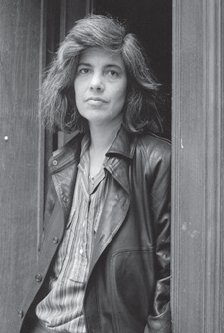

One of the leading figures in American intellectual life in the late twentieth century, Susan Sontag (1933–2004) wrote plays, novels, short fiction, and literary criticism. In her voluminous works, she sought to bridge the worlds of pop culture and high culture—and became a famous figure in both.

Sontag was born in Manhattan and graduated from the University of Chicago. At age seventeen, she married a sociology lecturer at the school, Philip Rieff (1922–2006), with whom she had her only child. The family later moved to Boston, where Sontag earned master’s degrees in English and philosophy from Harvard.

The couple divorced in 1958, and Sontag returned to New York, where she taught and wrote essays for small intellectual journals such as Partisan Review, Commentary, and the New York Review of Books. The article that propelled her to fame, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” was published in Partisan Review in 1964.

“Notes on ‘Camp,’” which caused a sensation in the New York intellectual world, was a defense of so-called low culture, or camp. Sontag praised camp—frivolous art, sometimes purposely done in bad taste and often associated with the gay community—for its “comic vision of the world.” “The whole point of Camp,” she wrote, “is to dethrone the serious.” Justifying popular culture to high culture, and vice versa, would be a recurring theme in Sontag’s criticism.

Sontag also wrote three novels, Death Kit (1967), The Volcano Lover (1992), and In America (2000), which won the National Book Award. Her short story “The Way We Live Now,” published in 1986, is regarded as one of the best pieces of fiction about the AIDS epidemic. Outspoken in her political views, Sontag was an opponent of the Vietnam War, a supporter of Western intervention in Bosnia in the 1990s, and a critic of US foreign policy after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York.

Sontag’s last essay criticized American mistreatment of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. She died in New York at age seventy-one.

ADDITIONAL FACTS

- Sontag was born Susan Rosenblatt. She changed her name after her father died and her mother remarried an army officer, Nathan Sontag.

- Before her death from a rare blood cancer, Sontag survived cancer twice and wrote a book, Illness as Metaphor (1978), inspired by her struggle against breast cancer in the 1970s.

- Sontag attracted international attention by directing a production of Waiting for Godot in war-torn Sarajevo in 1993. The choice of the absurdist play, which revolves around the expected arrival of a man named Godot, was seen as an allusion to the city’s desperate wait for Western intervention in the Bosnian war of the mid-1990s.