29 Assessing Eating Disorders and Somatic Symptom Disorder

Screening Questions

- Eating disorders: Have you ever thought you had an eating disorder, like anorexia or bulimia?

- Somatic symptom disorder: Do you worry a lot about your health?

Eating Disorders

KEY POINT

KEY POINT

Eating disorders are relatively easily diagnosed (Tables 29.1, 29.2, and 29.3). The problem is that many clinicians don’t ask about them, and many sufferers don’t volunteer their symptoms, either because they aren’t bothered by them, as in anorexia, or because they’re too ashamed of them, as in bulimia and binge eating disorder. Therefore, screening questions for eating disorders should always be included in your PROS.

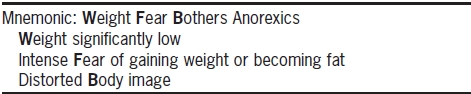

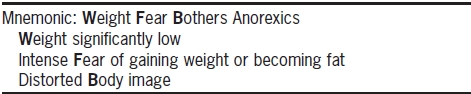

TABLE 29.1. DSM-5 Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa

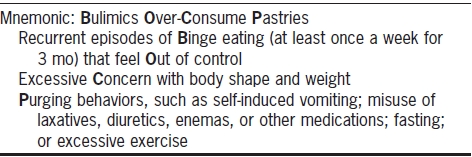

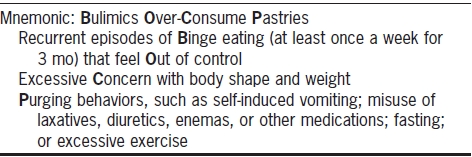

TABLE 29.2. DSM-5 Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa

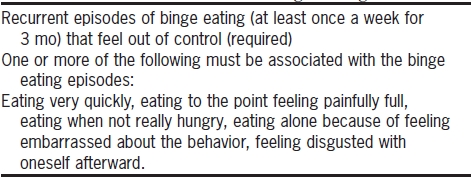

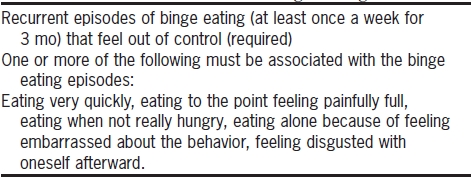

TABLE 29.3. DSM-5 Criteria for Binge Eating Disorder

When time is truly of the essence, you can begin with a direct question:

However, if you have the sense that your patient may be particularly ashamed of a suspected eating disorder, a too blunt approach might endanger the therapeutic alliance. In these cases, you can approach the issue more indirectly:

If the answer is “no,” it is unlikely that your patient has an either anorexia or bulimia. If the answer is yes, and you suspect anorexia, ask:

Almost everyone, and women in particular, has dieted at some point. You’re probing here for a particularly severe diet, perhaps a starvation diet (i.e., fasting) or a diet in which, for example, the patient ate only salad or fruit.

You want to determine what your patient’s lowest body mass index (BMI) was. The BMI is calculated as a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. There are plenty of free online BMI calculators. While DSM-IV required that a patient’s weight be no more than 85% of the ideal body weight to qualify for anorexia, that’s no longer the case with DSM-5. Instead, there are suggested BMI benchmarks to help you to judge the severity of the disorder, which are printed in the DSM-5.

Anorexic patients will report feeling overweight, even obese, at a weight that is far below their ideal weight. Often, the patient will fixate on a particular body part, such as the thighs or the stomach.

For both bulimia and binge eating disorder (BED), good screening questions are:

TIP

TIP

You have to be somewhat skeptical of a “yes” answer, because what the patient considers a binge may seem like a normal meal to someone else. Ask your patient to describe the contents of a typical binge and decide whether it seems like an unusually large meal.

If she binges, ask if she has ever purged afterward.

Establish the frequency of the behavior with a symptom exaggeration question:

If the patient has binged but has never purged, then you should ask some or all of the following questions to rule in or out BED.

Somatic Symptom Disorder and Illness Anxiety Disorder

In DSM-IV, somatization disorder, or hypochondriasis, was used to diagnose patients who worried excessively about multiple somatic symptoms—which were medically unexplained. DSM-5 has abolished somatization disorder, substituting two different diagnoses, which differ in subtle ways:

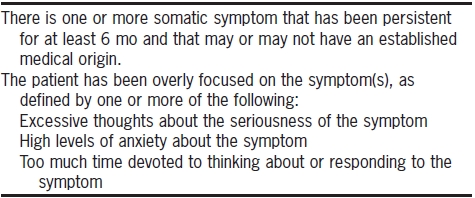

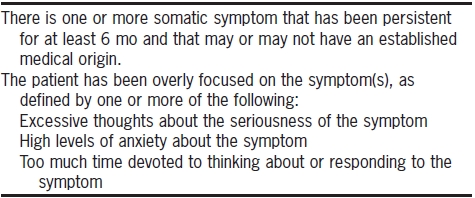

Somatic symptom disorder (SSD) refers to people who have actual somatic symptoms (which may or may not be caused by an established medical problem) but who are so excessively preoccupied with the symptoms that they have problems functioning (Table 29.4).

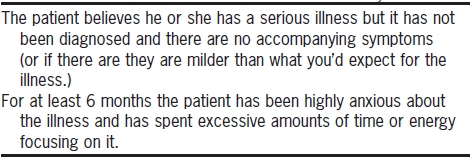

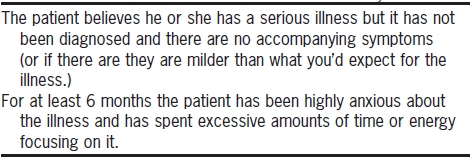

Illness anxiety disorder refers to people who do not actually have somatic symptoms but who are extremely worried that they have an illness—in the absence of any medical evidence that they do (Table 29.5).

TABLE 29.4. DSM-5 Criteria for Somatic Symptom Disorder

For either disorder, an excellent screening question is

If the patient says “no,” you can avoid the probing questions. If he says yes, proceed as below. In truth, a patient with either disorder will have likely already hinted at the problem when you elicited the history of present illness (HPI), much of which will have been devoted to discussions of health issues.

Your next job is to determine if there are any actual symptoms.

The patient with SSD will launch into a list of somatic symptoms, like pain, fatigue, diarrhea, palpitations, and the like. On the other hand, the patient with anxiety illness disorder will not provide much information about specific symptoms and will instead say something like: “It’s pretty vague, I just know I’m sick and I’m pretty sure it’s cancer.”

As you can see, it can be hard to differentiate between these two conditions. Generally, patients who used to qualify for “somatization disorder” (which required at least seven discrete somatic symptoms) will likely be diagnosed with new disorder, SSD. Patients with the new illness anxiety disorder may describe some symptoms as well, but the symptoms will be described more vaguely and there won’t be as many of them.

The somatic disorders were reorganized in this way not in order to confuse us—though that will surely happen. The major impetus was to remove some of the stigma that has become attached to somatization disorder and the derogatory label “hypochondriac.” Such patients are often made to feel that their symptoms are “all in their head,” when in fact they actually do perceive symptoms, along with an overlay of anxiety that makes the symptoms feel worse.

TABLE 29.5. DSM-5 Criteria for Illness Anxiety Disorder

![]() KEY POINT

KEY POINT