17 Family Psychiatric History

Screening Questions

- Has any blood relative ever had nervousness, a nervous breakdown, depression, mania, psychosis or schizophrenia, alcohol or drug abuse, suicide attempts, or hospitalization for nervousness?

- Has any blood relative ever had a medical or neurologic illness, such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer, seizures, or senility?

Recommended time: 2 minutes for bare bones; 5 minutes for genogram.

The family history may be approached in one of two ways. One is the bare-bones approach, which aims to ascertain the patient’s inherited risk of developing a psychiatric or medical disorder. The second approach is more extensive and is a way of beginning the social history part of the interview. I describe both approaches here and let you decide which works best for you.

Bare-Bones Approach

Ask the following long, high-yield question, which is adapted from a question suggested by Morrison and Munoz (2009):

Because the question is so long, you have to ask it very slowly, pausing after each disorder so that the patient has time to think about it. You should also define blood relative.

TIP

TIP

If the patient answers with a definitive “no,” you can move on. If there was a “yes,” you should try to determine exactly what the diagnosis was. Unless your patient is in the mental health field and is familiar with its jargon, this may not be easy. It’s helpful to ask about specific treatments the relative may have received, such as lithium, carbamazepine (Tegretol), divalproex sodium (Depakote) (clues to bipolar disorder), antipsychotics [older examples are haloperidol (Haldol) and chlorpromazine (Thorazine); newer ones are risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), ziprasidone (Geodon), aripiprazole (Abilify), lurasidone (Latuda), and several others], electroconvulsive therapy (clue to depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, depending on when the treatment was administered), antidepressants, and antianxiety agents. Remember that medications were used differently 20 years ago. For example, in its heyday, diazepam (Valium) was given to many patients for depression, whereas now, a history of benzodiazepine treatment is a clue for the presence of an anxiety disorder.

To determine a family history of transmissible medical and neurologic problems, ask

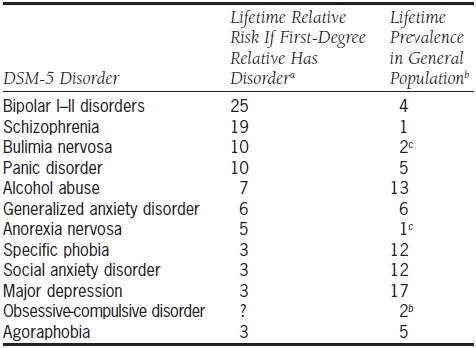

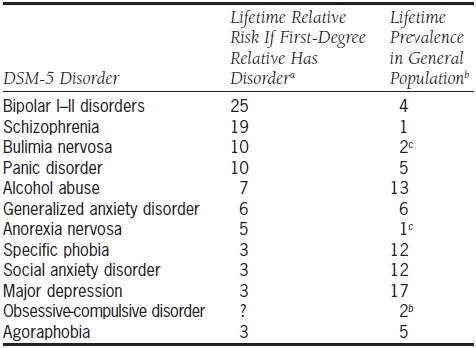

How does it help diagnostically to know that a patient has a first-degree relative with a psychiatric disorder? Table 17.1 lists those psychiatric disorders for which there is significant evidence of familial transmission. The relative risk compares the risk for people with such a family history against the risk of people in the general population, who are assigned a relative risk of 1.0. For example, the relative risk of developing bipolar disorder is 25; this means that if your patient’s father is bipolar, she is 25 times more likely to develop bipolar disorder than the average person. The baseline lifetime prevalence of each disorder is also listed in the table.

TABLE 17.1. Psychiatric Disorders with Significant Evidence of Familial Transmission

Typically, family information is used in conjunction with other clinical information. For example, family history is crucial in deciding whether a patient with new-onset psychosis has schizophrenia or is in the manic phase of bipolar disorder.

The Genogram: Family History as Social History

Doing a genogram takes a while, which probably explains its lack of popularity in most clinical settings. But it doesn’t take that long, and the time investment usually pays off in terms of richness of information. The genogram serves the additional function of introducing you to the patient’s developmental history.

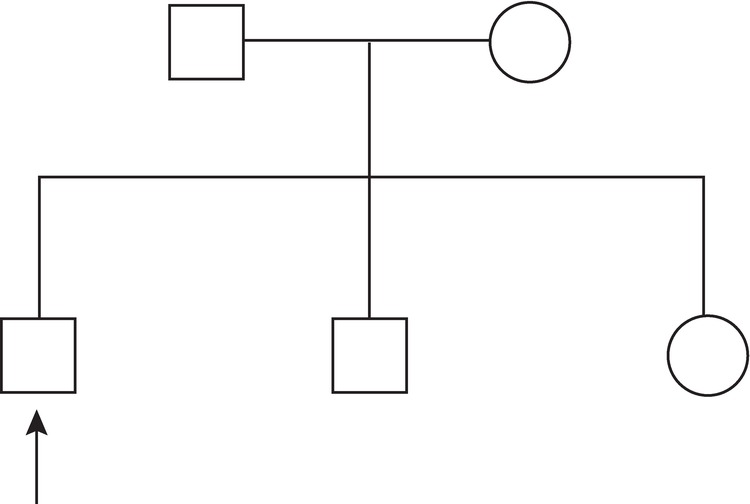

The technique is simple. Begin by telling your patient that you’d like to draw a family diagram to better understand her family. Draw small squares for males and circles for females. Obtain the following information about each relative:

- Age

- If dead, year, age, and cause of death (put slash mark through square or circle if dead)

- Presence of psychiatric problem, substance abuse, or major medical problem

- Status of the patient’s relationship with relative (e.g., close, estranged, a perpetrator or victim of sexual or physical abuse)

Begin by diagramming the first-degree relatives, with the oldest sibling on the right (Fig. 17.1).

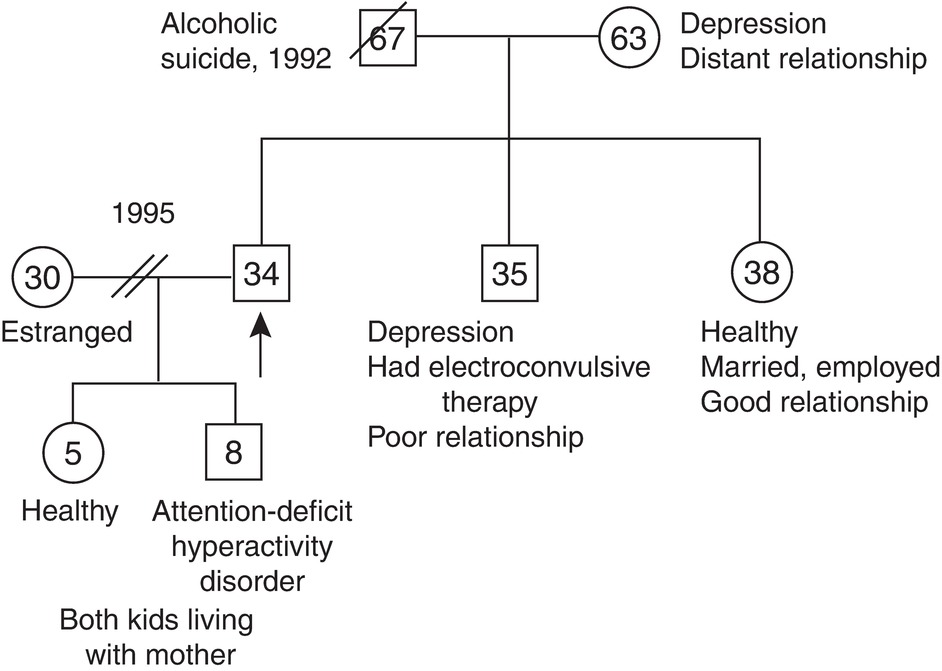

Once you have the skeleton of the chart, ask about each family member and embellish the chart with the information obtained. Although you will likely develop your own preferences, it is standard to write the age within the circle or square, to use slashes to represent the deceased, and to use double slashes to represent a divorce. In the example in Figure 17.2, the patient is a divorced 34-year-old man with two children who has a family psychiatric history significant for alcoholism and depression.

Once you have completed a genogram, you have accomplished three tasks: you have obtained (a) the family psychiatric history, (b) the family medical history, and (c) the bare bones of the social and developmental history. Also, the physical layout of the genogram makes it a quick way to remind yourself of the patient’s social situation, a particularly nice feature if you rarely see the patient.

![]() TIP

TIP