Chapter 5

Marie’s Discovery

For the next few years, Marie kept studying. At the same time, she kept her job doing research in magnetism.

Meanwhile, she enjoyed her life with Pierre. She bought fresh flowers each week for their apartment. She learned to make jelly from gooseberries. She and Pierre rode their bicycles everywhere. They fell more and more in love.

On September 12, 1897, Marie and Pierre had a baby girl. They named her Irene.

When the baby was a few months old, Pierre’s father moved in with them. His wife had just died, and he was alone. He was willing to help take care of his granddaughter. Marie was glad because she was ready to get back to work.

In those days, women almost never worked outside of the home, but Marie was different. She wanted to do some important research so that she could get her PhD—the degree that would make her a professor.

The only question now was: What should she work on?

Marie and Pierre lived during an exciting time in Paris. The whole world was going crazy for a new scientific discovery—X-rays! The mysterious X-rays had just been discovered two years earlier. Scientists were trying to figure out how X-rays really worked. They soon noticed that X-rays could make some things glow in the dark.

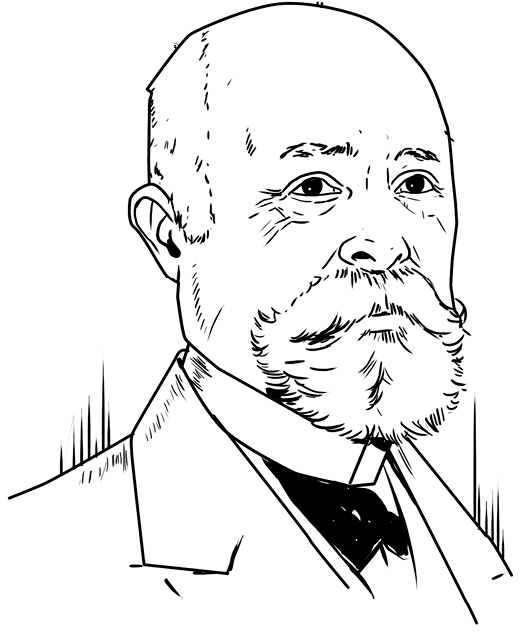

But Marie wanted to study a topic of her own. She decided to study a different kind of rays, called Becquerel rays. These rays were named for Henri Becquerel, the man who discovered them. The rays came from a metal called uranium.

Today we know that uranium is one of several metals that give off powerful radioactive rays. But when Marie Curie started her research, the word radioactive didn’t even exist! No one knew why uranium gave off energy or why it could make things glow in the dark. No one knew then that uranium could be used to make a bomb or a nuclear power plant. Marie’s research was going to open the door for all that knowledge.

Marie set up a laboratory with Pierre’s help. They shared the lab together. It was cold and grungy—just an old storage room in the school where Pierre taught. Marie didn’t mind. Work was all she cared about.

In the lab, Marie used Pierre’s electrometer to measure rays coming from different metals. The tests were very tricky. She had to have very steady hands. No one else could do the tests as well as Marie. Even Becquerel had tried and failed!

At first, Marie tested uranium. Then she tested other metals, including gold and copper. Only the uranium gave off rays.

Then Marie did something brilliant—something that would change science forever. She decided to test a rock called pitchblende. Pitchblende is a rock that contains a lot of uranium. But it has other metals in it, too.

When Marie tested the pitchblende, she found it gave off even more rays than uranium alone! How could that be? Marie figured out the answer. There had to be something else—another metal—mixed into the pitchblende! That other metal, whatever it was, had even more energy than uranium.

Soon Marie realized the truth. She had discovered a new element that the world didn’t know about!

Marie named the new metal after her homeland of Poland. She called it polonium. Then she came up with a word for the rays that the metals gave off. She called it “radioactivity.” It meant that metals like polonium and uranium were able to release energy into the air.

To let the world know about her new discoveries, Marie did what scientists always do: She wrote a report. She wanted to read it to a group of other scientists in the Academy of Sciences in Paris.

The Academy was like a fancy science club for the most important scientists in France. It was hard to join and members had to be voted in.

Marie and Pierre were not members of the Academy. At that time, Pierre couldn’t even get a job teaching at the Sorbonne! Other scientists thought Marie and Pierre weren’t good enough because they didn’t have PhDs from the best colleges. Besides, Marie was a woman. The Academy never let women in. Women weren’t even allowed inside the Academy’s rooms!

Luckily, though, Marie and Pierre had important friends. All the famous scientists in Europe and America knew one another. In April 1898, Marie’s report about her discoveries was read to the Academy by her teacher and friend Gabriel Lippmann.

The scientists were interested in Marie’s report, but no one was amazed—not yet. They weren’t sure she was right. Marie still had to prove that polonium existed. How? By separating it out of the pitchblende.

She had to hurry! Now that the world knew about polonium, other scientists might want to study it. Even Becquerel was interested in Marie’s work. In those days, just like today, scientists tried to help one another, but they also competed with one another to be the first with new ideas.

Becquerel was both a friend and a competitor. He helped Marie get some money for her experiments, but instead of telling Marie about the money, he told Pierre! He treated her like she wasn’t as important as Pierre because she was a woman. Becquerel also took ideas from Marie’s work and tried to do similar experiments himself.

Pierre was totally the opposite. He didn’t like to compete. He simply loved science for its own sake. Marie was the ambitious one. She wanted credit for her discovery. She was determined to be first to prove that her new metal existed.

Marie got to work. She tried to separate the polonium from the pitchblende—but she failed. The amounts of polonium in the pitchblende were too tiny.

While she was trying, though, she stumbled onto something else. Something even better! The pitchblende contained another mysterious metal that was giving off rays. This one was even more radioactive than polonium. What was it?

Marie did a series of tests to find out. After several experiments, she realized she had found another new element! She and Pierre named this new metal radium. Radium was so powerful that even the tiniest amount was a million times more radioactive than uranium.

It was an amazing year for Marie and Pierre. By December 1898, she had discovered two new chemical elements that the world hadn’t known about! Other scientists were beginning to notice her work.

However, some scientists still wanted more proof. They weren’t sure she was right. They wanted to see the radium, and touch it.

Was it even possible to separate the radium from the pitchblende?

Marie was determined to try.