Chapter 6

No Justice? No Piece!

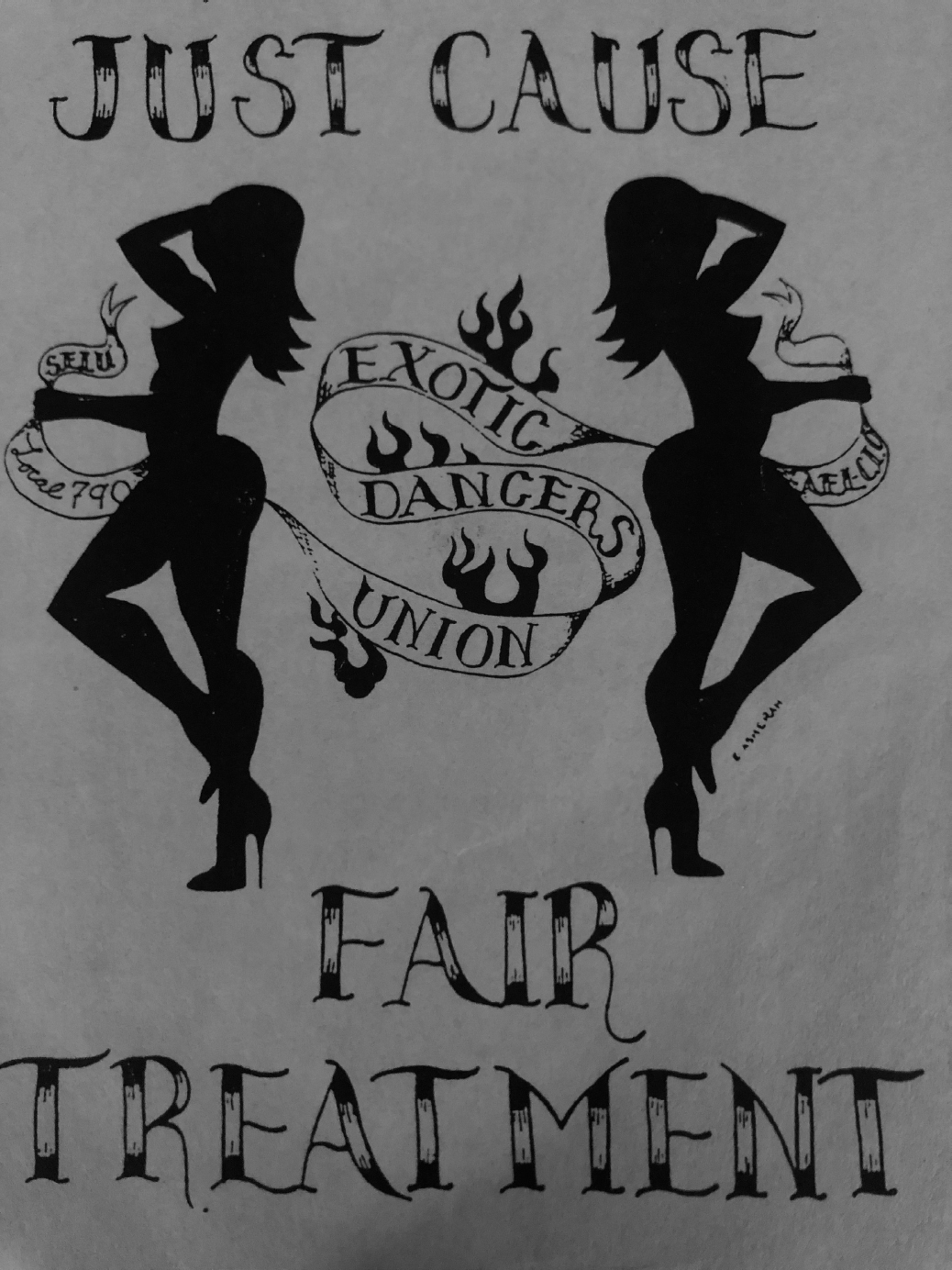

Flyer from our picket/lockout. Art and lettering by Ellen Asherah.

Courtesy of the author

Back at the Lusty, our unionization campaign was heating up, and management’s counter-campaign was intensifying. They hired a bunch of new dancers in an attempt to tip the vote against unionization, then posted flyers on pink paper decorated with smiley faces and addressing dancers in simple, paternalistic language: “This vote is very important as it may affect your job for a very long time,” and “We have arranged a secret ballot election for you.” Most dancers rolled their eyes at these messages, but we knew that some—especially those recently hired and unfamiliar with the history of the conflict—might be swayed by management’s posturing as a kindly, beneficent force shielding them from the malevolent union, so we struck back with our own messaging. I made a poster for the dressing room. Titled “Wanna Be a Porn Star?” it reminded dancers (a bit hyperbolically) how things were before the removal of the one-way windows. My hand-drawn cartoons, cut and taped under the text, showed a side view of a cartoon dancer bending over in front of a window. On the other side of the glass I’d drawn a menacing, stick-figure camera crew, with an old-fashioned, two-reel film camera, a megaphone marked “Director,” and a key light aimed at the unsuspecting dancer’s naked ass. The words Lights! Camera! Action! punctuated the little scene. The poster’s text urged my fellow dancers to “Vote ‘union yes’ to prevent the return of the one-way windows.”

Tara, a skilled tattoo artist, created an icon for our posters—two silhouetted mudflap girls in heels holding a ribbon-style banner reading “Exotic Dancers Union.” Jane, our minister of propaganda, refuted each of management’s attacks in her signature Snarxist prose style that was simultaneously sophisticated and clear, but also rife with dry humor and sarcasm: “We . . . hear management tell us the union is really some kind of self-interested outside force, eager to make promises it can’t keep, and then rob us of 13 bucks a month in dues.” She called management’s tactics “Orwellian” and “specious” and depicted management’s attorney, Robert Byrnes, with a cartoon picture of Homer Simpson’s villain boss, Mr. Burns. Throughout that summer, we kept our coworkers informed and inoculated against management’s attacks using cartoons, flyers, Q&A brochures, and letters of support for our union from local organizations and city officials. Some of our coworkers whizzed past the various postings without a second glance, while others hissed with annoyance when they sat down to a makeup mirror plastered with propaganda, but each day, I saw people shaking their heads angrily while reading Jane’s reports of management’s latest actions, or nodding and laughing at her witty responses.

We were careful to keep our information blitz internal, worried that media attention at the theater would threaten the very privacy we were fighting to defend. At the same time, we were feeling powerful and hopeful and also wanted to encourage dancers at other clubs, where conditions were much worse, to learn about our effort and begin organizing as well. We also knew that news of our campaign would reach the media sooner or later, so we decided to take control of when and how that happened by scheduling a group interview with a reporter from the San Francisco Examiner shortly before the union election.

Jane, Velvette, Naomi, and I met with Eric Brazil, a journalist, in a conference room at SEIU and explained what our workdays were like, and the grievances we were raising. But when we informed him that we wanted to use our stage names, not our real names, he closed his notebook and shook his head. “I can’t do a whole story based on unnamed sources.”

“But we’re not unnamed,” I said. “These are the names we go by.”

“There’s no way my editor will allow this.”

“Look,” I reasoned. “Within the context of our workplace, these are our names. Our bosses know us by these names, and so do our coworkers and our customers.” Eric continued to look skeptical. Sanda, the young organizer whom SEIU had assigned to work with us, shrugged. “We can take it to the Chronicle if you won’t print it,” she told him, referring to the Examiner’s competing daily. The writer sighed and opened his notebook. There was no way he was getting scooped on breaking the story of the world’s first strippers’ union. “Okay. So it’s Polly,” he said, looking at me.

The story was factual and serious and accompanied by a pro-union editorial piece. This first coverage worked like an incantation, calling up the devil from below. The morning after the story broke, reporters, camera crews, and TV vans lined Kearny Street. At the bottom of Telegraph Hill, at Pacific and Kearny, I ran into Wendy and Peace, hiding and peeking around the corner.

“They’re everywhere!” Wendy hissed. “How are we gonna get in?”

“I’m gonna get canned if I’m late to work again,” whispered Peace. “But I don’t want my face on the news.”

We watched from our corner as Honeysuckle approached the theater from the other end of the block, big, googly third eye stuck to her forehead, all ripped pink tights and tangled, newly green hair. Reporters swarmed up the hill toward her shouting questions. Seeing our chance, we hustled up the hill while the reporters were all running toward Honeysuckle.

For the next few weeks, reporters called the theater and the union office regularly, asking to speak to dancers about the unionization drive. I’d volunteered as a press contact, so SEIU would refer journalists to me during this period. I learned to keep them focused on the labor issues by figuring out my message ahead of time, saying only what I wanted them to write, and repeating it. Sometimes the interviews were productive, even thoughtful, as when a radio journalist from New York was surprised to find me articulate and well educated.

“Polly, you seem like a pretty smart girl. How did you get mixed up with a bunch of strippers?” How did I get mixed up with an asshole like him? was a better question.

“Actually, Dick, the majority of the dancers at the Lusty Lady have college degrees or are in college.”

“Well, I find that hard to believe. But, come on, isn’t this whole industry just about exploiting women?”

“That may be, Dick, but if you’re concerned about women’s exploitation, then think about it: starting a union is our way of fighting that exploitation. We’re standing up for our rights and standing up for each other. Without a union, yes, women in the industry are pushed to do more and more degrading work for less and less money, and that’s just a race to the bottom.”

“Thank you, Polly, union organizer for the Lusty Lady Theatre in San Francisco, where exotic dancers are forming a labor union.”

Other interviews were a waste—radio shock jocks, and misogynistic late-night talk-show hosts. Before I knew better, I agreed to talk to the “morning zoo” pair—Casey and the Bone—who laughed and joked through the entire interview.

“What are you going to ask for in your contract?” Casey asked.

“Free bikini waxing!” shouted the Bone, gleefully.

“Well, racial discrimination is quite pronounced in the sex industry, so we’re hoping—”

“How about a clause saying no more than one girl can be named Trixie?” Casey said, guffawing, while the Bone laughed in the background, adding, “A medical policy that covers boob jobs!”

“Actually, basic medical insurance is one of our primary goals. Currently, we don’t have any health coverage and—”

“Heated poles!” shrieked the Bone.

I hung up.

Even legitimate press inquiries trivialized our struggle. TV reports were frequently punctuated with little jokes and puns you’d never hear about autoworkers or nurses—“Where are they going to put the union label?” was a favorite. And journalists’ questions often seemed driven not by interest in the issues but by simple prurience. I was willing to exploit this to get the word out about what we were doing, and to encourage other dancers to follow suit, or to pressure our management to dial back their anti-union tactics, but after the first few interviews, the experience began to feel remarkably similar to my work in the Private Pleasures booth. Indeed, some of the reporters’ questions—“What’s your real name? How old are you? You seem so intelligent; how’d you get to be a stripper? What does your boyfriend think of your job?”—were identical to those asked by my customers. The difference was that one group paid for my time while the other did not. So I came up with a strategy for walking the line between publicizing our struggle and working for free: when journalists contacted me, I invited them to interview me during my shift in Private Pleasures. It was a perfect interview setup, really—quiet and private, but also right on-site, so they could get a real idea of the kind of work we did.

A reporter from the LA Times was to be my first experiment. When she called, I told her I’d be working the next day onstage from 12:30 to 2:30, and then in the Private Pleasures booth from 3:00 to 4:50. I suggested that she come by toward the end of my stage shift to have a look at the show and the rest of the theater, and then visit me in Private Pleasures where we could talk freely. I let her know that she’d have to pay just like everyone else, and she agreed that this seemed fair. The next day, a corner booth window slid open to reveal a young woman, unaccompanied, fully dressed, pen poised above open notebook. Unlike most of the female visitors to the Lusty Lady, she neither giggled, nor glared, nor ridiculed us. Instead, she looked around with interest, coolly observing the dancers and the structure of the space, jotting down a note or two. I waved, introduced myself, and performed my usual, explicit show in front of her window. When she tried to speak, I told her I couldn’t hear her, but that I would meet her in the Private Pleasures booth at 3:00 and we could talk then.

About forty minutes later, I set up in Private Pleasures and pulled the curtain to the hallway. She was standing out there waiting, so I waved her into the customer side of the booth and closed the hallway curtain. She had a ten-dollar bill in her hand and looked around for where to put it. I pointed to the bill acceptor, she put the money in, and I punched the microphone/timer button twice.

“Hey, Carla?”

“Yeah. Hi.” She was looking around the booth, checking out the logistics.

“Hi there. Good to meet you. What did you think of the stage show?”

“I was surprised at how . . . gynecological it was.” I laughed out loud at her tactful characterization of the show.

“So was I!”

“It makes you think, huh?”

“You mean about how we’re told we need to do all this shit in order to attract men, but in reality all you have to do is bend over in their face?” I replied. Now she laughed at the speed and precision with which I’d measured, pinned, and sewn up the idea for which she’d been grasping.

“Exactly! Yes.”

We chatted until her time ran out. She put another twenty in and we chatted some more. She asked thoughtful questions and took notes, fully dressed in the dark masturbation booth. I responded in my underwear, reclining on a satin pillow under the warm lights. By the time we finished the interview, men were queued up outside the door to Private Pleasures. They stared as she exited, flipping her notebook shut and waving to me. They all turned and watched her walk down the hall toward the theater exit. I went on with my afternoon as usual—pulling one curtain to and another one fro, punching a button, standing, stripping, kneeling, reclining, and starting all over again.

Carla’s article was great. It began with a cheerful description of me performing onstage while wearing a union pin on my garter belt, then detailed our organizing effort and grievances. It appeared in the LA Times on the first day of our union election, August 29, 1996, when two NLRB election monitors set up a polling station in the show directors’ office, next to our dressing room. The specially requested, all-female NLRB team monitored the ballot boxes in shifts over the course of two days, staying until midnight so that even dancers working the midnight to 4:00 A.M. shift would have an opportunity to vote before they went onstage. My own shift ended early in the day on the thirtieth, but I returned to the theater to witness the counting of the votes late that night, anxious to learn whether all the work of the past six months had been worth it—the secret meetings, the urgent, whispered, naked organizing in the dressing room, the union cards slipped stealthily into lockers, the fear of being found out and summarily fired. I thought about what I’d do if we lost. I wouldn’t have a choice, probably. They’d find an excuse to fire me, and I’d probably be blacklisted for my organizing work at the other clubs in town. Well, Gypsy Rose Lee was blacklisted, I told myself. I’ll be in good company.

An NLRB staffer unsealed the box and began pulling out ballots and reading each yes or no out loud. After reading each one, she would pass it to Collette, management’s designated witness, and Collette would pass it to Velvette, our appointed monitor. Once they had both acknowledged the vote, a second NLRB rep would tally the response on a count sheet. Jane, Tori, and I were also there making our own tally sheet just in case the vote was close, or there was any doubt about the outcome.

Listening to the count, I thought I heard a lot of yeses. I looked over at the ballot box, then at the pile of counted ballots in front of me on the desk. Halfway there. Were all the no ballots at the bottom of the box, waiting in ambush? Were all those anchormen and radio jocks right about a strippers’ union being a silly, quixotic notion?

The pile of counted ballots before me had grown. The ballot box was nearly empty.

“And . . . last one.” The monitor lifted the last ballot from the box and unfolded it. I held my breath.

“Yes.”

I turned to the NLRB rep tallying the votes. Her pen moved down her list. “Fifty-seven yeses. And . . .” She looked at her tally sheet and her pen and lips performed another silent incantation. Then: “Fifteen nos.”

Velvette, Tori, and I let out a spontaneous, synchronized cheer. Stoic, brainy Jane, who usually saved all her passion for scathing polemics against capitalism, smiled a rare, unchecked grin, teeth and all. Tori opened the office door and the four of us scattered through the theater in different directions like a bright fan of fireworks bursting into the night sky—I to the stage, Tori and Velvette to the dressing room, Jane to the front desk—“We won! We won! We won!” I reached the stage door and yelled the news to the dancers up there—Amnesia, Sorcia, Cinnamon, and Tara. They turned away from their windows and began jumping up and down, embracing, and spinning around the pole in delight. I ran onto the stage fully clothed—my stripper’s anxiety dream come true—and joined the hugging, cheering, laughing, and then the slow collapse into relief.

Once we’d finished celebrating, we started talking contract. In early September, we called a rank-and-file meeting to hammer out our priorities. Velvette made a flyer explaining the negotiations process and urging dancers to attend. She had hand-drawn little sharks with pointy teeth to represent the lawyers for either side. SEIU had assigned us a professional negotiator, Stephanie Beatty, a longtime labor activist and one of the original founders of Berkeley Women’s Liberation, who was deeply committed to our victory. She came to our meeting, and we asked her what we should put in our contract.

“Totally up to you,” she said. “I can’t tell you how to run your workplace or what rules you should have. You tell me: What conditions would make your lives better?”

We thought about our bottom line (No racial discrimination? Consistent rules for everyone? No surreptitious videotaping?). We thought big (Fully funded health plan including alternative medicine! Retirement! Paid vacation! Tuition assistance! Hot tub in the dressing room!). We brainstormed, dreamed, listed, and prioritized.

We decided to fight hardest for the permanent removal of the hated one-way windows, for an end to racial discrimination in shift assignments, and for fairer policies around attendance and discipline. Of course, management was under no obligation to concede anything to us, so we would need to fight hard for any improvements we proposed.

I’d assumed that as a member of the organizing team, I would be on the contract bargaining crew, but when Stephanie told us that negotiations would likely entail many months of hours-long, weekly meetings, I paused. I’d taken the job at the Lusty in order to work as little as possible so that I could focus on finishing my master’s degree. Yet I’d spent the past months attending secret meetings and stealth-organizing my coworkers to join our union effort, in addition to working onstage in the booth. All this had amounted to a full-time job in itself. I knew I was undermining my own reasons for taking the job in the first place, but it felt too crucial, too exciting to put aside, so I’d stuck with it, telling myself that once we won the election, it would be done. We’d have a two-hour meeting with management and our union reps to hash out a contract, and then it would be over and I could go back to dancing twelve hours a week. So when Stephanie explained that contract negotiations were often longer, more contentious, and more arduous than initial organizing campaigns like the one we’d just completed, I felt torn, once again, between my two selves: the bookish, scholarly graduate student, alone in her library carrel, and the stiletto-shod stripper hollering at her boss about unfair working conditions. While organizing, I felt guilty for neglecting my studies, told myself I was manufacturing drama to avoid my real work: academic writing. But at the library, I found myself worrying about management’s next move, or planning my next pro-union dressing room flyer. I felt I owed my scholar self the time and space to focus on writing my master’s thesis and applying to PhD programs. I knew that my comrade-dancers could and would carry the baton for this leg of the race.

When those comrades—Velvette, Jane, Naomi, Isis, Decadence, and support-staff Scott—did arrive at the bargaining table to negotiate, management simply rejected all our proposals out of hand or quibbled over petty issues. After a few months of this—it was now early 1997—we realized that they were trying to run down the clock. If a year passed, and we hadn’t agreed upon a contract, management could claim a stalemate and petition for union decertification. Not only would we not have a contract, but we would lose our union, and management would almost certainly fire all of us organizers and get us blacklisted around town. We needed to pressure them to come to the table for real, but how? The answer, as was so often the case at the Lusty Lady, was between our legs.

In assembly-line jobs, workers sometimes use a work-to-rule action to pressure management to make changes. This involves all workers agreeing to do the bare minimum required by their contract or job description, which results in a slowdown of production. This hurts profits, but it doesn’t endanger anyone’s job, because technically, everyone is doing what they are obligated to do. Simply dancing more slowly wouldn’t accomplish this in our case, obviously, so we devised a strategy that would.

Normally, our stage performances were quite explicit. We would bend over in front of the windows or face them with one foot up on the windowsill. Sometimes we even put both feet on a windowsill and held ourselves up with the three-foot Lucite bars bolted vertically to the mirrored wall on either side of each window.

While the performance of explicit pussy shows was the unspoken norm at the Lusty, the Performers’ Standards we’d all been handed when we were hired did not state that we were required to perform this explicitly; they only said we needed to: (1) be nude, (2) pay attention to the open windows, (3) perform both up close and far away from those windows, and (4) make eye contact with the customers. So we decided that our slowdown would entail collectively working to this rule—we would be naked, pay attention, move close to and away from the windows, and make eye contact, but nothing else. We would eschew the explicitness of our usual performances in order to frustrate customers, slow down business, and pressure management to negotiate with us.

We publicized the upcoming slowdown openly to dancers, not only to make sure everyone participated, but also to let management know that we were united, willing, and able to hurt their bottom line if they wouldn’t negotiate with us. When the day of the action came, the show directors were watching from their private observation booth, behind their very own one-way glass.

We were prepared for this surveillance and had cautioned dancers not to talk onstage at all, to adhere meticulously to the costume standards—cover tattoos, remove body piercings, wear nothing but shoes to avoid being accused of overcovering, move around the stage, smile, and make eye contact. During our “pink-out” we maintained near complete discipline around these standards so as not to give management an excuse to fire or punish anyone. In fact, when we were motivated by solidarity and our commitment to achieving our collective aim, we were far more attentive to our work standards than we ever were when management was enforcing them with carrot-and-stick measures.

Things seemed to be going well during my first pink-out shift. No one broke ranks to bend over or put their legs on the windowsills, and the stage was silent except for the music and the occasional murmur of “perm” to indicate the end of someone’s shift. But when I walked into the dressing room for my break, I found Summer, a twenty-year-old dancer with a young son at home, talking quietly with Jane, and looking somber.

“Hey, what’s up?” I asked, concerned.

“Collette said I had to have a disciplinary meeting before I can work again.”

“Shit. Did she say why?”

“No, but she saw me dancing without doing any pussy shows, so it’s gotta be about that.”

“She’s allowed to have a union rep in the meeting,” added Jane. “I’m going with her.”

“What time?”

“Meeting’s at 2:00.” It was 1:40.

I went back on stage at 1:49 and quietly, one by one, told the other dancers what was going on downstairs. At 2:15, I heard someone running, fast and loud, down the hall leading to the stage. Jane appeared at the stage entrance and yelled, “THEY JUST FIRED SUMMER!” I heard others running and yelling the news backstage and out in the customer area, where support staff worked.

“Let’s walk out!” I said excitedly. The other dancers moved toward the door, ready to throw down for our girl.

“No!” Jane hissed urgently. “They can definitely fire you for that. Stay here and keep dancing.” She took off back down the hall.

I kicked off my heels and ran to the dressing room, where I used a Sharpie to write on my hands, “Don’t spend $ here! Unfair to labor!” I went back onstage and showed the other dancers, then passed around the Sharpie. We danced around, placing our hands on our tits and asses as we stuck them in the windows, where our message could reach the customers, but not the show directors’ viewing booth or the unblinking closed-circuit camera on the ceiling.

When my shift was over, I dressed quickly and ran outside. A group of dancers and support staff were at the theater entrance, making picket signs that read REHIRE SUMMER and UNFAIR TO LABOR! NEGOTIATE, DON’T RETALIATE. I took a marker and one of the poster boards someone had brought and made a sign: HONK FOR STRIPPERS’ RIGHTS! Throughout the afternoon and into the evening, more dancers showed up for the picket. Because this wasn’t an actual strike, we told those scheduled to work to do their shifts as usual and join us afterward, since they could be fired for not showing up.

The next morning, I biked to the theater at 9:00 A.M. Sorcia, Jane, Octopussy, Amnesia, and Scott were already there, making more signs and laying out those we’d made the day before. As we began our picket, a few more dancers and support staff showed up. Our little demonstration walked, waved our signs, and chanted “Rehire Summer!” Octopussy handed out hot-pink, quarter-sheet flyers explaining our situation and urging customers to boycott the theater and call management to demand that they rehire Summer and negotiate with us in good faith. Some complied, but others skittered past us into the theater for their morning session.

At 9:15, about fifteen people we didn’t know—mostly fortyish African American and Latina women, older and more professionally dressed than our scraggly little group—came walking up Telegraph Hill toward us. One of them was carrying a bullhorn. Uh-oh, I thought. Grown-ups. Were they . . . cops or . . . ? When they reached the theater entrance, I saw that they were carrying bunches of professionally printed picket signs stapled to sticks, reading UNFAIR TO LABOR! SEIU. Without a word, they each took a sign and fell into line with us, walking in a long, thin oval in front of the theater. The woman with the bullhorn listened to our chant “Two-four-six-eight, don’t go here to masturbate!” and without a hint of hesitation, began shouting it through the bullhorn for others to repeat. When that chant grew stale, she switched to the call-and-response format to teach us some picket-line standbys, which we collectively improvised, so that—“Workers’ rights are under attack! Whadda we do? Stand up! Fight back!” became “Strippers rights are under attack! Whadda we do? Get dressed! Fight back!” and “We are the union” became “We are the Ladies! The lusty, lusty Ladies!”

As we walked the line, I asked the woman in front of me, “Are you all from the SEIU office?”

“Oh no! I work at City Hall, in the assessor’s office. SEIU just put the call out last night that some sisters needed backup on a picket line, and I wasn’t working today, so I came out to support you.” Most of these strangers were members of different workplaces that had affiliated with SEIU—city workers, hospital staff members, public transit operators, custodians, and others—but some were members of totally different unions who had gotten calls from the San Francisco Labor Council (an organization of all the unions together) that we needed support, and they came out to provide it.

I was amazed. I hadn’t thought that regular people with real jobs would care, much less come out on their days off to join our picket, for the whole city to see. Yet here were all these other professional city workers, nurses, and bus drivers showing up to help us carry the weight of our struggle. The group grew larger as the morning wore into afternoon. Passersby stopped and took flyers. Crowds gathered and stared.

Around 2:00 P.M., a thin, blond woman about our age, wearing vintage cat-eye glasses and a ’60s polyester shift dress cut off above the knee, bounced up Kearny Street in our direction. She slowed as she saw the commotion, watched for a minute, then approached Jane, stepping into stride with her.

“What’s going on?” the woman asked.

“We’re picketing because they fired one of our coworkers for union activity,” Jane answered.

“Oh shit,” the woman said. “I’m supposed to audition today, but no way I’m gonna cross a picket line! Should I cancel?”

“If they hire you, will you join our union?” asked Decadence, who was walking the picket behind Jane.

“Oh hell, yeah! I heard about it and that’s why I wanna work here!” said Cat-Eyes.

Jane and Decadence looked at each other and nodded. “Then yeah, go ahead and audition. They’re probably trying to hire a bunch of new girls and stack the roster with nonunion members, so it would be great to have a newbie join our side right away!”

Decadence and Jane hustled Cat-Eyes to the theater door, wished her luck, and returned to the picket line. About an hour later, Cat-Eyes walked out through the glass doors smiling big and waving a new-hire packet at Jane and Decadence.

“Did they ask you about the union?” Jane asked.

“Yeah, but I told them I was totally against it!” Cat-Eyes laughed. “They hired me on the spot.”

We all laughed with her. “What’s your stage name gonna be?” Jane asked.

“Honey,” said Cat-Eyes. Then she grabbed a picket sign and joined our line.

Of course the media showed up. Ever since we’d won our union election, newspapers, TV, and radio shows had courted us endlessly, so when word got out that the Lusty Lady dancers were picketing the theater, TV vans screeched up and newscasters in their centaur costumes—business suit on top for the camera, jeans and sneakers on the bottom, out of frame—surrounded us asking for comments. We were, after all, a curious occurrence, not just because of our jobs, but because our organizing defied a decades-long trend of decreasing union membership throughout the US. While the larger union movement labored unsexily against the tide of late capitalist globalization, with formerly unionized jobs going overseas and membership dropping perilously at the end of the twentieth century, the Lusty Ladies served as a perky counternarrative to this story, unlikely standard-bearers for a movement everyone had believed was dying.

When the cameras showed up, some of the dancers donned wigs and sunglasses to protect their privacy, while others ducked out of the demonstration, but with the solidarity of all the nurses, bus drivers, and teachers who had turned out to support us, our picket line stayed strong. Union advisers had told us that we couldn’t physically block the entrance, and our picket line had to keep moving, but we didn’t need to use force. By talking, yelling, and occasionally shaming, we managed to empty the theater completely within a few hours.

Late in the afternoon, Velvette, Tori, Jane, and Amnesia, who’d been working onstage, came out the front door in their street clothes. “They sent us home. They’re closing the live show,” Amnesia announced. With no money coming in, management didn’t want to pay dancers to work, but they were keeping the video booths open to keep revenue coming in.

But it was more than that. They were trying to starve us out, calculating that we’d call off our picket if keeping it up meant losing our paychecks. They knew they could ride out a day or a week without income, but that we couldn’t.

Their tactic backfired; we got angrier than ever. Some dancers scrawled “Locked Out!” on our signs; I called the union office to ask if we were legally entitled to unemployment benefits; then we all went back to picketing. We stayed out front all night, chanting, laughing, carrying signs into the street, posing for photos with tourists, and giving interviews. Some customers hung out and chatted, and two city supervisors stopped by to give fiery speeches encouraging us to stay strong. Fire engines drove slowly past, horns honking and lights flashing, firefighters hanging out the windows cheering us on.

A year before, I’d been relieved and thankful for the help of SEIU alone. But now, it felt like all San Francisco was there with us, and I was overwhelmed with tears of gratitude that all these people, rather than looking down on us because of what we did for a living, were instead willing to celebrate us—not as sex objects or performers on a stage, but as fellow workers whose struggle was their struggle. The very presence of these comrades seemed also to lift us up in defiance of a world that would shame us, to take that shame and throw it back in the faces of those who dared disrespect us.

The next day, we were there again, our numbers even greater now that no one had to work. Late in the morning, Collette came to the front door and asked if a shop steward could come down to the office. Naomi and Decadence went. We waited anxiously, buzzing with excitement, trying to keep up the picket while watching the door for our heroines’ return from battling monsters. After a long time, Naomi and Decadence emerged from the dark of the theater lobby. We stopped picketing and gathered around.

“Summer got her job back!” Decadence announced. “And they want to open the live show again tomorrow if we’ll go back to work. And they’ll be at negotiations next week with new proposals.” We were stunned into silence for a moment. And then a shriek of victory went up from the crowd of dancers. We all grabbed for Summer, who laughed and cried in disbelief and gratitude and allowed herself to be passed around and hugged and smooched. We celebrated there on the sidewalk, heady with our own strength, ordinary girls suddenly endowed with a power we’d never known, invincible.

Management did return to the bargaining table the following week, as promised, and they brought with them a proposal for substantial across-the-board pay increases, and health insurance for support staff working full time. The coming weeks brought agreements on a progressive discipline system to replace the random firings and pay cuts of the past, on scheduling booth shifts without regard to race, on a clearer attendance policy and raise schedule, and on the permanent removal of the hated one-way windows.

The one point on which we couldn’t reach agreement was the status of our union. We wanted an agency shop in which all workers would have to pay their share of the cost of union representation, since we would all benefit from it. This, we felt, would remove the incentive to “ride free”—to get the benefits of membership without paying the cost. We also figured that more dancers would become members if they knew they had to pay their share of the costs anyway. Management wanted an open shop, in which workers who didn’t join our union would get all the benefits without paying the costs. We hated this idea, mostly because we worried that management would hire a slew of anti-union dancers (or bribe them not to join), then start a decertification campaign once they’d established a majority, effectively rendering our whole organizing effort in vain.

When the negotiating team reported that management was refusing to budge, we took a temperature check on our rank-and-file members’ commitment to an agency shop. The result was a decision to stand firm in this demand; management’s efforts to crush our organizing effort had left a nasty scar of distrust on our collective skin, and we feared that without an agency shop we would lose all our hard-won gains. Buoyed by our victory on the picket line and our subsequent wins at the negotiating table, I was confident that management would give in if we just stood firm.

I was in the dressing room when Decadence phoned from negotiations to inform us that management had just come to the table with something called a “last, best, and final” offer that included an open shop clause. Our team was in a caucus, deciding how to proceed, so Decadence was calling to inform us of the development and get input from those of us who were at work.

“Well, just tell them no!” I answered, foolishly confident. “We all decided that this is too important to concede.”

“No, it’s not that simple,” Decadence explained. “Stephanie says that if we don’t take it, then negotiations are over. Here, you explain it.”

Jane’s voice came on the line: “It’s called a ‘last, best, and final’ offer. She explained that this meant it was the best they were willing to do, their bottom line. Now we need to decide if we are willing to take it, or if we would rather strike.”

“Okay,” I said. “So we strike.”

“Stephanie says if we strike, they might cave in and agree to an agency shop, but if they refuse and we can’t afford to stay out, we could lose all the gains they’ve agreed to.”

“They don’t have to stand by that stuff?”

“No. All those agreements are contingent on getting a whole contract.”

“So we could strike and get everything, or we could strike and lose everything.”

“Yeah.”

Amnesia had come to the dressing room from the stage and was looking at me quizzically. My shift was about to begin, so I handed her the phone, saying, “Here, it’s Jane. She can explain what’s going on.” I slipped on my new neon-green platforms and made my way to the stage, where I danced like a ghost, preoccupied with the heavy burden of this decision. I no longer felt invincible and cavalier about urging the others to strike. Now the choice seemed much more perilous. I knew that I could ride out a strike; I had my teaching job, and RJ was making good money in her job in the finance department of a local museum. But dancers like Summer—a twenty-one-year-old single mother of a three-year-old—and Jasmine—just eighteen but supporting her little brother and sister alone—wouldn’t be able to live without a paycheck for very long. Most of the dancers would need to get other jobs, and then we wouldn’t be able to sustain a picket line.

Management could easily replace us with new dancers, and without a strong picket line to scare off scabs and drive away customers, business would be just fine. Striking would risk everything we had gained, including our union itself. I was willing to take that risk on my own behalf, but I wasn’t willing to urge it on others who would be hurt far worse by the consequences. Still, an open shop would surely invite union busting.

While I was dancing absently and mulling all this over, our negotiators were at work, and when I got to the dressing room for my second break, Jane called again. “We came up with a compromise. It’s called ‘maintenance of membership.’ They’ll let us meet with every new worker when she’s hired so we can ask her to join the union. If she joins, she has to pay dues and remain a member for the duration of the contract.”

“Should we take it?” I asked.

“We’re still deciding,” Jane said.

After my shift, I biked to the lawyers’ offices where negotiations were happening. The team was deep in discussion. Stephanie, our negotiator, encouraged us to think of the contract as a starting point: “This is just your first contract,” she said. “Once you’ve got it in place, you can build on it with each negotiation.”

I hadn’t thought about it in this way before; I hadn’t thought beyond the first contract at all, so consuming had our struggle been. I hadn’t considered that our union would continue into the future, that other dancers would carry on our struggle, that we needn’t right all wrongs in this one moment. Stephanie’s long view was a relief. The team decided to sign the tentative agreement, then hold a ratification vote to make sure the rank-and-file members were on board.

On April 4, 1997, just a few weeks after our first picket, I took my turn sitting in Café Prague with a glittery cardboard ballot box (this election was less formal than the NLRB election certifying our union). Dozens of dancers filed in and out to cast their votes on the contract. At the end of the day, Sorcia counted the votes while the rest of us looked on anxiously. “Sixty-seven yeses, and two nos,” she announced. We had ratified our first union contract. It eliminated the one-way windows permanently, ended racial classification of workers, provided health benefits to support staff, and raised dancers’ wages. The contract we built would seem substandard to most workers in mainstream jobs—dancers weren’t getting health benefits, paid vacation, paid sick days, or a retirement fund—but it was a start.

And, despite the modesty of our gains, this was one of my proudest moments. I’d begun with a narrow goal—to get redress for a simple grievance—but as I’d reached out to others and they’d reached out to me, we’d gradually broadened our sights to issues that extended beyond the peep-show walls—issues like racism, bodily privacy, and our very right to organize and advocate on our own behalf. Along the way, I’d sought out the history that had led to our struggle and had come to see our work in relation to that history—the unionists of the burlesque era, the courageous French prostitutes of the 1970s who claimed asylum in a church, the tireless activists of COYOTE, and, yes, the miners and farmworkers who’d faced violence to stand up for their rights, even the nurses and clerks who had walked our picket line and called us sisters. I felt proud to be carrying their work into the future.

As I finished my master’s degree and started working on my PhD, dancing on and off, workers at other clubs in town and even around the country heard about our successful union campaign and started to organize. I was out for burritos with Isis in the Mission one day, discussing which of the four butches she was dating was the best girlfriend material, when she mentioned that she had gotten hired at the only other peep show in town, the Regal.

“Why?” I asked, knowing that in addition to her job at the Lusty, she had family money, plus on-and-off work as a professional dominant.

She looked around and lowered her voice. “Don’t tell anybody, but Velvette, Jane, and I all got jobs there over the past few weeks. We’re going to organize it!”

A week later, I was riding my bike down Market Street on my way to the theater. As I passed the lap-dance clubs—the Crazy Horse, Market Street Cinema, Chez Paree, and the New Century—I noticed that the neon sign at the Regal was dark. I slowed my bike to a stop in front of the marquee. The doors were closed. No bouncers stood at the entrance, and no dancers smoked on their breaks in front of the sign that read THE REGAL: WHERE YOU ARE KING!

“What happened?” I asked Isis when I got to the dressing room at the Lusty.

“The boss found out we were organizing,” she told me. “He shut it down. I went in for my shift Tuesday and it was just closed. No notice, no pink slip, nothing.”

“Jesus.”

“Tell me about it,” said a tall, Deborah Harry look-alike with tattoo sleeves, piercings that jutted from the left and right sides of her lower lip like little silver fangs, and shoulder-length platinum hair that she wore with roots showing unabashedly.

“Polly, this is Pepper,” Isis told me, “an organizer from the Regal. She’s a Lusty now.”

“Lucky you,” I snorted.

“Lucky you!” she snorted back, and I laughed. “Actually, though, it kinda sucked to have my place of employment close with zero notice,” Pepper continued. “I thought we were gonna be able to at least force an NLRB election. Fucking union busters.”

“So they just shut it down for good?”

“Yup,” Pepper answered, turning to the mirror to apply makeup. “That rat bastard owns clubs all over this fuckin’ town. He’ll just open a new place down the street.”

With the Regal closed, the Lusty was the only peep-show-style theater left in town; the ten or so other clubs were full-contact lap-dance clubs. Our unionization drive had created a lot of buzz about the Lusty, so business was good. With the one-way windows gone, and the threat of secret videotaping all but eliminated, I no longer felt anxious and paranoid onstage. Once again, I could dance with abandon, even more so now that my hair had grown out and I’d discarded my wig. My hourly wage had gone up to $27 with the new contract, and my booth shifts were yielding more now too. With three years under my garter belt, and as a founding member of the union, I was now considered an old-timer at the Lusty, a status I was enjoying.

Then, in the spring of 1998, I got a call from Amnesia.

“Hey, Ava!” I said, using her real name. “How you doing?”

“Hi, sweetie. I’m okay, but I have some bad news.”

“Oh, no, what?” I asked, not too worried.

“You know how Stephanie [Violet/Honeysuckle’s real name] went down to Arizona last week to work baseball spring training?”

“Yeah?” Honeysuckle financed her travels to different cities and countries by dancing or turning tricks while she was on the road. Places where groups of well-paid men gathered—such as professional baseball’s spring training season in the Southwest—were prime hunting grounds. But why was Ava calling to tell me this? I felt uneasy, waiting for that other shoe to drop.

“She and a friend were driving to one of the games, and there was an accident.”

“Oh god. Is she in the hospital? Is she hurt badly?”

“Honey, she didn’t make it.”

I thought of Stephanie in her Violet wig, bouncing Sybil on her lap in the dressing room, joking about Sensual John, about pushing her through the crowds at last year’s Gay Pride Parade on her roller skates, about her sitting at our poker table eating popcorn, inventing a five-card-stud variation she called Polk Street, after San Francisco’s gay hustling strip: “Queens are wild, and one-eyed Jacks are trade! That means they’re wild only in the presence of a queen!”

RJ and I went to Honeysuckle’s memorial at Edinburg Castle, a bar near her apartment. Lusties convened at the top of nearby Nob Hill dressed in flamboyant mourning costumes to honor our girl’s famously dramatic style. Decadence led the procession in full Victorian widow’s weeds, yards of gossamer black lace covering her face and floating behind her. Outside the bar, a bagpiper played a miserable dirge as we filed in.

When a particularly legendary athlete retires, his professional sports team will sometimes retire that player’s number as a gesture of honor. After Stephanie died, one or two more Violets were christened at the Lusty, but no Honeysuckle ever danced that stage again. For me, her death marked the end of the ’90s, an epoch she embodied so perfectly, with her polyamory, her grungy-but-shiny club kid aesthetic, her passion for life on the margins. My initial, distant awe of her delicate beauty, so at odds with her fearless sexuality and brash, geeky manner, had morphed into love for my peep-show mentor, who’d schooled me on lip liner, hustling, and Sensual John. Looking around the bar at the other mourners, I realized that over the course of the now three years I’d been working at the Lusty, I’d grown to love many of these women. The late-night shifts, the secret meetings at Tori and Velvette’s, the scouting mission to the EDA meeting at the union office, the election, the picket line chanting, and now the sudden death of one of our own—these had all bonded me to these beautiful, brave girls as I never expected when I’d first walked past that neon dancing lady into the dark little hole that now seemed to feel like a home.