In Paris, with miserable weather, in thousands of outdoor drinking and eating places, the generations gather to talk and stare . . . which is what life is all about. Gathering and staring is one of the great pastimes in the countries of the world.

— Ray Bradbury The Small-Town Plaza: What Life Is All About

No matter how much we strive for individual identity, we can’t escape the fact that humans are social animals. We not only enjoy the social contact with others, we crave it. It’s in our nature, and there’s ample evidence that humans don’t thrive in isolation. In small doses, sure, isolation can be refreshing. But too much of it does strange things to people. We’re hard-wired to seek out other people in all sorts of situations and make connections, whether we’re introverted or extroverted. You might even say the survival of the species depends on it.

Walking is a fun social activity.

What I really enjoy about walking is that it fills that need for sociability, especially if you’re in a place where there are lots of other people out walking. I think that’s precisely why we tend to vacation in places where walking is the norm, because that sort of public socializing is something most Americans lack in their day-to-day lives. We get up, we drive to work, we drive to shopping, we drive to entertainment, and then we drive home. Sure, each of those individual activities may provide some social stimulation, but not the kind of relaxed, informal sociability I’m talking about.

What do I mean? The other day, Jamie and I were out walking, headed downtown to run a couple of errands and just enjoy a Sunday. On our walk downtown, we ran into our trivia buddy Roy walking in the park. At sixty-four, Roy is the social butterfly of Savannah (he still carries with him a desk-size written calendar of all of his activities), and he was checking out a group of young hippies in the park who have a new drum circle. The drum circle — that’s a whole other story.

At any rate, running into Roy turned into a fifteen-minute conversation. We chatted about what was going on in the park, what we’d done over the weekend, and what was coming up during the week. Of course, we also talked a little about some mutual friends. I learned a new thing or two about Roy, and I’m sure he learned something about us as well. And, it was just plain fun — a happy interruption in the day.

The thing is, this type of random run-in happens all the time when you live in a walkable place. We’ve had days or nights out where we’ve bumped into several different friends from entirely different circles, all in just a few hours. And those encounters don’t happen only inside a crowded bar or a noisy coffee shop. They happen outside, on the streets or in the squares, as we’re going about our own fun. One of the primary characteristics of a great walkable place is how living outdoors in public becomes a much more frequent occurrence.

The kind of sociability I’ve described is not just fun (and interesting), but something most of us lack in our daily routine. Despite the romantic call to the wilderness, we humans need regular connection with each other as much as ever. There’s simply no amount of Facebooking or social media that can replace it, no matter how sophisticated our technology becomes.

I have more disposable time.

We think of cars as time-saving devices. If we want to get somewhere fast, the obvious solution is to get in the car and drive there. Cars can take us to faraway destinations relatively quickly if there’s no traffic — as a result, we perceive car use as efficient time management, and even time gained.

What I’ve found is more often the opposite.

I’ve discovered that by walking and biking I spend less time getting to my destinations than when I drive. As a result, I now have more disposable time than I used to have.

I fully understand that what I’m describing won’t be true for everyone, and it won’t be true for every place. But here’s how it works for me.

In my former home in Kansas City, I could walk to a few destinations that I went to regularly, but many others were so spread out that I had very little choice but to drive to most of them. For example, I had a nice selection of restaurants and coffee shops that were an easy walk. A few close friends lived within walking distance, and if the weather was nice, I could walk the twenty-five minutes or so to work. But my many business trips took me to offices around the city, most shopping wasn’t convenient, and I often wanted to explore the food and drink options beyond my neighborhood. I could have taken the bus to some of those places, but the bus service in Kansas City was so bad that in most cases riding the bus took substantially longer than driving.

The situation I have now is quite different and, as I’ve mentioned, was a major factor in why I chose to move here. I have most of my daily and weekly destinations within a fairly easy walk. Ten to fifteen minutes from my front door gets me to many places I need to go, including all manner of food and drink options; local services like groceries, banks, barbers and doctors; as well as parks, recreation and even the very frequent festivals. The act of driving and looking for parking actually takes longer, in part because it’s less direct and in part because parking is sometimes difficult to find. As a result, I spend far less time getting to destinations now, when I travel primarily by foot and by bicycle, than I used to when I drove pretty much everywhere — and much less than the average person spends.

Average commuting times for select cities, each way

(Source: US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2010)

In fact, the average American spends an hour and a half a day behind the wheel of a car. Just think for a moment how much time that is. Adding that up over the course of a year comes to about three weeks of time. The average commute in our country takes twenty-five minutes each way. And that’s the average. In contrast, my average time behind the wheel is about two hours per week.

Of course, I trade some of that driving time for walking or biking time, but the difference is that the latter is time I generally enjoy. As mentioned earlier, walking is healthier, more relaxing, and just generally makes me feel good. Most importantly, I find that by living in this more compact way, I have additional time to do the things I enjoy. During those times when I am stuck in traffic, I find myself giving thanks that it is not part of my daily life.

Only by removing ourselves from the day-to-day grind of driving everywhere — which most Americans simply accept as part of living the good life — do we realize how poor that quality of time actually is. We’ve done our best to make sitting in the car as good as we can, with comfortable seats, premium audio systems and hands-free phone devices. But the reality is that it’s a lousy way to spend ninety minutes a day.

Personally, I prefer to spend my time with friends and family or tinkering on my latest project, rather than behind the wheel. If I devote that extra time to being sociable, it helps strengthen my relationships. Other times, I want to dive into some personal hobby, or even relax and do nothing. Finding time for all of those activities is possible by choosing to drive less and live more.

Less time behind the wheel means more times like these.

I’m routinely reminded of the fact that not everyone is extroverted, as I tend to be. Many people get worn-out with too much human interaction and need to recharge in solitude. Still others are private people and generally limit their socializing. And all of us like being alone at times. Nothing is wrong with any of these personality traits.

But for those times when socializing is something I want to do, I’ve found it’s far easier in a walkable place. When I wanted to meet my neighbors, or now, when I would like to know them better, the design of my neighborhood and its buildings allow that to happen more intuitively than in most suburbs. If I have friends who live within an easy walk, I’m much more inclined to visit them than if I had to drive. A ten-minute walk to say hi is a pleasant experience, whereas a ten-minute drive is long enough to keep me from making the trip.

A lot of people may question what I’m saying. After all, is it really that hard to get to know your neighbors, regardless of the setting? With a little effort, of course, it’s not that hard to get to know people. But the design of a place does impact our behavior in both obvious and less-than-obvious ways.

The placement and details of our streets, buildings and landscapes can help or hinder human interaction. The smallest elements of design often alter our behavior in ways in which we are not aware. In community design, we see this routinely.

My brother is a psychologist, and we once hosted a discussion at his workplace about whether design can really impact the bonds of community. I was faced with a room full of skeptical PhDs, but, as a young architect, held my own in arguing the affirmative. My case boiled down to observed experience, though others have before and since completed detailed peer-reviewed studies. Consider it this way: think for a minute of a neighborhood where the buildings are fairly close to the street, the houses have front porches, and people regularly walk on the sidewalks. Compare that neighborhood to one typical of most of those we’ve built in this country in the last thirty or forty years. The streets are wider, there is probably a sidewalk on only one side of the street, garages dominate the houses, and in the absence of front porches, people generally hang out in their backyards. In which type of place do you think it’s more likely for you to run into people casually, or feel encouraged to go knock on a neighbor’s door?

I’ve lived in both kinds of places and can tell you there’s a tangible difference in the social feel. This does not mean that I know all of my neighbors. But it’s quite obvious that the opportunities to engage are easier and more frequent in my current neighborhood than in the more insular world of suburban-style streets.

Whether we speak or not, I certainly see my neighbors more frequently now than in my previous homes, and they no doubt see me as well. These kinds of public connections are significant because they reinforce good civic behavior, which I even notice in myself on occasion. Knowing that people will observe and register my actions, I am more likely to put trash where it’s supposed to go, pick up the dog poop, clean up my porch, and generally behave more like a grown-up.

I’m not a sociologist, so I can’t explain why these behaviors exist. But many good people have studied the ways in which our places impact our lives and have come to the same conclusions. We humans are subject to influence by a variety of design variables. And yes, some of those include the actual design of our neighborhoods.

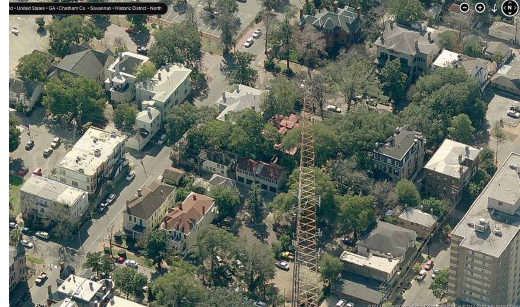

Compare and Contrast: Which place looks more welcoming to you?

Not all of the social benefits of walking will appeal to everyone. We all have different temperaments, interests and tastes.

I love to learn about the history of where I live. I can do that more easily as a walker than when I’m whizzing through the streets at thirty-five to forty-five miles per hour. When walking, the sights and sounds are up close and personal instead of flashes that disappear before I can identify them. I get to experience life at three miles per hour. At that pace, I get to see the details of my neighborhood and city. The signs that note the year of a building’s construction or the monument to someone from a previous century are all legible. I can actually stop, read and learn something about the history of my city. This makes me feel more connected to the place and the people who came before me.

Living history.

In particular, I find that walking allows for chance conversations with people who know a place’s story — talking with them is better than learning from a history book or a description of a monument. Walking around Savannah, I’ve met and talked with people who have lived here for decades and told me wonderful anecdotes about the city. They know what was in a particular building, who did something important in a certain square, and generally what life was like in previous eras. On one fall day last year, I noticed an older man walking slowly around a square as he was leaving church. We said “hello,” and then began to chat in a friendly way. He described for me in great detail some of his experiences as a child growing up in the neighborhood many decades ago and changes in the area, such as the bank that used be on the corner and the drugstore opposite. He described how different life was then, in both good ways and bad.

Such encounters help me understand the city, and they enrich my life. This type of interaction is something I wouldn’t get locked up in my car, rushing to the next strip mall or drive-through.

I learn more about people.

I’m an architect, so at times I tend to focus first on how walking helps me interact with buildings and places before I discuss interaction with people. We all end up fitting some stereotypes!

By far, the most important connections that walking facilitates are those with other humans, as I began discussing above. The vast majority of the time, such interactions are silent. We walk by each other, perhaps smile, and continue on our ways. But, because I walk most everywhere, on a regular basis something else happens. I actually speak with people!

I may learn about the city, as mentioned, or I may learn about the person. What I learn could be something seemingly minor, such as something that is readily apparent about the person. Perhaps it’s that he or she obviously likes bright clothes, or obviously is a people person, or obviously had a bad day. The list is endless, since the behavior of human beings is so endlessly unpredictable.

Or what I learn might not be something obvious. I might interact with someone who is different from me in some significant way. That person might be poorer, wealthier, louder, quieter or just plain out of their head. The reality is, when we walk around in public, we get the chance to see, hear and smell all of humanity. And by that I mean all of humanity: the good, the bad and the bizarre.

I understand that this type of interaction is not for everyone. Many people prefer to surround themselves with others who either look like them, are of the same income group, or the same age. We find no shortage of ways to self-segregate in a free society.

When I drove all the time, I never had these kinds of interactions with people. My chance interactions were through the closed windows of my car or maybe with the windows down, if I got lucky. I’m talking about interactions such as the occasional smile or wave, but frequently it was an angry look or upraised middle finger.

Today, not all of my interactions while walking are shiny and happy ones by any means. But more often than not, something happens that makes me smile or think, instead of making me hit the gas pedal harder.

It’s inevitable that as we move through life, what we want out of a home or a neighborhood changes. As a young adult, I wanted to rent somewhere cool and cheap and didn’t care about much else. Later, I wanted a little more room to call my own. When I added dogs to my life, I really wanted a small yard for them, and for me, frankly. People have kids, get married, get divorced, get older, etc. The point is, we rarely stay in the same house or apartment for more than five or ten years.

The downside to moving so much is that we often feel we have to move to an entirely new neighborhood if we’re staying in the same city in order to accommodate our evolving requirements. So many subdivisions and communities are filled with the identical house or apartment for block after block that when what we want in our living space changes, we have to look farther afield for something different. If we’ve made good friends where we are, moving means leaving them behind to some degree and putting a strain on social bonds that we may enjoy.

In a walkable neighborhood, a change in housing requirements (or desires) manifests itself differently. A well-planned and well-built walkable place has a wide mixture of kinds of houses, condos and apartments. This is part of the nature of more compact neighborhoods. If I like a particular pedestrian-friendly neighborhood, I can probably find something that suits whatever phase of life I’m in.

In my two and a half years in Savannah, I’ve lived in three rented apartments of various sizes and designs within just a few blocks of each other. Should I choose to purchase a home, the same area has townhouses and condos for sale, as well as a wide range of single-family houses. Should I reach my golden years here, there’s even some senior housing in the neighborhood.

Why do I care about staying in a neighborhood? I care because those social bonds that I forge in one place can continue to build over time. I won’t lose friends simply because I get older or married or divorced or have children — because I won’t need to relocate to accommodate different housing requirements. Of course, you can always keep friends no matter where you and they are, and today’s technology makes it easier. But it’s also true that we tend to have the strongest social bonds with the people we see and interact with the most often. Proximity still matters for most relationships.

Something for everyone.

The bottom line is that I have more options in a walkable place. I may want to move away from long-time social contacts, but I don’t have to. I may want to move into a different neighborhood or part of town, but I don’t have to. The choices are mine, not forced upon me.

I won’t be confined to being around only old people as I age.

There’s a strain of housing development unique to the United States called age-restricted. You know these places — Sun City, del Boca Vista Phase 3, the Villages, and so on. These are places for Active Adults, or fifty-five-plus, or able-bodied retirees enjoying their golden years — in other words, retirement communities.

These are developments that have filled a niche. As we’ve become more and more mobile as a society (thanks to our cars), we’ve increasingly formed communities based on the phase of life we’re in. We have an apartment or rental community when we’re young, a starter home community for that first house, and a move-up community for when we need more house and yard. Then, when the kids are gone, we head towards the fifty-five-plus, or age-restricted, places. The market has nimbly responded to how we’ve separated our communities out into so many different pods.

But our communities don’t have to be segregated in this way. We lose something very important socially when people hit a certain age and are practically expected to move to a different part of town or even a different state. In the previous section, I noted how in my neighborhood I have a variety of housing options available, so I don’t have to leave as my needs change. For me, that’s a big deal, because I, for one, don’t like living where I’m surrounded by people who are all just like me, or all the same age as me.

Hopefully, all of us will get to experience old age. I know that if I reach my senior years, the last thing I will want is to be surrounded by only other old people. I can’t imagine anything more depressing and confining. Golf course communities and early-bird specials? No thanks.

This age diversity isn’t just something that will be important to me later on — it matters to me now, in my forties. The daily sights and sounds of people younger than me enhance my life immeasurably. Seeing young kids, college students and young professionals keeps my mind more engaged and active. How boring would it be if I only got to see and hang out with people my own age all the time?

I never have to worry about drinking and driving.

Let’s face it — we humans like to imbibe. Wine, beer, whiskey and other liquors fill our homes, our restaurants, our bars, our festivals, our holidays, etc. There’s nothing wrong with that — it’s part of our lives, and I’m not alone in enjoying a few drinks. I’m a big fan of craft beers, good wine and classic cocktails, either with a meal or without.

Life is too short to drink cheap beer.

But there is a problem unique to American cities and towns related to alcohol, and it’s directly connected to our acceptance of driving to almost all of our destinations. That problem is our proclivity to get behind the wheel of a car and drive after drinking. It’s a dangerous and foolish thing to do, and I’m not too proud to admit I’ve done it myself. For most of my life, I’ve lived in cities where driving was the only realistic way to get around, and I’ve succumbed to the stupid impulse to drive myself home when I shouldn’t have. Luckily for me and everyone else, none of the worst-case scenarios have happened. But I repeat: I’ve been lucky.

Alcohol and drug abuse are complex, touchy subjects, as is drinking and driving. People are seriously injured or killed by drunk drivers all too often. It’s such a pervasive problem in American society that we are barraged with advertising messages warning us against it. And there are constantly evolving strategies and tactics designed to reduce the incidence of drunk driving, including tougher and tougher DUI laws, frequent sobriety checkpoints and more readily available “Tipsy Taxis” at special events.

The problem is that no amount of MADD commercials or creative strategies will eradicate people’s desire to drink — and they certainly won’t overcome our spread-out cities. In my experience, only one approach can solve the problem, and that’s living in a place where you don’t have to drive.

In my living situation, I can drink as much as I like and not have to worry about consequences — except to my own liver and the potential for embarrassment. Living in a pedestrian-friendly place means I can walk home after having some drinks or take a cheap taxi, as I’m close enough to make the fare home inexpensive. I’m never a threat to anyone else or to myself.

I find this aspect of living in a walkable place to be a great emotional relief. “Who will be the designated driver?” is a question that never has to come up, nor does the accompanying awkwardness and lack of fun. I get to relax and enjoy myself instead of running a blood-alcohol-content (BAC) calculation in my head while I’m out. Even better, I don’t have to play nanny to anyone else I’m with to monitor his or her BAC. I also don’t have to crash uncomfortably on a friend’s couch because I’ve had too much to drink.

Think about that feeling you have when you’re on vacation somewhere very relaxing and walkable. You find yourself often strolling over to a bar or restaurant to have a few drinks. Afterwards, you likely stumble back to your room and sleep the night away. We all do this time and again, then get home and marvel at how relaxing the vacation was. All the while, it never crosses our mind that one major reason it was so relaxing was because driving was not an issue. At home, we meet friends for a happy hour but cut the fun short because we have to drive. How much more relaxing is that glass of wine, knowing we don’t have to get in a car and drive home? And how much safer is it for everyone? Why do we settle for that carefree attitude only on vacation?

Lawn care is not my thing. I know: it’s heresy for an American man to admit this. But it’s true. The last thing I want to spend my time doing is endless hours of yard work. It’s pure drudgery for me, and when I do it, all I can think about is what else I’d rather be doing.

There are too many people like me who don’t like lawn care but have chosen to live in a way that makes it a required chore. We tend to have big yards that need care because we think we have to have them. We dedicate weekend and leisure time to something we, at best, tolerate. At every opportunity, we look for someone else to pick up the slack. Can the kids mow the lawn? The neighbor kid? Parents? A landscape company?

I know there are a sick and twisted few who love lawn care. They live for the riding lawn mower, the edger, the seeding and weeding, and the hours of worry about whether the grass is getting enough water. Count me out.

My lack of desire to have or maintain a yard doesn’t mean I don’t want and need beautiful and usable landscapes in my life. To the contrary, I think as humans we all crave some form of regular time in nature, and we love getting our hands dirty every once in a while.

So how do I reconcile these competing urges with my lifestyle choice?

First, even though I don’t like lawns, I do like gardens. Whether it’s growing some simple flowering bushes, or having my own vegetables, I do find it rewarding to put whatever small slice of land I have to productive use. It not only can add beauty, but also can provide me with something useful: fresh food. This year, in a very small piece of sandy earth, I’ll be growing some tomatoes, onions, cilantro and jalapeno peppers. I won’t win any farm-to-table awards, but I will have some cheap, tasty food to eat this summer.

Second, when I need a bigger hit of “green,” I have parks nearby. Whether they are small squares or large city parks, I have access to expanses of trees, flowers and lawns within an easy walk. These places do so much more for me than any toil in the backyard ever could. Not only are they big enough to spread out in and enjoy in a wide variety of ways, but I don’t have to take care of them myself.

My backyard.

Not all neighborhoods have as much quality public space as what I have available to me in Savannah. I’m lucky in that sense. But it’s not an accident that I live here — the public spaces were one important reason why I chose to live in this particular city. Unfortunately, many of our cities (of all sizes) are in desperate need of better located and better designed parks and squares. Having this green space nearby and easily accessible makes the big backyard something I never miss.

My trash is better looking than your trash.

I’m a guy. So, apparently trash is my lifelong responsibility.

I can’t stand the weekly mess that appears in the streets of so many places. It’s a bit of my own personal OCD. We put the trash out in front of the house for everyone to see. If we’re lucky, the trash haulers actually get all of it into the truck, rather than leaving portions of it scattered on the ground. In my experience, getting that lucky is a rarity. Instead, in most of the places I’ve lived, my neighbors and I frequently battled trash of all kinds strewn around the fronts of our homes. Having debris littering the ground is not just a pain, it’s also a blight.

In the best walkable places, the residences have alleys in back where the trash receptacles are kept. Alleys (or “lanes,” as they are called here, and elsewhere in the South) are a much better and more attractive way to deal with trash and recycling; the bins and containers are out of sight and don’t clutter up the street. I’m far less likely to be concerned about the appearance of the back of my property than the front, since very few people actually see the back. And likewise, I’m not as concerned with what I see of my neighbors out the back, as opposed to what can be seen out the front door.

Where should the trash go?

This distinction between front and back, or public and private, is part of what has changed over the years in terms of how we build our cities. We used to have buildings with a clear front that was public and a clear back that was private and quiet. People mostly walked to get where they were going, so the relationship between the front door (and front porch, if there was one) and the street was very important. Think for a moment of the scene from It’s a Wonderful Life when George Bailey walks by Mary’s house, and she has a conversation with him from her window. It’s a small but fantastic illustration of how much more public our lives were when we used to walk routinely. And since our lives were much more on display, that distinction between public and private was extremely significant. Everything from the front door of the house through the back was designed with public versus private in mind. The more public the front became, the more private the back needed to be, to give us a way to balance our human needs for both private time and sociability.

As we adopted the car culture, we shifted this arrangement of front and back, public and private. The front of our homes became like the alleys of old — the front is something we essentially drive into, entering our garages with our cars. The back has become our semi-private space, with big lawns and usually fences between yards. Instead of socializing in the front and having private gatherings in the back, we shifted to socializing on the back patio, deck or yard and having private gatherings inside the house.

This front-back relationship has impacted every aspect of our lives, including the topic of this section: trash. In previous eras, the notion that people would display all of their garbage in front of their houses would have been inconceivable — it would have been considered unseemly. Trash obviously belonged in the back, in a more private, hidden spot. As with trash, the trucks themselves were largely unseen, being relegated to the alleys rather than cluttering up our streets.

In most places, that’s all changed. We now put our colored bins, our recycling, our bags of leaves, our old furniture and so much more out front for the world to see. It’s an element of ugliness that we’ve come to accept as normal. But in some walkable places, we still have alleys that can handle garbage and recycling trucks, which leaves our fronts a little more well-kept. For me, getting the trash out of sight has a positive impact on my quality of life. For society at large, the changing nature of where we put our trash is a classic example of how changing to accommodate cars has affected so many details of our daily lives.

My parents infected me with the travel bug at a young age. There’s nothing I enjoy more than getting to a place I have never visited and going out to explore. On foot, of course.

The funny thing about vacationing is that we typically spend our hard-earned dollars going to places where we get around primarily on foot. Fifty weeks out of the year we work hard, scrimp and save, and spend hours sitting in traffic so we can spend two weeks somewhere in Europe or Mexico or New York or Disneyworld where we can . . . walk.

When on vacation we walk, we live a bit slower, and we find ourselves enjoying the day just a little more. Sure, some of that is because we don’t have the pressures of the daily grind. But how much of our enjoyment is because we have a completely different kind of experience getting around? Instead of sitting in a car and traffic, we use our own bodies to explore the world around us. My sense is that quite a bit of our happiness on vacation stems from being on foot.

So why don’t we just choose to live in places where we can do this all the time?

But I digress.

I’m famous in my family for taking everyone on extended walks when we’re together on vacation. “It’s just up around the corner” in my language means it’s several more blocks. “We’re almost there” means we’ve got about another ten minutes to go. My family thinks I have a different meter for distance and walking than what normal people do.

When on vacation, I can jump right into walking and spending the days out and about because of how I live my life when I’m home. Because I’m used to walking on a daily basis, it’s no big deal for me to walk long distances when I’m on vacation. And, as with being at home, walking while on vacation means I get to see so much of a place up close and personally.

Walking adds to my pleasure on vacations and allows me to get to know an unfamiliar place much more quickly. If you’re not used to walking and have to limit yourself while on vacation, your experience and interaction with that place and its people becomes far different and, in my opinion, less rich.

Walking regularly is one of those activities that is truly self-reinforcing. The more of it I do, the more I like to do. The less I do — which may happen if I’m on a work trip and in a location that isn’t conducive to walking — the harder it becomes to motivate myself to walk at all.

So take that long walk on vacation. Enjoy the sights and sounds at a slow pace. Imagine doing the same in your own town. Then do it, and you’ll no doubt find yourself walking longer distances in no time. Better yet, you’ll develop a greater appreciation for your own surroundings.

4th Interlude — Far beyond a simple stroll

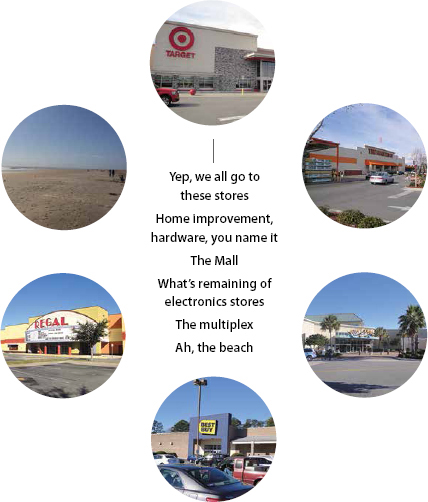

Some places are either too far to walk, or too unpleasant of a walk to draw me there on foot. But, they still require a trip occasionally. Here’s a few.

And they’re trying to get through

There’s no single explanation

There’s no central destination

But this long line of cars

Is trying to get through

And this long line of cars

Is all because of you

You don’t wonder where we’re going

Or remember where we’ve been

We’ve got to keep this traffic

Flowing and accept a little spin

So this long line of cars

will never have an end

And this long line of cars

Keeps coming around the bend

From the streets of Sacramento

To the freeways of L.A.

We’ve got to keep this fire burning

and accept a little gray

So this long line of cars

Is trying to break free

And this long line of cars

Is all because of me

— Cake lyrics, “Long Line of Cars”