Before April 12, 1955, polio was one of the most feared diseases in the United States. The virus, which struck mostly infants, killed about 5 percent of its victims and left the rest with crippling, permanent paralysis in the arms or legs. In 1952, the worst year of the polio epidemic ever recorded, polio killed 3,000 children in the United States and crippled another 55,000.

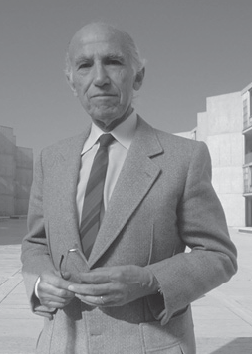

But on that day, a New York City–born doctor, Jonas Salk (1914–1995), made front pages around the world with the announcement that he had invented a successful polio vaccine. The impact of the polio vaccine was enormous; by 1969, no deaths from the virus were reported anywhere in the United States—one of the greatest public health triumphs in medical history.

Salk was born into a poor immigrant family in the Bronx. His father, Daniel, was a garment worker, and Salk attended public schools. He received his medical degree in 1939 and spent World War II developing a flu vaccine for US troops.

After the war, Salk shifted his efforts to polio, directing a team of researchers at the University of Pittsburgh. Known for his intense and demanding personality, he raced against dozens of other scientists to complete his vaccine in 1954; it was tested for a year before the successful results were announced to the public.

Salk won immediate acclaim as a national hero, but his place within the scientific community has been more controversial. Critics accused Salk of taking too much credit for the work of others, especially the polio researcher John Enders (1897–1985), whose work was a critical component of Salk’s vaccine. In part due to the controversy, Salk never achieved full recognition from the American scientific establishment. To overcome his ostracism from the medical community, he founded the Salk Institute for Biological Studies; “I couldn’t possibly have become a member of this institute if I hadn’t founded it myself,” he joked.

Salk remained involved in medical research for the rest of his life; at the time of his death at age eighty, he was working on a vaccine for AIDS at the Salk Institute.

ADDITIONAL FACTS

- In 1970, after divorcing his first wife, Salk married Françoise Gilot (1921–)—who was already famous as the former mistress of painter Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

- In a sign of the urgent nature of the race to develop a polio vaccine, Salk was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1954 under the headline “Is This the Year?”

- Salk was so confident in his work that he inoculated himself and his three sons with the vaccine in 1952—three years before it had been proven effective in scientific studies.