14 Obtaining the History of Present Illness

Essential Questions

- What has been happening over the past week or two that has brought you into the clinic?

- Have there been any events that you think have caused your problem or made it worse?

- Have you sought any treatment for this problem?

Recommended time: 10 minutes

What is the History of Present Illness?

The HPI is probably the most important part of the psychiatric interview, and yet, there is disagreement on exactly what it should entail. Even experienced clinicians differ in how they approach the HPI. Some think of it as the “history of present crisis” and focus on the preceding few weeks. Such clinicians begin their interviews with questions such as, “What has been going on recently that brings you into the clinic today?” Others begin by eliciting the entire history of the patient’s primary syndrome: “Tell me about your depression. How old were you when you first felt depressed?” These clinicians work forward to the present episode.

Each of these approaches may be useful, depending on the clinical situation. If a patient has a relatively uncomplicated and brief psychiatric history, it might make sense to explore that first and then move to the HPI. If the psychiatric history is long, with many hospitalizations and caregivers, starting at the beginning may bring you too far from the present problem.

The most common pitfall for beginners is spending too much time on the HPI. It’s easy to do, because this is the time for your patient to share the most difficult and painful part of his story, and cutting your patient off as time begins to pass may seem unempathic. Thus, it is vital that you keep in mind the advice offered in Section I about asking questions and changing topics sensitively. Use these techniques to gently but persistently bring the patient back to the HPI.

In the following sections, I describe techniques for the two major approaches to the HPI; you should decide which to use for a given patient.

The History of Present Crisis Approach

The American Heritage Dictionary defines crisis as “A crucial point or situation in the course of anything; a turning point.” As you begin the interview, ask yourself, “Why now? Why is this a crucial point in this person’s life? What has been happening recently to bring her into my office?” Often, psychiatric crises occur over a 1- to 4-week period, so focus your initial questions on this period.

History of the Syndrome Approach

Alternatively, you can begin your questioning by ascertaining when the patient first remembers signs of the illness.

Ensuing questions track the course of the illness through months or years, arriving eventually at the present.

One nice thing about this approach to the HPI is that most case write-ups are organized in this format—they often begin, “The patient was without any psychiatric problems until age 18, when she became depressed….”

MAKING THE INTERVIEW ELEGANT, OR THE “BARBARA WALTERS APPROACH”

MAKING THE INTERVIEW ELEGANT, OR THE “BARBARA WALTERS APPROACH”

At its best, a well-conducted interview resembles a dance in which the give and take between clinician and patient flow effortlessly throughout the hour, giving the patient the sense that he just participated in a fascinating conversation about his life rather than a “psychiatric” interview. One way to set the stage for this type of experience is to begin the interview by showing genuine interest and curiosity about the patient’s job, hobbies, or life situation and to allow the patient to steer the discussion toward clinical topics. Imagine that you are Barbara Walters interviewing a celebrity, bringing that same intense curiosity to your patient:

Interviewer: I see from your intake sheet that you work for the IRS. What do you do with them?

Patient: I’m in their call center, but it’s only seasonal.

Interviewer: So when I call the IRS to ask for a form, you might answer?

Patient: Yes, but I do a lot more. I can answer questions about a customer’s return.

Interviewer: Wait, you’re kidding. If I were to call you and ask how much I owed, you’d be able to pull that information up while I was on the phone?

Patient: Oh yes, we have the whole database available, at least when the computers aren’t down! It’s really a great job, my first good job, but during the summer I’m usually laid off, and I don’t know why (patient appears dejected).

Interviewer: That’s too bad, why do they lay you off? (The patient begins to describe difficulties leading up to her current depression.)

Elicit a Chronologic Narrative, Emphasizing Precipitants

Many patients automatically jump into a chronologic narrative of their problems when prompted by one of the preceding questions. If this happens, it is a time to fall silent for a while and listen. Remember, this is your “scouting period” (see Chapter 3), during which you are observing, listening, and hypothesizing. However, if your patient begins to jump around into other issues or time frames, you may want to refocus him.

Patient: I felt so angry when my wife yelled at me. But she’s always been that way. Back when I was in law school, she nagged at me constantly. I’d have to spend late nights at the law library, and she refused to understand.

Interviewer: I’d like to hear more about that period later, but right now let’s focus on what’s been happening over the last 2 weeks or so. You said you got angry at her. What happened then?

Ask the patient specifically about potential precipitants for her suffering:

Occasionally, the patient will deny any precipitants. This is particularly true of patients who view their psychiatric illness from a medical model. Such a patient might answer the question above with

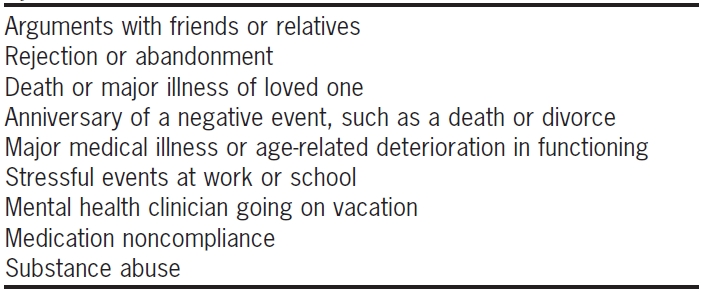

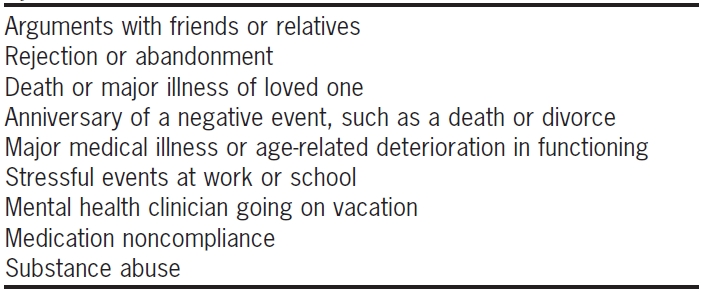

Certainly, some psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder, can have lives of their own, but it’s unusual for patients to decompensate without some precipitant. Often, patients haven’t associated particular events with their pain and simply need their memories jogged. Make it a practice to dig by asking about specific events that commonly destabilize patients (Table 14.1). You won’t necessarily ask about every item on this list, of course. You may already have some clues from an earlier part of the interview that one of these events is particularly likely. As you ask these questions, remember that correlation does not equal causality. A stressful psychosocial event may have occurred around the time of a psychiatric problem and yet be unrelated to it.

TABLE 14.1. Common Precipitants of Psychiatric Syndromes

Launch into the Diagnostic Questions Right Away

One of the secrets of efficient and rapid diagnostic interviewing is a gentle tenacity; when the patient mentions a depressed mood, immediately assess for the presence of the diagnostic criteria for depression.

Patient: I think the worst problem over the past couple of weeks is that I’ve felt so down about myself.

Interviewer: Has that down feeling been affecting your sleep?

Patient: I haven’t slept more than 2 or 3 hours a night, and the next day, I can barely drag myself to work. I should probably quit anyway; it’s a boring job.

Interviewer: Have you had problems focusing on your work because of your depression?

Here, the interviewer stays on the depression topic by cueing off what the patient has said about work (see the discussion of the smooth transition in Chapter 6). If the interviewer had not actively structured the interview this way, the patient might have discussed details of his work environment that would be less relevant to the diagnosis of major depression. Later, when ascertaining the social history, the interviewer can refer to what the patient said about work:

Interviewer: Earlier, you mentioned that your work is boring. How did you get into that line of work? (Note the use of the referred transition.)

Current and Premorbid Level of Functioning

The now outdated DSM-IV-TR diagnostic scheme included an “Axis V” in which you noted the patient’s “GAF,” or global assessment of functioning, on a scale of 0 to 100. Although I never found it useful to assign a specific number to functioning (only insurance companies were obsessed with that number), I do think that Axis V was an important reminder to the interviewer to ask about both current and baseline functioning.

To assess overall functioning, ask about the three basic aspects of life: love, work, and fun. Love includes all important relationships: family, spouse, and close friends. In addition to paid employment, work includes school, volunteer activities, and the structured day activities in which many chronically mentally ill patients participate. Fun refers to hobbies and recreational pursuits.

The phrasing of this question automatically targets the patient’s premorbid functioning. Some patients have a hard time distinguishing a psychiatric illness from the rest of their lives. If so, you will have to follow up with another question to assess their baseline functioning.

For patients who have more chronic illnesses with multiple exacerbations and remissions, ask the same types of questions about periods between exacerbations:

Asking about current versus baseline functioning is important diagnostically. The classic example is the difference between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. In schizophrenia, the patient’s level of functioning gradually decreases over months or years, whereas in bipolar disorder, the patient may have been functioning dramatically better within the past few weeks. Determining baseline functioning is also important in setting treatment goals. You might aim to help the patient achieve his best level of functioning over the past year, for example.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE

A resident was working in a busy psychiatric crisis clinic and interviewed a patient who was brought by ambulance for psychotic and disorganized behavior. The patient was a 32-year-old woman and carried the diagnosis of “schizoaffective disorder” in her previous emergency department records. The phrase “history of multiple psychiatric hospitalizations” in the old chart caused the resident to assume that the patient was a chronically poorly functioning woman who could rarely stay out of a hospital. In assessing her psychosocial functioning, the resident was surprised to learn that the patient had been working as a secretary for a research department of a local hospital until 1 year ago, when she had the first of a series of recent hospitalizations. This information caused the resident to pay closer attention to the patient’s history and to entertain the possibility of a different diagnosis, such as borderline personality disorder or PTSD, both of which would be more consistent with her good premorbid functioning.

![]() MAKING THE INTERVIEW ELEGANT, OR THE “BARBARA WALTERS APPROACH”

MAKING THE INTERVIEW ELEGANT, OR THE “BARBARA WALTERS APPROACH”