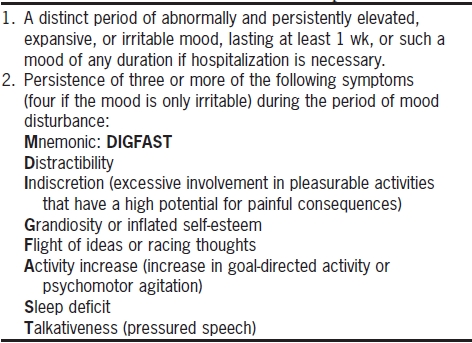

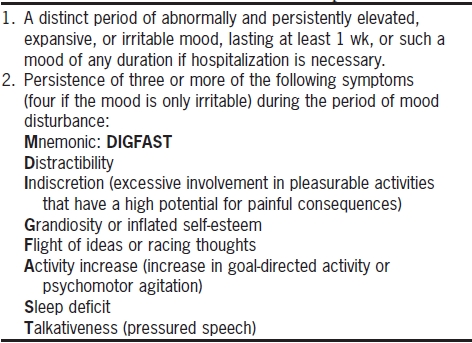

TABLE 24.1. DSM-5 Criteria for Manic Episode

Data from American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Essential Concepts

Screening Questions

Mnemonic: DIGFAST

Recommended time: 1 minute if negative screen; 5 minutes if positive screen.

Bipolar disorder tends to be under diagnosed by beginning clinicians. Most patients who present for psychiatric interviews appear demoralized, depressed, or anxious, and one isn’t intuitively moved to ask about periods of extreme happiness. It’s helpful to realize that bipolar disorder usually presents first as a major depression and that up to 20% of patients with depression go on to develop bipolar disorder (Blacker and Tsuang 1992).

Even when you do remember to ask about mania, there is another roadblock: a high rate of false-positive responses. Many patients report periods of euphoria and high energy that represent normal variations in mood rather than mania. Thus, the most effective screening questions for mania ask about other people’s perceptions as well as the patient’s self-perception.

In general, you should keep referring to a particular period as you ask your questions, because many people experience the separate diagnostic criteria of mania at various points in their lives (e.g., spending foolishly, talking unusually fast, being unusually distractible), but unless a number of these symptoms have co-occurred during a discrete period (at least 1 week or 4 days for hypomania), a manic episode cannot be diagnosed (Table 24.1).

TABLE 24.1. DSM-5 Criteria for Manic Episode

Data from American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Have you ever had a period of a week or so when you felt so happy and energetic that you didn’t need to sleep and your friends told you that you were talking too fast or that you were behaving differently and strangely?

If you get a “yes” here, find out when that period was and how long it lasted, and then continually refer to that period when you ask about the diagnostic criteria for mania. If the patient cannot remember such a period lasting an entire week, you should suspect that mania is not the diagnosis. Determine the circumstances of the elevated mood. Being really happy for a couple of days after college graduation, for example, is not mania.

Has there been a time when you felt just the opposite of depressed, so that for a week or so you felt as if you were on an adrenaline high and could conquer the world?

The preceding question about mania is handy if you have just finished asking about symptoms of depression.

Do you experience wild mood swings in which you feel incredibly good for a week or more and then crash down into a depression?

Interpret responses to this question cautiously, because some patients who respond with an emphatic “yes” are referring to recurrent episodes of depression without mania or hypomania.

Have you had periods when you were snapping at people all the time and getting into arguments with them?

This gets at the diagnosis of irritable, mixed, or dysphoric mania. Obviously, false-positive responses abound here, and following up with questions establishing that this period of irritability represented a manic episode, rather than a depression or simply a transient foul mood, will be no small task.

Has anyone ever said that you were manic or that you had bipolar disorder?

If someone answers “yes” to this, pay close attention. It’s not common for healthy people to have been called manic by someone.

The author of the DIGFAST jewel is unknown, but it’s very useful in remembering the diagnostic criteria for a manic episode. The term apparently refers to the speed with which a manic patient would dig a hole if put to the task.

Mnemonic: DIGFAST

Distractibility

Indiscretion (DSM-5’s “excessive involvement in pleasurable activities”)

Grandiosity

Flight of ideas

Activity increase

Sleep deficit (decreased need for sleep)

Talkativeness (pressured speech)

In addition to expansive mood, the patient must qualify for three of the seven DIGFAST symptoms, or four of seven if the primary mood is irritable.

When you ask about the symptoms of mania, precede your questions with something such as, “During the period last year when you felt high, were you …?” This way, you can ensure that all the symptoms have occurred within the same time frame.

![]() TIP

TIP

Be sure to ask whether these behaviors occurred in the context of alcohol or drug abuse. If so, you’ll have to judge whether the manic behavior is actually secondary to a substance abuse problem or whether the substance abuse is secondary to mania. This is often a difficult question to sort out.

Were you having trouble thinking? Was this because things around you would get you off track?

During the period we’ve been talking about, how did you spend your time?

Were you doing things that were out of character or unusual for you?

These are nice questions to start with, because they are relatively unbiased and unlikely to lead the patient to invalid responses.

This is a good question because it doesn’t imply a judgment of the morality of any particular behavior—it merely asks if a behavior has caused trouble for anyone.

Were you doing things that showed a lack of judgment, such as driving too quickly, running red lights, or spending too much money?

Did you do anything sexual during this period that was unusual for you?

During this period, did you feel especially self-confident, as if you could conquer the world?

Did you have particularly good ideas?

Did you feel that you were right and that everybody else was wrong?

Often, this is a good opportunity to elicit the grandiose delusions that are so common in mania:

Did you feel like you had any special powers?

Did you feel more religious than normal?

Did you have so many ideas that you could barely keep up with them?

Were thoughts racing through your head?

Were other people having a hard time understanding your ideas?

When assessing flight of ideas, be aware that “racing thoughts” per se are not specific to bipolar disorder. Patients with anxiety disorders, ADHD, or depression with anxious ruminations commonly describe their thoughts as “racing.” A good way to distinguish manic racing from anxious racing is to ask:

Were your thoughts racing in a good way or in an unpleasant, worried, or depressed way?

Patients experiencing manic episodes often have a sense of an “accelerated” thought process that is like a joyride in a stolen car. Patients with anxiety or depression will feel very differently.

The activity increase criterion is similar to indiscretion but focuses specifically on the frenetic nature of the activity.

Were you more active than usual?

Were you constantly starting new projects or hobbies?

Did you have so much energy that you felt it was hard to calm down?

Did you need less sleep than usual?

Did you ever stay up all night doing all kinds of things, such as working on projects or calling people?

![]() TIP

TIP

Be careful not to confuse the sleeplessness of depression or anxiety with mania. Patients with mania stay awake because they have so much to think about and do, whereas depressed patients stay awake because they feel tortured by their feelings. Therefore, be sure to ask patients what sorts of things they do when they can’t sleep. Patients with mania will report productive activities, whereas depressed patients will read or watch television as they wait for the solace of sleep.

Did you find it hard to stop talking?

Did other people tell you that they had trouble understanding you?

Did friends have to interrupt you to get a word in edgewise?

Were you using the phone more than usual?

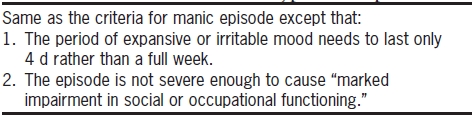

In bipolar disorder, type II, patients have a history of depressive and hypomanic episodes. Hypomania can be hard to diagnose (Table 24.2). Essentially, it amounts to a psychiatric diagnosis for exuberant and often very productive happiness. However, patients with bipolar II spend much of their nonhypomanic time in depression, which is why bipolar II is important not to miss. Use the same DIGFAST questions to diagnose hypomania that are used to diagnose mania. The patient with hypomania will describe definite high periods that have not caused real problems in her life. When hypomanic periods alternate with depressed periods, the proper diagnosis is bipolar, type II disorder.

TABLE 24.2. DSM-5 Criteria for Hypomanic Episode

Data from American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.