4

Regional groupings

An overview

The British Isles presents a varied landscape – a cluster of disparate ecozones within which societies have structured their existence. Sometimes and in some places similar attributes of culture were shared over considerable regions: on other occasions distinct cultural packages were strictly localized. Within this variation is embedded much information about identity and political systems, about the constraints of landscape and networks of communication, and about the relationship of the British community to developing world systems. It is the task of the archaeologist to identify patterns within the material evidence and to attempt to interpret them in terms of past communities and their trajectories of change. In this chapter we will consider, by way of introduction, some of the broader issues of regionalism. Subsequent chapters will look in more detail at different categories of evidence such as pottery styles, variation within settlement structures and patterns of exchange.

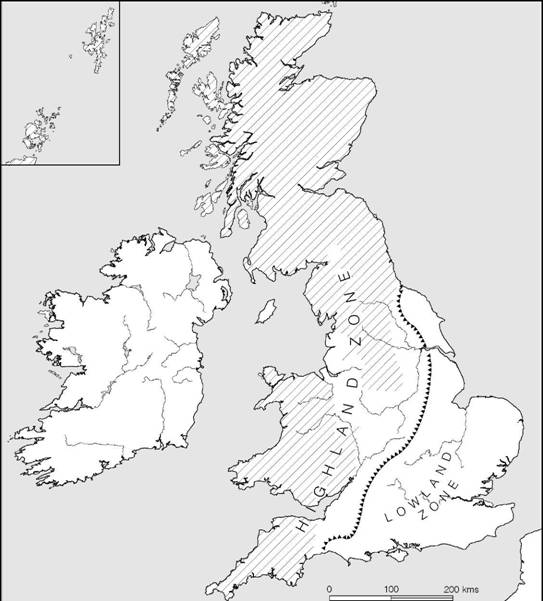

The geography of Britain and its relationship to the Ocean and the Continent have, throughout time, imposed a structure on human societies and will continue to do so. There are many ways of approaching questions. In the 1930s Cyril Fox argued that the country should be divided into a highland and a lowland zone, the divide running roughly from the western edge of the North York Moors to the eastern edge of Dartmoor and Exmoor (Fox 1932) (Figure 4.1). Although generally out of favour for a long while, because it was seen to be ‘geographical determinism’, the concept is not entirely without value in providing an explanatory background for broad regional patterning that can be recognized in the archaeological data. Lying behind Fox’s divide are three immutable factors which reinforce each other: the contrast between the old hard rocks of the north and west and the softer newer rocks of the south and east; the much moister climate of the west and north; and the different patterns of communication which bind the two zones, with the south and east looking to the Continent and the north and west to the Atlantic. These simple geographical truths provide constraints and opportunities which help to mould socio-economic systems.

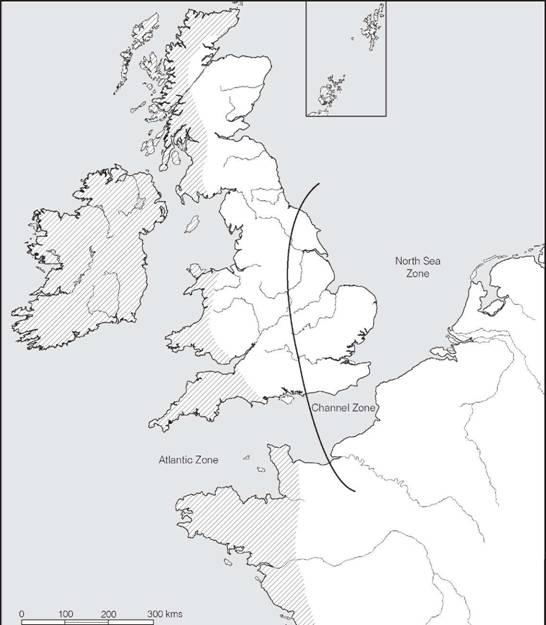

In attempting to understand the variety evident in the archaeological data for the Iron Age the Atlantic/Continental divide is an important construct (Figure 4.2). The sea provided an essential means of communication which, on the one hand, bound the south and east coasts of Britain to the Continent through an intricate network of exchange systems while on the other it provided a broad corridor of communication linking the Atlantic-facing communities of the island. The east–west divide thus created was a significant cultural fault line. There are other tantalizing hints that maritime contact around the south and east coasts of Britain may, from time to time, have bound distant communities together. These matters will be explored later in chapter 17.

Figure 4.1 The Highland and Lowland Zones of Britain (source: Fox 1932).

Simple highland/lowland or Atlantic/Continental divides are at best coarse-grained generalizations and it has to be realized that the British countryside is, in reality, a palimpsest of ecological micro-regions linked together by varied networks of communication. The work of historical geographers, studying the more recent periods, amply brings out the patchwork nature of the landscape and its dramatic effects on human populations during the last thousand years (Roberts and Wrathmell 2002). Studies of this kind show what can be achieved with a high- resolution database. The evidence for the Iron Age is, by comparison, uneven, partial and ill- focused. Yet that said, it does allow something of the cultural variation across the regions to be appreciated.

Figure 4.2 Zones of contact between Britain and the Continent (source: author).

Broadly speaking, evidence for regional variation falls into one of three categories: settlement form; artefact typology or style; and belief system. The first, settlement form, is largely a reflection of the socio-economic system which is itself closely controlled by geographical factors. Artefact typology and style variation work at rather different levels. Some artefact types, such as tools, weapons or élite gear, may be distributed over large areas through extensive networks of exchange at an élite level, while other commodities, such as containers for salt or quernstones, may owe their patterns of distribution to quite different economic imperatives embedded within social systems. Style preferences on the other hand – shown for example in pottery decoration or favoured types of personal ornaments – may well reflect a community’s sense of identity or kinship. The third category – belief systems – is more difficult to discern in the archaeological record, but when manifest in burial ritual it can be taken as an indicator of social coherence at a regional level.

To complicate matters further we have to contend with the trajectory of time: regional groupings identifiable in one period may be re-formed in another. To what extent this can be taken as evidence of social or political change has to be considered separately in each case.

Regional variation in settlement form: an overview

In chapters 12–14 extensive consideration will be given to the archaeology of settlement: here only the broad patterning will be outlined. Standing back from the detail it is possible to divide the varied settlement forms of Britain into four basic types (Figure 4.3). In the west and north, including the south-west peninsula, west Wales, western Scotland and the Western Isles, and the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland, the landscape is dominated by small strongly defended homesteads referred to now by a variety of names: rounds in Cornwall, raths in Wales and brochs and duns in Scotland. These settlements represent single family units and are often quite densely scattered throughout the landscape. Over much of eastern England and the Midlands open settlements, sometimes of considerable extent, seem to be the norm. Enclosures are also known throughout the area and some of them seem to represent clusters of several family units. Further north, stretching across the country from the Yorkshire and Northumberland coast to Cumberland, settlement is characterized by homesteads enclosed within palisaded or banked and ditched enclosures. Finally in southern Britain, the Welsh borderland and southern and eastern Scotland, the landscape is dominated by hillforts which must represent the communal activity of large groups of people. In addition to the hillforts there are a variety of settlements of various kinds, ranging from quite large enclosed farms in the south to strongly defended homesteads in the north.

A broad characterization in these very general terms is, inevitably, a simplification but it does reflect the variety evident in the settlement pattern across the country. Within each of the zones there is, of course, much variation from one region to another and there are also quite significant changes over time.

The differences we can recognize at this level of generalization seem to echo climatic differences between the wetter west and the drier east, suggesting that the two zones may have encouraged different agricultural regimes, and it is this constraint that may have determined the settlement systems. The hillfort-dominated zone of central southern Britain reflects a different socio-economic system which may be related in part to a distinctive regional subsistence strategy and in part to the frontier’ situation of this region between the two stable and deep-rooted systems to the east and west.

Figure 4.3 Zones of differing settlement form (source: author).

The broad regional system sketched out here holds good for the Early and Middle Iron Age, but towards the end of the second century BC changes begin to be apparent as the south-east of Britain is drawn closer and closer into the exchange network of the Roman world – a theme taken up in detail in chapter 10. From this time onwards significant changes can be detected, with the south-east developing large nucleated settlements (oppida) and the rural settlements taking on a more diffuse form, some of them becoming quite large. Coinage was adopted throughout this region, and by the first century AD it is possible to identify a core zone which had developed a quite sophisticated political and economic structure with a periphery of coin- using tribes around. Beyond them, in the north and west, life seems to have continued much as before.

It can be argued that this reorientation in the south-east of Britain was occasioned by the rapid development of trading opportunities with the Roman world. In other words a change in the political geography of Gaul empowered the communities of south-eastern Britain with new economic opportunities which, when realized, distorted indigenous regional trajectories.

Regional variation in bronze typology: eighth to fifth centuries

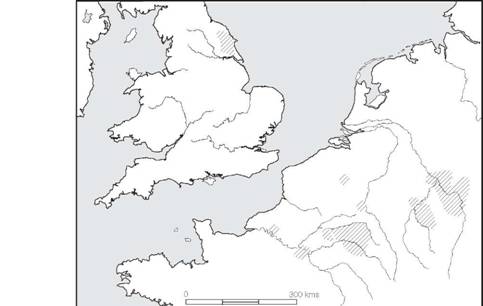

In the period from the eighth to the fifth centuries BC bronze was still widely used for the manufacture of tools and weapons and it is conventional to use bronze typology as a convenient way to divide the period into phases (Figure 2.2, p. 32). According to our present understanding of chronology, the early part of the eighth century saw the end of the Ewart Park tradition and the beginning of the Llyn Fawr phase which lasted to about 600 BC. Throughout this period the predominant weapon was the sword, first the British Ewart Park sword and later the Gündlin- gen type, most examples of which were made in Britain in imitation of Continental varieties. Another type of sword, known as the Carp’s-Tongue Sword, is also found in the south-east of the country early in this period but usually in scrap hoards with other distinctive material, suggesting the importation of recycled raw material from France. The two indigenous sword types are found quite widely distributed across the British Isles (Burgess 1969a, Figure 12), but among the other items made in bronze, most notably the socketed axes, a number of distinctive regional groupings can be identified (Figure 4.4).

The Carp’s-Tongue Sword tradition

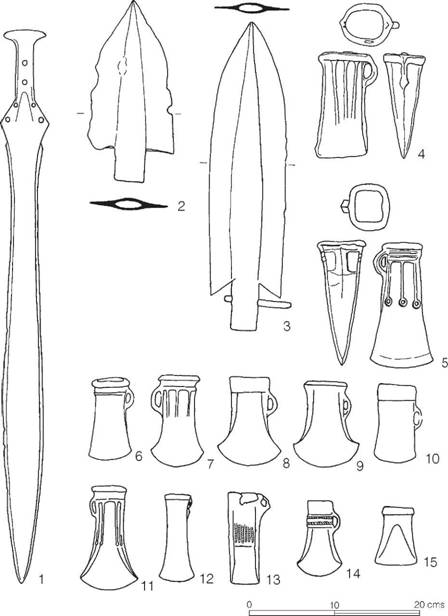

This assemblage, generally found in scrap hoards in the south-east of Britain, includes a highly distinctive sword type, with purse-shaped chapes, decorated spearheads, socketed axes, single- edged razors and a variety of decorative attachments (Figure 4.5). The hoards are concentrated in the Thames valley, East Anglia and Kent and along the Sussex coast, with a scattering extending into Dorset, a pattern which reflects the importance of the sea routes by which the scrap material is thought to have been transported to Britain. The distribution is closely comparable to that of the LBA Plain ware pottery and suggests that a large area of south-east Britain, bounded roughly by the Jurassic Ridge, shared in a broadly similar culture by the eighth century BC. After this, as we will see in the next chapter, this same region retains its identity. It remains a heavy pottery-using zone but it is now possible to subdivide it into a number of discrete regions based on distinctive local styles of pottery decoration (pp. 90–7).

Figure 4.4 Distribution of the major bronze traditions in the eighth to fifth centuries (source: author).

Figure 4.5 Implements and weapons of the Carp’s-Tongue Sword Complex: 1 sword from the river Thames; 2 socketed axe from the Thames at Brentford, Middx.; 3 socketed spear from Chingford, Essex; 4 knife from Eaton, Norwich; 5 ‘belt attachment’ from the Thames at Sion Reach; 6 chape from Leving- ton, Suffolk; 7 leather attachment from Watford, Herts. (source: Burgess 1969b).

The Llantwit–Stogursey tradition

In south Wales, principally Monmouthshire and Glamorganshire and spreading into Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, a group of related domestic bronze implements has been defined and named after two of the important hoards (Burgess 1969a, 19–21; also Fox and Hyde 1939, 390; Savory 1958, 37; McNeil 1973). Distinctive among the tools represented is the socketed axe with a heavily moulded lip, decorated with parallel ribbing on the two faces. The type is frequently found in association with a range of tools including socketed gouges and tanged chisels. Varieties of the axe also occur in the Llyn Fawr and Cardiff hoards together with horse harness- fittings indicating an eighth- to seventh-century date which is further supported by occasional associations with material of the Carp’s-Tongue Sword Complex. Scattered finds, a few hoards and occasional moulds for axes have turned up in south-west Britain, implying the use of the Severn estuary and western sea approaches for trading – no doubt in connection with the exploitation of Cornish tin – but the main distribution of hoards is centred upon south Wales. Pottery does not appear to have been a significant part of the material culture of this region.

The Broadward tradition

The Broadward group, named after a Herefordshire hoard, can be defined in terms of an assemblage of weapons which includes swords of Ewart Park type, chapes and spearheads, among which a barbed variety is characteristic (Burgess, Coombs and Davies 1972) (Figure 4.6). The contrast between the predominantly domestic character of south-east Welsh hoards and the military nature of the Broadward hoards may possibly reflect a difference in social structure. The area covered by the group extends from Pembrokeshire through central Wales into Cheshire and from there into the Welsh borderland, while some of the diagnostic weapons are found even further afield. The territory is well suited to a basically pastoral economy which would be consistent with a warlike society. The lack of pottery is another feature suggestive of pastoralism, since under such living conditions pottery would tend to break easily and would be better replaced by leather, wooden or metal containers. Indeed, there is clear evidence from the later forts in the Welsh borderland that the communities remained largely aceramic into the fifth or fourth century BC.

The Llantissilio tradition

The north of Wales appears to have been a technological backwater in the eighth to sixth centuries, receiving exotic types from Ireland and other parts of England and Wales rather than developing its own. A degree of conservatism is shown by the retention of the late type of palstave, which had been replaced by socketed axes elsewhere.

The famous Parc y Meirch hoard (Figure 17.7, p. 455 and pp. 451–4), containing horse harness-fittings of eighth- to seventh-century date, belongs geographically to this group. Its presence clearly demonstrates the extensive trading systems which, whether directly or indirectly via Ireland, allowed exotic north European objects to be transported to this relatively isolated territory.

Excavations on a number of north Welsh hillforts, in particular Moel y Gaer, Breiddin and Dinorben, have indicated a long tradition of occupation, extending back in some cases to c. 1000 BC and continuing largely uninterrupted throughout the first millennium, during which time defences were modified and internal structures were rearranged and rebuilt. The Breiddin has produced a particularly impressive range of plain coarse pottery, together with a number of items of Late Bronze Age metalwork representing occupation in the period 1000–700; but thereafter pottery and metalwork are sparse even though the radiocarbon dates indicate continued use. The hillfort of Moel y Gaer, which appears to have been constructed in the seventh or sixth century, is almost devoid of finds. Moel Hiraddug in the Vale of Clwyd produced several radiocarbon dates suggestive of occupation going back to the sixth and fifth centuries while the presence of a fine La Tène I fibula indicates occupation continuing into the fourth or third century.

Figure 4.6 Implements and weapons of various bronze traditions of the seventh to fifth centuries: 1 sword from Ewart Park, Northumberland; 2 spear from Broadward, Heref. spear from Plaistow Marshes, Essex; 4–15 socketed axes: 4 Llantwit Major, Glam.; 5 Leeds(?); 6 Dalduff, Ayr.; 7 Shetland; 8 Tomintoul, Banff.; 9 Culloden, Inverness; 10 Mawcarse, Kinross.; 11 Delvine, Perth; 12 Annan, Dumfries.; 13 Carse Loch, Kirkcudbright.; 14 Birse, Aberdeen; 15 Angus(?) (sources: 1–5 Burgess 1969b; 6–15 Coles 1962b).

The Heathery Burn tradition

Throughout the seventh and sixth centuries a well-defined bronzeworking tradition, called here the Heathery Burn tradition, served northern England.

The extensive collection of material from the Heathery Burn Cave, Co. Durham, may be regarded as representative of the range of artefacts in use. The maximum distribution of this range, typified by the Yorkshire type of three-ribbed socketed axe, was centred upon Yorkshire, Northumberland and County Durham with outliers in adjacent counties. The Heathery Burn deposit is particularly valuable, not only for its cart- and harness-fittings and bucket referred to below (p. 451), but also for the associated metal types, including a Covesea bracelet, a Ewart Park sword, spearheads of northern type, socketed knives and chisels, and a group of Yorkshire socketed axes. A fragment of copper ingot, a casting jet and half a bronze mould for a Yorkshire axe suggest the probability of local metalworking. Non-metallic finds from the cave include jet armlets, stone spindle whorls, a range of bone tools and fittings, and five sherds of pottery belonging to coarse-shouldered vessels with internally flattened rims.

There is a substantial overlap between the southern extension of the Yorkshire axe distribution, pushing down through Lincolnshire to East Anglia, and the northern part of the West Harling–Fengate and Staple Howe ceramic traditions defined below (pp. 94–6) on the basis of their distinctive pottery. At Staple Howe a Yorkshire axe, jet armlets and other items of the non- metallic material culture are shared with the Heathery Burn Cave, and again at Scarborough a Yorkshire axe was found on the settlement site. Such associations are a salutary reminder of the fact that groupings defined on ceramic grounds may have little relationship to those depending upon the distribution of bronze types. The two classes of evidence are seldom mutually compatible. Nevertheless, the dense distribution of the Yorkshire axes emphasizes a zone of contact from the eighth to the sixth centuries which deserves recognition (Burgess and Miket 1976). At present, however, it is difficult to compare the distribution of metal types to other cultural traits in the same region.

The Traprain–Hownam tradition

The eastern coast of northern England and Scotland, from the Tyne north to the Esk in the county of Angus, exhibits some degree of cultural unity which can be defined principally through the distribution of locally manufactured bronze implements such as the Traprain Law type of socketed axe (Coles 1962b) and British varieties of Hallstatt swords. To these should be added imported Hallstatt types, including a Hallstatt sword (Cowen’s class b) from Cambusken- neth, Stirling, the Horsehope cart- and harness-fittings, the Adabrock bronze bowl (Figure 4.7), razors from Traprain Law and Kinleith, Midlothian, and a group of sunflower swan’s-neck pins (Figure 17.16, p. 466). Evidently close contact was maintained with mainland Europe throughout the period, allowing a wide range of exotic material to reach this part of Britain.

Figure 4.7 The Adabrock bronze bowl, Lewis (source: Coles 1962b).

Within this region a number of settlement sites have been discovered and a few excavated. Mostly they are palisaded enclosures containing one or more circular timber huts. Radiocarbon dates suggest occupation began in the seventh to sixth centuries. These early settlements and their sparse and virtually aceramic material culture have been used to identify the Hownam culture (MacKie 1969a, 21).

The Covesea–Abernethy tradition

Between the Firth of Forth and the Moray Firth, and overlapping with the northern distribution of the Traprain–Hownam sites, lies the Covesea–Abernethy group, which can be defined by both metal implements and distinctive techniques of hillfort construction. The metal types include the Covesea armlet with unevenly expanded terminals, a type thought to have been imported into Britain from northern Europe in the eighth to seventh centuries together with the pendant necklets of Braes of Gight and Wester Ord (Coles 1962b, 39–44). Locally made products are also represented, including the short socketed axes with heavy multiple neck-mouldings, named after the Meldrum hoard, which are found in eastern Scotland, mainly but not invariably north of the Forth.

From the Sculptor’s Cave at Covesea, Moray, and Balmashanner, Angus, metalwork has been found in association with a widely distributed group of pottery belonging to the rather generalized flat-rimmed class. The north-east Scottish group of pottery belongs to the rather generalized type named Covesea ware, and is thought to have ultimately originated in northern Europe (Coles 1962b, 44). If this derivation is correct, it might suggest some form of folk movement into north-east Scotland in or about the seventh century, introducing both pottery and the new metal objects, but such a view is difficult to substantiate.

While the bronzeworking traditions were eventually replaced by ironworking, other aspects of the material culture together with the timber-lacing of forts continued in use over many centuries, giving rise to a broad continuum sometimes known as the Abernethy culture (MacKie 1969a, 16–21).

It will be evident from the foregoing paragraphs that the Traprain–Hownam tradition and the Covesea–Abernethy group have much in common. Hallstatt and Hallstatt-derived artefacts extend far into the Covesea–Abernethy region and the characteristic palisaded settlements are now being discovered north of the Firth of Forth. Similarly, Covesea-style flat-rimmed pottery has been found at an occupation site at Green Knowe in Peeblesshire, well within the distribution patterns of the Traprain–Hownam group, and indeed a variety of flat-rimmed pottery is also known from Traprain Law itself. The distribution patterns of the Meldrum and Traprain Law axes also overlap, the Meldrum type extending across most of eastern Scotland from the border to the Moray Firth. In view of such a widespread similarity, it might be thought to be more reasonable eventually to treat the entire area as a single east Scottish group, abandoning the conventional terminology of a Tyne–Forth Hownam culture and a north-eastern Abernethy culture (MacKie 1969a, 20).

The Atlantic Province

The bronze tradition of the Atlantic Province is not well known, owing to a paucity of finds, but a bronze smith had established himself in one of the buildings at Jarlshof in Shetland, his presence indicated by fragments of clay moulds for swords, socketed axes and sunflower pins. The Jarlshof discovery raises interesting questions of mobility: was the smith an itinerant, one of a small group of specialists moving among the Northern and Western Isles or was he a permanent resident?

Regional aspects of material culture

In reviewing the surviving material culture of Iron Age date from the British Isles a sharp disparity can be recognized between material-rich and material-poor zones, always remembering of course that the organic component of the material culture – wood, leather and fabrics – does not normally survive except in waterlogged conditions. In very broad terms it can be said that the south-east of the country, south and east of a line from Swansea Bay to the mouth of the Tees, together with the Western and Northern Isles, is material-rich while the rest of the country is material-poor. But like all generalizations there needs to be some qualification. Much of the landscape of the material-poor zone is less congenial for settlement, and archaeological investigation has been significantly less intensive here, but, that said, many sites have been excavated on comparatively large scales, especially in south-eastern Scotland and Northumberland and Durham. Compare them area by area with their south-eastern counterparts and the dearth of material finds becomes very noticeable.

The phenomenon is of some potential interest but convincing explanations are not immediately apparent. Many years ago Stuart Piggott saw the contrast in terms of different production modes, the south-eastern economy being based on cereals while the northern economy was focused on pastoralism (Piggott 1958). Nearly fifty years of excavation, fieldwork and environmental studies have shown this to be too gross a simplification, not least since cereal production is well in evidence in the north, but it remains a distinct possibility that the economies of the two regions were differently balanced, with grain growing being maximized in the south where the climate was more congenial, facilitating the production of surpluses for exchange. This in turn may have led to social complexity, involving networks of exchange demanding a more varied material culture. If this is so then the economy and material culture of the northern zone may have reflected a simpler and more self-sufficient socio-economic system, and one more reliant on organic materials appropriate to the degree of mobility occasioned by a more livestock-oriented mode of production.

Another factor which may be relevant, at least in some part, is a difference in belief systems. In the south-east there is abundant evidence that the deposition of goods through propitiatory acts was deeply embedded in social behaviour (pp. 566–72) whereas in the northern zone such ‘offerings’ appear to be very much rarer. We argue later that in the south much of this propitiatory behaviour was associated with rituals ensuring the fertility of grain. A very high percentage of the material culture from southern sites can be shown to come from propitiatory deposits. It could, therefore, be argued that the belief systems prevalent in the south actively encouraged production. At the same time they mitigated against the recycling of materials and enhanced the chance of archaeological discovery.

The contrasts between the material-rich and material-poor zones are striking. They clearly reflect marked differences in social, economic and belief systems. We should not, however, characterize the northern zone as ‘culturally impoverished’ – it may indeed have had a very rich material culture of woodworking, ornate leatherwork and elaborate woven fabrics – but it was culturally different, and in that difference lies an area of very real interest which deserves far more attention than it has hitherto received.

Identifying immigrant communities

Until about 1960 it was widely accepted that Britain had, during the Iron Age, received a number of immigrations from the Continent each introducing significant numbers of people sufficient to make a cultural impact on the indigenous population. As we have seen in chapter 1, these supposed immigrations provided the basis of the classificatory framework for the Iron Age. Grahame Clark’s famous attack on invasion hypotheses in British prehistory in 1966 dealt a death blow to the entire edifice, and in the decade of cheerful iconoclasm that followed all thought of immigration as the prime mover of cultural change was abandoned. Instead the indigenous nature of the British Iron Age was given great stress. As in all matters of this kind, the pendulum has swung too far. There can be no doubt at all that the communities of the south and east of Britain were in frequent, if not constant, contact with the adjacent Continent. The sea must at times have teemed with shipping. In such periods of interaction there may well have been a trickle of immigrants who would have merged imperceptibly with the native communities. On some occasions larger groups may have arrived, but unless they were numerous enough and determined enough to have maintained their alien identity over several generations they are unlikely now to be archaeologically visible, and their cultural contribution, like their genes, will have been absorbed into the indigenous pool.

Of all the ‘invasions’ and ‘migrations’ enthusiastically proposed in the formative years of Iron Age studies there are only two which seem to retain some possible credibility, the migration of an Early La Tène élite from north Gaul to Yorkshire in the fifth century BC and the arrival of settlers from Belgic Gaul in the late second or early first century BC. The question of the Belgae is bound up with the extensive comings and goings across the Channel in the Late Iron Age and will be considered below (pp. 126–7) in that broader context, but the matter of the Early La Tène community in Yorkshire is relevant here since they constitute an archaeologically distinct group.

The Arras group

Most Early La Tène contacts between the Continent and southern Britain were on the basis of casual trading and exchange, but in eastern Yorkshire it is possible to distinguish a group of burials which have close connections with northern Gaul, allowing the possibility of some form of intrusive folk movement bringing with it burial traditions alien to those of the indigenous culture (Figure 4.8, also pp. 546–9). These new burials are conventionally referred to as the Arras culture, after the Yorkshire barrow cemetery partially examined for the first time in 1815. The Arras cemetery provides evidence of most of the rites characteristic of the Yorkshire burials: there were several inhumations buried with the remains of carts; some were covered by barrows constructed within rectangular ditched enclosures; the barrow mounds were invariably small; and the cemetery was large, containing between 100 and 200 graves. These elements are repeated on a number of sites, the more important of which include Dane’s Graves, Driffield, Eastburn, Cowlam, Pexton Moor, Hunmanby, Huntow, Sawdon, Burton Fleming, Garton Slack and Wetwang Slack.

A distributional analysis of the rite of cart burial shows that two distinct methods were employed: either the carts were placed upright in the graves, sometimes with recesses cut for the wheels so that the body of the cart could rest on the ground surface; or the carts were dismantled, the wheels being placed flat. That burials of the first type were found on the limestone hills, while the second were restricted to the Wolds, suggests the possibility of some form of cultural distinction between the two areas – a suggestion further supported by the apparent absence of large cemeteries, as opposed to isolated barrows, on the limestone hills in reverse of the situation on the Wolds.

The surviving grave-goods can be divided into two groups: the cart- and harness-fittings, and personal ornaments and offerings. The first category covers a wide range of types including iron cart-tyres, nave hoops and miscellaneous wheel-fittings, linchpins to prevent the wheels from coming loose, bronze pole sheaths, three-link horse-bits and various terret-rings from the leather harnesses. Detailed comparisons with Continental types (Stead 1965, 28–45; 1979, 7–39) show that while the British versions were closely related to them, they are nevertheless sufficiently distinctive to be considered the result of several generations of local development. Not one of the cart- or harness-fittings at present known can be regarded as a direct import from France.

Among the ornaments, on the other hand, there is an assemblage from Cowlam which is clearly of direct Continental inspiration. It includes a fibula of Münsingen Ia type, a bracelet with ‘tongue-in-glove’ terminals, expanded at five points around the circumference, which can be paralleled in Alsace and Burgundy in Early La Tène contexts, and a necklace composed of seventy blue and white beads. Again, parallels can be found for such necklaces in the phase Ia graves at Münsingen although they do occur later. The Cowlam burial is the earliest assemblage that can be defined within the Arras culture, probably dating to the early part of the fourth century: it might reasonably be thought to represent the burial of first-generation imported trinkets. The Cowlam bracelet and necklace are similar to finds from the Arras cemetery, where knobbed and ribbed bracelets of Early La Tène type provide a further link with Burgundy and Switzerland. The remainder of the ornaments – the inlaid and involuted brooches, the incised bronze mirror, the ring-headed pins, finger-rings, pendants, toilet sets and toggles – all belong to a decidedly British tradition and must be later developments influenced more by internal British traditions than by Continental ideas.

Figure 4.8 Early La Tène vehicle burials (sources: various).

It is a distinct possibility that the Arras culture arose as the result of a folk movement into eastern Yorkshire late in the fifth or early in the fourth century. Thereafter local development modified the culture, but as late as the first century BC its alien origins were still apparent. A careful consideration of the niceties of burial rite and the typology of the earliest group of artefacts has led Stead (1965) to propose a complex origin for the invaders, coming from the Burgundian area (where dismantled carts and the absence of weapons and pottery are similar to the British burials) via the Seine. In the Nanterre–Paris region part of the band remained to give rise to the Parisii, while those destined for Britain moved on, to found another community in Yorkshire, known to Ptolemy as the Parisi: the coincidence is noteworthy. The cultural affinities of the Pexton Moor burial, with its rectangular enclosure ditches and wheel pits, may however indicate that some part of the immigrant force had connections with the La Tène group in the Champagne. The alternative view, that the Arras phenomenon was a local development, the aristocracy adopting ‘foreign’ burial rites as a means of expressing status, has been persuasively argued by Higham (1987).

A close study of the Arras culture emphasizes some of the problems involved in recognizing immigrant communities by means of the archaeological record. Seldom is it possible to discover material of the first generation; what survives is more likely to belong to subsequent developments, which invariably diverge from the traditions of the homeland. Nevertheless, the Yorkshire evidence is impressive. It suggests small bands arriving, with little more than their personal equipment, and settling down among the natives in whose pottery traditions they shared. When time came for burial they maintained their own rituals, using a mortuary cart to bring the body to the grave and sometimes burying it with the dead. So strong were these religious practices that they remained dominant for several hundred years.

The debate has been further extended by the discovery, in 2001, of a single two-wheeled vehicle burial at Newbridge, just west of Edinburgh airport. The vehicle was buried intact, with its wheels accommodated in slots cut into the grave bottom. The associated harness-fittings in iron have close similarities to Continental types while a radiocarbon date of between 520–370 BC supports an Early La Tène date. Interpretation of an isolated find of this kind is difficult but it is tempting to see it as support for the idea that immigrants from northern Gaul, albeit in small numbers, may have reached many parts of eastern Britain but only in Yorkshire was their distinctive burial rite adopted.

Summary

Sufficient will have been said in this chapter to give some idea of the problems involved in attempting to discern regional patterns lying beneath the bewildering mass of archaeological data now available. Patterns, albeit very incomplete, can be seen at all levels from the very broad distribution of settlement form to the very local distribution of a distinctive artefact type made by an individual craftsman. Different patterns have different meanings, and the true meanings, in contemporary social terms, are impossible for us now to hope to discover. At best the patterns we can recognize offer a structure which helps to contain the evidence.

All that said, the Iron Age landscape is likely to have been a vast patchwork of distinct social groups. Some will have retained a strict identity with agreed boundaries, adopting behaviour and overt symbols proclaiming their oneness and their differences from their neighbours. The Arras group, with their preference for a particular set of burial rituals, would seem to be a good example of this. But for much of the country the differences between the polities seem to be far more blurred, though this may be because of the limitations of the archaeological evidence. Only in the case of the ceramic evidence, to be reviewed in the next chapter, is it possible to glimpse the discrete patterns which may have come about as different polities, mainly in the south-east of the country – the material-culture-rich zone – found it necessary to express their ethnicity.