19 How to Memorize the DSM-5 Criteria

Essential Concepts

DSM-5 Mnemonic:

- Depressed Patients Sound Anxious, So Claim Psychiatrists

- Depression and other mood disorders

- Psychotic disorders

- Substance abuse disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Somatic disorders

- Cognitive disorders

- Personality disorders

Everything should be as simple as it is, but not simpler.

Albert Einstein

In this chapter, I describe an approach to memorizing the criteria for the major DSM-5 disorders. These mnemonics are a way of sorting information into manageable chunks. Those who have researched the way expert clinicians think have found that this “chunking” process is quite common (Kaplan 2011). The father of chunking, Miller (1957), showed that humans can only process about 7 (±2) bits of information at a time, which is, presumably, why phone numbers have seven digits. You have to be able to process more than seven items to master the DSM-5, but mnemonics help by grouping items into information-packed chunks.

Memorize the Seven Major Diagnostic Categories

Begin by mastering the following mnemonic for the seven major adult diagnostic categories in the DSM-5:

Depressed Patients Sound Anxious, So Claim Psychiatrists.

Depression and other mood disorders (major depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia)

Psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder)

Substance abuse disorders (alcohol and drug use, psychiatric syndromes induced by drug and alcohol use)

Anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD])

Somatic disorders (somatic symptom disorder, eating disorders)

Cognitive disorders (dementia, mental retardation, ADHD)

Personality disorders

Notice that these categories deviate somewhat from DSM-5 dogma. For example, I call ADHD a “cognitive disorder,” whereas the DSM-5 classifies it as a “neurodevelopmental disorder.” Also, I classify eating disorders under somatic disorders, whereas the DSM-5 puts them in a separate chapter. My purpose here is not to create a new classification of psychiatric disorders but simply to rearrange them into seven categories for ease of memorization.

Focus on Positive Criteria

Now that you’ve memorized the major disorders, you need to memorize the diagnostic criteria. Begin by disregarding the voluminous exclusions and modifiers listed by the DSM-5 and instead focus on the actual behaviors and affects needed to make the diagnosis.

For example, under schizophrenia in the DSM-5 are six categories of criteria, labeled A through F. B is the usual proviso that the disorder must cause significant dysfunction, which is true for all the disorders, so you don’t need to memorize it. D tells you to rule out schizoaffective and mood disorder before you diagnose schizophrenia—another obvious piece of information; don’t use up valuable neurons memorizing it. E reminds you to rule out substance abuse or a medical condition, which you should do before making any diagnosis, and F deals with the arcane issue of diagnosing schizophrenia in someone who’s autistic. So, only two essential criteria are left: A (symptoms) and C (duration).

This section lists mnemonics for most of the major disorders, but it does not cover how to ascertain the diagnoses, which involves the skillful use of screening questions and specific follow-up questions. These are covered in detail in Chapters 23 to 31, where the full DSM-5 criteria are spelled out.

KEY POINT

KEY POINT

How should you use these mnemonics? They are primarily an aid to ensure that you remember to ask about major diagnostic criteria. Do not ask the questions in the same order as the mnemonics; doing so would lead to a very stilted interview. Try to ask diagnostic questions when they seem to fit naturally into the context of the interview, using some of the techniques for making transitions already discussed in Chapters 4 and 6.

Unless stated otherwise, these mnemonics are the products of my own disordered brain.

Mood Disorders

Major Depression: SIGECAPS

Four out of these eight, with depressed mood or anhedonia, for 2 weeks signify major depression:

Sleep disorder (either increased or decreased sleep)

Interest deficit (anhedonia)

Guilt (worthlessness, hopelessness, regret)

Energy deficit

Concentration deficit

Appetite disorder (either decreased or increased appetite)

Psychomotor retardation or agitation

Suicidality

This mnemonic, devised by Dr. Carey Gross of the MGH Department of Psychiatry, refers to what might be written on a prescription sheet for a depressed, anergic patient—SIG: Energy CAPSules. Each letter refers to one of the major diagnostic criteria for a major depressive disorder. To meet the criteria for an episode of major depression, your patient must have had four of the preceding symptoms and depressed mood or anhedonia for at least 2 weeks.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia): ACHEWS

Two out of these six, with depressed mood, for 2 years signify persistent depressive disorder:

Appetite disorder (either decreased or increased)

Concentration deficit

Hopelessness

Energy deficit

Worthlessness

Sleep disorder (either increased or decreased)

The dysthymic patient is “allergic” to happiness; hence, the mnemonic refers to a dysthymic patient’s (misspelled) sneezes (achoos) on exposure to happiness. To meet the criteria, the patient must have had 2 years of depressed mood with two of the six symptoms in the mnemonic.

Manic Episode: DIGFAST

Elevated mood with three of these seven, or irritable mood with four of these seven, for 1 week signify a manic episode:

Distractibility

Indiscretion (DSM-5’s “excessive involvement in pleasurable activities…”)

Grandiosity

Flight of ideas

Activity increase

Sleep deficit (decreased need for sleep)

Talkativeness (pressured speech)

I don’t know who came up with this jewel, but I use it all the time. DIGFAST apparently refers to the speed with which a manic patient would dig a hole if put to the task. A complication in the diagnosis is that if the mood is primarily irritable, four of seven criteria must be met to qualify.

Psychotic Disorders

Schizophrenia: Delusions Herald Schizophrenic’s Bad News

Requires two symptoms for 1 month, plus 5 months of prodromal or residual symptoms. At least one symptom must be one of the three highlighted core symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, speech disorganization).

Mnemonic: Delusions Herald Schizophrenic’s Bad News

Delusions

Hallucinations

Speech/thought disorganization

Behavior disorganization

Negative symptoms

Substance Use Disorder

The same mnemonic, Tempted With Cognac, is used for criteria for any drug or alcohol dependence (two of the following eleven criteria are required):

- Tolerance, that is, a need for increasing amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication

- Withdrawal syndrome

- Loss of Control of alcohol use (nine criteria follow):

- More alcohol ingested than the patient intended

- Unsuccessful attempts to cut down

- Much time spent in activities related to obtaining or recovering from the effects of alcohol

- Craving alcohol

- Alcohol use continued despite the patient’s knowledge of significant physical or psychological problems caused by its use

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities given up or reduced because of alcohol use

- Failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

- Persistent social and interpersonal problems caused by alcohol

- Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous

For alcohol use, the CAGE questionnaire is often used:

Two or more affirmative answers indicate a high probability of alcohol use disorder (Ewing 1984).

Anxiety Disorders

Panic Attack (4 of 13)

With so many separate criteria to remember (13 total), trying to recall them with an acronym or phrase is not practical. My trick instead is to break the symptoms down into three clusters: (a) the heart, (b) breathlessness, and (c) fear. To remember them, I visualize a panicking patient clutching his chest (heart cluster), hyperventilating (breathlessness cluster), and shaking with fear (fear cluster). Finally, I imagine him screaming out, “Three-five-five! Three-five-five!”—presumably as a way of distracting himself from the panic attack. The numbers refer to the number of criteria in each cluster: The heart cluster has three criteria, and the other two clusters have five each.

I admit that this all sounds hokey, but believe me, you’ll never forget the criteria if you do it!

Heart Cluster: Three

I think of symptoms that often accompany a heart attack:

- Palpitations

- Chest pain

- Nausea

Breathlessness Cluster: Five

I think of symptoms associated with hyperventilation, which include dizziness, light-headedness, tingling of the extremities or lips (paresthesias), and chills or hot flashes:

- Shortness of breath

- Choking sensation

- Dizziness

- Paresthesias

- Chills or hot flashes

Fear Cluster: Five

I associate shaking and sweating with fear. To remember derealization, think of it as a way of psychologically escaping panic.

- Fear of dying

- Fear of going crazy

- Shaking

- Sweating

- Derealization or depersonalization

Aside from remembering the cluster names, remember the pattern 3-5-5 to keep from missing any of the 13 criteria. Your patient must have experienced four symptoms to meet the criteria for a full-scale panic attack.

Agoraphobia

I have no mnemonic for agoraphobia, because there are really only two criteria: a fear of being in places where escape might be difficult and efforts to avoid such places. See Chapter 25 for details.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The requirement for the diagnosis of OCD is the presence of obsessions, compulsions, or both to a degree that causes significant dysfunction. The definitions of obsessions and compulsions are easily learned and remembered (see Chapter 25), so a mnemonic is not necessary. Instead, I have chosen some of the most common symptoms seen in clinical practice; none of them is specifically required to be present by DSM-5.

Washing and Straightening Make Clean Houses:

Washing

Straightening (ordering rituals)

Mental rituals (e.g., magical words, numbers)

Checking

Hoarding (in DSM-5, there is now a separate “hoarding disorder”)

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The PTSD patient Remembers Atrocious Nuclear Attacks.

Reexperiencing the trauma via intrusive memories, flashbacks, or nightmares (one of which is required for diagnosis)

Avoidance of stimuli associated with trauma

Negative alterations in cognitions and mood (e.g., amnesia for the trauma, negative beliefs about oneself or the world, irrationally blaming oneself for the trauma, negative emotional state, restricted interests and activities, detachment, and inability to have positive emotions; two required for diagnosis)

Arousal increase, such as insomnia, irritability, hypervigilance, startle response, reckless behavior, and poor concentration (two required for diagnosis)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Three of Six)

The first part of the diagnosis of GAD is easy: The patient has worried excessively about something for 6 months. The hard part is remembering the six anxiety symptoms, three of which must be present. The following mnemonic is based on the idea that Macbeth had GAD before and after killing King Duncan:

Macbeth Frets Constantly Regarding Illicit Sins:

Muscle tension

Fatigue

Concentration problems

Restlessness, feeling on edge

Irritability

Sleep problems

If this elaborate acronym isn’t to your liking, an alternative is imagining what you would experience if you were constantly worrying about something or other. You’d have insomnia, leading to daytime fatigue. Fatigue in turn would cause irritability and problems concentrating, and constant worry would cause muscle tension and restlessness.

Eating Disorders

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimics Over Consume Pastries (all four of these):

Binging

Out-of-control feeling while eating

Concern with body shape

Purging

Anorexia Nervosa

Weight Fear Bothers Anorexics (all three of these):

Weight significantly low

Fear of fat

Body image distortion

Cognitive Disorders

Dementia

At least one of the following six symptoms:

Memory LAPSE

1. Memory

2. Language

3. Attention (complex)

4. Perceptual-motor

5. Social cognition

6. Executive function

See Chapters 21 and 28 for further information on assessing these symptoms.

Delirium

Medical FRAT (all five of these):

Medical cause of cognitive impairment

Fluctuating course

Recent onset

Attention impairment

Thinking (cognitive) disturbance

Because delirium is caused by a medical illness, being part of the “medical fraternity” helps to diagnose it. To merit the diagnosis, all five criteria must be present. See Chapter 28 for details.

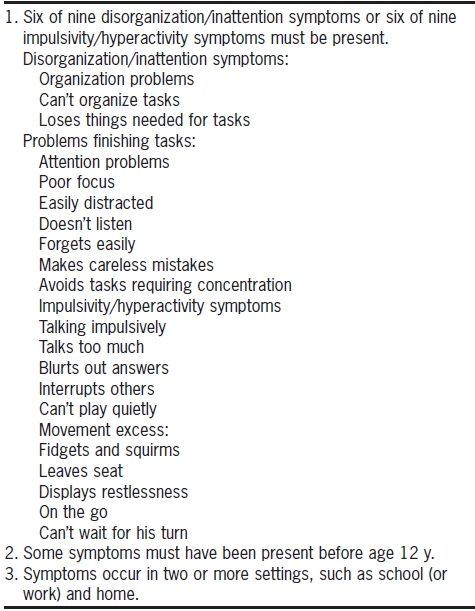

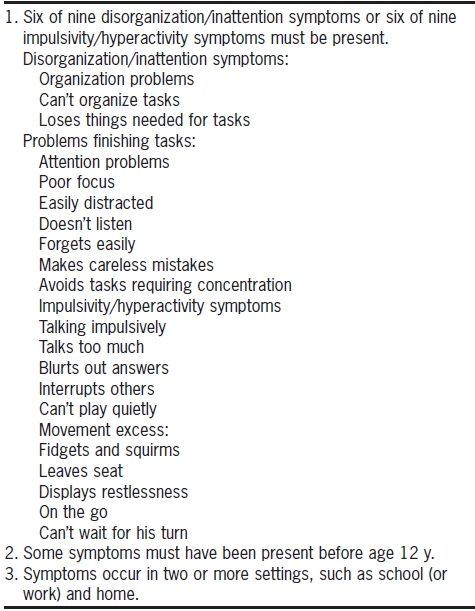

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

There are 18 separate, though often redundant, criteria for ADHD, making memorization impossible for anyone without a photographic memory (Table 19.1). As with panic disorder, I suggest breaking the symptoms into four broad categories, which can be remembered by the mnemonic MOAT (you’ll need a MOAT around the classroom for the hyperactive child):

TABLE 19.1. DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD

Data from American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Movement excess (hyperactivity)

Organization problems (difficulty finishing tasks)

Attention problems

Talking impulsively

Personality Disorders

Chapter 31 outlines a system for diagnosing personality disorders in general, including mnemonics for all ten of the personality disorders, which are not repeated here.

![]() KEY POINT

KEY POINT