10

The establishment of Roman control

The military history of Britain in the first century AD has received considerable attention from archaeologists and historians and need not be enlarged upon here, but it is necessary, for the sake of our theme, to examine the reaction of the native tribes of Britain to the threat and actuality of Roman rule.

In the early decades of the first century AD the presence of Rome just across the Channel was a political reality to which the British tribes had to relate. The Trinovantes/Catuvellauni seem to have been on friendly terms with Rome, and the quantity of trade goods and diplomatic gifts which poured into their territory is a measure of this relationship. Using the same yardstick it could be argued that the other coastal tribes – the Cantii, Atrebates and Durotriges – were far less favoured and may even have been hostile. Such a situation would not be at all surprising: the Cantii had opposed and attacked Caesar, the Atrebatic household was founded by Commius – a sworn enemy of Rome – while the Durotriges may have been punished and thereby impoverished for supporting the Armoricans in their revolt against Rome in 56 BC. But attitudes and allegiances established in the wake of the Gallic Wars are likely to have changed in the ninety years or so leading up to the conquest, especially if the growing strength of the Trinovantes/ Catuvellauni was seen as a threat by neighbouring tribes and perhaps also by the Roman authorities. Pressures of this kind would have created new hegemonies and new rivalries, while the immediacy of the Roman invasion threat might have encouraged the more opportunist leaders to alter their allegiances in the interests of expediency. Certainly the flight of the Atrebatic king, Verica, to Rome just before the invasion might suggest that the tribe was beginning to look to Rome as a patron in time of stress.

Tension was further heightened by the accession of the two Trinovantian or Catuvellaunian leaders Togodumnus and Caratacus in or very soon after AD 40, following the death of Cuno- belin. The instability which must have been created by a change of leadership after so many years of unified rule may well have led to internal divisions within the tribe, in addition to a feeling of unease in the surrounding areas. In about 42 Verica fled to Rome to ask for the help of the Emperor Claudius. No doubt Verica would have provided the emperor and his advisers with an up-to-date assessment of the political situation in Britain. Moreover, his flight could have been interpreted by the Roman propaganda machine as the expulsion of a friend and ally in whose interests military intervention in Britain was the only honourable course.

The invasion began towards the end of April AD 43. The exact geography of the first weeks is unclear. While it has traditionally been believed that the invasion force made a concentrated landing in Kent, in the vicinity of Richborough, it has plausibly been argued that the main landing took place on the Solent coast near Chichester (Manley 2002). In any event, the Romans’ aim was to reach the Thames. After several unsuccessful skirmishes somewhere in the south-east, the British resistance army led by Caratacus and Togodumnus withdrew beyond a river and there pitted their whole weight against the Romans. For two days the river line was held, but Roman superiority of arms eventually triumphed. The battle was decisive. British opposition melted away; Togodumnus subsequently died in battle while Caratacus moved to the west to continue the fight, eventually ending up as a resistance leader in south Wales among the Silures. The dramatic collapse of centralized opposition in the south-east was rapidly followed up by the Roman advance across the Thames and the drive on the native capital at Camulo- dunum, led by the emperor himself. By the end of July the opposition of the south-eastern tribes had been totally smashed and all that remained was to mop up pockets of resistance and establish military control.

The relative ease of the initial stages of the advance had depended to a large extent upon a stable left flank, a stability which was provided by the buffering effect of the Atrebatic enclave in Sussex and east Hampshire. Had it not been for the presence of this friendly tribe, the hostile elements of the south-west could have created a serious threat to the extended Roman supply lines from the coastal supply bases. It was, then, very much in the Roman interest to ensure the political stability of the area. The flight of Verica to Rome implies unrest, but whether as the result of external threats or of internal differences is unknown. The Roman attitude was clear enough, for almost immediately there appears in the area a client king, Tiberius Claudius Togidubnus, who was later to style himself ‘great king in Britain’ (Bogaers 1979). Togidubnus has in the past been called Cogidubnus but here we have accepted the new reading proposed by Roger Tomlin (1997). While it is possible that he was left by Verica to hold on to the reins of government in his absence and was therefore already in power when the Romans landed, it could be argued either that he was a Roman nominee selected at the time of the invasion from among the ruling household or, more likely, that he was a member of the Atrebatic aristocracy living in exile who was brought in by the army. An explanation in these terms would account for the rapid and dramatic Romanization of the kingdom in the thirty years following the invasion. Whether or not the main landing was in Kent, there is a good case for suggesting the landing of a military detachment in the Chichester region to stabilize the area and keep an eye on dissident elements. Such a force could have brought the king with it and established his right to rule by its very presence. A strongly pro-Roman client king could have been used as a diplomatic tool to persuade neighbouring rulers, uncertain of their allegiance, to support the Roman cause. Indeed it may have been through the good offices of Togidubnus that a king of the Dobunni capitulated while the Roman army was still fighting its way across the south-east.

Togidubnus was a success as a client king, for Tacitus records his faithful support of Rome into the 70s or 80s. Two inscriptions from Chichester serve to emphasize the extent of Roman- ization. One records the erection of a statue, probably equestrian, to Nero in AD 58, while the second, a dedicatory slab from a temple to Neptune and Minerva erected to the honour of the Divine House of the Emperor, probably in the early 80s, gives Togidubnus the title of great king, which he may have been granted as a supporter of Vespasian following the upheavals of AD 69. It has also been suggested that the great palatial building at Fishbourne, Sussex, may have been the residence of the king in his later years (Cunliffe 1971b). In total, the evidence for rapid and thorough Romanization is impressive, but that Togidubnus may at first have had difficulty with his subjects is hinted at by the growing evidence of military remains at Chichester, the possibility being that the king may have required a supporting garrison to establish and maintain his control at least in the early years of his reign. Nevertheless, from the Roman point of view the arrangement was a resounding success, as Tacitus puts it (Agricola, xiv), ‘an example of the long-established Roman custom of employing even kings to make others slaves’.

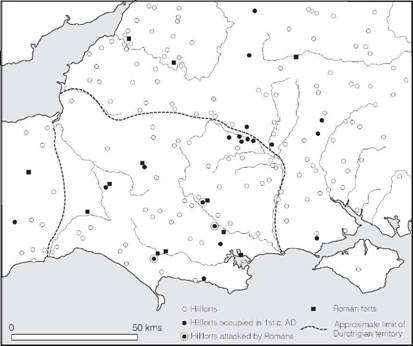

The Durotriges offered a more intractable problem. They remained culturally isolated from the tribes of the south-east, and in place of unified government it may well be that the tribe was split into smaller units owing allegiance to local chieftains. At any event it fell to Vespasian, leading the Legio II Augusta, to hack his way, one hillfort at a time, across Durotrigan territory late in 43 or early in 44. After taking the Isle of Wight, fighting thirty battles and destroying more than twenty hillforts, he could claim to have conquered two powerful tribes. Archaeological traces of the campaign are vivid (Figure 10.1). At the time, native forts like Hod Hill, Maiden Castle and South Cadbury were being actively strengthened in archaic defensive styles, and it is probable that many of the other Dorset sites were being brought into defensive order to meet the threat. Actual attack can be demonstrated at several forts. At Hod Hill the chieftain’s hut was softened up by ballista fire from a tower sited close to the defences, as is shown by the concentration and distribution of iron ballista bolts around the hut. How the inhabitants responded is unknown, but shortly afterwards the fort was cleared and a Roman garrison housed in one corner. Maiden Castle succumbed to a violent attack in which a number of its defenders were cut down in close fighting or killed by ballista fire, their bodies later to be buried hurriedly, but in native style, in a cemetery at the east entrance (but see p. 229). At Spettisbury, on the other hand, a number of bodies together with fragments of their equipment were bundled unceremoniously in a large pit, possibly at the hands of the Roman army tidying up after an attack. As more of the Dorset hillforts are excavated similar evidence will no doubt come to light, although all were not necessarily assaulted at this time. Tiresome though this method of warfare must have been to the Romans, it posed little real difficulty, for the hillforts of the southwest were designed to withstand local raids rather than Roman siege methods. Nevertheless, the strength of the resistance demanded the garrisoning of a number of separate contingents at strategic points throughout the territory, simply to remind the Durotriges of the military presence.

The reference in Suetonius’ account of the conquest of two tribes in the south-west raises questions to which there are at present no clear answers. It is generally assumed that the second tribe was the Dumnonii but the early military dispositions hardly support this. On balance, it would seem more reasonable to suppose that the area referred to was Salisbury Plain north of the Nadder and west of the Test, which had originally been under Atrebatic domination, but may, by the time of the Conquest, have split with the pro-Roman rulers and become allied with one of the anti-Roman tribes – either the Dobunni or the Durotriges. It may even have been under some form of Catuvellaunian control. At any event, many of the hillforts of the region appear to have been maintained in defensive order, although firm archaeological evidence of attack is at present wanting. That the region was regarded as administratively, and presumably culturally, separate from the surrounding tribes is shown in its classification by the Roman authorities as part of the administrative region of the Belgae.

The political situation among the Dobunni at the time of the invasion is difficult to ascertain but Dio records that a king of the Dobunni offered his submission to Rome. This could imply that the entire tribe went over to the Roman side but it need only have been a faction. Culturally the tribal area was divided into two separate entities, roughly by the Bristol Avon (pp. 189–90), and in the Roman administrative reorganization of the province the southern territory was incorporated into an artificial creation, civitas Belgarum. One possible explanation for these facts is that the northern core of the Dobunni, based on Bagendon, threw in their lot with Rome, perhaps as a reaction to the Catuvellaunian dominance which they appear to have suffered, while the loosely attached southern group went their own way, opposing Rome and paying the price for their opposition by losing their identity. Both regions were, however, garrisoned as part of the military frontier zone, anchored to the line of the Fosse Way running parallel to the Severn–Trent axis.

Figure 10.1 Native and Roman forts among the Durotriges (source: Ordnance Survey, Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age, with additions).

The northern neighbours of the Trinovantes, the Iceni of East Anglia, submitted to Rome immediately after the initial stage of the invasion, their leader being among the eleven kings who offered their support to Claudius. The identity of the king is unknown but it may well have been Prasutagus who remained faithful to Rome until his death. As a Roman client king he continued to issue silver coins bearing a Roman bust and the legend SUBRI PRASTO on the obverse and a horse with the words ESICO FECIT on the reverse. The client kingdom came to a dramatic end with the king’s death in AD 60, and the revolt, consequent upon it, led by his wife Boudica.

The political attitudes of the two remaining tribes in the Midlands, the Corieltauvi and the Cornovii, are not recorded, but the apparent ease with which the Roman frontier was constructed across the land belonging to the former and close to the territory of the latter would suggest some kind of treaty relationship. Quite possibly the Corieltauvi, along with the Iceni and Dobunni, were suffering from the expansionist policies of their south-eastern neighbours and regarded the Romans as the lesser of the two evils.

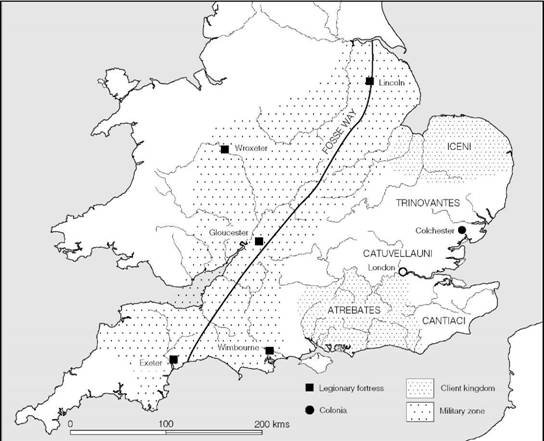

Thus by AD 47 the most civilized part of Britain – the area south and east of the Fosse frontier – had been thoroughly subdued by the army and, apart from the client kingdoms of the Iceni and the Regni (as the southern Atrebates were called), the region was now under direct military control (Figure 10.2). The positioning of the first frontier zone along the Jurassic Ridge is interesting. In adopting this line the Roman strategists were choosing a natural axis of communication fronted by an almost continuous river line – the Severn–Trent axis – but they were also using the three peripheral tribes, the Durotriges, Dobunni and Corieltauvi as their military zone, leaving the south-eastern core tribes and the friendly Iceni to develop into the province while excluding the underdeveloped tribes of the west and north. The use of the peripheral zone as a frontier shows a keen understanding of the political geography of the country.

Figure 10.2 Southern Britain in the decades following the invasion of AD 43 (source: Cunliffe 1988a).

To the west and north of the Fosse frontier were less congenial regions, difficult to conquer and of uncertain productive capacity. These evidently lay beyond Roman territorial desires, but those tribes immediately adjacent to the frontier had to be brought into some form of relationship with the new government. The Dumnonii in the south-west peninsula were probably quite friendly: they had, after all, been trading freely with foreigners for centuries. Moreover, the frontier and the military presence at Exeter successfully isolated the peninsula and rendered the tribe of little potential danger. In the Midlands were the Dobunni, part of whose territory lay inside the military zone and who were therefore forced to behave, and the Cornovii, with whom a treaty had probably been negotiated. Finally, across the north of Britain from sea to sea’ lay a complex of tribes dominated by the Brigantes, whose loyalty to Rome was at most times evident but precarious. Thus the Dobunni and Cornovii were employed as buffer states against Wales, while the Brigantes served to absorb pressures from the northern tribes.

Native resistance had been virtually wiped out in the south-east but, with the powerful war- leader Caratacus, the focus of the anti-Roman movement moved to south Wales, to the territory of the Silures whence, in the winter of 47–8, he launched a fierce attack against a tribe allied to Rome – presumably the Dobunni in the Severn valley. This event, and the growing strength of the British resistance which it represented, forced the new Roman governor Ostorius Scapula to adopt a more aggressive military policy which entailed occupying the west Midlands and thus isolating the tribes of Wales from the Brigantes. To gain the necessary mastery of the Bristol Channel, Dumnonia had to be occupied as well. The preparations did not go unnoticed by the free Britons: the advance into the territory of the Deceagli in north Wales was greeted by a minor uprising among the Brigantes or one of their clients, some of whom may have considered their independence further threatened by this move, while the disarming of the south-eastern tribes, a necessary precaution to protect the Roman rear, was met by a revolt in Icenian territory which had to be put down by an auxiliary detachment.

After these preparations had been consolidated and the consequent unrest dealt with, the army moved against Caratacus, first in Silurian territory and then into the Ordovician lands of north Wales where Caratacus had now moved, presumably to be closer to his escape route to the north. After a while Caratacus finally abandoned his guerrilla tactic and chose to make a stand at a strongly fortified hill-top. The battle was lost and he was forced to flee to the Brigantes, whose Queen Cartimandua handed him over to the Roman authorities in AD 51. The capture of the war leader did not, however, mean the end of Welsh resistance, which was to last for nearly thirty years more. In 51 or 52 the Silures defeated a legion, inflicting very considerable casualties, but during the later 50s they were gradually worn down by the continuous campaigning of Didius Gallus and kept under some form of control by the establishment of forts. But at this time the Roman intention was not to conquer: it was merely to destroy resistance and thus remove the threat to the frontier.

Imperial policy changed dramatically in AD 58 with the arrival of Q. Veranius, whose orders were evidently to conquer the rest of Britain. A single season’s campaigning among the Silures was sufficient to smash their resistance once and for all. When the next season’s campaign began in 59 (under the command of Suetonius Paullinus) the army was able to concentrate on the north, presumably weakening the resistance of the Ordovices before marching against the Druid stronghold on Anglesey, described by Tacitus as a ‘source of strength to the rebels’ (Agricola, xiv) – a reference, no doubt, to the widespread respect and power which the Druids still held as well as to the island’s function as a haven for refugees. Tacitus’ description of the storming of the island is vivid: ‘The enemy lined the shore in a dense armed mass. Among them were black-robed women with dishevelled hair like Furies, brandishing torches. Nearby stood the Druids raising their hands to heaven and screaming dreadful curses.’ Overcoming their fear, the Roman soldiers pushed on to victory and destroyed ‘the groves devoted to Mona’s barbarous superstitions’ (Annals xiv, 30).

The annexing of Anglesey meant the end to organized resistance in Wales, but before consolidation could be undertaken, the Boudican rebellion broke out, requiring the full attention of the army in the south-east. Fourteen years passed before the Welsh problem was faced again, by which time old wounds had healed and a new generation of fighters had emerged. From 74 to 77 Julius Frontinus campaigned to and fro across the principality, suffering some serious setbacks, but by the end of his term of office most of the area had been subdued and it only remained for the next governor, Julius Agricola, to complete the work in a single campaign in AD 78. Thereafter the Ordovices and Silures were kept in the firm grip of a complex of permanent forts and roads. Other tribes like the Demetae of the south-west, who are never recorded as having opposed Rome, were left to develop in peaceful isolation.

While the Welsh tribes on the western border of the province were gradually being beaten into submission, trouble broke out among the northern confederacy of the Brigantes. The first hint of unrest (discordiae) occurred in 47–8 as a result of the Roman thrust into Flintshire. It was serious enough to compel the Roman general to return, but ‘after a few who began the hostilities had been slain and the rest pardoned, the Brigantes settled down quietly’ (Tacitus, Annals xii, 32). The use of the word ‘discord’ to describe the uprising tends to suggest internal troubles, which were probably put down by the ruling house without the need for Roman help. It was probably a minor incident but it heralded the split between the pro-Roman and anti-Roman factions which was eventually to destroy the confederacy.

Caratacus must have been relying on the strength of the anti-Roman feeling when in 51 he fled into Brigantia ‘seeking the protection of Queen Cartimandua’, but he had misjudged the situation and was immediately turned over to the Roman authorities. Such an act is best seen as an attempt by the queen to demonstrate a loyalty to Rome and to underline her own position of power in the eyes of the army of occupation. She had, after all, just witnessed the overwhelming successes of the Roman forces in Wales; some token of loyalty may have been deemed necessary to prevent Roman intervention in her kingdom.

Within the next seven years, however, the unified rule of the confederacy began to split up. A quarrel broke out between Cartimandua and her husband Venutius, both of whom had previously been loyal to Rome. Civil war followed, Venutius immediately assuming an anti-Roman position and, by doing so, taking upon himself the mantle of resistance leader of the free Britons. Cartimandua, ‘by cunning stratagems, captured the brothers and kinsfolk of Venutius’ (Tacitus, Annals xii, 40), which understandably annoyed him and led him to invade her part of the kingdom. The position became so serious that it was eventually necessary for a Roman legion to be sent some time about 57–8, with the purpose of keeping the two sides apart.

Matters finally came to a head during the confusion of the year 69.

Inspired by the differences between the Roman forces, and by the many rumours of civil war that reached them, the Britons plucked up courage under the leadership of Venutius who, in addition to his natural spirit and hatred of the Roman name, was fired by personal resentment towards Queen Cartimandua.

(Tacitus, Hist. iii, 45)

One of the reasons for Venutius’ evident distaste for his wife was that she had married his armour-bearer Vellocatus. ‘So Venutius, calling in aid from outside, and at the same time assisted by a revolt among the Brigantes themselves, put Cartimandua into an extremely dangerous position.’ Cartimandua was forced to ask the Roman administration for military assistance but even the intervention of a substantial contingent of cavalry and infantry could do little more than snatch the queen from danger. Thus by c. 70 ‘the throne was left to Venutius, the war to us’.

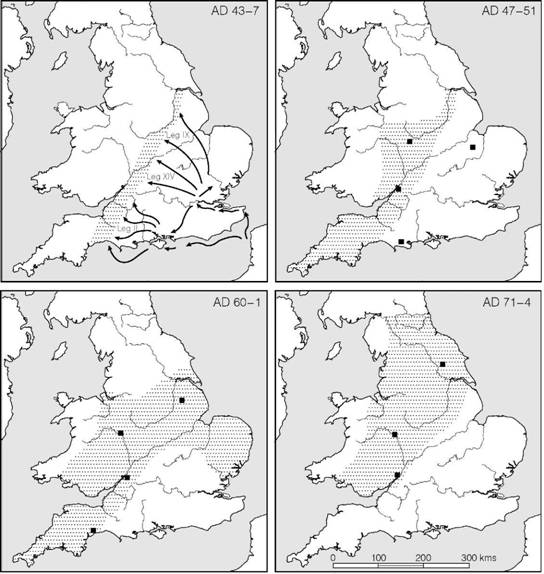

The narrative of Tacitus leaves very little doubt that the north was now in a state of widespread open rebellion led by the Brigantes, backed up by tribes extending far north into the interior. For the Roman province to the south the situation was serious. Immediately Vespasian had gained the throne and the civil disturbances were at an end, the new governor of Britain, Petillius Cerialis, began a three-year campaign in the north from 71–4 (Figure 10.3). ‘After a series of battles, some not uncostly, Cerialis had operated, if not actually triumphed, over the major part of the [Brigantian] territory’ (Tacitus, Agricola, xvii). During this time Brigantian resistance must have been smashed and Venutius defeated, for in spite of a lull of five years or so while Wales was being subdued, there was little further trouble in the area when Agricola began his thrust to the far north. By the early 80s the whole of Brigantia was enmeshed in a close-knit network of forts and roads, which divided the old confederacy into a multiplicity of easily patrolled fragments.

Figure 10.3 The Roman conquest of southern Britain. The military zone is stippled; black squares indicate legionary bases (sources: various).

In the three decades during which the Roman armies were forced to subdue the warlike peoples of Wales and the Pennines, the Romanization of the south-east was being completed, but in spite of a deliberate and well-used programme employing client kings, making substantial monetary loans to noble families, founding coloniae and undertaking elaborate schemes of urban building, progress was by no means smooth. The first hints that all was not well occurred in AD 47, when some of the Icenian tribesmen, objecting to being disarmed, organized a resistance movement and constructed fortifications. The revolt was easily put down but it must have shown the authorities that a certain instability existed in the client kingdom of the Iceni.

Trouble came to a head in 59–60 with the death of Prasutagus. In his will he had adopted the wise procedure of making the emperor joint heir with his two daughters, but it is evident from what followed that the Roman administration intended to absorb the client kingdom into the province, quite probably because it was regarded as a point of instability. The Icenian nobles, led by Boudica, resisted, with the result that a military detachment was sent in;

the first outrage was the flogging of his wife Boudica and the rape of his daughters: then the Icenian nobles were deprived of their ancestral estates… these outrages, and the fear of worse now that they had been reduced to the status of a province, moved the Iceni to arms.

(Tacitus, Annals xiv, 32)

The time was ripe for rebellion, for a new generation of fighters had grown up, the Roman army was heavily occupied in Anglesey and there was a widespread dissatisfaction with Roman fiscal measures.

The Iceni were not alone: their neighbours to the south, the Trinovantes, joined in together with ‘other tribes who were unsubdued by slavery’ (ibid., 32), implying help from beyond the Fosse frontier, perhaps from the Brigantes. The Trinovantes had a particular reason for dissatisfaction, for it was at the site of their tribal capital, Camulodunum, that the Romans had established a colonia which had entailed the appropriation of thousands of hectares of the surrounding farmland for the veterans now settled there. To make the situation even worse, the government had built a temple to the emperor Claudius in the colonia – no doubt in an attempt to refocus the religious feeling of the natives on the empire and away from Druidic nationalism. The policy misfired.

The revolt which followed was violent: London, Camulodunum and Verulamium were destroyed, the Ninth Legion was driven back and the procurator fled to Gaul.

The Britons had no thought of taking prisoners or selling them as slaves, nor for any of the usual commerce of war, but only of slaughter, the gibbet, fire and the cross. They knew they would have to pay the penalty: meantime they hurried on to extract vengeance in advance.

(ibid., 33)

It is evident that in the initial stages, the rebellion succeeded more by its fury than by its planning. Gradually, as the impetus was dissipated, the power of the rebels waned and eventually Boudica was forced to accept a set battle at a site chosen by the Roman commander, Suetonius Paullinus, probably because winter was approaching and food supplies were running short. British fighting tactics had changed little since the invasions of Caesar: cavalry and infantry were mixed up, chariots were still used, and women and children came along as spectators to watch the fight. It was a classic contest with British enthusiasm pitted against Roman order. Inevitably British resistance broke:

The Romans did not spare the women, and the bodies of the baggage-animals, pierced with spears, were added to the piles of corpses. It was a glorious victory equal to those of the good old days: some estimate as many as 80,000 British dead .. . Boudica ended her life with poison.

(ibid., 37)

The situation among the Durotriges seems to have been tense throughout the revolt and indeed the military commander thought it expedient to remain there rather than join the army of Paulli- nus as he was commanded. Some hint of the trouble comes from the hillfort of South Cadbury, Somerset, where a war cemetery quite possibly dating to the Boudican period has been found. This raises the possibility that the famous Maiden Castle war cemetery may also be of this date rather than belonging to the initial advance in AD 43 but the dating evidence is too imprecise to be sure.

The situation did not ease with the British defeat. ‘The territory of all tribes that had been hostile or neutral was laid waste with fire and sword. But famine was the worst of the hardships, for they had omitted to sow crops.’ The events of 60–1 must have reduced eastern England to a virtual desert, and not until Paullinus was replaced could the process of reconstruction begin. Indeed, it was to take ten years before the province was stable enough for there to be renewed military activity in the north.

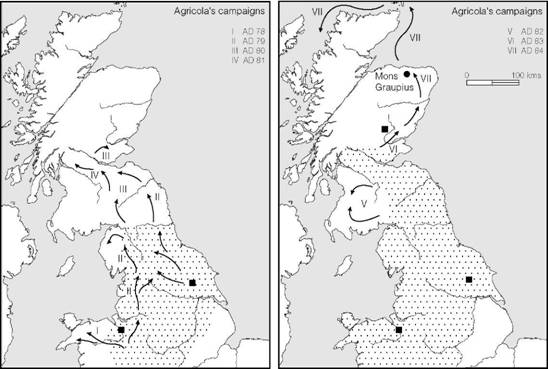

As we have seen, much of Brigantia had been explored by Cerialis in 71–4 and some part of the area must have been thoroughly garrisoned, sufficient at least to prevent further trouble from recalcitrant tribesmen. With the arrival of the new governor, Julius Agricola, in the summer of AD 78, a new forward policy was initiated. After tidying up the occupation of north Wales, Agricola could concentrate on the conquest of the north (Figure 10.4). He spent the campaigning season of 79 consolidating the somewhat tentative occupation of Brigantia, probably as far north as the Tyne–Solway line. By a series of minor plundering raids followed up by bribes, he was able to take control of the entire region, including some tribes which had previously been outside the Roman sphere of interest. The ease with which Brigantia was thus absorbed is a clear reflection of the success of the Cerialian campaigns and presumably of the spread of the enervating luxuries of Romanization from the south. The spirit of resistance and the unity of the area had been smashed.

To the north of the Brigantes lay three tribes: the Novantae of the south-west lowlands, the Selgovae in the centre and the Votadini occupying the east coast. Since it was probably from these tribes that Venutius had received help ten years earlier, they were clearly regarded as a potential threat to the security of the Roman province and had to be brought under Roman control. Accordingly, in 80 Agricola marched north, forcing his way to the river Tay. After wintering in Scotland, he spent the next year building forts and roads with the evident intention of consolidating the Clyde–Forth line as a frontier. ‘This neck was now secured by garrisons, and the whole sweep of country to the south was safe in our hands. The enemy had been pushed into what was virtually another island’ (Tacitus, Agricola, xxiii). Much of the military activity in the lowlands was concentrated in Selgovian territory, where presumably the main resistance lay. The old tribal centre on Eildon Hill may have been slighted at this time, and the principal Roman fort of the whole northern system was built close by at Newstead. The Votadini, on the other hand, were less harshly treated: fewer forts were established in their territory and their tribal capital on Traprain Law was allowed to remain in occupation. The Novantae of south-western Scotland, together with other more remote tribes, were the subject of a separate campaign in 82, at the end of which Agricola stood on the shore and looked across to Ireland, estimating that it could be conquered and held with a single legion and a few auxiliaries.

Figure 10.4 The Roman conquest of northern Britain. The military zone is stippled; black squares indicate legionary bases (sources: various).

So far the army had met with little organized opposition, but when in the next spring they moved north again along the eastern coastal plain beyond the Tay, Caledonian resistance began to harden. Even with the support of sea-borne supplies and reinforcements, Roman communications were seriously stretched, but gradually forts were established at the mouths of the glens to bottle up the tribesmen in the mountains, and the Roman hold strengthened. Once they had overcome their initial surprise at the speed of the Roman advance, the Caledonians began to organize a more aggressive resistance, culminating in the attack on a Roman fort which only narrowly escaped destruction. ‘With unbroken spirit’, says Tacitus, ‘they persisted in arming their whole fighting force, putting their wives and children in places of safety and ratifying their league by conference and sacrifice’ (Agricola, xxvii).

Thus by the beginning of the summer of AD 84 the scene was set for the final confrontation between the two armies at Mons Graupius. ‘The Britons, undaunted by the loss of the previous battle, welcomed the choice between revenge and enslavement… Already more than 30,000 of them made a gallant show, and still they came flocking to the colours’ (Tacitus, Agricola, xxix). To the Caledonians, pushed literally to the edge of Britain, this was clearly the last stand. As their war leader Calgacus is reported to have said in his pre-battle oration:

We, the last men on earth, the last of the free, have been shielded till today by the very remoteness of the seclusion for which we are famed… but today the boundary of Britain is exposed; beyond us lies no nation, nothing but waves and rocks.

Even if the actual words are those of Tacitus (Agricola, xxxii), it is tempting to believe that the sentiments are accurately reported.

The battle was fought, the Britons lost: the final organized resistance of free Britain had fallen and with it 10,000 British casualties. The last words must be left with Tacitus:

The Britons wandered all over the countryside, men and women together, wailing, carrying off their wounded and calling out to the survivors. They would leave their homes and in fury set fire to them… sometimes they would try to organize plans… sometimes the sight of their dear ones broke their hearts… The next day revealed the quality of the victory more clearly. A grim silence reigned on every hand; the hills were deserted, only here and there was smoke seen rising from chimneys in the distance and our scouts found no one to encounter them.

(ibid., xxxviii)