In the annals of invention, Cai Lun (c. 62–121) is rarely mentioned. But the product the ancient Chinese government official is credited with perfecting—paper—has undoubtedly changed the world.

Before paper, ancient scribes depended on papyrus, a fragile reed that decayed easily, or parchment, a rare and expensive product made from animal skin. Both cheap and durable, paper made it possible to keep far more extensive records and greatly lowered the cost of producing books. Papermaking gradually spread across the world, even contributing to the European Renaissance by making widespread literacy practical.

Originally from Hunan province, Cai Lun was an imperial eunuch in the court of the Han dynasty emperor He (79–105). (Castrated men were preferred for imperial service because they had no children and thus were thought to be less likely to attempt to overthrow the government and start a new dynasty.) In 89, Cai Lun was put in charge of the department that produced weapons and other instruments, where he quickly grasped the need to produce a cheap and reliable writing medium.

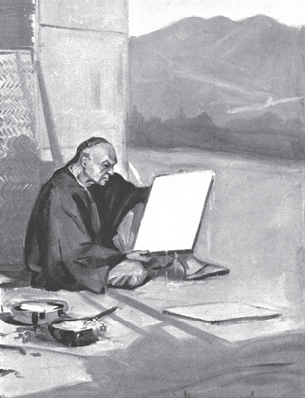

After years of experimentation, he unveiled his invention to the emperor in 105. It is thought that Cai Lun borrowed from earlier papermakers and local traditions, but it was his version of paper that became popular and eventually spread throughout the world.

Although he was hailed in his lifetime, Cai Lun’s glory did not last. The emperor died in 105, and his nephew, Emperor An of Han (94–125), turned on many of his father’s advisors after assuming the throne. About to be sent to prison, Cai Lun committed suicide in 121.

ADDITIONAL FACTS

- The Han dynasty lasted until AD 220 and had such a large influence on Chinese culture that Han became a synonym for people.

- Cai Lun was given the honorary title Marquis for his invention, and he was venerated for centuries afterward in China as the patron saint of papermaking.

- Chinese emperors kept the technique of papermaking a closely guarded secret for centuries after Cai Lun’s death. According to tradition, the secret was finally revealed in 751, when several Chinese papermakers were captured after a battle with Arabs and forced to divulge the recipe.