BEGINNINGS: THE EMERGENCE OF CHRISTIANITY AND DENOMINATIONS

The word Christian is used only three times in the New Testament, most importantly in Acts 11:26 (see also Acts 26:28 and 1 Peter 4:16). In Acts 11:26, we are told simply and straightforwardly, “The disciples were called Christians first at Antioch.” This would have happened around AD 42, about a decade after Christ died on the cross and rose from the dead.

Until this time, the followers of Jesus referred to themselves as brothers (Acts 15:1,23), disciples (Acts 9:26), believers (Acts 5:12), and saints (Romans 8:27). Now, in Antioch, they were called Christians.

The term is loaded with significance. Among the ancients, the ian (or ean) ending meant “belonging to the party of.” Herodians belonged to the party of Herod. Caesareans belonged to the party of Caesar. Christians belonged to Christ. And Christians were loyal to Christ, just as the Herodians were loyal to Herod and Caesareans were loyal to Caesar (see Mark 3:6; 12:13).

The name Christian is noteworthy because these followers of Jesus were recognized as members of a separate group. They were distinct from Judaism and from all other religions of the ancient world. We might loosely translate the term Christian, “those belonging to Christ,” “Christ-ones,” or perhaps “Christ-people.” They are ones who follow the Christ.

Those who have studied the culture of Antioch have noted that the Antiochians were well-known for making fun of people. They may have used the word Christian as a term of derision, an appellation of ridicule. Nevertheless, history reveals that by the second century, Christians adopted the title as a badge of honor. They took pride (in a healthy way) in following Jesus. They had a genuine relationship with the living, resurrected Christ, and they were utterly faithful to Him, even in the face of death.

The city of Antioch was a mixture of Jews and Gentiles. People of both backgrounds in this city became followers of Jesus. What brought these believers unity was not their race, culture, or language. Rather, their unity was rooted in the personal relationship each of them had with Jesus. Christianity crosses all cultural and ethnic boundaries.

If a Christian is one who has a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, then Christianity is a movement of people who have personal relationships with Jesus Christ. This may sound simplistic, but from a biblical perspective, this is the proper starting point.

In the New Testament, the early Christians never referred to their collective movement as Christianity, even though they used the term Christian with greater frequency as the movement grew in numbers. By the time of Augustine (AD 354–430), the term Christianity appears to have become a widespread appellation for the Christian movement.

The Birth of the Church

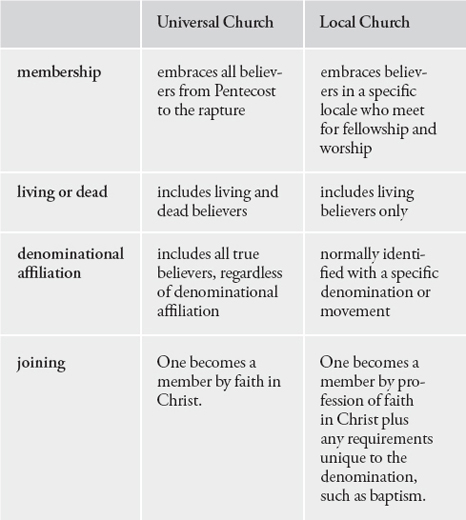

Scripture refers to both the universal church and the local church. The universal church is a company of people who have one Lord and who share together in one gift of salvation in the Lord Jesus Christ (Titus 1:4; Jude 3). It may be defined as the ever enlarging body of born-again believers who comprise the universal body of Christ, over which He reigns as Lord.

Although the members of the church—and members of different denominations—may differ in age, sex, race, wealth, social status, and ability, true believers are all joined together as one people (Galatians 3:28). All of them share in one Spirit and worship one Lord (Ephesians 4:3-6). This body is comprised only of believers in Christ. The way one becomes a member of this universal body is to simply place faith in Christ. If you’re a believer, you’re in!

The word church is translated from the Greek word ekklesia. This Greek word comes from two smaller words. The first is ek, which means “out from among.” The second is klesia, which means “to call.” Combining the two words, ekklesia means “to call out from among.” The church represents those whom God has called out from among the world and from all walks of life. All are welcome in Christ’s church.

Many theologians believe the church did not exist in Old Testament times (I think they are right). Matthew 16:18 cites Jesus as saying, “I will build my church” (future tense). This indicates that when He spoke these words, the church did not yet exist. This is consistent with the Old Testament, which includes no reference to the church. In the New Testament, the church is portrayed as distinct from Israel in such passages as Romans 9:6, 1 Corinthians 10:32, and Hebrews 12:22-24. Therefore, we should not equate the church with believing Israelites in Old Testament times.

Scripture indicates that the universal church was born on the Day of Pentecost (see Acts 2; compare with 1:5; 11:15; 1 Corinthians 12:13). We are told in Ephesians 1:19-20 that the church is built on the foundation of Christ’s resurrection, meaning that the church could not have existed in Old Testament times. The church is thus called a “new man” in Ephesians 2:15.

The one universal church is represented by many local churches scattered throughout the world. For example, we read of a local church in Corinth (1 Corinthians 1:2), and another in Thessalonica (1 Thessalonians 1:1). Only a few local churches existed at first, but due to the missionary efforts of the early Christians, churches soon cropped up around the globe.

The New Testament strongly urges believers to attend local churches. Hebrews 10:25 specifically instructs us not to forsake meeting together. The Christian life as described in Scripture is to be lived in the context of the family of God and not in isolation (Acts 2; Ephesians 3:14-15). Moreover, by attending church, we become equipped for the work of ministry (Ephesians 4:12-16). The Bible knows nothing of a “lone ranger” Christian. As the old proverb says, many logs grouped together burn brightly, but embers that are isolated quickly die out (see Ephesians 2:19; 1 Thessalonians 5:10-11; and 1 Peter 3:8).

The Spread of Christianity

Christianity experienced phenomenal growth following the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. We learn in Acts 1:15 that about 120 Jewish believers in Christ gathered in Jerusalem. A bit later, after Peter’s powerful sermon, 3000 people became believers on the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2:41). The number soon grew to 5000 (Acts 4:4). Soon enough, the Samaritans—whom the Jews considered “unclean”—were added to the church (see Acts 8:5-25), as were the Gentiles (see Acts 10; 13–28).

In Acts 1:8 the Lord instructed His disciples, “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” The rest of the book of Acts is a historical account of how Paul, Peter, and others empowered by the Holy Spirit spread Christianity among both Jews and Gentiles around the northern Mediterranean, including Samaria (Acts 8:5-25), Phoenicia, Cyprus, Antioch (9:32–12:25), Phrygia and Galatia (13:1–15:35), Macedonia (15:36–21:16), and Rome (21:17–22:29). Despite persecution by Roman authorities, Jewish authorities, and others (2:13; 4:1-22; 5:17-42; 6:9–8:4), Christianity spread like wildfire.

The apostle Paul went on three missionary tours (Acts 13:1–14:28; 15:36–18:22; 18:23–21:17), spreading God’s Word in strategic cities like Antioch, Perga, Iconium, Lystra, Derbe, Troas, Philippi, Thessalonica, Berea, Athens, Corinth, Ephesus, Galatia, and Miletus. One of Paul’s strategies was to visit major Roman capitals that were easily reached by existing trade routes, a strategy that resulted in the gospel spreading out to other areas through these routes. Local churches popped up one after another.

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century. Christianity has continued to grow and expand from the first century to the present, and it is now variously represented in some 300 denominations in the United States alone. And this number is constantly in flux as new denominations form and other denominations disappear from the religious landscape.

With so many denominations sprinkled across the land, keeping track of their similarities and differences has become increasingly difficult. That is one reason I wrote this book. You will find this book a handy guide that provides a brief history and doctrinal summary of the mainstream denominations in the United States.

the Necessity of Church Fellowship

• “There is nothing more unchristian than a solitary Christian” (John Wesley).

• “The New Testament does not envisage solitary religion; some kind of regular assembly for worship and instruction is everywhere taken for granted in the Epistles. So we must be regular practicing members of the church” (C.S. Lewis).

• “Churchgoers are like coals in a fire. When they cling together, they keep the flame aglow; when they separate, they die out” (Billy Graham).

The English word denomination comes from the Latin word denominare, which means “to name.”1 In this book, you will find that the names of denominations are diverse, reflecting a wide range of distinctive beliefs and practices.

A denomination is “an association or fellowship of congregations within a religion that have the same beliefs or creed, engage in similar practices, and cooperate with each other to develop and maintain shared enterprises.”2 Seen in this light, Presbyterians are Presbyterians precisely because they share the same beliefs, engage in similar practices, and cooperate with each other to develop and maintain shared enterprises. Likewise, Roman Catholics are Roman Catholics for the same reasons.

Though the church experienced some sectarianism even in early New Testament times (see 1 Corinthians 3:3-7), formal denominations are actually a relatively recent development. One reason for this is that in many countries of the world, governmental authorities believed that civic harmony hinged on religious conformity. The recipe for a healthy society, they believed, included “one king, one faith, and one law.”3 This is why so many countries have had state churches. They resisted the idea of allowing people to have freedom of religious belief, for they thought such a policy would be disruptive to society. When denominational groups did emerge in some of these countries, persecution soon followed. Only with the emergence of the United States did all this change in a significant way.

The United States promises every American the free exercise of religion. This is one of the things that makes America so great. The First Amendment, ratified in 1791, affirms that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”4 In keeping with this, James Madison, who became the fourth president of the United States (1809–1817), wrote, “The religion…of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man…We maintain, therefore, that in matters of religion no man’s right is [to be] abridged by the institution of civil society.”5

This policy is one reason so many people immigrated to the colonies in the early years of our country. As these people arrived, they brought with them their churches and denominations.

Among the English colonists there were Congregationalists in New England, Quakers in Pennsylvania, Anglicans in New York, Presbyterians in Virginia, and Roman Catholics in Maryland. In addition, there were Dutch, Swiss, and German Reformed [and] Swiss and German Lutherans.6

Transplanting their former churches onto American soil served to help these immigrants adjust to their new surroundings. They were able to stay grounded in a familiar spiritual environment even while getting used to their new physical environment. Eventually these various churches took on an American flavor and adapted to fit in with American society.

With the passing of time, new denominations continued to emerge on American soil as a result of splits and mergers. Why do denominations split? The answer is simple. Wherever human beings congregate, they will have differences of opinion about what to believe and how faith should be practiced. This book will illustrate how, in many cases, churches split off from a parent denomination because of differences in belief and/or practices, thereby giving rise to entirely new denominations.

• According to the New Testament, church attendance is not merely optional—it is vital.

• Hebrews 10:25 specifically instructs, “Let us not give up meeting together.”

• Scripture describes the Christian life as being lived in the context of the family of God and not in isolation (Acts 2; Ephesians 3:14-15).

• By attending church, believers become equipped for the work of ministry (Ephesians 4:12-16).

• The Bible knows nothing of “lone ranger” Christians (see Ephesians 2:19; 1 Thessalonians 5:10-11; and 1 Peter 3:8).

What Are Protestants?

The three major divisions of Christianity are the Roman Catholic Church, the Protestant Church, and the Orthodox Church. I provide a full history of how the Roman Catholic Church (chapter 4) and the Orthodox Church (chapter 14) emerged. However, the great majority of denominations in this book—including those affiliated with the Methodists, the Baptists, the Presbyterians, and the Lutherans—are Protestant. Therefore, an introductory history of Protestantism may be helpful.

Protestantism refers to a broad system of the Christian faith and practices that emerged in the sixteenth century. It began as a movement seeking to bring reform to the Western (Roman Catholic) Church.

The term Protestant was first coined in 1529 at the Diet of Speyer, an imperial assembly. Just three years earlier, another diet (or formal assembly) had granted tolerance to the Lutherans, allowing them to determine their own religious position. At the Diet of Speyer, the Roman Catholic majority of delegates rescinded this tolerance.

Consequently, six Lutheran princes and the leaders of fourteen German cities signed a protest against this action, and it was then that Lutherans became known as Protestants. Gradually, however, the term Protestant came to embrace all churches that were not affiliated with (and that had separated from) Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. This small beginning eventually mushroomed to embrace more than 400 million people (as of AD 2000). About one-fifth of all Christians are Protestant.

One religious researcher suggests, “If the Christian church you’re sitting in isn’t Orthodox or Roman Catholic, then you are in a Protestant church of one variety or another. The thing to remember about Protestants is that they protest.”7 One cannot deny the element of protest in the history of Protestantism. Many scholars are quick to note, however, that the term protest etymologically carries the idea “to testify” or “to affirm.” Robert McAfee, in his book The Spirit of Protestantism, gives us this interesting insight:

The verb “to protest” comes from the Latin protestari, and means not only “to testify” but, more importantly, “to testify on behalf of something.” Webster’s Dictionary gives as a synonym, “to affirm.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines it, “to declare formally in public, testify, to make a solemn declaration.” The notion of a “protest against error” is only a subsidiary meaning. Thus, the actual word itself is charged with positive rather than negative connotations. “To protest,” then, in the true meaning of the word, is to make certain affirmations, to give testimony on behalf of certain things.8

The point, then, is that Protestantism is not simply a reactionary, negative movement. To be sure, the early Reformers did take a stand against the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. But Protestants predominantly testify to what they consider to be the truth!

Distinctive Emphases of Protestantism

Protestants have strong convictions on quite a number of doctrines, but three are particularly important. These three serve to distinguish Protestantism from Roman Catholicism.

1. The exclusivity of the Bible. Protestants view the Bible as the only infallible rule of the Christian life and faith. It is considered the sole source for spiritual teachings. This is in obvious contrast to Roman Catholicism, which places heavy emphasis on the authority of tradition and the ex cathedra pronouncements of the pope.

2. Salvation by grace alone through faith alone. Protestants have always emphasized that the benefits of salvation are by grace alone through faith alone (Romans 4; Galatians 3:6-14; Ephesians 2:8-9). By contrast, Roman Catholics have historically placed a heavy emphasis on meritorious works in contributing to the process of salvation. This is not to say that Protestants view good works as unimportant. They simply believe good works are by-products of salvation (Matthew 7:15-23; 1 Timothy 5:10,25).

3. The priesthood of all believers. In Roman Catholicism, the priest is the intermediary between the believer and God. For example, a person must confess sins to a priest, who then absolves that person of sin. By contrast, Protestants believe each Christian is a priest before God and thus has direct access to Him without need for an intermediary (see 1 Peter 2:4-10).

Divisions Within Protestantism

The independent spirit intrinsic to Protestantism has been both a strength and a weakness. It has been a strength in that it has had a revitalizing effect on church members who are free to directly interact with God and serve Him freely in the church. It has been a weakness in that such independence has led to numerous denominational splits throughout history.

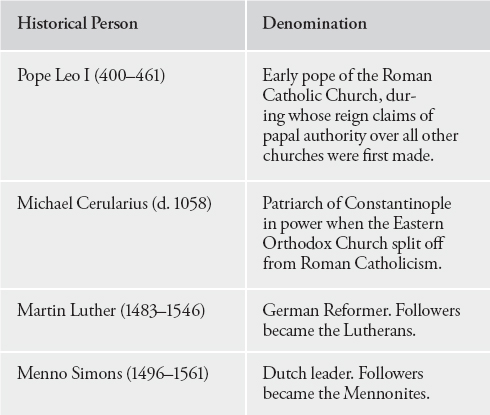

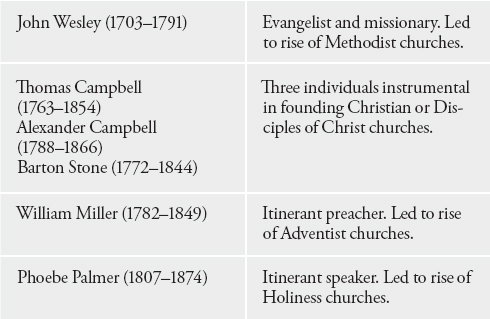

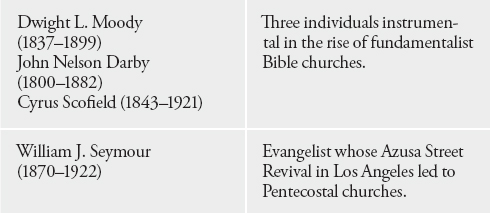

Today, Protestantism includes many denominations—each having some distinctive beliefs and histories. Lutheran churches, for example, emerged out of the reforming work of Martin Luther in the early sixteenth century in Germany. Churches in both the Presbyterian and Reformed traditions emerged largely from the Calvinistic side of the Reformation. The Methodist church grew out of the holiness teachings of John Wesley. The work of several influential Christian leaders gave rise to new denominations.

This book is divided into 17 alphabetized groupings of denominations—Adventist churches; Baptist churches; Brethren churches; Catholic churches; Christian churches; Congregational churches; Episcopal and Anglican churches; Friends (Quaker) churches; fundamentalist, Bible, and conservative Evangelical churches; Holiness churches; Lutheran churches; Mennonite churches; Methodist churches; Orthodox churches; Pentecostal churches; Presbyterian churches; and Reformed churches. In each case, I provide a brief history of the emergence of the group as a whole before dealing with specific denominations in that group. For example, I provide a brief Baptist history before providing information on relevant Baptist denominations.

This book is not intended as an apologetic critique of each denomination. Rather, it is intended to provide a brief history and doctrinal summary of the major denominations in North America. I do not personally endorse the teachings of some of the denominations in this book.

Unlike some other denomination handbooks, this book does not provide information about denominations from Judaism, world religions like Islam, or cultic groups. For example, you will not find listed in this volume information on the Mormons or the Jehovah’s Witnesses. These groups may claim to be Christian but in fact are not Christian because they deny one or more of the essential doctrines of Christianity as taught in the 66 books of the Bible.9 (See appendix B, “Cults Are Not Denominations.”)

For each denomination I provide statistics on church membership and the number of congregations in the denomination. Please note, however, that these statistics should not be taken as “gospel truth.” Some churches, in their membership rolls, count all baptized persons, including infants. Others exclude infants and include only adults who have made a formal profession of faith in Christ. Some churches include only members in good standing. Others include people who officially joined the church at some point but rarely ever attend services. Some churches are not careful about excluding the deceased or those who have left their congregations. In a number of cases, one person may be on the membership rolls of more than one church.10 Such factors make obtaining exact figures extremely difficult, if not impossible. Nevertheless, the figures presented in this book are good guesstimates.

Though I seek to provide helpful doctrinal summaries of the various denominations I cover in this book, some of them publish less information than others regarding their beliefs. For this reason, some denominations in this book have briefer doctrinal summaries than others.

Moreover, I have chosen to allow each denomination to speak for itself as to its doctrinal position. I based my doctrinal summaries on the doctrinal statements of the various denominations. There is both an upside and a downside to this. The upside is fair doctrinal representation. The downside is that in many cases, the doctrinal statements I examined were somewhat vague. I soon came to recognize that one reason for vague doctrinal statements is to allow a bit of wiggle room for churches within a denomination. In other words, vagueness in doctrinal statements allows for at least some diversity of beliefs among associated churches.

Still, each broad family of denominations—Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, and the like—has notable distinctions. In each chapter, I have included a brief section noting some of the primary distinctions.

You will also notice many charts of Fast Facts scattered throughout the book. These are intended to provide general information in a concise format. An index of these charts is provided at the back of this book.

For most denominations, an Internet website address is provided so you can easily obtain more information. The bibliography includes additional websites and other resources. The website addresses are accurate as of the time of publication. A regularly updated list of website addresses for denominations is available at www.ronrhodes.org.