For (Jane Austen and the readers of Pride and Prejudice), as for Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth Bennett’s solitary walks express the independence that literally takes the heroine out of the social sphere of the houses and their inhabitants, into a larger, lonelier world where she is free to think: walking articulates both physical and mental freedom.

— Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

From the beginning of the car age, cars have been marketed to us as tickets to freedom. In our own cars, we can choose our individual path and get to our destination quickly, unimpeded by the inconvenience/lack of speed of walking or public transportation. There is no point in denying the truth of that scenario — all things being equal, getting in a car affords tremendous mobility. In a car, not only are we not limited to destinations reachable only by foot, bike, bus or train, but cars allow us to choose our own route and set our own schedule.

The problem, however, is that all things are no longer equal. Car ownership began to become ubiquitous in the 1950s. Since then, we have revolutionized the ways in which our cities are planned and built. Caught up in the allure of the car age, we remade our places, and built new ones, that cater to cars. Today we often forget that prior to World War II, every city in America was built for easy walking and biking. In fact, the idea of living in a walkable place is nothing radical. What was radical was the program we undertook to build an entirely new type of human life. We built networks of roadways and freeways like nothing any society had ever seen before. We tore down entire neighborhoods to accommodate these roads as well as the parking lots and garages required by the cars that would travel these roads; at the same time, we ripped out the tracks for streetcars and trains.

As we became drunk on cars and the modern age, we forgot some basic things about human nature. One of our core characteristics is that we crave freedom and choices.

I have more freedom because I live in a walkable neighborhood.

Writing this book in 2013 and looking back several decades, it’s apparent that our society has come full circle in terms of the freedom of mobility. Where the car once provided freedom from the crowded, old city, it now is a device that enslaves us. Yes, I do mean enslaved.

Like many people my age and younger, when I was growing up, we used a car to get around everywhere; I was barely aware that there was any way to live that wasn’t entirely car reliant. For about three generations now, Americans have grown up fully immersed in the car culture, not knowing alternatives — and that’s a problem.

The problem, at its most basic, is that we have become dependent on cars. While cars were once a ticket to freedom, we are now hostages to our cars. Most of our cities and towns are such that we need a car to survive. We need a car to get food, to access decent housing, to find employment, to get to our workplaces and to entertain ourselves. If we don’t have a car, or don’t have access to one, we feel trapped, even helpless.

Most of us are all too familiar with that feeling. For me, one teenage incident in particular stands out. As a reckless sixteen-year-old, I drove my old Chevy Impala to the high school parking lot one night and did donuts until the engine died. I had to get it jumped by my parents, who were so upset, they took away my keys for a week. At the time, it felt like a social death sentence. How could I possibly have a life if I didn’t have my car?

Perhaps you can remember a time in your life when you didn’t have a car. Did your car break down and you couldn’t afford to fix it right away? Or was it in the shop for a few days? Did you injure yourself in a way that prevented you from driving? Did you lose a job and just couldn’t afford a car?

It’s for all these reasons and more that I love walking and choose to live in a walkable neighborhood. Because I am not dependent on my car, I have more freedom of movement than the average American. I’m never trapped at my house or apartment because of a car problem. If my car breaks down, I can still walk, ride a bike or take public transportation very easily to everywhere I need to go. I might even decide not to fix the car for a while, since I rarely need it urgently. As someone who was raised in pretty typical suburban environments, it’s hard to describe just how empowering this freedom feels.

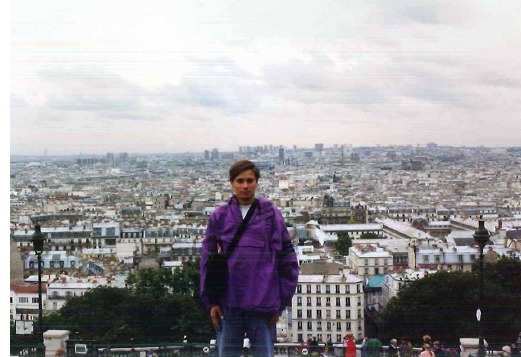

A formative time for me in terms of beginning to change my views on car reliance was a summer spent in Paris. In 1993, as an undergraduate studying architecture, I went to Paris on a summer program. As students, we lived for most of the summer at the International University on the edge of the city center, just off the Boulevard Jourdan. Even without living in the heart of Paris, it was amazing to experience just how freeing it was to not need a car. Of course, we could rent a car if we wanted to (and we did, for one road trip), but we didn’t need one for anything we did those six weeks. That forced experience of living a different way truly opened my eyes. Upon returning home, I honestly felt depressed at the lifestyle options presented to me.

But, as I argue throughout these pages, our lifestyle options are broader than we may think. My experience was twenty years ago, and much has changed since then. American cities and towns have begun a rebirth, working to recapture some of the character they had a century ago, when people routinely traveled by foot. Some places are much further along in that process than others, but from coast to coast, this recognition of the importance of walkability has been a very encouraging phenomenon. Our communities increasingly allow us to walk to many destinations and experience a sense of the freedom I enjoyed in Paris. I found such a place in Savannah, Georgia. There are many others. And even if you don’t live in a walkable place and are not about to pick up and move, there are still ways to incorporate more walking into your life — it just takes some creativity. Try it out for a time and experience the freedom that comes with more transportation choices.

Vive la France!

I can actually (gasp!) eliminate my car if I so desire.

I grew up with cars, and for years I looked forward to the day when I’d own a car of my own. As a teenager in Marshall, Missouri, there was nothing I wanted more than the freedom I thought a car would provide. I was raised on the idea of “cruising” as a fun activity, on my family’s long road trips by car around the country, and on the notion that, on some level, our cars are an extension of who we are. Even when my friends and I were young and didn’t have any money, we talked endlessly about what kind of beater we’d buy and how we would trick it out.

Feeling as if our cars defined us was not exclusive to young men. For many women of my generation and older, owning their own car was a way of establishing their place in the world, an expression of their independence from men. A good friend from high school, Renee Gentry, describes it this way: “Remember the Blue Bomber? My blue 1977 Chevy Impala with the ‘upgraded’ cassette deck? Nice. It was freedom. For me it was freedom in three significant ways: as a woman, as the youngest child and as a ‘country kid.’ I could listen to music I chose, not something picked by my older brother or sister. I had shared a room my whole life up to that point. This was the first thing I didn’t have to share. I didn’t have to rely on a ‘date’ to pick me up. I could literally ‘go to town’ and that meant I could get a job. It also meant, in my mind, that I could go to college someplace else.”

Freedom, as defined by a teenager in 1987.

Given my history, the idea that I could potentially not have a car at all is, well, a little foreign and maybe even a little frightening. When I consider flat-out eliminating a car from my life, it feels a bit like I would be cutting off a limb. Even though I don’t rely on it much anymore, there’s a certain security in knowing it’s there as an option. That’s my context.

But as I age, and as I enjoy living a walkable life more and more, the idea of not having a car is becoming increasingly appealing in certain ways. I now run scenarios in my head of how it would work, given my own travel patterns and my day-to-day life. How would I get to Target, for my occasional trip there? How about the beach or the movies? Would I take cabs to the airport?

The reality is that I have a choice. Should I want to sell my car and live without one, I can quite easily go on with my life and hardly notice a car’s absence. I’m fortunate that for many of my daily needs, I can very easily walk or ride a bike. For longer or irregular trips, I could ride the bus or take cabs. I could even rent a car, should I want one for a day or more.

And there are still more possibilities for the car-less. The “sharing economy” is quickly expanding the options at my disposal. Car sharing, once available primarily in Europe and the largest cities in the United States, is quickly becoming an option in many more cities. Savannah doesn’t have car sharing yet, but likely will within the next couple of years given how quickly it’s catching on nationwide. Car sharing would allow me to have all the benefits of having a car when I need one without the hassles of owning one. And since I don’t need a car very often, car sharing holds a good deal of appeal.

A great side benefit of living in a walkable place is that it’s the kind of place where services like car sharing (and bike sharing, for that matter) make the most sense. Since members need to get to a location where the shared vehicles are, which they generally do by walking, it helps to have those locations in walkable places. And since people who live in such places tend to own fewer cars and drive less, sharing vehicles better serves their needs than individual ownership. As our society continues to transition out of what I believe are the latter years of the car culture, it will be interesting to see how the “sharing economy” changes how we live.

Can the kid who grew up desperately wanting a car actually live without one? Increasingly, the answer is yes.

I can take the bus, and no, it’s not scary.

Let’s be honest. For the majority of Americans, the bus is something we think only poor people use. They use it because they have to. And most likely, they do so because they can’t afford a car. That’s our impression. We feel badly for people riding the bus.

Like most stereotypes, there’s a strong element of truth to this belief. Given how most of us have been raised (on the virtues of the car culture), the bus seems like a terrible alternative. I know that when I was a teenager, I couldn’t wait to stop taking the bus to school and couldn’t imagine choosing to use one as an adult.

Let’s start with the negatives. Buses can in fact have seats that are a little too close to each other and be full of creepy-seeming people who don’t smell great. The ride can bounce you around, and the driver may start and stop abruptly. The payment systems are often confusing. As for the routes, if you can quickly figure out where the buses are going and when by looking at signs on the street, then you’re much more street-smart than most. So now that I’ve painted such a pretty picture, why would I suggest that taking the bus is a good thing?

Taking the bus is a little bit like eating brown rice or drinking fresh vegetable juice. We may not really like it at first, but it’s good for us and we get used to it. Eventually, we might even enjoy it. One might say that taking the bus is an acquired taste. Every once in a while, I find myself taking the bus to downtown destinations in Savannah, either because of weather or my own laziness. I walk a few blocks to the stop and generally wait a few minutes for one to arrive. While the routes still seem bewildering at times, it’s almost always a quick and easy trip that would otherwise take me thirty minutes or more to walk. Sometimes I even get a bonus of a good story to share with friends.

Bus systems can be confusing, and they can be a pain. But there are also a few pretty good things about the bus. They’re hot in the winter and cold in the summer. They’re an inexpensive way to go a long distance. Bus riders don’t have to deal with parking, which is a notable benefit in some destinations. And because you’re not behind the wheel, once you’re on the bus you don’t have to do a thing except sit back. When it’s a longer trip, you can even read or watch movies. Oh by the way, you’re also likely paying for the bus already with your tax dollars, so there’s the financial element as well.

The same arguments can be made for trains, from streetcars to light rail to long-distance trains. As with buses, part of the joy of the train is removing the stress of driving and freeing up your time to do something else.

The good news is that smart people are working to make riding the bus a much better experience. Bus systems are adding services that are more reliable and upscale. If you have a smartphone, you can pretty easily access bus schedules on it. Google Maps incorporates bus routes into its mapping, which is pretty cool. And many cities are redesigning their bus systems so that they are much more easily understood and go where people need them to go.

All this is well and good if getting to the bus is convenient for you, which typically means living in a walkable place. Since every bus trip presumably starts and ends with walking to the bus stop or having someone drop you off, getting to the bus is much more difficult if you live somewhere built for cars. The streets are filled with fast-moving traffic, and there may not even be any sidewalks. Walkable places have better bus service because they are walking places first — and because there are just more people to begin with.

So if you’re one of the many who harbor negative views about riding the bus, know that you can change. I have — now I ride the bus on a regular basis. I doubt most of us will ever really love the bus. But hey, a little grilled chicken and vegetables over brown rice isn’t such a bad idea once in a while.

OK, so I don’t have kids. But if I did, I’d love for them to live in a walkable place and to be walkers like me. I’ve talked at length about how freedom of movement is a benefit to me, and I’ll discuss some of the social and other benefits later. That same freedom is also available to children, especially those who are old enough to get out and about on their own.

Just think of some of the simple ways that life is better for both parents and kids in a walkable place. If there’s a school in the neighborhood, they can walk to school (and home). They don’t need me to drive them to the park, or to a store or to their friends’ houses. They can even go to the store to get groceries for me, as kids did generations ago.

Those benefits may sound ridiculous or even terrifying to a lot of parents out there. Don’t we live in a big, scary world with lots of crazy people? Why on earth would you want your kids out wandering around unsupervised? It is unfortunate that we live in a time and in places where horrible things can happen, and sometimes they happen to children. And it is absolutely true the world has its share of creepy and dangerous people.

But if we step back and review actual data, the statistics indicate that the things we most fear are very rare, and, in fact, the instances of violence against children have been growing less and less common. It often doesn’t seem that way because our news media is so pervasive. When crime happens anywhere, it’s very quickly national news. The attention and hype given to every singular event plays to our deepest irrational fears and has us asking, “Can that happen here?”

Look, life can be scary at times. But if we succumb to our fears, we give up the joys and pleasures of life, and that translates to our kids as well. Where once we allowed kids to play outside with abandon, we now confine them to only certain approved activities and locations. Where once it was common to walk to school, it’s now the norm to be driven to school. When I was in elementary school, for example, after-school time often included walking along with friends to someone’s house and impromptu games or goofing around. Today, parents who allow their kids that kind of freedom are almost considered neglectful. Instead, we somehow think it’s safer and better to pile kids in the car, chauffeur them around and get them quickly to the house and backyard, or the supervised sports activity.

When considering safety, there are additional factors to keep in mind when thinking about turning kids, or even adults, loose. Walkable places tend to have qualities that law enforcement personnel actually prefer because those places are safer. What are those qualities? For starters, more people on the street tend to mean more witnesses, which is generally a deterrent to crime. And in places that are best for walking, the houses typically open up to the front, often with attractive porches and stoops. The people who sit on those porches become “eyes on the street,” helping to reinforce the safety of a place.

In fact, what we often don’t think about is that the most dangerous places for kids are those places where they spend a lot of time: in cars. More children die from injuries in car accidents than anything else. That’s true for every age group except those under a year old. Car accidents kill more kids than disease, birth defects or homicide. And millions more children are injured in car accidents. The National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health have documented the top causes of death for children and adolescents at this website: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001915.htm.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Beyond the safety issue, having more mobility and independence is better for child development. Kids need to be able to expand their world in ways beyond the video games in the basement. Sociability is incredibly important for children to learn at a young age, and the only good way to learn it is by meeting a wide variety of people in the course of daily life. That’s far easier for kids to do when they can get out and walk around, or ride a bike around safely, than if they’re stuck on a cul-de-sac waiting for their parents to take them somewhere.

Mobility is important for all of us, not just those of us who have the choice of driving. Kids want to explore their world. We need to make it easier for them to do so.

One of my favorite parts of the newspaper when I was younger was a small weekly article in which people wrote about their experiences as children growing up in Kansas City in the decades from the 1910s through the 1960s. Part of what struck me was how fondly and readily they talked about taking the streetcars with their friends, without adult supervision. They would walk alone or with friends to the neighborhood store or ride a bike to the park. Kids a century ago had much more freedom than kids today. The National Center for Safe Routes to School reported on this in its November, 2011 study, “How Children Get to School.” The study found that even as recently as 1969, forty-eight percent of all kids walked to school. Now only thirteen percent do.

We all have fears about our world. It’s unfortunate that this fear has caused us to give up so much. Childhood adventures are precious, and they are necessary for developing a sense of independence and engagement with the world. Not only does childhood independence help with sociability, it also builds confidence and self-esteem. As we rediscover walking, I hope we can find a way to make it a kids’ paradise as well.

If I want to extend my reach, it’s easy to hop on a bike to get farther.

When I was a kid in Albert Lea, Minnesota, the bike was my primary means of getting around — once I was too big for a Big Wheel, that is. I loved getting on my bike and riding to friends’ houses, parks, lakes and other destinations. I was fortunate that I lived in a small town where biking was easy and safe, in no small part because there was a large network of bike trails and bike routes.

As an adult, I still enjoy biking. My bike now is considerably more expensive and fancy, but it serves the same purpose — it further enhances and facilitates my experience of getting around without a car. And, not to put too fine a point on it, but biking in a bike-friendly city is a lot more fun than driving.

I like to be as honest as I can — both with myself and others — about what it’s really like to be less car-dependent. I do love to walk, and I can often walk to quite a few daily destinations. But let’s face it — some places are far away, some days I just don’t feel like it, and some days the weather isn’t great. On occasion, I’ll hop in my car to take care of what I need to. But at other times, the bike is great for getting somewhere a lot faster than I can on foot.

The places that I most often go on a daily basis are generally within about a mile of where I live. With a bike, it’s very easy to stretch that to two, three or even five miles.

For years, we’ve neglected the potential of biking as a viable transportation method. While many European nations have taken great strides in making biking comfortable and a viable option for everyone, we’ve tended to accommodate only the most avid cyclists. You’ve seen them, right? Wearing brightly colored, tight-fitting (sometimes too tight) clothes, the true warriors on bikes will ride anywhere, in any kind of condition. They spend a lot of money and time on the bike, doing routine rides of fifty or one hundred miles.

Good for them. But that’s not me.

And, frankly, bike warriors are only a very small percentage of the US population. Cycling experts I work with tell me only one to three percent of the public are avid cyclists. Most of us fall into the large category of “interested, but concerned.” By that, they mean we are interested in the idea of biking more, but concerned about safety, cost, road conditions, locking the bike, etc.

The good news is that our cities and towns are getting better at addressing our concerns. Programs such as bike sharing are on the rise, which make it easy to ride even if you don’t own a bike. Physical improvements like cycle tracks and off-street bike paths are going well beyond the sad-looking bike lanes that were the first-generation efforts to accommodate cyclists. More cities are adding bike parking areas and bike racks that make it harder to steal a bike.

Like many of the subjects addressed in this book, the world of biking is looking brighter. For me, biking is just one more way to explore my world, get to where I need to go, and save a few bucks in the process. I’d also mention the exercise benefits, but that’s for a later chapter. One of the best parts is that all those years of riding a bike as a kid have not gone to waste. It really is easy to pick it up again and remember the fun you had from long-gone days.

I have a lot of different options for my routes.

“Variety’s the very spice of life, that gives it all its flavour,” wrote the poet William Cowper. And Robert Frost wrote, “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I — I took the one less traveled by. And that has made all the difference.”

Both of these men speak to something deep within us as human beings. We like to have options. Options are good. Choices are good. Having choices in all matters of life feeds our senses of self and freedom.

I often hear people talk about making a place more walkable, and they start by complaining of a lack of sidewalks. That’s a good place to begin, but it doesn’t rate nearly as important as two other factors that I am able to benefit from every day in my neighborhood. One is the availability of destinations worth walking to. And the second is a wide variety of routes that I can take to get there.

The first item is obvious. If we don’t have interesting places to walk to, our desire to walk is dramatically reduced. We may enjoy the recreational nature of getting out and going for a walk, which there’s nothing wrong with, but it’s not the kind of walking I’m writing about it in this book. What I’m describing is walking to the kinds of daily destinations that fill up our life: a school, a store, a coffee shop, a park, a restaurant, an office, etc.

The second item, however, is something that is all-too-often overlooked. As Mr. Cowper and Mr. Frost described, we crave variety. If I have only one walking route I can take to get to my destinations, walking quickly begins to feel less interesting and more like a chore. If I have a variety of paths I can take, I am much more interested in getting out and going. Depending on the weather, my mood, what I’m aiming to do, or who I might be walking with, I can select a path that fits the moment.

In urban planning terms, we call this variety a network of streets or paths. The network is more than a sum of its individual parts. A simple grid of streets, for example, can exponentially increase my options compared with a street network that provides only a couple of ways around.

Since most of our communities built before the 1940s were places where people walked daily, they are designed in this fashion. Following World War II and the adoption of the car culture, we radically changed our cities and towns so that they suited fast-moving cars. Planners and traffic engineers came together to create a new system of streets, giving them names such as collectors, arterials, and the now-ubiquitous cul-de-sac. Instead of a connected network, the new system was conceived to work like modern sewage systems, where cars were collected from endpoints and distributed to larger and larger pipes as they moved along. This approach fit the technocratic spirit of the era, as we believed rational, industrial mindsets could solve all manner of problems with city life. Cars became easier to count, and highly sophisticated traffic management systems were put in place. Alternate routes were limited on purpose, since traffic had to be contained to where it would cause the least negative impacts. Walking and biking were considered solely as recreational. We created a world based around the mobility the car provided, but in a twist of fate gave ourselves far fewer options for total mobility.

Another bit of simple truth: It’s very difficult for planners to modify our car-oriented places so that they are interesting and useful to walk around. The streets are often so long that they are boring, and the destinations are spread so far and wide that walking is very inconvenient. Because of the design of the arterial-collector system, very few alternate paths exist. And, some of those other paths are not pleasant to walk along because of the traffic. It’s simply a different system, with a different set of transportation priorities. This is not to say it’s impossible to make changes or improvements in this environment, but it’s certainly very difficult.

In our older places, however, the bones of good networks still exist. The cities are built with simple grids of streets, the blocks tend to be shorter, and the destinations are closer together. In my particular case in Savannah, I have a virtually endless number of choices for which way to walk on any given day. That set of options not only adds interest to my errands, but it also allows me to see more of my neighborhood and more of my city as a result. I am never bored.

The funny coincidence of living in a place that is more connected and has a finer network of streets is that it is not only better for walking — it also has benefits for driving. When I choose to drive, my routes are more direct. I don’t have to drive a long way out of my way to go a short distance, which is very common in our newly built areas. And since I have a great number of streets to choose from when driving, I can easily avoid any congestion or emergency by just sliding over to the next street. Some people might call that a win-win.

In any case, there’s no question that having variety and choices takes a simple walking experience and makes it a daily pleasure.

If streets are closed for public events, it doesn’t disrupt my life.

I’m not only a walker, I’m also a runner. I’m not hard-core, mind you. I’ll run a few times a week, and do a 5K, 10K and even a half-marathon occasionally. Some of my real running friends would say that’s pretty light, but I prefer to think that they’re a little bit nuts.

Runners take over in Savannah.

A lot of people get annoyed with how often the streets of their city are closed down because of races or special events. As running has increased in popularity, it’s common in most cities to have an event of some kind almost every weekend when the weather is nice.

Races are hardly the only events that force temporary street closings. Street parties, parades, festivals, open street days, or even visits by dignitaries can all cause significant disruptions to the flow of cars through a city. Commuters hate having to deal with these situations, as there’s nothing worse than being stuck in traffic with no options.

Although I’ve already established the virtues of having a network of paths to take in the previous section, allow me to add one additional benefit of having variety: I don’t care when special events cause disruptions. In fact, it’s even one better than that. As a walker, when streets are closed for events, I actually get to enjoy them. They don’t affect my life in a negative way.

Now that I’m immersed in a culture of walking and biking regularly, when I hear people complain about big public events, I feel sorry for them. I feel bad that they feel so rushed in their days that they can’t stop and enjoy the sights and sounds of people gathering together for fun. I feel sorry that they are more worried about getting to a store across town than about enjoying the moment. It’s these kinds of spontaneous gatherings of people that we revel in when we’re on vacation. And yet, when we return to our daily lives, we too often curse them.

I’ve even heard people say things to the effect of, “There’s going to be a festival every damn weekend before long.” Which makes me stop and wonder — would that really be such a bad thing?

Snow days are great days.

I don’t live in a snowy climate anymore, but one thing I surely miss is snow days. I miss those absolutely wonderful days when the sky dumps enough snow that it disrupts everyone’s life.

Why do I so love snow days? Because in a walkable place, snow days are great days. I can get outside, walk around, and just enjoy the beauty and fun of it. I can still walk to stores if I need to, and I’m not consumed with what conditions the roads are in.

Snow days are meant for kids.

And of course, for kids, a snow day is nothing but fun. Having a nearby park with a hill for sledding is as fun as it gets.

A snow day is also one of those rare moments when you really notice just how much of the noise of life comes from vehicles. When the snow comes, the whole city gets eerily quiet, even in the midst of a major metropolis. Sounds that usually go unnoticed become audible. And the sounds we are more used to hearing (from traffic, trucks and sirens) are mostly absent.

I sure don’t miss the cold weather, but I do miss those wonderful days where the snow makes it all shut down, and life gets a lot simpler.

2nd Interlude — Sashaying to optional places

Of course, not every destination is necessary: many are just for entertainment. Here’s a few such places that I find myself walking to frequently.

Coffee shop.

Another coffee shop.

From the movie LA Story

Sara: Why don’t we walk?

Harris: Walk? Ha ha ha! A walk in LA!