severe they have been, and however lasting they may prove. When I behold this charming creature, I am no longer myself: my restless soul revolts against its master, and I feel that it strives to fly from me. Go, then, my soul; I permit thee to stray; but let thy flight be for the advantage and preservation of this weak frame. It is you, too cruel Ebn Thaher, who are the cause of my woes. You thought to give me pleasure by bringing me here; and I find that I am come only to court my destruction.—Pardon me,’ he added, recovering himself a little; ‘I deceive myself, for I was determined to come, and can accuse only my own folly.’ At these words he wept violently. ‘I am rejoiced to find,’ said Ebn Thaher, ‘that you at least do me justice. When I told you that Schemselnihar was the first favourite of the caliph, I did so for the express purpose of nipping this direful and fatal passion, which you seem to take a pleasure in nourishing in your heart. Everything you see here ought to make you endeavour to disengage yourself, and should excite in you only sentiments of gratitude and respect for the honour Schemselnihar has been willing to do you, when she ordered me to introduce you here. Therefore be a man; recall your wandering reason, and be ready to appear before her in a way her kindness and condescension deserve. See, she approaches. If these things were to happen again, I would in truth act very differently; but the thing is done, and I trust in Allah that we shall not have to repent it. I have nothing more to say,’ added he, ‘but that love is a traitor who, if you give him sway, will plunge you in an abyss from which you can never again extricate yourself.’

“Ebn Thaher had no time to say more, as Schemselnihar now came up. She seated herself on the throne, and saluted both her visitors with an inclination of her head. Her eyes, however, were fixed only upon the prince. He was not slow to answer her in the same way, and they both spoke a silent language intermingled with sighs, by which, in a short time, they uttered more than they would have said in an age in actual conversation. The more Schemselnihar looked at the prince, the more did his looks tend to confirm her opinion that she was not indifferent to him; and, thus convinced of his passion, Schemselnihar thought herself the happiest being in the whole world. At length she ceased gazing at him, and ordered the women who had sung to approach. They rose up, and as they came forward the black slaves came from the walk where they had remained, and brought their seats, and placed them near the balcony, in the window of which the Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher were. They were arranged in such a way that, together with the favourite’s throne, and the women who were on each side of her, they formed a semicircle before the two guests.

“When those who had before been seated had again taken their places, by the permission of Schemselnihar, who gave them a sign for that purpose, the charming favourite desired one of her women to sing. After employing a little time in tuning her lute, the woman sang a song, the words of which had the following meaning:—When two lovers, who are sincerely fond of each other, are attached by a boundless passion; when their hearts, although in two bodies, form but one; when an obstacle opposes their union, they may well say mournfully, with tears in their eyes, ‘If we love each other, because each finds the other amiable, ought we to be censured? Fate alone is to blame: we are innocent.’

“Schemselnihar evidently showed, both by her looks and manner, that she thought these words applicable to herself and the prince; and he was no longer master of himself. He rose, and advancing towards the balustrade, he leaned his arm upon it, and coutrived to catch the attention of one of the women who sang. As she was not far from him, he said to her, ‘Listen to me, and do me the favour to accompany with your lute the song I am now going to sing.’ He than sang an air, the tender and impassioned words of which perfectly expressed the violence of his love. As soon as it was finished, Schemselnihar, following his example, said to one of her women, ‘At- tend to me also, and accompany my voice.’ She then sang in a manner that increased and heightened the flame that burnt in the heart of the Prince of Persia, who only answered her by another air still more tender and impassioned than the one he had sung before.

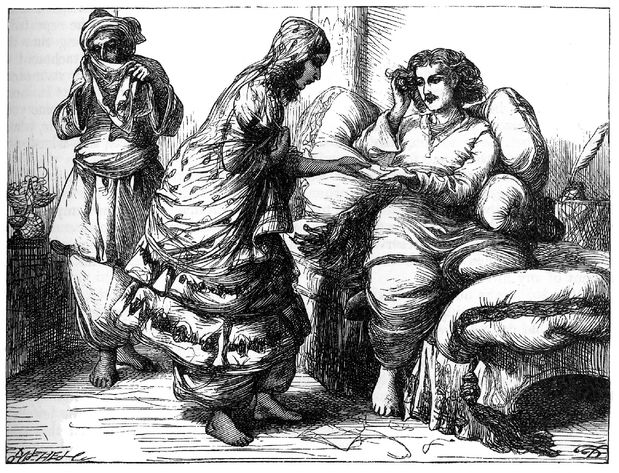

“These two lovers having thus declared their mutual affection by their songs, Schemselnihar at length completely yielded to the strength of her feelings. She rose from her throne, almost forgetting what she did, and proceeded towards the door of the saloon. The prince, who was aware of her intention, instantly rose also, and hurried to meet her. They encountered each other at the very door, where they seized each other’s hands, and embraced with so much transport that they both fainted on the spot. They would have fallen to the ground, if the female attendants who followed Schemselnihar had not supported them. They bore them in their arms to a sofa; and by throwing perfumed water over them, and applying various stimulants, they restored the prince and Schemselnihar to their senses.

“The first thing Schemselnihar did, as soon as she had recovered, was to look round on all sides; and not seeing Ebn Thaher, she eagerly inquired where he was. Ebn Thaher had retired out of respect to her, while the slaves were employed in attending their mistress; for he greatly feared, and not without reason, that some unfortunate consequence would arise from this adventure. As soon as he heard that Schemselnihar had asked for him, he came forward and presented himself before her.

“She seemed highly satisfied at the appearance of Ebn Thaher, and expressed her joy in these flattering words: ‘I know not, Ebn Thaher, by what means I can ever repay the obligations I am under to you; but for you I should never have become acquainted with the Prince of Persia, nor have gained the affections of the most amiable being in the world. Be assured, however, that I shall not be ungrateful, and that my gratitude shall, if possible, equal the benefit I have received through your means.’ Ebn Thaher could only answer this obliging speech by an inclination of his head, and by wishing the favourite the attainment of every blessing she could desire.

“Schemselnihar then turned towards the Prince of Persia, who was seated by her side; and looking at him, not without confusion at the thought of what had passed between them, she said to him: ‘My friend, I cannot but be perfectly assured that you love me; and however strong your passion for me may be, you cannot, I think, doubt that it is thoroughly reciprocated. But do not let us delusively flatter ourselves; whatever unison there may be between your sentiments and mine, I can look forward only to pain, disappointment, and misery for us both. And no consolation, alas! remains to befriend us in our misfortunes, but perfect constancy in love, entire submission to the will of Heaven, and patient expectation of whatever it may please to decree as our destiny.’

“ ‘O lady,’ replied the Prince of Persia, ‘you would do me the greatest injustice in the world, if you could for a moment doubt the constancy and fidelity of my heart. My affection has so completely taken possession of my soul, that it forms in fact a part of my very existence; nay, I shall even preserve it beyond the grave. Neither misery, torments, nor obstacles of any kind can ever succeed in lessening my love for you.’ At the conclusion of this speech his tears flowed in abundance; nor could Schemselnihar restrain her own grief.

“Ebn Thaher took this opportunity to speak to the favourite. ‘O my mistress,’ said he, ‘permit me to say that, instead of thus despairing, you and the prince ought rather to feel the greatest joy in finding yourselves so fortunately in each other’s society. I do not understand the motive for your grief. If it overwhelms you already, what must you feel when necessity shall compel you to separate? But why do I say ‘shall compel’ you? we have already tarried too long here, and, lady, you must know that it is now necessary we should take our departure.’ ‘Alas!’ replied Schemselnihar, ‘how cruel you are! Have not you, who well know the cause of my tears, any pity for the unfortunate situation in which you see me? Oh, miserable destiny! why am I compelled to submit to the hardship of being for ever unable to be united to him who absorbs my whole affection?’

“As, however, she was well persuaded that Ebn Thaher had said nothing but what was dictated by friendship, she was by no means angry at his speech. She even profited by it; for she directly made a sign to the slave her confidante, who immediately went out, and soon returned with a small collation of various fruits upon a silver table, which she placed between the favourite and the Prince of Persia. Schemselnihar chose the fruit she thought the most delicate, and presented it to the prince, entreating him to eat it for her sake. He took it, and instantly carried it to his mouth, taking care that the very part which had felt the pressure of her fingers should first touch his lips. The prince in his turn then presented some fruit to Schemselnihar, who directly took and ate it in the same manner. Nor did she forget to invite Ebn Thaher to partake of the collation with them: but as he knew he was now staying in the palace longer than was perfectly safe, he would rather have returned home, and he therefore joined them only through complaisance. As soon as the table had been removed, the slaves brought some water in a vase of gold, and a silver basin, in which the two friends washed their hands at the same time. After this they returned to their seats, and then three of the ten black women brought each, upon a golden tray, a cup formed of beautiful rock crystal, and filled with the most exquisite wine, which they placed before Schemselnihar, the Prince of Persia, and Ebn Thaher.

“In order to be more at her ease, Schemselnihar retained near her only the ten black slaves and the other ten women who were skilled in music and singing. After she had dismissed all the remaining attendants, she took one of the cups, and holding it in her hand, she sang some tender words, while one of the females accompanied her voice with a lute. When this was finished she drank the wine. She then took one of the other cups, and, presenting it to the prince, requested him to drink it for love of her in the same manner as she had drunk hers. He received it in a transport of love and joy. But before he drank the wine he sang in his turn an air, accompanied by the instrument of another woman; and while he sang the tears fell in abundance from his eyes: the words also which he sang expressed the idea that he knew not whether it was the wine that he was drinking, or his own tears. Schemselnihar then presented the third cup to Ebn Thaher, who thanked her for the honour and attention she had shown him.

“When this was over, the favourite took a lute from one of the slaves, and accompanied her own voice in so impassioned a manner that she was absolutely carried beyond herself; and the Prince of Persia, with his eyes intently fixed upon her, remained perfectly motionless, like one enchanted. In the midst of this scene the trusty slave of the favourite entered in great alarm, and told her mistress that Mesrour and two other officers, accompanied by a number of eunuchs, were at the door, and desired to speak of her, bringing a message from the caliph. When the Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher heard what the slave said, they changed colour and trembled, as if they had been betrayed. Schemselnihar, however, who perceived this, soon dispelled their fears.

“After she had endeavoured to quiet their alarm, she charged her confidential slave to go and keep Mesrour and the two officers of the caliph in conversation while she prepared herself to receive them; and said she would then send to have them introduced. She directly ordered all the windows of the saloon to be shut, and the paintings on silk, which were in the garden, to be taken down; and after having again assured the prince and Ebn Thaher that they might remain where they were in perfect safety, she opened the door that led to the garden, went out, and shut it after her. In spite, however, of all her assurances that they were quite secure from discovery, they could not avoid feeling very much alarmed all the time they were alone.

“As soon as Schemselnihar came into the garden with the women who attended her, she made them take away all the seats on which the women who had sung and played had sat, near the window from whence the prince and Ebn Thaher had heard them. When she saw that everything was arranged as she wished, she sat down on the silver throne, and then sent to inform her confidential slave that she might introduce the chief of the eunuchs and the two officers who accompanied him.

“They appeared, followed by twenty black eunuchs, all handsomely dressed. Each of them had a scimitar by his side, and a large golden belt round his body four fingers in breadth. As soon as they saw the favourite, although they were still at a considerable distance from her, they made a most profound reverence, which she returned them from her throne. When they approached nearer she rose up, and went towards Mesrour, who walked first. She asked him what was his errand; to which he replied, ‘O lady, the Commander of the Faithful, by whose orders I am come, has charged me to say to you that he cannot live any longer without the pleasure of beholding you. He purposes, therefore, to pay you a visit this evening; and I am come in order to inform you of this, that you may prepare for his reception. He hopes, my mistress, that you will feel as much joy in receiving him as he feels impatience to behold you.’

“When the favourite observed that Mesrour had finished his speech, she prostrated herself on the ground, to show the submission with which she received the commands of the caliph. When she rose she said to him, ‘I beg you will inform the Commander of the Faithful that it will ever be my glory to fulfil the commands of his majesty, and that his slave will endeavour to receive him with all the respect that is due to him.’ At the same time she gave orders to her confidential slave to make all the necessary preparations in the palace for the caliph’s reception, by the hands of the black slaves who were kept for this purpose. Then, in dismissing the chief of the eunuchs, she said to him, ‘You must see that the necessary preparations will occupy some time; go, therefore, I pray you, and arrange matters so that the caliph may not be very impatient, and that he may not arrive so soon as to find us quite in confusion.’

“The chief of the eunuchs then retired with his attendants; and Schemselnihar returned to the saloon very much grieved at the necessity she was under of sending the Prince of Persia away sooner than she had intended. She went to him with tears in her eyes; and her apparent confusion very much increased the alarm of Ebn Thaher, who seemed to conjecture from it some unfortunate event. ‘I see, O lady,’ said the prince to her, ‘that you come for the purpose of announcing to me that we must separate. If, however, this is the only misfortune I have to dread, I trust that Heaven will grant me patience, which I greatly need, to enable me to support your absence. ’ ‘Alas! my love, my dear life,’ cried the tender Schemselnihar, interrupting him, ‘how happy do I find your lot when I compare it with my more wretched fate! You doubtless suffer greatly from my absence, but that is your only grief; you can derive consolation from the hopes of seeing me again; but I—just Heaven! to what a painful task am I condemned! I am not only deprived of the enjoyment of the only being I love, but am obliged to bear the sight of one whom you have rendered hateful to me. Will not the caliph’s arrival constantly bring to my recollection the necessity of your departure? And absorbed as I shall be continually with your dear image, how shall I be able to express to that prince any sign of joy at his presence?—I who have hitherto always received him, as he often remarks, with pleasure sparkling in my eyes! When I address him my thoughts will be distracted; and when I must speak to him in the language of affection, my words will be a dagger in my very soul! Can I possibly derive the least pleasure from his kind words and caresses? How dreadful is the idea! Judge, then, my prince, to what torments I shall be exposed when you have left me.’ The tears, which ran in streams from her eyes, and the convulsive throbs of her bosom, prevented her further utterance. The Prince of Persia wished to make a reply, but he had not sufficient strength of mind. His own grief, added to what he saw Schemselnihar suffer, took from him all power of speech.

“Ebn Thaher, whose only object was to get out of the palace, was obliged to console them, and beg them to have a little patience. At this moment the confidential slave broke in upon them. ‘O lady,’ she cried, ‘you have no time to lose; the eunuchs are beginning to assemble, and you know from this that the caliph will very soon be here.’ ‘Oh, Heavens!’ exclaimed the favourite, ‘how cruel is the separation! Hasten,’ she cried to the slave, ‘and conduct them to the gallery which on one side looks towards the garden, and on the other towards the Tigris; and when night shall have hidden the face of the earth in darkness, let them out of the gate that is at the back of the palace, that they may retire in perfect safety.’ At these words she embraced the Prince of Persia, without having the power of saying another word; and then went to meet the caliph, with her mind in a disordered state, as may easily be imagined.

“In the meantime the confidential slave conducted the prince and Ebn Thaher to the gallery whither Schemselnihar had ordered her to repair. As soon as she had introduced them into it she left them there, and went out, shutting the doors after her, after she had first assured them that they had nothing to fear, and that she would come at the proper time and let them out.

“The slave, however, was no sooner gone, than both the prince and Ebn Thaher forgot the assurances she had given them that they had no cause for alarm. They examined the gallery all round; and were extremely frightened when they failed to discover a single outlet by which they could escape, in case the caliph or any of his officers should by any chance happen to come there.

“A sudden light, which they saw through the blinds, in the direction of the garden, induced them to go and examine from whence it came. It was caused by the flames of a hundred flambeaux of white wax, which a hundred young eunuchs carried in their hands. These eunuchs were followed by more than their own number of others who were older. All of them formed part of the guard continually on duty at the apartments of the ladies of the caliph’s household. They were dressed and armed with scimitars, in the same way as those I have before mentioned. The caliph himself walked after these, with Mesrour, the chief of the eunuchs, on his right hand, and Vassif, the second in command, on his left.

“Schemselnihar waited for the caliph at the entrance of one of the walks. She was accompanied by twenty very beautiful young women, who wore necklaces and ear-rings made of large diamonds, and whose heads were also profusely ornamented with gems of the same description. They all sang to the sound of their instruments, and gave a most delightful concert. When the favourite saw the caliph appear, she advanced towards him, and prostrated herself at his feet. But at the very instant she thus did homage to her master, she said to herself, ‘If your mournful eyes, O Prince of Persia, were witness to what I am now compelled to do, you would be able to judge of the hardness of my lot. It is before you alone that I would wish thus to humble myself; my heart would not then feel the least repugnance.’

“The caliph was delighted to see Schemselnihar. ‘Rise, beautiful lady,’ he cried, as he approached her, ‘and come near to me. I have felt myself but ill at ease while I have been deprived for so long a time of the pleasure of beholding you.’ So saying, he took her by the hand, and continuing to address the most kindly and obliging words to her, he seated himself on the throne of silver which she had ordered to be brought. Thereupon she took her seat before him; and the other twenty women formed an entire circle round them, sitting down on cushions; while the hundred young eunuchs who carried the flambeaux, dispersed themselves at certain distances from each other all over the garden; and the caliph in the meantime at his ease enjoyed the freshness of the evening air.

“When the caliph had taken his seat, he looked round him, and observed with great satisfaction that the garden was illuminated with a multitude of other lights besides those which the eunuchs carried. He noticed, however, that the saloon was shut up: at this he seemed surprised, and asked the reason of this strange appearance. It had been done, in fact, on purpose to astonish him; for he had no sooner spoken than all the windows at once suddenly opened, and he saw the hall lighted up both within side and without with more complete and magnificent illuminations than he had ever yet beheld. ‘Charming Schemselnihar,” he cried at this sight, ‘I understand your meaning: you wish me to acknowledge that the night may be made as beautiful as the day. And after what I now see I cannot deny it.’

“Let us now return to the Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher, whom we left shut up in the gallery. Although he felt himself in a very disagreeable situation, the latter could not help admiring everything that passed, and wondered at the splendour of which he was a spectator. ‘I am not a young man,’ he cried, ‘and have in the course of my life beheld many beautiful sights; but I really think I never saw any spectacle so surprising or grand as this. Nothing that has been related, even of enchanted palaces, at all equals the glories we have now before our eyes. What a profusion of magnificence and riches!’

“But none of these brilliant sights seemed to have any effect upon the Prince of Persia, who derived no pleasure from them like Ebn Thaher did. His eyes were only intent upon watching Schemselnihar, and the presence of the sultan plunged him into the greatest affliction. ‘Dear Ebn Thaher,’ he cried, ‘would to Heaven I had a mind sufficiently at ease to be interested, like yourself, in everything that is splendid and admirable around us. But, alas! I am in a very different state of mind; and all things serve but to increase my torment. How can I possibly see the caliph alone with her I adore, and not die in despair? Ought an affection, so tender and indelible as mine, to be disturbed by so powerful a rival? Heavens! how extraordinary and cruel is my destiny! Not an instant ago I thought myself the happiest and most fortunate lover in the world; and at this moment I feel a pang at my heart that will cause my death. No, dear Ebn Thaher, I cannot resist it. My patience is worn out; my misfortune completely overwhelms me, and my courage sinks under it.’ As he spoke these last words he observed something going on the garden which obliged him to be silent and give his attention.

“The caliph had commanded one of the women who stood around Schemselnihar that was near to take her lute and sing. The words she sang were very tender and impassioned. The caliph felt assured that she sang them by order of Schemselnihar, who had often given him similar proofs of her affection, and he accordingly interpreted them in favour of himself. But at that moment any compliment to the caliph was very far from the intention of Schemselnihar. She in her heart applied the words to her dear Ali Ebn Becar, the Prince of Persia; and the misery she felt at having, in his stead, a master whose presence she could not endure, had such an effect upon her that she fainted. She fell back in her chair, and would have sunk on the ground if some of her women had not quickly run to her assistance. They carried her away, and bore her into the saloon.

“Astonished at this incident, Ebn Thaher, who was in the gallery, turned his head towards the Prince of Persia, and was yet more surprised when, instead of seeing him leaning against the blind, and looking out into the darkness as he himself had been doing, he found the prince stretched motionless at his feet. By this display of emotion, he judged of the strength of the Prince of Persia’s love for Schemselnihar, and could not help wondering at this strange effect of sympathy, which distressed him the more on account of the place they were then in. He did all he could to recover the prince, but without success. Ebn Thaher was in this embarrassing situation when the confidante of Schemselnihar opened the door of the gallery, and ran in quite out of breath, and like one who did not know what course to take. ‘Come instantly,’ cried she, ‘that I may let you out. Everything here is in such confusion that I believe our very lives are in jeopardy.’ ‘Alas!’ replied Ebn Thaher, in a tone which bespoke his grief, ‘how can we depart? Come hither, and see what a state the Prince of Persia is in.’ When the slave saw that he had fainted, she ran immediately to get some water, without losing time in conversation, and returned in a few moments.

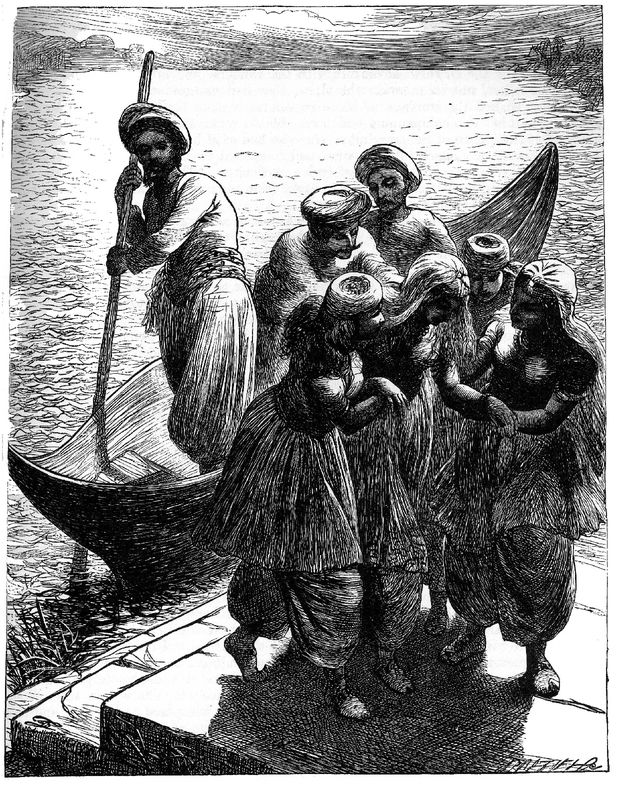

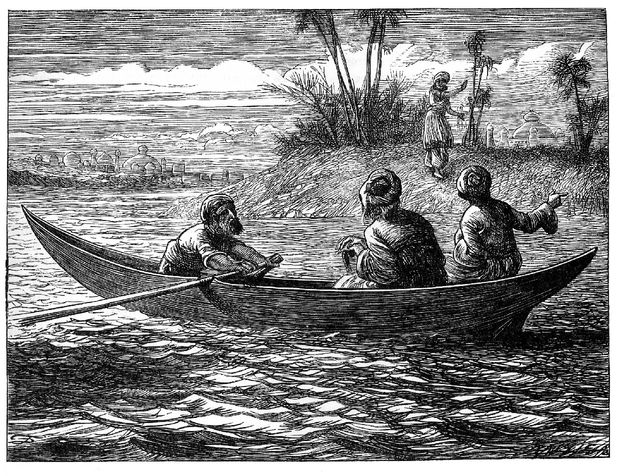

“After they had sprinkled water on his face, the Prince of Persia at length began to recover. When Ebn Thaher saw symptoms of returning animation, he said to him, ‘Prince, we both run a great risk of losing our lives by remaining here any longer, therefore make an effort, and let us fly as quickly as possible.’ The prince was so weak that he could not rise without assistance. Ebn Thaher and the confidante gave him their hands, and, supporting him on each side, they came to a little iron gate, which led towards the Tigris. They went out by this gate, and proceeded to the edge of a small canal communicating with the river. The confidential slave clapped her hands, and instantly there appeared a little boat rowed by one man, and it came towards them. Ali Ebn Becar and his companion embarked in it, and the slave remained on the bank of the canal. As soon as the prince was seated in the boat, he stretched out one hand towards the palace, and placing the other on his heart, cried in a feeble voice, ‘Dear object of my soul, receive from this hand the pledge of my faith, while with my other I assure you that my heart will ever cherish the flame with which it now burns.’

“The boatman rowed with all his strength, and the slave walked on the bank of the canal to accompany the Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher till the boat was floating in the current of the Tigris. Then, as she could not go any farther, she took her leave of them, and returned.

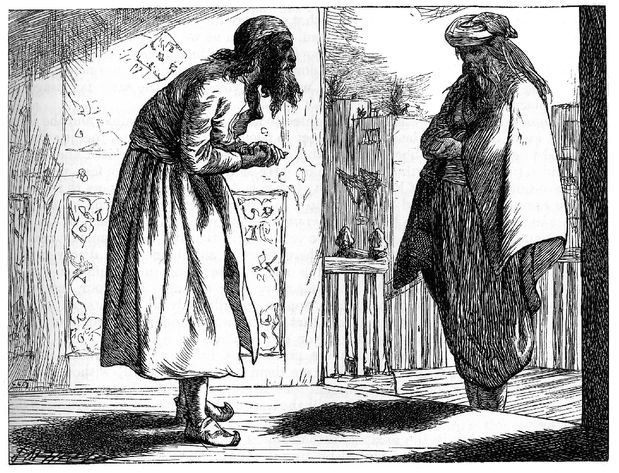

The Prince of Persia and Ebn Thaher escape from the palace.

“The Prince of Persia continued extremely weak. Ebn Thaher said all he could do console him, and exhorted him to take courage. ‘Remember,’ said he, ‘that when we disembark we shall still have a long way to go before we arrive at my house; for, considering the state in which you now are, to conduct you to yours, which is so much farther, at this hour, would, I think, be very imprudent. We might also run a risk of meeting the watch.’ They at length got out of the boat, but the prince was so feeble that he could not walk; and this very much increased Ebn Thaher’s embarrassment. He recollected that he had a friend in the neighbourhood, and, with great difficulty, led the prince to that friend’s house. Ebn Thaher’s friend received his visitors very cordially, and when he had made them sit down, he asked them from whence they came at that late hour. Ebn Thaher replied, ‘I heard this evening that a man who owes me a considerable sum of money intended to set out on a very long journey; I therefore immediately went in search of him, and on my way I met this young lord whom you see, and to whom I am under many and great obligations; as he knows my debtor, he did me the favour to accompany me. We had some difficulty in gaining our point, and inducing my debtor to behave with justice towards me. However, at last we succeeded, and this is the reason why we are wandering so late in the city. As we were returning this young lord, for whom I have the utmost regard, felt himself suddenly seized with illness at a few paces from your house; and this induced me to take the liberty of knocking at your door. I flattered myself that you would have the goodness to give us a lodging for this night.’

“The friend of Ebn Thaher was easily imposed on by this fable. He told them they were welcome, and offered the Prince of Persia, whom he did not know, every assistance in his power. But Ebn Thaher, taking upon himself to answer for the prince, said that his friend’s illness was of a nature that required no remedy but repose. The druggist’s friend also understood by this speech that both his guests wanted rest. He therefore conducted them to an apartment, where he left them alone.

“The Prince of Persia soon fell asleep. But his repose was disturbed by the most distressing dreams, representing Schemselnihar fainting at the feet of the caliph, and thus his affliction did not at all subside. Ebn Thaher, who was excessively impatient to get to his own house, for he doubted not that his family were in the utmost distress, because he made it a rule never to sleep from home, got up and departed very early, after taking leave of his friend, who had risen by daybreak to go to early prayers. They at length arrived at Ebn Thaher’s house. The Prince of Persia, who had exerted himself very much to walk so far, threw himself upon a sofa, feeling as much fatigued as if he had accomplished a long journey. As he was not in a fit state to go home, Ebn Thaher ordered an apartment to be prepared for him; and that none of the prince’s people might be uneasy about their master, he sent to inform them where he was. In the meantime he begged the prince to endeavour to make his mind easy, and order everything about him as he pleased. The Prince of Persia replied: ‘I accept with pleasure the obliging offers you make; but that I may not be any embarrassment to you, I entreat you to attend to your own affairs as if I were not with you. I cannot think of staying here a moment if my presence is to be any restraint upon you.’

“As soon as Ebn Thaher had time to collect his thoughts, he informed his family of everything that had occurred in the palace of Schemselnihar, and finished his recital by returning thanks to God for having delivered him from the danger he had escaped. The principal servants of the Prince of Persia came to receive their orders from him at Ebn Thaher’s; and soon afterwards several of his friends arrived who had been informed of his indisposition. His friends passed the greater part of the day with him; and although their conversation could not entirely banish the sorrowful reflections which occasioned his illness, at least it was thus far of advantage, that it gave him some relaxation.

“Towards the close of the day the prince wished to take his leave of Ebn Thaher; but this faithful friend found him still so weak that he induced him to remain till the following morning. In the meantime, to dissipate his gloom, he gave him in the evening a concert of vocal and instrumental music; but this only served to recall to the prince’s memory the beautiful strains he had enjoyed the preceding night, and increased his grief instead of assuaging it; so that the next day his indisposition seemed to be augmented. Finding this to be the case, Ebn Thaher no longer opposed the prince’s wish to return to his own house. He undertook the care of having him conveyed thither, and also accompanied him; and when he found himself alone with the prince in his apartment, he represented to him in strong terms the necessity of making one great effort to overcome a passion which could not terminate happily either for him or the favourite. ‘Alas! dear Ebn Thaher,’ cried the prince, ‘it is easy for you to give this advice; but how difficult a task for me to follow it! I see and confess the importance of your words, without being able to profit by them. I have already said it: the love I have for Schemselnihar will accompany me to the grave.’ When Ebn Thaher perceived that he could make no impression on the mind of the prince, he took his leave with the intention of retiring, but the prince would not let him depart. ‘Kind Ebn Thaher,’ said he to the druggist, ‘though I have declared to you that it is not in my power to follow your prudent counsel, I entreat you not to be angry with me, nor to desist on that account from giving me proofs of your friendship. You could not do me a greater service than by informing me of the fate of my beloved Schemselnihar, if you should hear any tidings of her. The uncertainty I am under respecting her situation, and the dreadful apprehensions I feel on account of her fainting, cause the continuance of the languor and illness for which you reproved me so bitterly.’ ‘My lord,’ replied Ebn Thaher, ‘you may surely hope that her fainting has not produced any bad consequences, and that her confidential slave will shortly come to acquaint me how the affair terminated. As soon as I know the particulars, I will not fail to come and communicate them to you.’

“Ebn Thaher left the prince with this hope, and returned home; where he waited all the rest of the day in expectation of the arrival of Schemselnihar’s favourite slave; but he waited vainly. She did not make her appearance even on the morrow. The anxiety he felt to learn the state of the prince’s health did not allow him to remain any longer without seeing his friend; and he went to him with the design of exhorting him to have patience. He found him stretched upon the bed, and quite as ill as before. Around his couch stood his friends, and several physicians, who were exerting all their professional skill to endeavour to discover the cause of his disease. As soon as he perceived Ebn Thaher, he cast a smiling look on him, which denoted two things: one, that he was rejoiced to see him; the other, that his physicians were deceived in their conjectures on his disease, the cause of which they could not guess.

“The physicians and the friends retired, one after the other, so that Ebn Thaher remained alone with the sick prince. He approached his bed, to inquire how he had felt since he last saw him. ‘I must own to you,’ replied the Prince of Persia, ‘that my love, which every day acquires increased strength, and the uncertainty of the destiny of the lovely Schemselnihar, heighten my disease every moment, and reduce me to a state which causes much grief to my relations and friends, and baffles the skill of the physicians, who cannot understand it. You little imagine,’ added he, ‘how much I suffer at seeing so many people, who constantly importune me, and whom I cannot dismiss without seeming ungrateful. You are the only one whose company affords me any comfort; but do not disguise anything from me, I conjure you. What news do you bring of Schemselnihar? Have you seen her favourite slave?’ Ebn Thaher answered that he had not seen the slave of whom his friend spoke: and he had no sooner communicated this sorrowful intelligence to the prince, than the tears came in the young man’s eyes: he could make no reply, for his heart was full. ‘Prince,’ resumed Ebn Thaher, ‘allow me to say that you are too ingenious in tormenting yourself. In the name of Allah, dry your tears; some of your servants might come in at this moment, and you are well aware how cautious you ought to be to conceal your sentiments, which might be discovered from the emotion you are exhibiting.’ But all the remonstrances of this judicious counsellor were ineffectual to stop the prince’s tears, which he could not restrain. ‘Wise Ebn Thaher,’ cried he, when he had regained the power of speech, ‘I can prevent my tongue from revealing the secret of my heart, but I have no power over my tears, while my heart is distracted with anxiety for Schemselnihar. If this adorable and only delight of my soul were no longer in this world, I should not survive her one moment.’ ‘Do not harbour so afflicting a thought,’ replied Ebn Thaher; ‘Schemsel nihar still lives; you must not doubt it. If she has not sent you any account of herself, it is probably because she has not been able to find an opportunity, and I hope this day will not pass without your receiving some intelligence of her.’ He added many other consoling speeches, and then took his leave.

“Ebn Thaher had scarcely returned to his house, when the favourite slave of Schemselnihar arrived. She had a sorrowful air, which prepared him to hear news of which he conceived an unfavourable presage. He inquired after her mistress. ‘First,’ said she, ‘give me some intelligence of yourselves, for I was in great anxiety on your account, seeing the state in which the Prince of Persia appeared to be when you departed together.’ Ebn Thaher related to her all she wished to know; and when he had concluded his narrative, the slave spoke in the following words: ‘If the Prince of Persia suffers on my mistress’s account, she does not endure less pain for him. After I had quitted you,’ continued she, ‘I returned to the saloon, where I found Schemselnihar, who had not yet recovered from her fainting fit, notwithstanding all the remedies that had been applied. The caliph was seated by her side, showing every symptom of real grief. He inquired of all the women, and of me in particular, if we had any knowledge of the cause of her indisposition; but we all kept the secret, and told him quite the contrary to what we knew to be the fact. We were all in tears at the sight of her sufferings, and tried every means that we thought might relieve her. It was quite midnight when she came to herself. The caliph, who had waited patiently until now, showed great joy, and asked Schemselnihar what had caused this illness. As soon as she heard the caliph’s voice she made an effort to sit up, and kissed his feet before he had time to prevent her. ‘O my lord,’ she said, ‘I ought to complain of Heaven for not having suffered me to die at your majesty’s feet, that I might thus convince you how sincerely I am penetrated by the sense of all your goodness to me.’

“ ‘I am convinced that you love me,’ replied the caliph, ‘but I command you to take care of yourself for my sake. You have probably made some exertion to-day, which has been the cause of this illness; you must be more careful, and I beg you to avoid a repetition of anything that may be injurious. I am happy to see that you are partly recovered, and I advise you to pass the night here, instead of returning to your apartment, for moving might be hurtful to you.’ He then ordered some wine to be brought, of which he made her take a small quantity to give her strength, and he then took his leave of her, and retired to his chamber.

“ ‘So soon as the caliph was gone, my mistress made signs to me to approach her. She anxiously inquired after you. I assured her that you had long since quitted the palace, and set her mind at ease on that subject. I took care not to mention the fainting of the Prince of Persia, for fear she should relapse into the state from which we had with so much difficulty recovered her. But my precaution was useless, as you will shortly hear. ‘O prince,’ cried Schemselnihar, ‘from this time I renounce all pleasures so long as my eyes shall be deprived of the gratification of beholding you: if I understand your heart, I am but following your example. You will not cease your tears until you are restored to me; and it is but just that I should weep and lament until you are given back to my prayers.’ With these words, which she pronounced in a manner that denoted the violence of her love, she fainted a second time in my arms.

“ ‘It was long before my companions and I could recall her to her senses. At length her consciousness returned. I then said to her, ‘Are you resolved, lady, to suffer yourself to die, and to make us die with you? I conjure you in the name of the Prince of Persia, in whom you are so interested, to endeavour to preserve your life. I entreat you to hear me, and to make those efforts which you owe to yourself, to your love for the prince, and to our attachment to you.’ ‘I thank you sincerely,’ returned she, ‘for your care, your attention, and your advice. But, alas! how can they be serviceable to me? We are not permitted to flatter ourselves with any hope; and it is only in the bosom of the grave that we may expect a respite from our torments.’

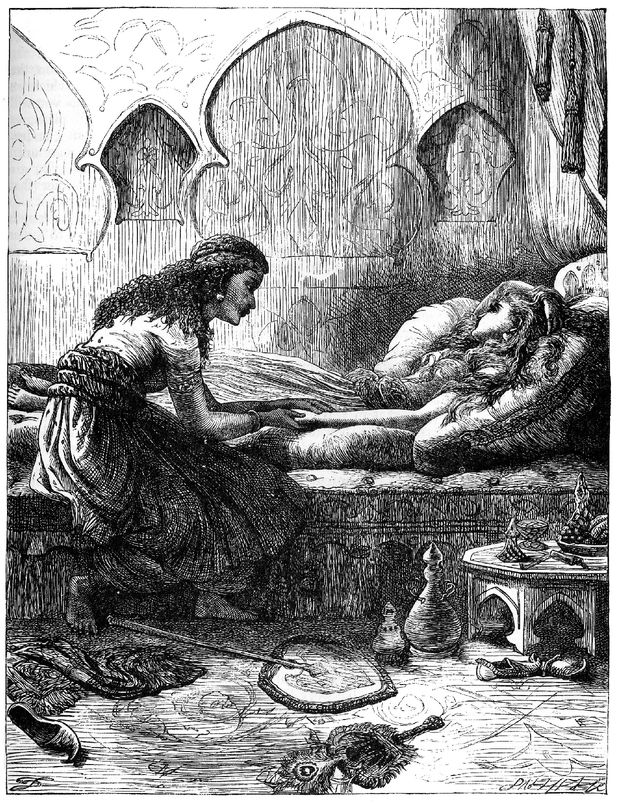

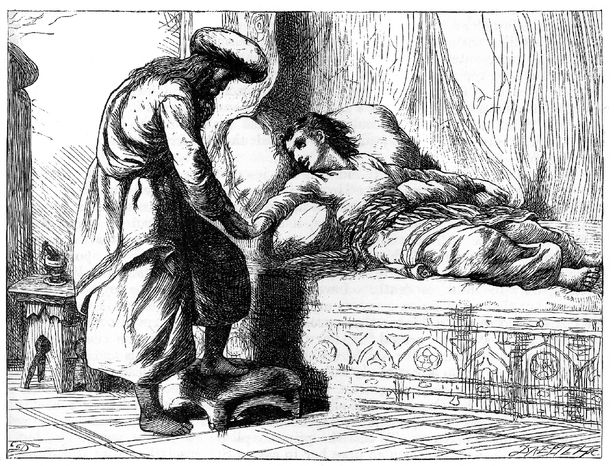

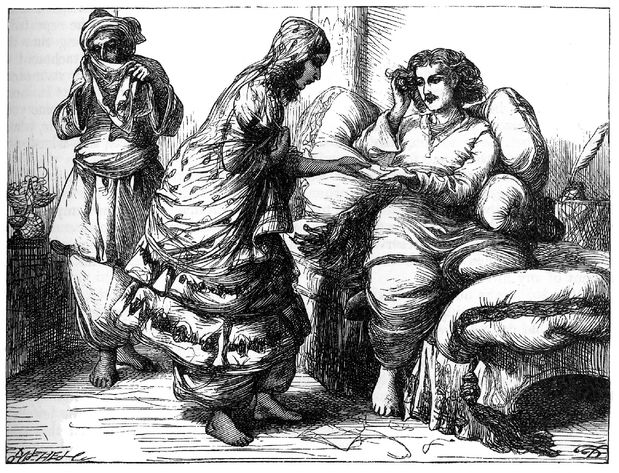

Schemselnihar’s distress.

“ ‘One of my companions wished to divert our lady’s melancholy ideas by singing a little air to her lute; but Schemselnihar desired her to be silent, and ordered her, with the rest, to quit the room. She kept only me to spend the night with her. Heavens! what a night it was! She passed it in tears and lamentations, calling continually on the name of the Prince of Persia. She bewailed the cruelty of her fate, which had thus destined her for the caliph, whom she could not love, and had deprived her of all hope of being united to the Prince of Persia, of whom she was so passionately enamoured.

“ ‘The next day, as it was not convenient for her to remain in the saloon, I assisted to remove her into her own apartment. So soon as she was installed there all the physicians of the palace came to see her, by order of the caliph; and it was not long before he himself made his appearance. The remedies prescribed by the physicians for Schemselnihar had no effect; for these men were ignorant of the cause of her illness; and the restraint she felt in the presence of the caliph increased her sufferings. She has, however, enjoyed a little rest last night, and as soon as she awoke, she charged me to come to your house to obtain some intelligence of the Prince of Persia.’ ‘I have already informed you of the state he is in,’ replied Ebn Thaher; ‘therefore return to your mistress, and assure her that the Prince of Persia expected to hear from her with as much impatience as she could feel to hear news of him. Exhort her especially to moderate and conquer her feelings, lest some word escape her lips in the presence of the caliph, which may prove the destruction of us all.’ ‘As for me,’ returned the slave, ‘I am in constant apprehension, for she has very little command over herself. I took the liberty of telling her what I thought on that subject, and I am certain she will not take it amiss if I give her your message also.’

“Ebn Thaher, who had but just left the Prince of Persia, did not judge it proper to return again so soon. He had, moreover, to transact some important business which would keep him at home; thus he did not see his friend again till the close of day. The prince was alone, and was no better than he had been in the morning. ‘Ebn Thaher,’ said he, when he saw the druggist enter the room, ‘you have, no doubt, many friends; but those friends do not know your worth as I know it; for I have witnessed the zeal, the care, and the pains you take when an opportunity offers to do your friend a service. I am quite confused at the thought of all you do for me. You show so much friendship and affection, that I shall never be able to repay you for your goodness.’

“ ‘Prince,’ replied Ebn Thaher, ‘let us not speak on that subject. I am ready not only to lose one of my eyes to preserve one of yours, but even to sacrifice my life for you. But this is not the business I am come upon: I came to tell you that Schemselnihar sent her confidential slave to me, to inquire after your health, and at the same time to give you some information respecting herself. You may imagine that the message I sent must confirm her belief of the excess of your love for her mistress, and of the constancy with which you adore her.’ Ebn Thaher then gave the prince an exact detail of everything the slave had told him. The prince heard the account with all the different emotions of fear, jealousy, tenderness, and compassion, which such a relation was likely to inspire; and during the progress of the narrative, he made on each circumstance of an afflicting or consoling nature such reflections as so passionate a lover could be capable of.

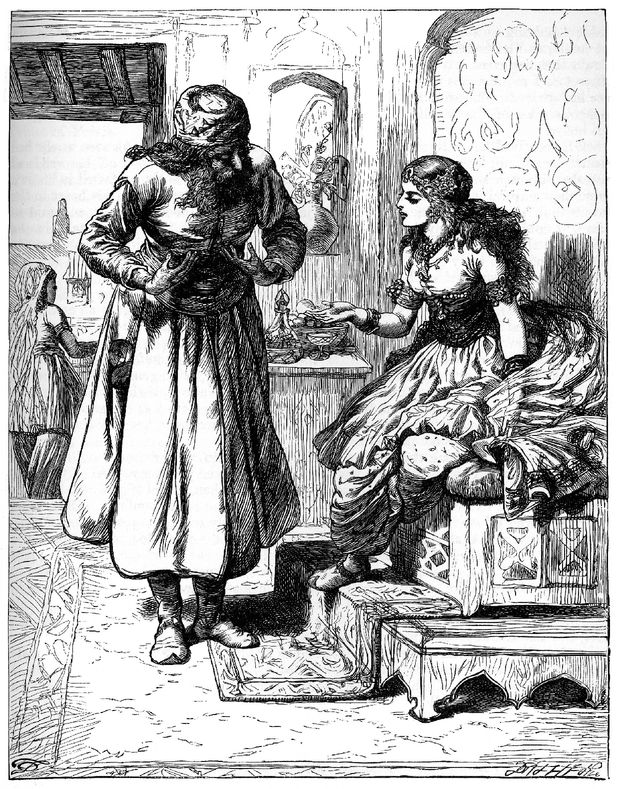

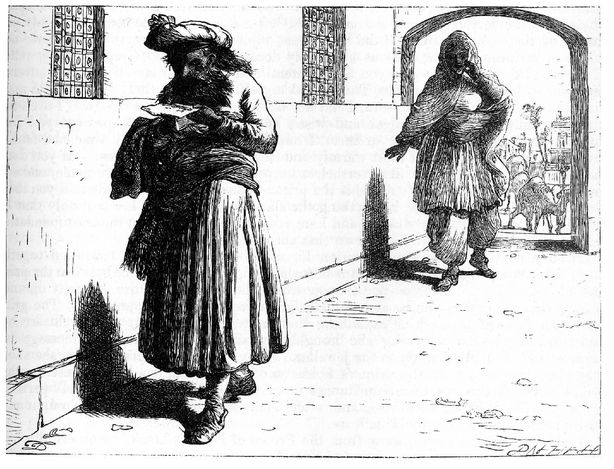

“The conversation had lasted so long that the night was now far advanced. Accordingly the Prince of Persia made Ebn Thaher remain at his house. The next morning, as this faithful friend was returning home, he saw a woman coming towards him, whom he soon recognised to be the confidential slave of Schemselnihar. She came up to him and said, ‘My mistress salutes you, and I come from her to beg you to deliver this letter to the Prince of Persia.’ The friendly Ebn Thaher took the letter, and returned to the prince, accompanied by Schemselnihar’s attendant.

“When they came to the prince’s house, Ebn Thaher begged her to remain a few minutes in the antechamber and wait for him. As soon as the prince saw his friend, he anxiously inquired what news he had to tell. ‘The best you can possibly wish,’ replied Ebn Thaher: ‘you are beloved as tenderly as you love. Schemselnihar’s confidential slave is in your antechamber; she brings you a letter from your mistress, and only waits your orders to appear before you.’ ‘Let her come in!’ cried the prince in a transport of joy. And saying this he raised himself in his bed to receive her.

“As the attendants of the prince had left the room when Ebn Thaher entered it, that he might be alone with their master, Ebn Thaher went to open the door himself, and desired the confidante to come in. The prince recollected her, and received her with great distinction. ‘My lord,’ said she, ‘I know all the pains you have suffered since I had the honour of conducting you to the boat which waited to take you home; but I hope that the letter I bring you will contribute to your recovery.’ She then presented to him the letter. He took it and after having kissed it several times, he opened it, and read the following words:—

“ ‘Schemselnihar to Ali Ebn Becar, Prince of Persia.

“ ‘The person who will deliver this letter to you will give you an account of me better than I myself can give; for all outward things are nothing to me, since I ceased beholding you. Deprived of your presence, I seek to continue the illusion, and converse with you by means of these ill-formed lines; and this occupation affords me some pleasure, while I am debarred from the happiness of speaking to you

“ ‘I have been told that patience is the remedy for all evils; yet the ills I suffer are increased rather than relieved by it. Although your image is indelibly engraven on my heart, my eyes wish again to behold you in person; and their sight will forsake them if they remain longer deprived of that gratification. Dare I flatter myself that yours experience the same impatience to see me? Yes, I may; they have sufficiently proved it to me by their tender glances. Happy would Schemselnihar be, happy would you be, O prince, if my wishes, which are the counterpart of yours, were not opposed by insurmountable obstacles! These obstacles occasion me a grief that is the sharper for being the cause of sorrow to you.

“ ‘These sentiments which my fingers trace, and in the expression of which I feel such inconceivable consolation that I cannot repeat them too often, proceed from the bottom of my heart—from that incurable wound you have made in it; a wound which I bless a thousand times, notwithstanding the cruel sufferings I endure in your absence. I should care little for all the obstacles that oppose our love, were I only permitted to see you occasionally without restraint. I should then enjoy your society; and what more could I desire?

“ ‘Do not imagine that my words convey more than I feel. Alas! whatever expressions I may use, I shall still leave unsaid much more than I can ever say. My eyes, which never cease looking for you, and incessantly weep till they shall behold you again; my afflicted heart, which seeks but you; my sighs, which pour from my lips whenever I think of you, and I am thinking of you continually; my memory, which never reflects any object but my beloved prince; the complaints I utter to Heaven of the rigour of my fate; my melancholy, my uneasiness, my sufferings, from which I have had no respite since you were torn from my gaze, are all sufficient pledges of the truth of what I write.

“ ‘Am I not truly unfortunate to be born to love—to love, without indulging the hope that the object of my affections will ever be mine? This dreadful reflection overpowers me to such a degree that I should die were I not convinced that you love me. But this sweet consolation counteracts my despair, and attaches me to life. Tell me that you love me still. I will preserve your letter as a treasure of price: I will read it a thousand times a day; and I shall then bear my sorrows with less impatience. I pray that Heaven may no longer be angry with us, but may grant us an opportunity of revealing to each other, without restraint, the tender affection we feel, and of mutually declaring that we will never cease to love. Farewell.

“ ‘I salute Ebn Thaher, to whom we are both under so many obligations. ’

“ ‘The Prince of Persia was not satisfied with reading this letter only once. He thought he had not bestowed sufficient attention on it; he read it again more deliberately, and while thus engaged he frequently uttered deep sighs, and as frequently wept. He then would burst into transports of joy and tenderness, according to the different emotions he experienced from the contents of the letter. In short, he could not withdraw his eyes from the characters traced by that beloved hand, and he was going to read the writing a third time, when Ebn Thaher represented to him that the slave had no time to lose, and that he must prepare an answer. ‘Alas!’ cried the prince, ‘how can I reply to so obliging and kind a letter? In what terms shall I describe the anguish of my soul? My mind is agitated by a thousand distressing thoughts, and my sentiments are obliterated before I have time to express them by others, which in their turn are erased as soon as formed. While my bodily frame shares the agitation of my mind, how shall I be able to hold the paper and guide the reed to form the letters? ’

“Saying this, he drew from a little writing case, which was near him, some paper, a cut reed, and an ink-horn; but before he began to write he gave the letter of Schemselnihar to Ebn Thaher, and begged him to hold it open before him, that, by occasionally casting his eyes over it as he wrote, he might be better enabled to answer it. He took up the writing-cane to begin; but the tears, which flowed from his eyes on the paper, frequently obliged him to stop to allow them a free course. He at length finished his letter, and gave it to Ebn Thaher, with these words: ‘Do me the favour to read it, and see if the agitation of my spirits has allowed me to write a proper answer.’ Ebn Thaher took the paper, and read as follows: —

“ ‘The Prince of Persia to Schemselnihar.

“ ‘I was sunk in the deepest affliction when your letter was delivered into my hands. At the sight of the words traced by your pen, I was transported with a joy I cannot express; but on reading the lines which your beautiful hand had sent to comfort me, my eyes were sensible of greater pleasure than that which they lost when yours so suddenly closed on the evening when you fell senseless at my rival’s feet. The words contained in your beloved letter, are so many luminous rays, that enliven the obscurity in which my soul was wrapped. They convince me how much you suffer for me, and also prove that you sympathise with the anguish I endure for you, and thus console me in my pain. At one moment they cause my tears to flow in abundant streams; at another they inflame my heart with an inextinguishable fire, which supports it, and prevents my expiring with grief. I have not tasted one instant’s repose since our too cruel separation. Your letter alone afforded me some relief from my misery. I preserved an uninterrupted silence till it was placed in my hands; but that has restored to me the power of speech. I was wrapped in the most profound melancholy; but that has inspired me with joy, which instantly proclaimed itself in my eyes and countenance. My surprise at receiving a favour so unmerited was so great, that I knew not how to express myself, or in what words to testify my gratitude. I have kissed it a thousand times, as the precious pledge of your goodness; I read it again and again, till I was quite lost in the excess of my happiness. You tell me to say that I love you still; alas! had my love for you been less passionate, less tender than is the passion that fills my whole soul, could I have done otherwise than adore you, after all the proofs you give me of the strength and endurance of your affection? Yes, I love you, my dearest life; and to the end of my existence shall glory in the pure flame which you have kindled in my heart. I will never complain of the vivid fire which consumes my being; and however rigorous may be the pains which your absence occasions, I will support them with constancy and firmness, encouraged by the hope of beholding you again. Would to Heaven I could see you to-day, and that, instead of sending you this letter, I might be permitted to present myself before you, that I might die for love of you. My tears prevent me from continuing to write. Farewell.’

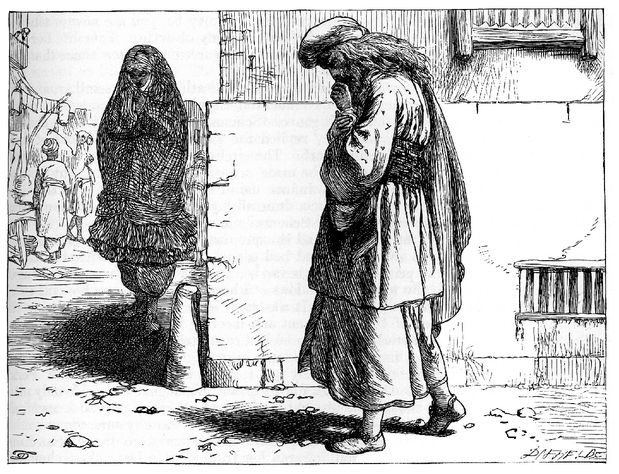

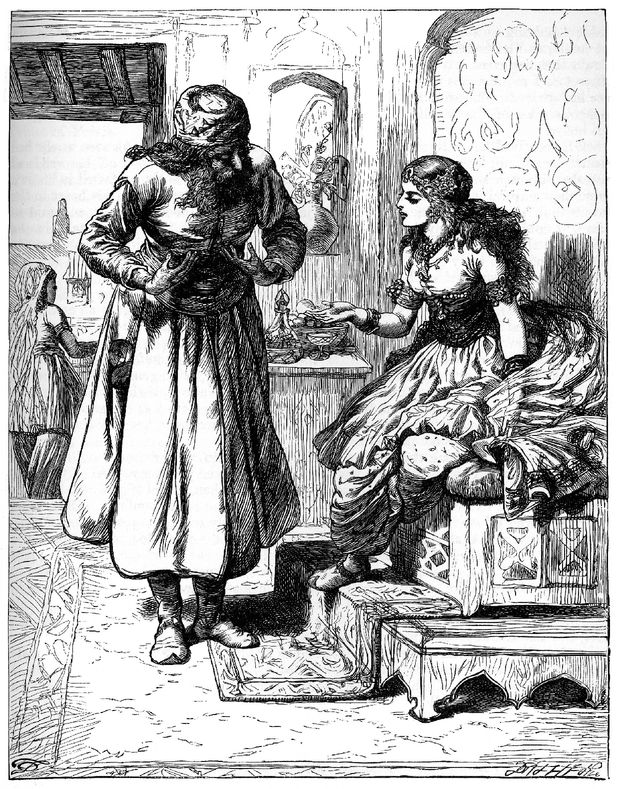

The Prince sends his letter to Schemselnihar.

“Ebn Thaher could not read the last lines without himself shedding tears. He returned the letter to the prince, assuring him it needed no correction. The prince folded it up, and when he had sealed it, he said to the confidential slave, who had retired to the end of the apartment: ‘I beg you to approach. This is the answer I have written to the letter of your dear mistress. I entreat you to take it to her, and to salute her from me.’ The slave took the letter, and retired with Ebn Thaher, who, after he had walked some distance with her, left her and returned to his house, where he began to make serious reflections on the unhappy affair in which he found himself so unfortunately and deeply engaged. He considered that the Prince of Persia and Schemselnihar, notwithstanding the strong interest they had in concealing their sentiments, behaved with so little discretion that their love could not long remain a secret. He drew from this reflection all the unfavourable conclusions which must naturally suggest themselves to a man of good sense. ‘If Schemselnihar,’ thought he, ‘were not a lady of such high rank, I would exert myself to the utmost of my ability to make her and her lover happy; but she is the favourite of the caliph, and no man can aspire to become the possessor of one who has gained the affections of our master with impunity. The caliph’s anger will first fall on Schemselnihar; the prince will assuredly lose his life; and I shall be involved in his misfortune. But I have my honour, my peace of mind, my family, and my property to take care of; I must, then, while it is in my power, endeavour to extricate myself from the perils in which I find myself involved.’

“Ebn Thaher’s mind was occupied with thoughts of this nature for the whole of that day. The following morning he went to the Prince of Persia with the intention of making one last effort to induce him to conquer his unfortunate passion. In vain he repeatedly urged upon the prince all the arguments he had already employed, declaring that the prince would do much better to exert all his courage to overcome this attachment to Schemselnihar; that he should not suffer himself to be led away to destruction by its means; and that his love for her was dangerous to himself, as his rival was so powerful. ‘In short, my lord,’ added he, ‘if you will take my advice, you will endeavour to overcome your affection; otherwise you run the risk of causing the destruction of Schemselnihar, whose life ought to be dearer to you than your own. I give you this counsel as a friend, and some day you will thank me for it.’

“The prince listened to Ebn Thaher with evident impatience, though he allowed him to finish what he wished to say; but when the druggist had concluded he said: ‘Ebn Thaher, do you suppose that I can cease to love Schemselnihar, who returns my affection with so much tenderness? She does not hesitate to expose her life for me, and can you imagine that the care of preserving mine should occupy me a single moment? No; whatever misfortunes may be the consequence, I will love Schemselnihar to the last moment of my life.’

“Offended at the obstinacy of the prince, Ebn Thaher left him abruptly, and returned home, where, recollecting his reflections on the preceding day, he began to consider very seriously what course he should pursue.

“While he was thus lost in thought, a jeweller, an intimate friend of his, came to see him. This jeweller had observed that the confidential slave of Schemselnihar had been with Ebn Thaher more frequently than usual, and that Ebn Thaher himself had been almost incessantly with the Prince of Persia, whose indisposition was known to every one, although the cause was a secret. All this had created some suspicions in the jeweller’s mind. As Ebn Thaher appeared to be absorbed in thought, he supposed that some important affair occasioned this preoccupation; and thinking he had hit on the cause, he asked him what business the slave of Schemselnihar had with him. Ebn Thaher was somewhat confused at this question; but not choosing to confess the truth, he replied, that it was only on a trifling errand that she came to him so often. ‘You do not speak sincerely,’ resumed the jeweller; ‘and by your dissimulation you will make me suspect that this trifle is of a more important nature than I had at first supposed. ’