HOW SCIENCE WORKS

The development of critical thinking over many centuries led to a paradigm shift in human thought and history: the scientific revolution. Without its development and practice in cities like Florence, Bologna, Göttingen, Paris, London, and Edinburgh, to name just a handful of great centers of learning, science may not have come to shape our culture, industry, and greatest ambitions as it has. Science is not infallible, of course, but scientific thinking underlies a great deal of what we do and of how we try to decide what is and isn’t so. This makes it worth taking a close look behind the curtain to better see how it does what it does. That includes seeing how our imperfect human brains, those of even the most rigorous thinkers, can fool themselves.

Unfortunately, we must also recognize that some researchers make up data. In the most extreme cases, they report data that were never collected from experiments that were never conducted. They get away with it because fraud is relatively rare among researchers and so peer reviewers are not on their guard. In other cases, an investigator changes a few data points to make the data more closely reflect his or her pet hypotheses. In less extreme cases, the investigator omits certain data points because they don’t conform to the hypothesis, or selects only cases that he or she knows will contribute favorably to the hypothesis. A case of fraud occurred in 2015 when Dong-Pyou Han, a former biomedical scientist at Iowa State University in Ames, was found to have fabricated and falsified data about a potential HIV vaccine. In an unusual outcome, he didn’t just lose his job at the university but was sentenced to almost five years in prison.

The entire controversy about whether the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine causes autism was propagated by Andrew Wakefield in an article with falsified data that has now been retracted—and yet millions of people continue to believe in the connection. In some cases, a researcher will manipulate the data or delete data according to established principles, but fail to report these moves, which makes interpretation and replication more difficult (and which borders on scientific misconduct).

The search for proof, for certainty, drives science, but it also drives our sense of justice and all our judicial systems. Scientific practice has shown us the right way to proceed with this search.

There are two pervasive myths about how science is done. The first is that science is neat and tidy, that scientists never disagree about anything. The second is that a single experiment tells us all we need to know about a phenomenon, that science moves forward in leaps and bounds after every experiment is published. Real science is replete with controversy, doubts, and debates about what we really know. Real scientific knowledge is gradually established through many replications and converging findings. Scientific knowledge comes from amassing large amounts of data from a large number of experiments, performed by multiple laboratories. Any one experiment is just a brick in a large wall. Only when a critical mass of experiments has been completed are we in a position to regard the entire wall of data and draw any firm conclusions.

The unit of currency is not the single experiment, but the meta-analysis. Before scientists reach a consensus about something, there has usually been a meta-analysis, tying together the different pieces of evidence for or against a hypothesis.

If the idea of a meta-analysis versus a single experiment reminds you of the selective windowing and small sample problems mentioned in Part Two, it should. A single experiment, even with a lot of participants or observations, could still just be an anomaly—that eighty miles per gallon you were lucky to get the one time you tested your car. A dozen experiments, conducted at different times and places, give you a better idea of how robust the phenomenon is. The next time you read that a new face cream will make you look twenty years younger, or about a new herbal remedy for the common cold, among the other questions you should ask is whether a meta-analysis supports the claim or whether it’s a single study.

Deduction and Induction

Scientific progress depends on two kinds of reasoning. In deduction, we reason from the general to the specific, and if we follow the rules of logic, we can be certain of our conclusion. In induction, we take a set of observations or facts, and try to come up with a general principle that can account for them. This is reasoning from the specific to the general. The conclusion of inductive reasoning is not certain—it is based on our observations and our understanding of the world, and it involves a leap beyond what the data actually tell us.

Probability, as introduced in Part One, is deductive. We work from general information (such as “this is a fair coin”) to a specific prediction (the probability of getting three heads in a row). Statistics is inductive. We work from a particular set of observations (such as flipping three heads in a row) to a general statement (about whether the coin is fair or not). Or as another example, we would use probability (deduction) to indicate the likelihood that a particular headache medicine will help you. If your headache didn’t go away, we could use statistics (induction) to estimate the likelihood that your pill came from a bad batch.

Induction and deduction don’t just apply to numerical things like probability and statistics. Here is an example of deductive logic in words. If the premise (the first statement) is true, the conclusion must be also:

Gabriel García Márquez is a human.

All humans are mortal.

Therefore (this is the deductive conclusion) Gabriel García Márquez is mortal.

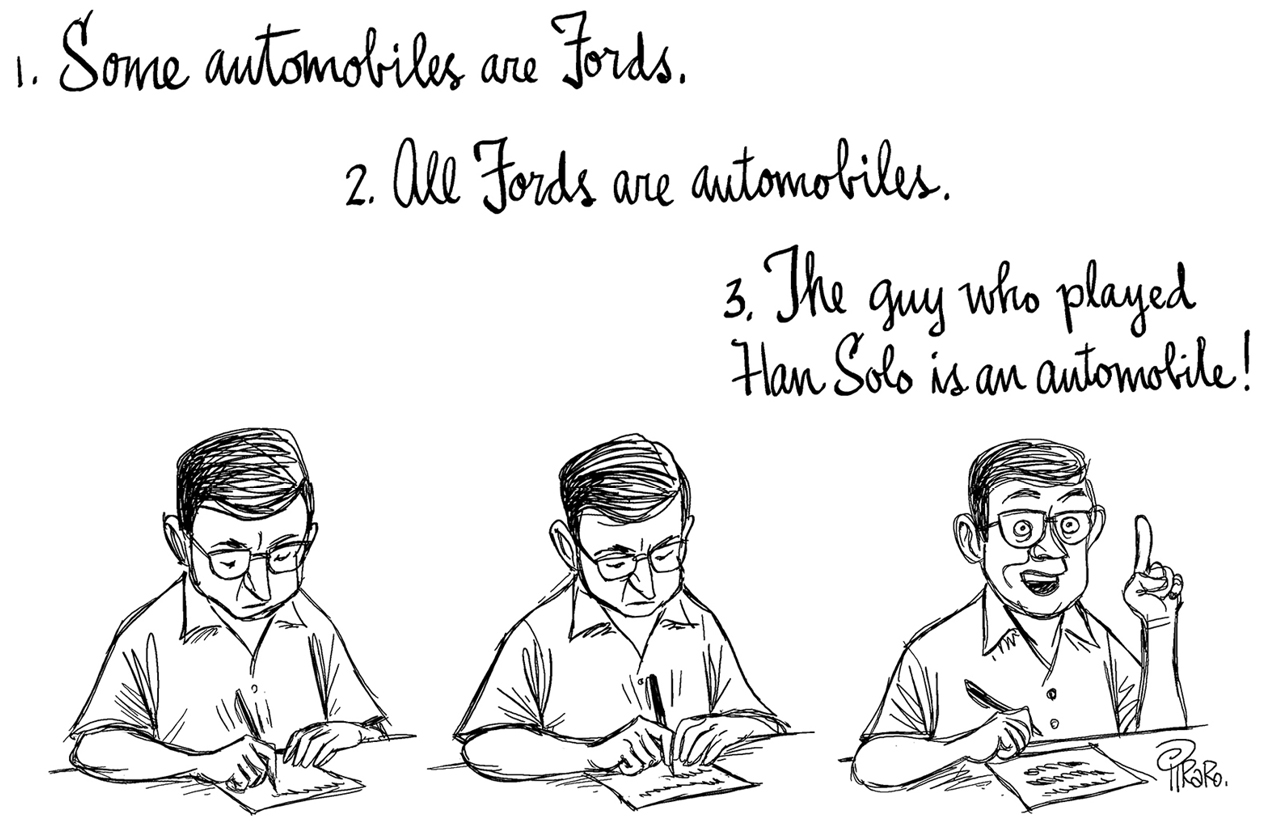

The type of deductive argument about Márquez is called a syllogism. In syllogisms, it is the form of the argument that guarantees that the conclusion follows. You can construct a syllogism with a premise that you know (or think to be) false, but that doesn’t invalidate the syllogism—in other words, the logic of the whole thing still holds.

The moon is made of green cheese.

Green cheese costs $22.99 per pound.

Therefore, the moon costs $22.99 per pound.

Now, clearly the moon is not made of green cheese, but IF it were, the deduction is logically valid. If it makes you feel better, you can rewrite the syllogism so that this is made explicit:

IF the moon is made of green cheese

AND IF green cheese costs $22.99 per pound

THEN the moon costs $22.99 per pound.

There are several distinct types of deductive arguments, and they’re typically taught in philosophy or math classes on formal logic. Another common form involves conditionals. This one is called modus ponens. It’s easy to remember what it’s called with this example (using Poe as in ponens):

If Edgar Allan Poe went to the party, he wore a black cape.

Edgar Allan Poe went to the party.

Therefore, he wore a black cape.

Formal logic can take some time to master, because, as with many forms of reasoning, our intuitions fail us. In logic, as in running a race, order matters. Does the following sound like a valid or invalid conclusion?

If Edgar Allan Poe went to the party, he wore a black cape.

Edgar Allan Poe wore a black cape.

Therefore, he went to the party.

While it might be true that Poe went to the party, it is not necessarily true. He could have worn the cape for another reason (perhaps it was cold, perhaps it was Halloween, perhaps he was acting in a play that required a cape and wanted to get in character). Drawing the conclusion above represents an error of reasoning called the fallacy of affirming the consequent, or the converse error.

If you have a difficult time remembering what it’s called, consider this example:

If Chuck Taylor is wearing Converse shoes, then his feet are covered.

Chuck Taylor’s feet are covered.

Therefore, he is wearing Converse shoes.

This reasoning obviously doesn’t hold, because wearing Converse shoes is not the only way to have your feet covered—you could be wearing any number of different shoe brands, or have garbage bags on your feet, tied around the ankles.

However, you can say with certainty that if Chuck Taylor’s feet are not covered, he is not wearing Converse shoes. This is called the contrapositive of the first statement.

Logical statements don’t work like the minus signs in equations—you can’t just negate one side and have it automatically negate the other. You have to memorize these rules. It’s somewhat easier to do using quasi-mathematical notation. The statements above can be represented this way, where A stands for any premise, such as “If Chuck Taylor is wearing Converse shoes,” or “If the moon is made of green cheese” or “If the Mets win the pennant this year.” B is the consequence, such as “then Chuck’s feet are covered,” or “then the moon should appear green in the night sky” or “I will eat my hat.”

Using this generalized notation, we say If A as a shorthand for “If A is true.” We say B or Not B as a shorthand for “B is true” or “B is not true.” So . . .

If A, then B

A

Therefore, B

In logic books, you may see the word then replaced with an arrow (→) and you may see the word not replaced with this symbol: ~. You may see the word therefore replaced with ∴ as in:

If A → B

A

∴ B

Don’t let that disturb you. It’s just some people trying to be fancy.

Now there are four possibilities for statements like this: A can be true or not true, and B can be true or not true. Each of the possibilities has a special name.

1. Modus ponens. This is also called affirming the antecedent. “Ante” means before, like when you “ante up” in poker, putting money in the pot before any cards are played.

If A → B

A ∴ B

Example: If that woman is my sister, then she is younger than I am.

That woman is my sister.

Therefore, she is younger than I am.

2. The contrapositive.

If A → B

~ B ∴ ~ A

Example: If that woman is my sister, then she is younger than I am.

That woman is not younger than I am.

Therefore, she is not my sister.

3. The converse.

If A → B

B ∴ A

This is a not a valid deduction.

Example: If that woman is my sister, then she is younger than I am.

That woman is younger than I am.

Therefore, she is my sister.

This is invalid because there are many women younger than I am who are not my sister.

4. The inverse.

If A → B

~A ∴ ~B

This is a not a valid deduction.

Example: If that woman is my sister, then she is younger than I am.

That woman is not my sister.

Therefore, she is not younger than I am.

This is invalid because many women who are not my sister are still younger than I am.

Inductive reasoning is based on there being evidence that suggests the conclusion is true, but does not guarantee it. Unlike deduction, it leads to uncertain but (if properly done) probable conclusions.

An example of induction is:

All mammals we have seen so far have kidneys.

Therefore (this is the inductive step), if we discover a new mammal, it will probably have kidneys.

Science progresses by a combination of deduction and induction. Without induction, we’d have no hypotheses about the world. We use it all the time in daily life.

Every time I’ve hired Patrick to do a repair around the house, he’s botched the job.

Therefore, if I hire Patrick to do this next repair, he’ll botch this one too.

Every airline pilot I’ve met is organized, conscientious, and meticulous.

Lee is an airline pilot. He has these qualities, and he’s also good at math.

Therefore, all airline pilots are good at math.

Of course, this second example doesn’t necessarily follow. We’re making an inference. With what we know about the world, and the job requirements for being a pilot—plotting courses, estimating the influence of wind velocity on arrival time, etc.—this seems reasonable. But consider:

Every airline pilot I’ve met is organized, conscientious, and meticulous.

Lee is an airline pilot. He has these qualities, and he also likes photography.

Therefore, all airline pilots like photography.

Here our inference is less certain. Our real-world knowledge suggests that photography is a personal preference, and it doesn’t necessarily follow that a pilot would enjoy it more or less than a non-pilot.

The great fictional detective Sherlock Holmes draws conclusions through clever reasoning, and although he claims to be using deduction, in fact he’s using a different form of reasoning called abduction. Nearly all of Holmes’s conclusions are clever guesses, based on facts, but not in a way that the conclusion is airtight or inevitable. In abductive reasoning, we start with a set of observations and then generate a theory that accounts for them. Of the infinity of different theories that could account for something, we seek the most likely.

For example, Holmes concludes that a supposed suicide was really a murder:

HOLMES: The wound was on the right side of his head. Van Coon was left-handed. Requires quite a bit of contortion.

DETECTIVE INSPECTOR DIMMOCK: Left-handed?

HOLMES: Oh, I’m amazed you didn’t notice. All you have to do is look around this flat. Coffee table on the left-hand side; coffee mug handle pointing to the left. Power sockets: habitually used the ones on the left . . . Pen and paper on the left-hand side of the phone because he picked it up with his right and took down messages with his left . . . There’s a knife on the breadboard with butter on the right side of the blade because he used it with his left. It’s highly unlikely that a left-handed man would shoot himself in the right side of his head. Conclusion: Someone broke in here and murdered him . . .

DIMMOCK: But the gun . . . why—

HOLMES: He was waiting for the killer. He’d been threatened.

Note that Sherlock uses the phrase highly unlikely. This signals that he’s not using deduction. And it’s not induction because he’s not going from the specifics to the general—in a way, he’s going from one set of specifics (the observations he makes in the victim’s flat) to another specific (ruling it murder rather than suicide). Abduction, my dear Watson.

Arguments

When evidence is offered to support a statement, these combined statements take on a special status—what logicians call an argument. Here, the word argument doesn’t mean a dispute or disagreement with someone; it means a formal logical system of statements. Arguments have two parts: evidence and a conclusion. The evidence can be one or more statements, or premises. (A statement without evidence, or without a conclusion, is not an argument in this sense of the word.)

Arguments set up a system. We often begin with the conclusion—I know this sounds backward, but it’s how we typically speak; we state the conclusion and then bring out the evidence.

Conclusion: Jacques cheats at pool.

Evidence (or premise): When your back was turned, I saw him move the ball before taking a shot.

Deductive reasoning follows the process in the opposite direction.

Premise: When your back was turned, I saw him move the ball before taking a shot.

Conclusion: Jacques cheats at pool.

This is closely related to how scientists talk about the results of experiments, which are a kind of argument, again in two parts.

Hypothesis = H

Implication = I

H: There are no black swans.

I: If H is true, then neither I nor anyone else will ever see a black swan.

But I is not true. My uncle Ernie saw a black swan, and then took me to see it too.

Therefore, reject H.

A Deductive Argument

The germ theory of disease was discovered through the application of deduction. Ignaz Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician who conducted a set of experiments (twelve years before Pasteur’s germ and bacteria research) to determine what was causing high mortality rates at a maternity ward in the Vienna General Hospital. The scientific method was not well established at that point, but his systematic observations and manipulations helped not only to pinpoint the culprit, but also to advance scientific knowledge. His experiments are a model of deductive logic and scientific reasoning.

Built into the scenario was a kind of control condition: The Vienna General had two maternity wards adjacent to each other, the first division (with the high mortality rate) and the second division (with a low mortality rate). No one could figure out why infant and mother death rates were so much higher in one ward than the other.

One explanation offered by a board of inquiry was that the configuration of the first division promoted psychological distress: Whenever a priest was called in to give last rites to a dying woman, he had to pass right by maternity beds in the first division to get to her; this was preceded by a nurse ringing a bell. The combination was believed to terrify the women giving birth and therefore make them more likely victims of this “childbed fever.” The priest did not have to pass by birthing mothers in the second division when he delivered last rites because he had direct access to the room where dying women were kept.

Semmelweis proposed a hypothesis and implication that described an experiment:

H: The presence of the ringing bell and the priest increases chances of infection.

I: If the bell and priest are not present, infection is not increased.

Semmelweis persuaded the priest to take an awkward, circuitous route to avoid passing the birthing mothers of the first division, and he persuaded the nurse to stop ringing the bell. The mortality rate did not decrease.

I is not true.

Therefore H is false.

We reject the hypothesis after careful experimentation.

Semmelweis entertained other hypotheses. It wasn’t overcrowding, because, in fact, the second division was the more crowded one. It wasn’t temperature or humidity, because they were the same in the two divisions. As often happens in scientific discovery, a chance event, purely serendipitous, led to an insight. A good friend of Semmelweis’s was accidentally cut by the scalpel of a student who had just finished performing an autopsy. The friend became very sick, and the subsequent autopsy revealed some of the same signs of infection as were found in the women who were dying during childbirth. Semmelweis wondered if there was a connection between the particles or chemicals found in cadavers and the spread of the disease. Another difference between the two divisions that had seemed irrelevant now suddenly seemed relevant: The first division staff were medical students, who were often performing autopsies or cadaver dissections when they were called away to deliver a baby; the second division staff were midwives who had no other duties. It was not common practice for doctors to wash their hands, and so Semmelweis proposed the following:

H: The presence of cadaverous contaminants on the hands of doctors increases chances of infection.

I: If the contaminants are neutralized, infection is not increased.

• • •

Of course, an alternative I was possible too: If the workers in the two divisions were switched (if midwives delivered in division one and medical students in division two) infection would be decreased. This is a valid implication too, but for two reasons switching the workers was not as good an idea as getting the doctors to wash their hands. First, if the hypothesis was really true, the death rate at the hospital would remain the same—all Semmelweis would have done was to shift the deaths from one division to another. Second, when not delivering babies, the doctors still had to work in their labs in division one, and so there would be an increased delay for both sets of workers to reach mothers in labor, which could contribute to additional deaths. Getting the doctors to wash their hands had the advantage that if it worked, the death rate throughout the hospital would be lowered.

Semmelweis conducted the experiment by asking the doctors to disinfect their hands with a solution containing chlorine. The mortality rate in the first division dropped from 18 percent to under 2 percent.