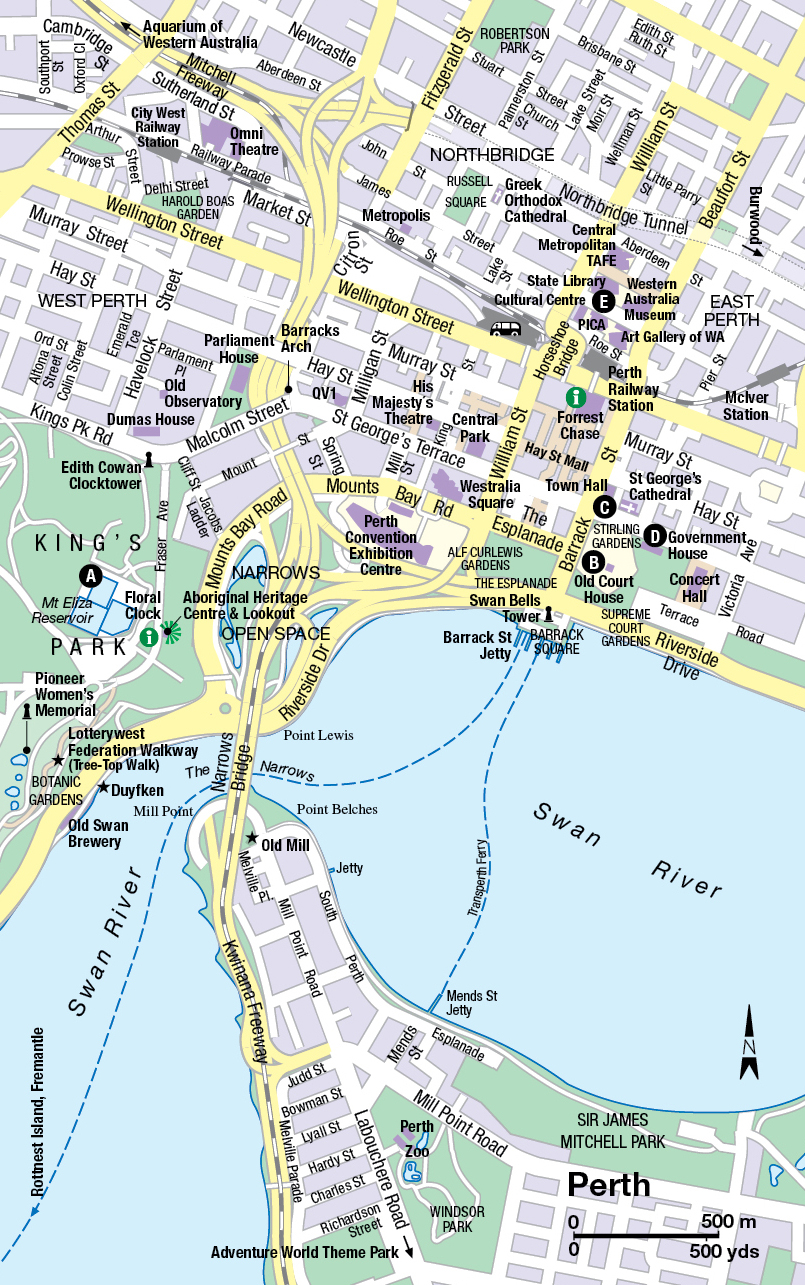

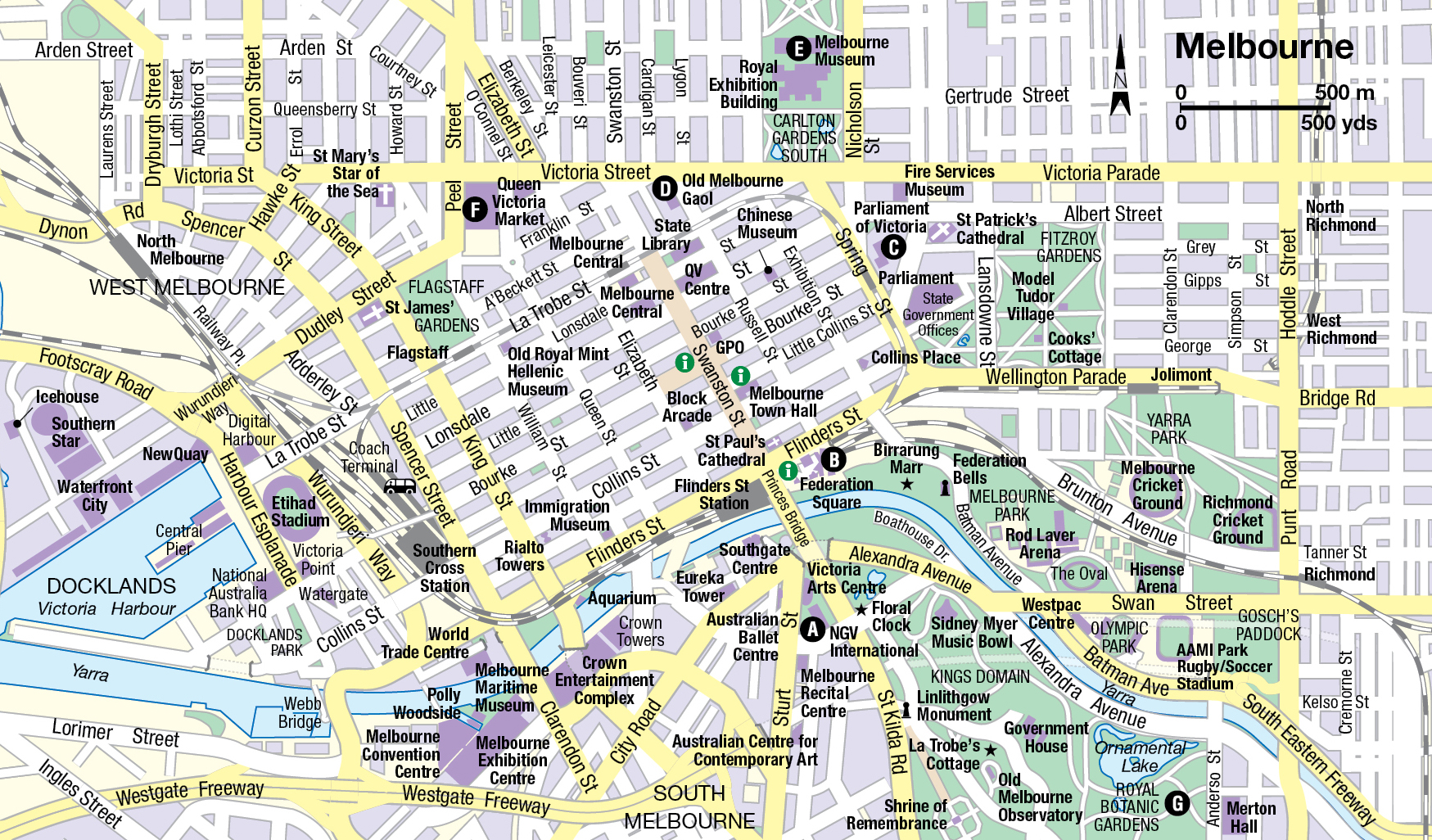

Deciding where to go and what to see in Australia may be the hardest part of the journey. How can you squeeze so much into a limited time? Where do you go in such a vast country?

About 54 million passengers a year fly Australia’s domestic airline routes. Budget airlines make flying from city to city an affordable option, although it’s best to plan ahead to get the best fares and flight times. Alternatives are slower, but often more revealing. Try the transcontinental trains and the long-distance buses, some of which are equipped for luxury travel.

Since you probably can’t see all of it, you’ll have to arrange your tour of Australia to concentrate on seeing a manageable slice or two of the continent. Planning any itinerary requires compromise, depending on the time and funds you have available, the season, your special interests and your choice of gateway city. Sydney is the main gateway into Australia, but some airlines allow you to arrive in Cairns, for example, and depart from Sydney or Perth.

This section of the guide is arranged according to the geography of Australia’s states. Although there is no visible difference between the red deserts of the Northern Territory and those of South Australia, it’s practical to consider them in the context of the political frontiers. Besides, the way that history and chance carved Australia into states comes close to providing a fairly natural division into sightseeing regions.

In each state or territory we start with the capital city gateway and fan out from there. We begin where European settlement of Australia began, at Sydney Cove. After a side trip to the federal capital, Canberra, we continue beyond New South Wales, in an anti-clockwise circuit from Queensland to Victoria, ending with a look at the continent’s lovely green footnote, Tasmania.

NEW SOUTH WALES

Sydney can’t help but dominate New South Wales (NSW), if only because most of the state’s population lives in the capital. However, beyond the metropolis, the state – six times the size of England – is a varied patchwork of terrain, lurching from dairyland and desert to vineyards and craggy mountains.

Sydney, with the famous Opera House in the foreground

Hamilton Lund/Tourism NSW

Sydney 1 [map] is Australia’s oldest, liveliest and biggest city (total population 4.6 million). If the world had a lifestyle capital, Sydney would be a strong contender –ironic considering it began life as a British penal colony. Sydney is sun-drenched, brawny, energetic, fun loving and outdoor obsessed. The city ranks well on international lists of favourite tourist destinations; its residents know this and they revel in it. After hours – and Sydneysiders do live for the after hours – Sydney offers every imaginable cosmopolitan delight. It’s a sunny coincidence that beaches famous for surfing and scenery are only minutes away.

Sydney Harbour has been stealing the show ever since the first convicts arrived in 1788. For a quick appreciation of the intricacies of Port Jackson (the official name for Sydney Harbour), gaze out from the top of Sydney Tower, Sydney’s tallest building. From here you can see the clear blue tentacles of water stretching from the South Pacific into the heart of the city. Schools of sailing boats patrol the harbour, shattering the reflection of skyscrapers, the classic Sydney Harbour Bridge and the iconic opera house. It’s a pity that James Cook never noticed this glorious setting as he sailed right past on his way home to England from Botany Bay. Sydney Harbour National Park fringes a long, leafy stretch of the northern side of the harbour and also includes some harbour islands and a chunk of the southern foreshore. For information about harbour sights, click here. Exploring Sydney Harbour is as easy as jumping on a commuter ferry or taking a sightseeing tour. Most tours – by land or sea – leave from Circular Quay.

Most of the world’s great cities have a famous landmark that serves as an instantly recognisable symbol. Sydney has two: the perfect steel arch of Sydney Harbour Bridge and the billowing shell-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House. That’s what happens when engineers and architects embellish a harbour coveted by artists as well as admirals.

The cream ‘sails’ of the Opera House gleam in the sun

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Sydney Opera House

There’s a real sense of occasion and style about the structure of the Sydney Opera House A [map] (www.sydneyoperahouse.com; guided one-hour tours daily, every half-hour 9am–5pm), both inside and out. This unique building, covered in a million tiles, has achieved the seemingly impossible by improving a virtually perfect harbour. Yet its controversial architect left the country in a huff at an early stage of the building’s construction.

Pre-opera house, the promontory was the location of a tram depot, but in the 1950s the government of New South Wales decided to build a performing arts centre on the site. In 1957, a Danish architect called Jørn Utzon won an international competition to design the building. His novel plan included problems of spherical geometry so tricky that he actually chopped up a wooden sphere to prove it could be done. The shell of the complex was almost complete when Utzon walked out in 1966 due to pressure from the state government; the interior, which was in dispute, became the work of a committee. Despite this, from the tip of its highest roof (67 metres/220ft above sea level) to the Drama Theatre’s orchestra pit (more than a fathom below sea level), this place oozes grace, taste and class.

In 2002, Utzon was awarded the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s version of the Nobel Prize, and in 2004 a room in the Opera House was named after him, complete with a 14-metre long, floor-to-ceiling woollen tapestry designed by the architect installed inside. But Utzon never returned to Sydney; he died in 2008 without ever laying eyes on his finished masterpiece.

Sailing through the Harbour

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Circular Quay

Although cruise ships and water taxis also dock here at Circular Quay B [map] (short for Semi-Circular Quay, as it was more accurately originally named), most of the action involves ferries, which sail to various destinations including the zoo (for more information, click here) and seaside suburbs such as Manly (for more information, click here). The quay’s high-paced flow of human traffic includes hasty travellers, leisurely sightseers, street musicians, artists, hawkers and people just ‘hanging out’. Whether you see Australia’s busiest harbour from the deck of a luxury liner, a sightseeing boat, or a humble ferry, don’t miss experiencing this invigorating angle on the city’s skyline.

Susannah Place is an example of a working-class terrace

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Rocks

To see where it all began, stroll through the charming streets of The Rocks C [map] (www.therocks.com), just west of Circular Quay. You can take a 90-minute guided walking tour (tel: 02-9247 6678 to book) or conduct your own tour. Here modern Australia’s founding fathers – mostly convicts who had been charged with anything from shoplifting to major forgery – came ashore in 1788 to build the colony of New South Wales. This historic waterfront district has everything a traveller could want: lovely views at long and short range, moody old buildings, cheerful plazas and plenty of distractions in the way of shopping, eating and drinking. There are plenty of tourists too.

But it nearly was not so. The Rocks was once one of Sydney’s most squalid and dangerous quarters, a Dickensian warren of warehouses, grog shops and brothels, where the rum was laced with tobacco juice and the larrikin ‘razor gangs’ preyed on the unwary. An outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900 was another low-light in The Rocks’ sordid history.

The whole area was due to be levelled for redevelopment in the 1970s, but there was fierce resistance from residents and academics, and the project was thwarted when the construction unions, led by activist Jack Mundey, refused to start work. This was the beginning of the Green movement to preserve the antiquities and atmospheric elements of Old Sydney.

A wide range of local leaflets and maps is on offer at the Sydney Visitor Centre (corner Argyle and Playfair streets; www.shfa.nsw.gov.au; daily 9.30am–5.30pm). You can book tours there as well.

Nearby, Cadman’s Cottage is central Sydney’s oldest (1816) surviving house – a simple stone cottage occupied for many years by the government’s official boatsman. It’s now the information centre for Sydney Harbour National Park. Not far away, the Museum of Contemporary Art (www.mca.com.au; daily 10am–5pm; free) gives new life to an Art Deco building. The museum’s collection ranges from Aboriginal bark paintings to the latest – and strangest – installation works. There are also plenty of touring exhibitions. The café on the terrace (with harbour view) is excellent.

The Museum of Contemporary Art

Dreamstime

Just south of The Rocks, on Bridge Street on the site of the first Government House, the fascinating Museum of Sydney (daily 9.30am–5pm; charge) promises to take visitors on ‘a journey of discovery’ from 1788 to the present day.

North of Cadman’s Cottage are solid 19th-century bond stores, now converted to offices and shops such as Campbell’s Storehouse (which sells food, souvenirs, arts and crafts). Heading west from Cadman’s Cottage you’ll arrive at the similar Argyle Stores. Beyond is the Argyle Cut, a massive gap through the sandstone cliffs that was initially hacked out by convict labour-gangs using pickaxes.

At the top of Argyle Cut, Cumberland Street provides pedestrian access to Sydney Harbour Bridge via a set of steps. An unusual vantage point for viewing the bridge, the harbour and the skyline – from the top of one of the bridge’s massive pylons – can be accessed here. The Pylon Lookout (www.pylonlookout.com.au; daily 10am–5pm; charge) is in the southeast tower, which also contains a museum.

Not far away, the Australian Hotel, a friendly pub in the older Aussie tradition, stocks beers from every state in the country. It is one of only two pubs in Sydney to serve Bavarian-style unfiltered beers created by brewer Geoff Scharer, acclaimed as the best in Australia.

Pulling pints at the Lord Nelson Hotel

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Rocks Market

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

A little further on, in Argyle Place, you will find a neat row of terraced houses straight out of Georgian England. Two other old pubs in this area deserve mention. The first, the quaint Hero of Waterloo at 81 Lower Fort Street, was built in 1843 on top of a maze of subterranean cellars through which drunken patrons were conveyed to be sold as crew to unscrupulous sea captains; that practice has died out but the cellars remain. The second, the Lord Nelson Brewery Hotel, a square sandstone block of a building at the corner of Kent and Argyle Street, was built around 1840 and has maintained something of a British naval atmosphere ever since. It brews its own beers, some of them pretty potent.

For history without the refreshments, visit the sandstone Garrison Church, officially named the Holy Trinity Anglican Church, which dates from the early 1840s. As the unofficial name indicates, it was the church for members of the garrison regiment, the men in charge of the convict colony. It’s now a fashionable place to get married.

At the start of George Street, close to the Irish-influenced Mercantile Hotel, The Rocks Market (Sat–Sun 10am–5pm) takes place every weekend under a 150-metre (492-ft) long canopy. Street entertainers perform, while stall-holders sell crafts, souvenirs, toys and gifts. Nearby, Customs Officers Stairs lead down to some charming harbour-side restaurants housed in old bond stores, fronting Campbells Cove. Just across the harbour is the Opera House.

Overhanging The Rocks, Observatory Park is a perfect place from which to gaze at the sky or at Sydney Harbour. Observatory Hill here is the highest point in the city, visible for kilometres around. Since the middle of the 19th century, every day at 1pm precisely, a ball is dropped from the top of a mast to enable sea captains to check their chronometers. Sydney Observatory (www.sydneyobservatory.com.au; daily 10am–5pm) is now a museum of astronomy, and opens every evening (times vary according to season) for talks, films and star-gazing (bookings, tel: 02-9921 3485).

Another favourite lookout is Dawes Point Park, where a scattering of old cannons provides the perfect perch for watching the ferries and sailing boats.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Here, you’re in the shadow of the Sydney Harbour Bridge D [map], with its drive-through stone pylons (purely ornamental) and colossal steel arch. The bridge stars on television each New Year’s Eve, when it serves as a platform for a spectacular fireworks display to bid farewell to the old year and welcome in the new. Pyrotechnics are fired from the arch and more fireworks on the road-span create a Niagara-like cascade into Sydney Harbour.

Linking the city and the north, the bridge’s single arch is 503 metres (1,650ft) across – wide enough to carry eight lanes of cars and two railway tracks, as well as lanes for pedestrians and cyclists. When it was built, during the Great Depression, Sydneysiders called the bridge the Iron Lung, because it kept a lot of people ‘breathing’ – by giving them jobs. It takes 10 years to repaint the steel-grey bridge, at the end of which it’s time to start again. To ease traffic congestion a tunnel has also been built under the harbour.

Pipped at the post

In 1932, at the opening ceremony of the Harbour Bridge, an Irish-born member of a proto-fascist group, Francis Edward de Groot, rode up on a horse and sliced through the ribbon with a sword before the left-wing premier of NSW, Jack Lang, could cut it.

A company called BridgeClimb (tel: 02-8274 7777; www.bridgeclimb.com.au; charge) conducts guided walks for small groups over the bridge’s massive arches. Not across the walkway below, but over the arches above. For decades, groups of daredevils had been doing this illicitly. Since the legal climb began in 1998 the waiting list has grown quite long and it pays to book your climb as far in advance as you can. You can even do the climb at dawn, twilight or at night, though excursions are understandably postponed during electrical storms. It’s not a cheap thrill: tickets start from A$198, and cost more for twilight or dawn climbs or at weekends (minimum age 10).

City Centre

A similar tour operates from the top of Sydney Tower E [map] (Centrepoint, corner of Pitt and Market streets; tel: 02-9222 9491; www.sydneytowereye.com.au; daily 9am–10.30pm, till 11.30pm Sat; charge). Skywalk offers walks outside the tower’s turret, the city’s highest vantage point, at 305 metres (1,001ft) above the street. Those without a head for heights can still take in the view; in the lifts it takes only 40 seconds to reach the observation decks, where amateur photographers get that glazed look as they peer through the tinted windows to unlimited horizons. On a flawless day you can see all the way north to Terrigal and south to Wollongong, far out to sea to the east, and as far west as the Blue Mountains. Otherwise, look down at the seething shopping streets around the tower. Pedestrians-only Pitt Street Mall is one of the city’s main retail centres, home to department stores and shops of all kinds. The Strand Arcade, which runs off the Mall, is a grand old shopping arcade full of upmarket boutiques.

A short distance towards the harbour is the city’s main square, Martin Place, flanked by the imposing Victorian General Post Office (GPO) building. This has been imaginatively converted into a stylish modern complex including a five-star hotel.

The ornate Queen Victoria Building

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

From the same era, but even grander, the sandstone Queen Victoria Building F [map] (www.qvb.com.au; Mon–Sat 9am–6pm, Thur 9am–9pm, Sun 11am–5pm) occupies a whole block on George Street opposite the Town Hall. The Byzantine-style ‘QVB’ began as a municipal market and commercial centre, including a hotel and a concert hall, topped by statues and some 21 domes.

Built in 1898 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, it was faithfully restored in the 1980s to create a magnificent all-weather shopping centre housing nearly 200 chic boutiques, cafés and restaurants, in a cool and unhurried atmosphere of period charm. Pierre Cardin called it ‘the most beautiful shopping centre in the world’. The Galeries (www.thegaleries.com), across George Street, offer yet more shopping opportunities in a modern space.

Next door to the QVB, Sydney’s Town Hall (www.sydneytownhall.com.au; daily 9am–5pm) enlivens a site that used to be a cemetery. The Victorian-era building, home of the city council, is also used for concerts and exhibitions. The Anglican St Andrew’s Cathedral next to it dates from 1868.

Performers in Chinatown

Hamilton Lund/Tourism NSW

Chinatown and Darling Harbour

After dark, young Sydneysiders flock to the section of George Street heading south from the Town Hall, lined with video entertainment arcades, fast-food joints and a cinema complex. Sydney’s fledgling Spanish Quarter begins nearby on the corner of George Street and Liverpool Street – there’s a choice of tapas bars here.

In the adjacent Chinatown district, gourmets can enjoy the delights of Peking, Cantonese and Szechuan cuisine. The substantial local Chinese community is joined here by Sydneysiders and tourists enjoying the Chinese cafés, restaurants and shops selling exotic spices and knick-knacks. The district’s centrepiece is Dixon Street, a pedestrian zone framed by ceremonial gates.

If you’re in the area at the right time, check out Paddy’s Market in Hay Street (Wed–Sun 9am–5pm), a brick building beneath a skyscraper called Market City. Paddy’s is full of stalls selling almost anything from seashells and sunglasses to fruit and vegetables. Market City has plenty of Chinese and other Asian eateries to satisfy hunger pangs.

Nearby, the modern leisure precinct of Darling Harbour is well stocked with shops, restaurants and attractions, and a light rail system links it to more central areas. On the city side of Darling Harbour lie Cockle Bay Wharf and King Street Wharf, complexes of bars and restaurants. These areas have proved much more popular than the shopping and dining complex overlooking the harbour on the western side, mainly because they are easier to reach on foot from downtown Sydney.

Kids love Sydney Aquarium

Dreamstime

Not far away, Sea Life Sydney Aquarium G [map] (www.sydneyaquarium.com.au; daily 9am–8pm; charge), relaunched as a Sea Life Centre in 2012 after a A$10 million refurbishment, is one of the largest aquariums in the world. In its oceanarium, large sharks weigh up to 300kg (660lb) and measure over 3.5 metres (11ft) long. The Great Barrier Reef Complex is home to hundreds of colourful species, and a visit there is the closest thing to diving on the actual reef. The adjacent Sydney Wildlife World (www.sydneywildlifeworld.com.au; daily 9am–5pm; charge) is a mini-zoo showcasing a selection of native fauna, from lizards and snakes to parrots and wallabies. The star attractions, however, are the koalas, which, for an extra fee, you can have your photo taken with.

Other nearby attractions include the Australian National Maritime Museum (www.anmm.gov.au; daily 9.30am–5pm, till 6pm in Jan; charge), a Chinese garden (daily 9.30am–5pm), an IMAX cinema, and the Sydney Entertainment Centre (www.sydentcent.com.au), which is used for concerts. Beyond the Maritime Museum, in Pyrmont, is Star City Casino (daily 24 hours).

Hyde Park

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Parks and Gardens

Although Sydney’s lush Hyde Park is only a fraction the size of its namesake in London, it still provides the same sort of green relief. Like most big-city parks, however, it should be avoided after sunset. The most formal feature of the semi-formal gardens, the Anzac War Memorial, commemorates the World War I fighters in monumental Art Deco style, with later acknowledgments to World War II soldiers.

Sightseers interested in old churches should mark a few targets on the edge of Hyde Park. To the north, the early colonial St James’ Church in Queens Square was the work of the convict architect Francis Greenway. Just across College Street on the east is the Catholic St Mary’s Cathedral.

You can view the cathedral’s spires while immersed in a swimming pool next door at Cook + Phillip Park Aquatic and Fitness Centre (www.cookandphillip.org.au; Mon–Fri 6am–10pm, Sat–Sun and public holidays 7am–8pm; charge). You can’t readily see the complex from the street, yet when you’re inside, its huge windows offer amazing views and let in lots of light. There are three pools – one with a wave machine. There’s a café inside, or, if you want to eat alfresco, Bodhi’s vegan restaurant does good business just outside.

The ornate Great Synagogue (tours Tue and Thur at noon) faces the park across Elizabeth Street. Jews have lived in Sydney since the arrival of the first shipment of prisoners.

The Australian Museum H [map] (tel: 02-9320 6000; http://australianmuseum.net.au/; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge) on College Street specialises in natural history and anthropology, and has lots of activities and events suitable for inquisitive minds. Highlights include a dinosaur gallery (complete with life-size models and 10 complete skeletons), an exhibit of Australia’s megafauna (giant-sized marsupials and flightless birds), a hands-on plant and animal identification centre, a gallery devoted to Australia’s unique ecosystems, the Indigenous Australians exhibition, and a human evolution gallery.

Hyde Park Barracks (http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge), designed by Greenway and located between Hyde Park and the Botanic Gardens, is now a museum of social history. On the top floor, one large room features a reconstruction of the dormitory life of the prisoners who once slept there. Next door, the Mint (10 Macquarie St; tel: 02-8239 2288; http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au; daily 9am–5pm; free) processed gold-rush bullion in the mid-19th century.

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Another large park adjacent to Hyde Park is called the Domain, where concerts are held in summer. On one side of the Domain is the Art Gallery of New South Wales I [map] (www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au; daily 10am–5pm; free, charge for exhibitions) consisting of a formal exterior decorated with much bronze statuary and a modern extension that infuses light into the building and provides sweeping views of east Sydney, part of the harbour, and the suburb of Woolloomooloo. An afternoon at the art gallery will give you a crash course in more than a century of traditional and modern Australian art. The Yiribana Gallery is devoted to Aboriginal art and Torres Islander art (guided tours daily 1pm; free).

The Royal Botanic Gardens J [map] (www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au; daily 7am–sunset; free guided walks daily at 10.30am) began as a different sort of garden; here the early colonists tried – with very limited success – to grow vegetables. Only a few steps from the busy skyscraper-world of downtown Sydney, you can relax in the shade of Moreton Bay fig trees, palms or mahoganies, or enter the Sydney Tropical Centre (daily 10am–4pm; charge), two glass pyramids full of orchids and other tropical beauties. Near the Tropical Centre, overlooking the duck pond, is a café-restaurant where you can relax in peaceful surroundings.

There are several entrances to the gardens and many paths; the most popular entrance is by the Opera House. From here the gardens curve down around Farm Cove to a peninsula called Mrs Macquarie’s Chair. The lady thus immortalised, the wife of the go-ahead governor, used to admire the view from here. Nearby is the venue for the summer season of outdoor films that are shown here during the Sydney Festival (www.sydneyfestival.org.au) and during the St George OpenAir Cinema season (www.stgeorgeopenair.com.au). There’s a lot to see in the Gardens, and if you’re feeling tired, you can take advantage of the hop-on hop-off Trackless Train, which does a 20-minute loop between the Opera House Gate and the Woolloomooloo Gate near the Art Gallery.

Centennial Park, most easily reached from the eastern end of Oxford Street in the inner-city suburb of Paddington, has provided greenery and fresh air to city folk since 1888, when it was dedicated – on the centenary of Australia’s foundation – to ‘the enjoyment of the people of New South Wales forever’. The park’s 220 hectares (544 acres) of trees, lawns, duck ponds, rose gardens and bridle-paths are visited by about 3 million people a year, who cycle, roller-blade, walk dogs, feed birds, play sports, fly kites, picnic and barbecue.

If you fancy a ride on the bridle path, horse rental can be arranged from Moore Park Stables (tel: 02-9360 8747; www.mooreparkstables.com.au). Bicycles and pedal-carts can be hired from Centennial Park Cycles (tel: 02-9398 5027; www.cyclehire.com.au). Centennial Park Kiosk is a lovely setting for a meal and a glass of wine. Beside it stands a charming, if curious, modern stone fountain.

The Belvedere Amphitheatre here provides an outdoor venue for events and productions. In summer, a popular Moonlight Cinema programme (tel: 1300 551 908; www.moonlight.com.au) is held there. Films start at about 8.30pm, and tickets are available in advance from the website or at the gate from 7pm.

Elizabeth Bay House

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Kings Cross and Paddington

East of the Domain is the district of Woolloomooloo – a wonderful word, the origins of which cause some debate, but either mean ‘place of plenty’ or refer to a young black kangaroo. Woolloomooloo was threatened by demolition in the 1970s, but was saved by resident protests and union ‘green bans’.

East of Woolloomooloo, bright lights and shady characters exist side by side in Kings Cross, just one railway stop from Martin Place. ‘The Cross’, is Sydney’s version of Pigalle, in Paris, or London’s Soho – neon-filled, a bit tacky but rather fun, crawling with hedonists of all persuasions. Action continues 24 hours a day, with a diverting cavalcade of humanity – the brightly coloured, the bizarre, the stoned, the happy and the drunk. On weekends, tourists flock to The Cross to glimpse a bit of weirdness. Sometimes though, the weirdest characters they spot are other tourists.

The main drag here is Darlinghurst Road, bohemian verging on sleazy and dotted with strip joints, fast-food outlets, tattoo parlours and X-rated book and video shops, backpacker hostels and cheap hotels. Gentrification is progressing rapidly, however, and several stylish bars, restaurants and hotels have opened. The neighbouring area of Potts Point offers good eating – try Fratelli Paradiso just off Macleay Street.

A five-minute walk (and a world away) from Kings Cross Station brings you to Elizabeth Bay House (www.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au; Fri–Sun 9.30am–4pm), a superb example of colonial architecture, built in 1835 and nestled in the posh enclave of Elizabeth Bay.

Paddington Markets

Pierre Toussaint/Tourism NSW

To the southeast of Kings Cross is Paddington, where the bohemian atmosphere and intricate wrought-ironwork (known as Sydney Lace) on the balconies of 19th-century terraced houses, remind many of New Orleans. After decades of dilapidation, it’s now a fashionable, artsy place to live and one of Sydney’s most sought-after suburbs, with house prices to match. ‘Paddo’, as the locals call it, offers plenty of good restaurants, antiques shops, art galleries, bookshops and trendy boutiques. One of the best markets in Sydney, Paddington Markets (www.paddingtonmarkets.com.au; Sat 10am–4pm) is held in the grounds of Paddington Uniting Church, 395 Oxford Street. It offers art and crafts and is enlivened by a variety of street entertainers.

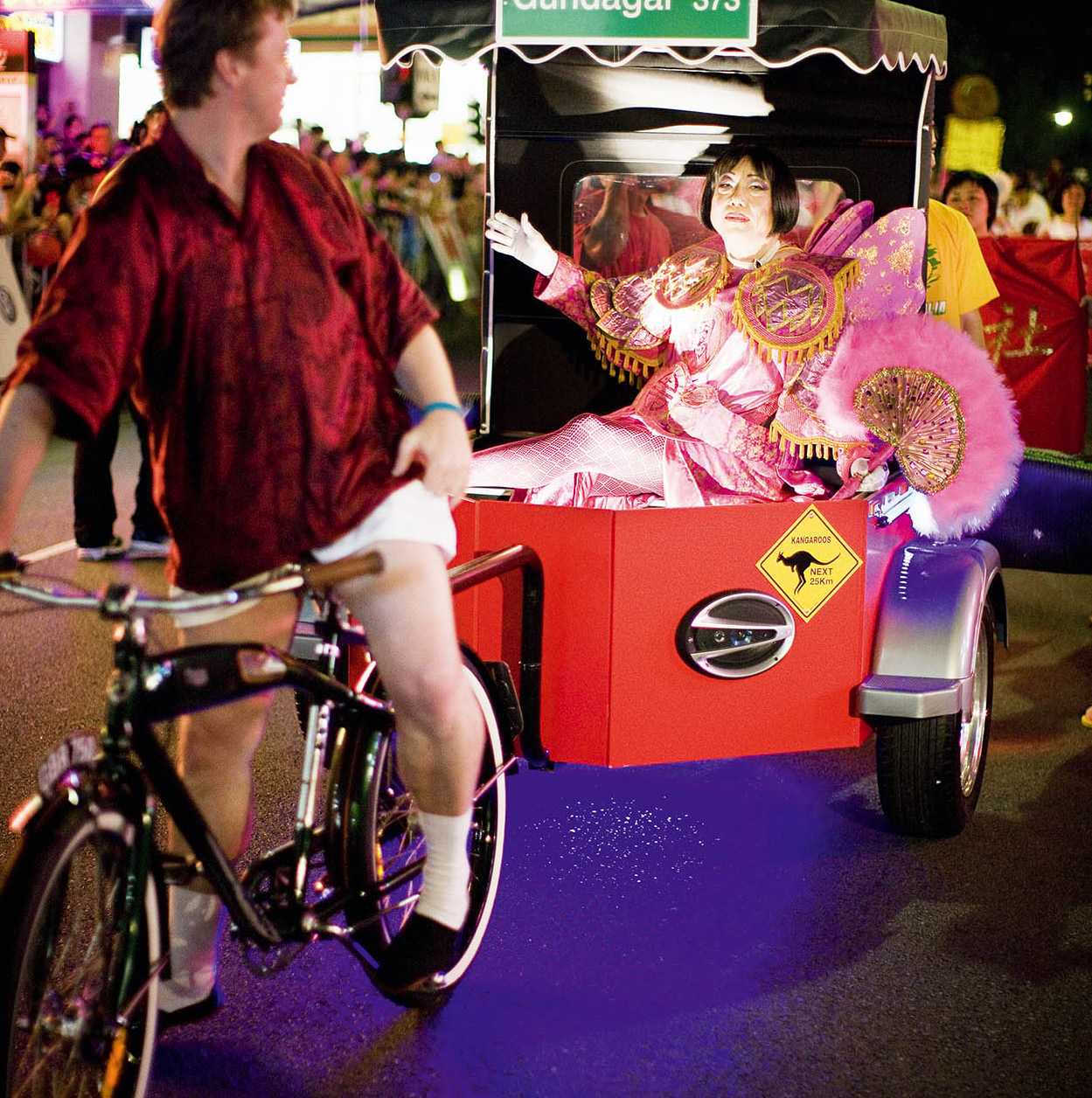

Sydney’s raucous Mardi Gras Parade

iStock

Paddington’s main thoroughfare, Oxford Street, which continues into the neighbouring suburb of Darlinghurst, is one of the hubs of Sydney’s large gay community (others include Surry Hills, Newtown and Erskineville). The Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade (www.mardigras.org.au), held here in late February/early March, has become a respected institution. The street is home to two good bookshops, Berkelouw and Ariel, and three of its more imaginative cinemas, the Chauvel, the Verona and the Palace Academy Twin. Victoria Barracks is Oxford Street’s renowned example of mid-19th-century military architecture, built by convicts to house a regiment of British soldiers and their families.

Take a harbour cruise to appreciate hidden beaches, islets, mansions old and new, and even a couple of unsung bridges. Various companies run half-day and full-day excursions, or you can hop aboard a commuter ferry and get off wherever you like. If you’re experienced, you could also rent a boat of your own and try weaving around the rest of the nautical traffic.

Fort Denison, situated on a small island, is graphically nicknamed ‘Pinchgut’. Before the construction of a proper prison, the colony’s more troublesome convicts were banished to the rock to subsist on a bread-and-water diet. In the middle of the 19th century the island was fortified to guard Sydney from the threat of a Russian military strike. Ironically, an attack finally came in World War II when an American warship, conducting target practice, hit old Pinchgut by mistake. You can visit Fort Denison, but only as part of a guided tour conducted by a national parks ranger (to book, tel: 02-9247 5033).

Taronga Zoo (www.taronga.org.au; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge), a 12-minute ferry ride from Circular Quay, has an excellent collection of native and exotic animals in a superb setting. Over the heads of the giraffes you can see across the harbour to the skyscrapers of Sydney. The zoo’s Nocturnal House features indigenous night-time creatures illuminated in artificial moonlight, unaware of onlookers. The Rainforest Aviary houses hundreds of tropical birds. If you arrange your visit around feeding times, you can watch the keepers distribute food while they give talks about their charges.

For excellent views of the city and harbour, catch a ferry to Cremorne Point. A paved path winds from here along the shore of Mosman Bay to the ferry wharf, a distance that can be covered easily in about 90 minutes, from where you can catch a ferry back to Circular Quay.

Sailing on Watsons Bay

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Another popular ferry destination is Watsons Bay in the Eastern Suburbs. This suburb began as a small fishing community and it still retains a village-like atmosphere. Doyle’s on the Beach seafood restaurant is located close to the ferry wharf, with wonderful harbour views. Nearby Camp Cove is a beach and picnic spot. A 30-minute walk from the beach along the foreshore leads to South Head, one of the headlands at the entrance to Sydney Harbour. The views are spectacular and the place gets packed each Boxing Day for the dramatic start of the Sydney to Hobart yacht race (www.rolexsydneyhobart.com).

Also accessible by ferry are Kirribilli – directly across the harbour from the city and also reached by foot over the Harbour Bridge – and Balmain, to the west of Circular Quay. Both places have lively café-and-restaurant strips and great harbour views from foreshore parks.

A quick trip from the city by bus or taxi is Vaucluse House (www.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au; Fri–Sun 10am–4.30pm, daily in Jan; charge). This splendid, 15-room mansion, begun in 1803, has its own beach, and comes complete with mock-Gothic turrets and battlements. A short walk away, down Coolong Road, is Nielsen Park, a bushland reserve that has a popular beach, as well as a café. There are good harbourside walks here too.

Surf Beaches

Further afield, both north and south of Sydney, are many kilometres of inviting beaches. Manly got its name when the first governor of the colony thought that the Aborigines sunning themselves on the beach looked manly. This pleasant resort, reached by ferry or Jetcat from Circular Quay, has back-to-back beaches – a sheltered harbour beach on one side, an ocean-facing surf beach on the other – which are linked by the Corso, a lively promenade full of restaurants and tables for picnickers.

Beyond Manly, beaches stretch all the way to Sydney’s northern limits. Among these are Curl Curl and Dee Why (which offer good surfing), Collaroy and Narrabeen (with sea pools ideal for families), and Newport, Avalon and Whale Beach (a good spot for surfing).

At the northern tip of the Sydney beach region is Palm Beach, which is in a class of its own. The beautifully manicured gardens and villas for millionaires occupy the hills of the peninsula behind the beach. You can get to Palm Beach by taking the 190 bus from outside Wynyard railway station in the city centre; the trip takes about an hour.

The golden sands of Bondi, Australia’s best-known beach

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Bondi is a favourite with surfers and an Australian icon. The varied characters on the sand range from ancient sun worshippers to topless bathing beauties, and include quite a few pink British backpackers. Families tend to congregate at the northern end, where there is a wading pool. The beach gets very crowded on summer weekends. Set back from the beach, Bondi Pavilion has a café and bar, and is a good place for people-watching. Behind it is Bondi’s main promenade and restaurant strip, Campbell Parade.

A string of lesser-known but lovely beaches stretch out to the south of Bondi, including Tamarama, Clovelly, Bronte and Coogee. These are best reached on foot by a scenic coastal walking track that starts at the southern end of Bondi beach. It takes about an hour to walk to Bronte; allow half an hour more for the Bronte to Coogee stretch. Buses run from Coogee to the city.

Olympic Sydney

Since the 2000 Games, Sydney’s magnificent, purpose-built Olympic Park (www.sydneyolympicpark.com.au) has been used for a range of activities and around 5,000 events are now staged there each year. The best way to get there is to catch a Parramatta Rivercat ferry from Circular Quay; these depart hourly and provide a 50-minute scenic river trip before you alight at Olympic Park wharf.

Sydney Olympic Park

iStock

The graceful, parabola-shaped centrepiece of Olympic Park, ANZ Stadium (www.anzstadium.com.au; guided tours from 11am), was Sydney’s premier Olympic venue; it now hosts football games of all codes, from rugby league to soccer and Aussie rules, as well as cricket games, and also stages the occasional concert.

Not far away is Sydney Olympic Park Aquatic Centre (www.aquaticcentre.com.au; Mon–Fri 5am–9pm, Sat–Sun 6am–8pm). Besides its pools, the centre has five spas, a river ride, spray jets, spurting ‘volcanoes’ and a water slide.

Surrounding these and other venues are extensive parklands, good for gentle walks and picnics. There is also a small number of cafés and restaurants.

Excursions from Sydney

Within striking distance of Sydney – by car, train, or sightseeing bus – a diverse choice of destinations shows the variety of attractions offered by New South Wales. Trips to any of these places will deepen your understanding of Australia and its culture.

Going West

A 90-minute trip west of Sydney by road brings you to the Blue Mountains 2 [map], a dramatic region of forested ravines and pristine bushland that is World Heritage listed. The Blue Mountains offer a wealth of adventure activities, art and craft galleries, and romantic escapes in grand country lodges or cosy bed and breakfasts.

The name derives from the mountains’ distinctive blue haze, produced by eucalyptus oil evaporating from millions of gum trees. Well-marked walking trails criss-cross Blue Mountains National Park, passing streams and waterfalls, descending into cool, impressive gorges, and snaking around sheer cliffs. This breath-taking environment is easily reached from Sydney, either by road or on a two-hour rail journey. Trains run there several times daily from Central Station.

The vast Jamison Valley lies below the Three Sisters

Dreamstime

Scenic Cableway

iStock

The region’s best-known rock formation is the Three Sisters, a trio of pinnacles best viewed from Katoomba, the largest of 26 mountain towns. The Scenic Railway, the world’s steepest passenger-carrying railway, descends from the cliff-top at Katoomba into the Jamison Valley. You can walk down a series of steps by the Three Sisters, stroll along a cool and refreshing trail and catch the Katoomba Scenic Rail to the top. Above, the Scenic Skyway carries passengers along a cableway 206 metres (675ft) above the valley floor. The Scenic Cableway descends over 500 metres (1,600ft) into the Jamison Valley.

For a less touristy view of the Blue Mountains, drive to the lookout at Govetts Leap, near Blackheath, 12km (7.5 miles) west of Katoomba. The panorama is magnificent.

Of the numerous walking trails in the Blue Mountains, many involve a steep descent into a valley and a steep climb back to the top. For information about walks in the area, see www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au.

For more than a century, spelunkers, hikers and ordinary tourists have admired the Jenolan Caves, at the end of a long, steep drive down the mountains west of Katoomba. Guided tours (tel: 1300 763 311; www.jenolancaves.org.au; daily 9am–4.45pm; charge) through the spooky but awesome limestone caverns last about an hour and a half. The atmosphere inside the caves is cool in summer, warm in winter, and always damp.

Heading North

Just north of Sydney is Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. This area of unspoiled forests, cliffs and heathland fringing the Hawkesbury River, is home to numerous species of animals and birds. There are also many good walking trails through untouched bushland. West Head Lookout, on top of a headland, gives outstanding views of the river and ocean. The Aborigines who lived in this area long before the foundation of New South Wales left hundreds of rock carvings – mostly pictures of animals and supernatural beings. The information centre at Bobbin Head Road, Mount Colah (tel: 02-9472 8949) has maps pinpointing the locations of the most interesting carvings, as well as showing the park’s network of trails.

Close to Sydney, the Hunter Valley is a lush, wine-growing region in New South Wales

Tourism NSW

The Hunter

Australia is one of the world’s major wine-producing countries. The Hunter Valley, a two-hour drive north from Sydney, is the premier wine-growing area of New South Wales. The Hunter’s 120 or so wineries harvest grapes in February and March, and welcome visitors throughout the year. The gateway to the Pokolbin region, where the majority of the Lower Hunter Valley wineries are located, is Cessnock, 195km (121 miles) north of Sydney. The tourist information centre, in the nearby town of Pokolbin, supplies touring maps and brochures, or you can join a day tour from Sydney.

Most of the Hunter wineries are open for cellar-door tastings. Some of the major establishments include Tyrell’s, Lindemans, Wyndham Estate, Rosemount Estate, the Rothbury Estate and the McWilliams Estate.

Newcastle, the commercial centre of The Hunter, is located approximately 170km (106 miles) to the north of Sydney. It’s a coalmining and shipbuilding centre, and also offers well-developed recreational activities on the Pacific, the Hunter River and Lake Macquarie, the largest saltwater lake in Australia, very popular with weekend sailors and fishermen from near and far.

Further north, Port Stephens offers safe swimming beaches, a range of water activities and good fishing. Its bay is home to dozens of bottlenose dolphins, which can be viewed up close on a cruise.

In the far north of New South Wales, 790km (490 miles) from Sydney, Byron Bay provides wonderful beaches and great surf. Whale-watching boat trips offer an opportunity to see humpback whales when they migrate along the coast here in June–July and September–October. The town is a haven for alternative lifestylers and millionaires.

Remote Lord Howe Island, home to some fabulous scenery

iStock

Lord Howe Island

In the South Pacific, 600km (360 miles) east of Port Macquarie, Lord Howe Island is the world’s most southerly coral isle. The snorkelling and scuba diving is splendid here, but non-swimmers can go out in a glass-bottom boat. There are also numerous walking trails, many birds and some unique vegetation.

Forests, beaches, mountains and all, Lord Howe Island only amounts to a speck in the ocean – around 1,300 hectares (3,220 acres) – with a population of about 300 and a couple of cars. Bicycles and motorbikes are ideal for getting around as the roads are very quiet. You can fly out from Sydney or Brisbane in a couple of hours.

Winter sports in the Snowies

Tourism NSW

Heading South

Thanks to a bit of historical gerrymandering, Jervis Bay, 200km (124 miles) south of Sydney, and 260km (161 miles) northeast of Canberra, is not actually part of New South Wales, but a separate Commonwealth territory, like the Australian Capital Territory. New South Wales surrendered the area to Canberra in the early 20th century, in case the future capital ever needed a seaport. The coastal enclave today includes an uncommon combination of facilities: inviting dunes and beaches rub shoulders with the Royal Australian Naval College, a missile range and Booderee National Park. Jervis, named after an English admiral, is correctly pronounced ‘Jarvis’, although locals are starting to rhyme it with nervous. The sand on Jervis Bay beaches is dazzling white and the sea is crystal clear. Dolphin Watch Cruises (tel: 02-4441 6311; www.dolphinwatch.com.au) operate from the town of Huskisson – sometimes you get to see migratory whales as well as dolphins. Not far away, a delightful glade called Greenpatch, in Booderee National Park, offers some remarkably tame wildlife, including kangaroos, wallabies and multicoloured birds.

For more beautiful beaches and tame wildlife, head 95km (60 miles) south from Huskisson to idyllic Murramarang National Park, just before the town of Batemans Bay. There are cabins and camping grounds here, as well as walking trails.

The Snowy Mountains

If you’ve come to Australia in search of snow, you need go no further than the southeastern corner of New South Wales. Skiing in the Snowy Mountains 3 [map] (known as the ‘Snowies’) is usually restricted to July, August and September. But even in the antipodean spring a few drifts of snow remain to frame the wild flowers of the Australian Alps. At the top of this world is Mt Kosciuszko, at 2,230 metres (7,308ft), named after an 18th-century Polish patriot by a 19th-century Polish explorer. This is the birthplace of three important rivers, the Murray, the Murrumbidgee and the Snowy.

Kosciuszko National Park is made up of approximately 6,700 sq km (2,600 sq miles) of the kind of alpine wilderness you won’t see anywhere else: buttercups and eucalyptus and snow, all together in the same breath-taking panorama. Numerous hiking trails make for beautiful summer walks, and outside of the white season you’ll barely see anyone. Cars must be equipped with snow chains from 1 June to 10 October. However, even during the summer months the weather can change for the worse at very short notice, so be sure always to carry a warm, waterproof jacket. The best-known ski resorts in this area are Thredbo and Perisher Valley.

New South Wales Outback

Although New South Wales is the most populous and productive state (in both manufacturing and farming), as it extends into the seemingly infinite expanse of the Australian Outback, the population becomes much more thinly spread across the hard brown earth.

Dubbo, a five-hour drive from Sydney, is the sort of place where the Old Gaol, meticulously restored, is a prime attraction, gallows and all. Just out of town, the Taronga Western Plains Zoo (www.taronga.org.au/taronga-western-plains-zoo; daily 9am–5pm; charge) is Australia’s premier open-range zoo – a cageless convention of koalas, dingoes and emus, plus giraffes, zebras and monkeys.

Lightning Ridge, in the back of beyond near the Queensland border, enjoys one of the most evocative of Outback names. Fortune hunters know it well as the home of the precious black opal. Tourists are treated to demonstrations of fossicking (recreational prospecting), and there are opportunities to shop for opals.

Bourke is a small town on the Darling River whose name has come to signify the loneliness of the Outback, where dusty tracks are the only link between distant hamlets. ‘Back of Bourke’ is an Australian expression for a place that is extremely remote. Bourke looks a lot bigger on the map than on the ground.

Broken Hill (population around 20,000) is about as far west as you can go in New South Wales, almost on the border with South Australia. It’s so far west of Sydney, there’s a half-hour time difference. The town is legendary for its mineral wealth – it has produced millions of tons of silver, lead and zinc. Tourists can visit the mines, either underground or on the top. The neatly laid-out town, with streets named after various minerals – Iodide, Kaolin, Talc – has become an artistic centre, with works by Outback painters on show in numerous galleries. Pro Hart, one of Australia’s best-known and most prolific painters, was a long-time Broken Hill resident. The School of the Air and the Royal Flying Doctor Service – both Outback institutions – give a further taste of life in the back of beyond.

When the new nation was proclaimed at the turn of the 20th century, the perennial power struggle between Sydney and Melbourne reached an awkward deadlock. Each of the cities offset its rival’s claim to be the national capital. So they carved out a site in the rolling bush 300km (185 miles) southwest of Sydney, and it soon began to sprout clean, white, official buildings, followed by millions of trees and shrubs. Out of conflict emerged a green and pleasant compromise, far from the pressures of the big cities. Where sheep had grazed, the young Commonwealth raised its flag. As compromises go, it was a winner.

The Australian Parliament House

iStock

Designing the Capital

To design a model capital from scratch, Australia held an international competition. The prize was awarded in 1912 to the American architect Walter Burley Griffin. He had grand designs, but it took longer than anyone imagined to transfer his plan from the drawing board to reality, owing not only to the distractions of two world wars and the Depression, but also to a great deal of wrangling. Burley Griffin, a Chicagoan of the Frank Lloyd Wright school, put great emphasis on coherent connections between the settings and the buildings, and between the landscape and the cityscape. Canberra’s complete creation story is told in the National Capital Exhibition (Commonwealth Park, Regatta Place; tel: 02-6257 1068; www.nationalcapital.gov.au).

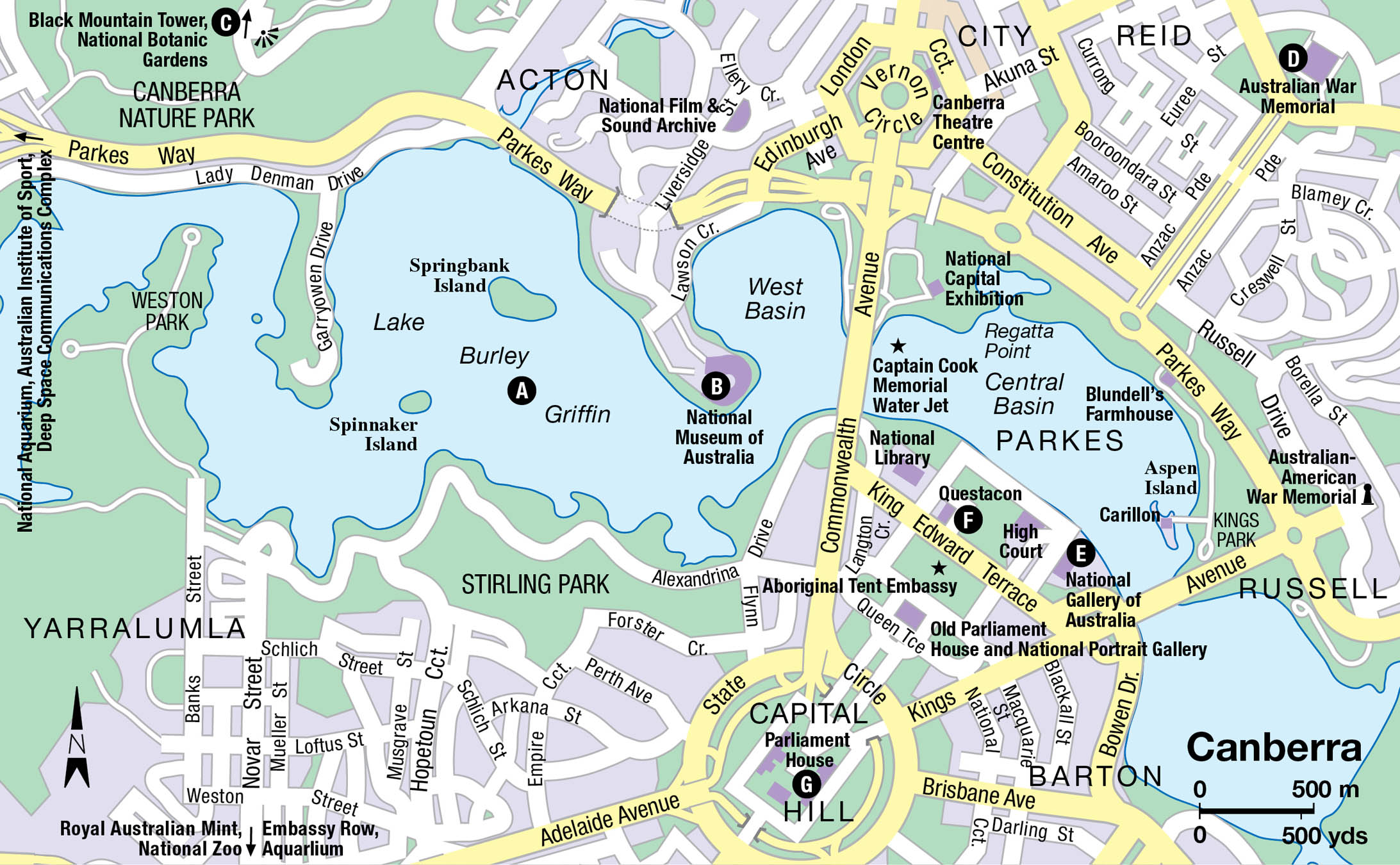

Canberra 4 [map], at the heart of the Australian Capital Territory, has a population of about 370,000. Although the city is an educational and research centre, it is essentially a company town – and the local industry is government. The ministries are here, and the parliament with its politicians, lobbyists and hangers-on, and so are the foreign embassies. The Royal Military College Duntroon, Australia’s first military college, founded in 1911, is based in Canberra, as is the Australian National University and the Australian Institute of Sport. In spite of this considerable enterprise, Australia’s only sizeable inland city is both uncrowded and relaxed.

City Sights

There are several good ways to see Canberra, but on foot isn’t one of them; the distances are greater than you think. If you do want to walk, many of the main attractions are found near Lake Burley Griffin – but you’ll still need three or four hours. It’s a good idea to sign up for a bus tour; they come in half-day and all-day versions. Or take a City Sightseeing bus, which runs a 25km (15-mile) route stopping at all the main sights. You buy a 24-hour ticket, then hop on and off at will. Alternatively, you can drive yourself around the city or hire a bike, following itineraries that are mapped out in a free sightseeing pamphlet available from the Canberra Visitor Information Centre (Northbourne Avenue, Dickson; tel: 1300 554114; www.visitcanberra.com.au; 9am–5pm weekdays, till 4pm at weekends).

An effective starting place for a do-it-yourself tour is Regatta Point, which overlooks the man-made Lake Burley Griffin A [map]. Cleverly created in the middle of town, the lake – 35km (22 miles) around – is generously named after the town planner who realised the value of water for recreation as well as scenic beauty. You can enjoy fishing, sailing and windsurfing here, or hop on a sightseeing boat with Southern Cross Cruises (tel: 02-6273 1784; www.cscc.com.au; charge). Whooshing 147 metres (482ft) into the sky from the lake everyday, between 2pm and 4pm, the Captain James Cook Memorial is a giant water jet that honours the Yorkshireman’s landing on Australia’s East Coast in 1770. The National Carillon, another monument rising from Lake Burley Griffin (actually from a small island), was a gift from the British government. Apart from concert recitals, it tells the time every 15 minutes, taking its tune from London’s Big Ben.

In a prime position at the tip of the Acton Peninsula is the excellent National Museum of Australia B [map] (www.nma.gov.au; daily 9am–5pm; free), a social history museum with themed galleries relating to the land, the people and the nation. The First Australians Gallery looks unflinchingly at the plight of the Aboriginal people after Europeans arrived, from the early massacres to the 20th-century government policy of taking Aboriginal children from their parents (the ‘Stolen Generations’).

North of the Lake

To get the best view of Canberra and surrounds, drive to Black Mountain. There are free lookouts here, or you can pay for a 360-degree perspective by going up the Black Mountain Tower C [map] (tel: 02-6219 6120; www.telstratower.com.au; daily 9am–10pm; charge), which stands 195 metres (640ft) high. A viewing platform circles the structure towards the top, and the designers couldn’t resist adding a café and a revolving (and expensive) restaurant.

On the eastern slopes of Black Mountain, the National Botanic Gardens (www.anbg.gov.au; daily 8.30am–5pm; free) are entirely devoted to Australian flora – the most comprehensive collection in the world. In spite of Canberra’s mostly mild, dry climate, numerous rainforest specimens flourish under intensive care. Walter Burley Griffin was so fascinated by the native trees and plants of Australia that he included this place in his original plan.

The only part of the capital designed with pedestrians in mind is the area around the Civic Centre. The original business and shopping district opened in 1927 – by Canberra standards that’s ancient history – and comes complete with symmetrical white colonnaded buildings in a mock-Spanish style. Nearby are modern shopping malls, the Canberra Theatre Centre on London Circuit, and a historic merry-go-round in Petrie Plaza.

Australian War Memorial

Australian Capital Tourism

A more conventionally styled dome covers the vast Australian War Memorial D [map] (www.awm.gov.au; daily 10am–5pm; free), which is a sandstone shrine climaxing a ceremonial avenue called Anzac Parade. There are war memorials all over Australia, but this is the definitive one, with walls poignantly inscribed with the names of more than 100,000 Australian war dead. Beyond the statues and murals, the memorial is the most-visited museum in Australia. Items displayed in its 20 galleries include uniforms, battle maps, and plenty of hardware, from rifles to a World War II Lancaster bomber.

Closer to the lake is one final military monument: the 11-metre (36ft) tall Australian-American War Memorial, a slim aluminium shaft supporting a stylised eagle. It was paid for by public contributions to acknowledge US participation in the defence of Australia during World War II.

Australia’s National Gallery

iStock

South of the Lake

The mostly windowless walls of the National Gallery of Australia E [map] (Parkes Place; tel: 02 6240 6411; www.nga.gov.au; daily 10am–5pm; free) were designed to enclose ‘a museum of international significance,’ as official policy decreed. The enterprise has succeeded on several levels, showing off artists as varied as Monet and Matisse, Pollock and de Kooning, along with an honour roll of Australian masters, including Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker. Further indications of the range of interests represented here are the displays of art from Pacific island peoples, Africa, Asia and pre-Columbian America. The gallery also plays host to touring international exhibitions.

A high point of the National Gallery is the collection of Australian Aboriginal art: intricate human and animal forms on bark from northern Australia, and deeply spiritual compositions of dots and whorls from the central deserts, which have evolved from ephemeral sand art to vivid polymer paint on board. The gallery also has a sculpture garden overlooking Lake Burley Griffin.

What’s in a Name?

The name of Australia’s new capital city, derived from an Aboriginal word for ‘meeting place’, was officially chosen in 1913 from a huge outpouring of suggestions. Some of the more serious citizens wanted it to have a name as uplifting as Utopia or Shakespeare. Others devised classical constructions, for example Auralia and Austropolis. The most unusual proposal was a coinage designed to soothe every state capital: Sydmeladperbrisho. After that mouthful, the name Canberra came as a relief.

One of Canberra’s best kid-friendly attractions is Questacon, the National Science and Technology Centre F [map] (King Edward Terrace; tel: 02-6270 2800; www.questacon.edu.au; daily 9am–5pm; charge), a hands-on science museum that is very much geared towards children and teenagers. There are more than 200 exhibits in seven galleries that explore the science behind sports and athletics, everyday technology and natural phenomena.

Also on the lakefront, the National Library (Parkes Place; tel: 02-6262 1111; www.nla.gov.au; Mon–Thur 9am–9pm, Fri–Sat 9am–5pm, Sun 1.30–5pm; free) houses more than 2 million books. This institution serves scholars and other libraries, and mounts exhibitions of rare books and maps. Its reading room houses an extensive selection of overseas newspapers and magazine publications. There are guided tours (free), a bookshop, and a café.

Canberra’s Old Parliament House became the seat of government in 1927 and fulfilled that role until it was replaced in 1988. It is now the home of the National Portrait Gallery (King Edward Terrace; tel: 02-6102 7000; www.portrait.gov.au; daily 10am–5pm; charge). Outside it is the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, a semi-permanent structure claiming to represent the rights of Australian Aborigines that has been around in one incarnation or another since 1972 (despite coming under attack several times).

A new parliament building to replace the old one was dedicated by Queen Elizabeth II in the bicentennial year, 1988. Parliament House G [map] (tel: 02-6277 5399; www.aph.gov.au; Mon–Fri 9am–5pm; free guided tours) is worth a visit,its interior representing the best in Australian art and design. The Great Hall is dominated by a tapestry 20 metres (66ft) wide. The combination of an unusual design (partially underground), as well as exploding building costs, made the new complex a cause célèbre during its construction, especially when taxpayers noted the lavish offices, bars, swimming pool and a sauna.

Meanwhile, they’re minting it in the southwestern district of Deakin, and you can take a look for yourself. The Royal Australian Mint (www.ramint.gov.au; Mon–Fri 8.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–4pm; free) has a visitors’ gallery overlooking the production line where the country’s coins are punched out. The factory also moonlights to produce the coinage of several other countries. The Mint’s own museum contains coins and medals of special value.

Other Canberra attractions include the National Film and Sound Archive (www.nfsa.gov.au) and the Australian Institute of Sport (Leverrier Street, Bruce; tel: 02 6214 1111; www.auspot.gov.au/ais), where there are athlete-led guided tours of the Institute (daily at 10am, 11.30am, 1pm, 2.30pm).

Out of Town

Animal lovers don’t have far to go for a close encounter with kangaroos, echidnas, wombats and koalas. The National Zoo and Aquarium (02-6287 8400; www.nationalzoo.com.au; daily 9am–5pm; charge) is only a few kilometres southeast of the city centre, in Yarralumla. You can walk through acrylic tunnels while sharks cruise past. The bird population includes parrots, kookaburras, cockatoos and emus.

The Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve (tel: 13 22 81; www.tidbinbilla.com.au; daily 9am–6pm, 9am–8pm in summer), 40km (25 miles) southwest of Canberra, is a much bigger affair – thousands of hectares of bushland where kangaroos, wallabies and koalas flourish. Next to this unspoilt wilderness, the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (tel: 02-6201 7880; www.cdscc.nasa.gov; daily 9am–5pm), one of only three deep-space tracking stations in the world, operates in conjunction with NASA, the US space agency. The Complex has several exhibitions on space exploration.

Another day in Surfers Paradise

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

QUEENSLAND

Queensland provides just about everything that makes Australia so desirable, and then adds some spectacular exclusives. The sun-soaked state gives you the choice of flashy tourist resorts, remote Outback towns, a modern metropolis, rainforest, desert or apple orchard. But the most amazing attraction of all is Queensland’s offshore wonderland – the longest coral reef in the world, the Great Barrier Reef.

Queensland was founded in 1824 as a colony for incorrigible convicts, the ‘worst kind of felons’, for whom not even the rigours of New South Wales were a sufficient deterrent. In an effort to quarantine criminality, free settlers were banned from an 80km (50-mile) radius of the penal settlement in what is now Brisbane. But adventurers, missionaries and hopeful immigrants couldn’t be held back for long. Queensland’s pastureland attracted many eager squatters, and in 1867 the state joined the great Australian gold rush with a find of its own. Prosperity for all seemed to be just around the corner.

Mining still contributes generously to Queensland’s economy. Above ground, the land is kind to cattle and sheep, and produces warm-hearted crops like sugar, cotton, pineapples and bananas. But tourism is poised to become the biggest money-spinner, for Queensland is Australia’s vacation state, welcoming tourists (domestic and international) to wild tropical adventurelands in the far north, and the glitter of the Gold Coast in the south. The busiest gateways to all of this are the state capital, Brisbane, and the port of Cairns, which has become one of Australia’s most popular tourist destinations.

As befits a subtropical city with palm trees and back-garden swimming pools, Brisbane 5 [map] has a pace so relaxed you’d hardly imagine its population is over 2 million. The skyscrapers, some quite audacious, have gone a long way towards overcoming the ‘country-town’ image, but enough of the old, elegant, low-slung buildings remain as a reminder of former days; some are wonderful filigreed Victorian monuments, some are done up in bright, defiant colours. As well as having its own attractions, the city is also a handy gateway to nearby tourist sites such as the Gold Coast and Fraser Island.

The towers of Brisbane line the river

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

In 1859, when Brisbane’s population was all of 7,000, it became the capital of the newly proclaimed colony of Queensland. The colonial treasury contained only 7.5 pence, and within a couple of days even that was stolen. Old habits of the former penal colony seemed to die hard.

The capital’s location, on a bend in the Brisbane River, has made some memorable floods possible over the years – such as in 2010–11, when 38 people were killed and parts of the city were declared a disaster zone – but it sets an attractive stage for Australia’s third-largest city. Spanned by a network of bridges (the first dated 1930), the river continues through the suburbs to the beaches and islands of Moreton Bay, 29km (18 miles) from central Brisbane. Some of Australia’s most celebrated types of seafood come from here, notably the gargantuan local mud crabs and the Moreton Bay bug. Despite its unappealing name, this creature, related to the lobster, is a gourmet’s joy.

Up the hill, on Wickham Terrace, stands an unusual historic building, the Old Windmill – also known as the Old Observatory – built by convicts in 1829. Design problems foiled the idea behind the windmill, which was to grind the colony’s grain, and the energy of the wind had to be replaced by a convict-powered treadmill.

The nearby Roma Street Parkland is a diverse area of waterfalls, lakes, misty crannies of tropical vegetation, and floral displays with their own ecosystem of insects and birds. It is said to be the world’s largest urban subtropical garden.

Queen Street shopping

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

King George Square, next to City Hall, and the nearby Anzac Square, are typical of the open spaces that make the Central Business District (CBD) welcoming and pedestrian-friendly. Queen Street Mall is flanked by bustling stores and interspersed with shady retreats and cafés. Here, on a fine day, visitors from cooler climes should take a seat to enjoy the warm sun and watch the passers-by. Or you can stroll along Albert Street, from King George Square to the City Botanic Gardens.

Where central Brisbane fits into the bend in the river, the City Botanic Gardens (open 24 hours) turn the peninsula green with countless species of Australian and exotic trees, plants and flowers. Parliament House (tours Mon–Fri 9am–4.15pm), built in the 19th century in Renaissance style, overlooks the gardens and is the headquarters of the state’s legislative assembly.

Across the Goodwill footbridge from the Botanic Gardens, or Victoria Bridge from the centre of town (and also accessible by ferry), is one of the city’s main focal points, South Bank, a precinct of parks, gardens, restaurants, cafés and many other attractions stretching along the southern bank of the river.

Gallery of Modern Art

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

At its northern end is the Queensland Cultural Centre, which puts most of Brisbane’s cultural eggs in one lavish, modern basket. The Centre includes the Queensland Art Gallery (www.qag.qld.gov.au; Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat–Sun 9am–5pm; free), the Gallery of Modern Art (same hours and website as gallery; free), the Queensland Museum (www.southbank.qm.qld.gov.au; daily 9.30am–5pm; free) and its offshoot Sciencentre (same hours as museum; charge), an interactive science museum aimed at kids and teens. Here too is the Queensland Performing Arts Centre (www.qpac.com.au), with several performance spaces.

To the south of the Cultural Centre, and linked to it by a beautiful bougainvillea-clad arbour, are the South Bank Parklands. The attractions here include a market (Fri 5–10pm, Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 9am–5pm) and an artificial beach (Streets Beach). There is also a diverse array of restaurants, making this the place to head for on a sunny day, for an outdoor meal. Brisbane enjoys a reputation for chefs who make good use of their state’s natural resources: mud crabs, avocados, macadamia nuts, mangoes, barramundi, coral trout and oysters, to name a few.

For a classic Brisbane pub, check out the Breakfast Creek Hotel (2 Kingsford Smith Drive; tel: 07-3262 5988; www.breakfastcreekhotel.com; daily 10am–2am), built in 1889, on the north side of a bend in the Brisbane River, about 5km (3 miles) east of the CBD. If you seek bars and restaurants, Fortitude Valley, just outside the CBD, is a lively precinct. Brunswick Street, the valley’s main thoroughfare, is lined with nightclubs, street cafés, ethnic restaurants and arty little shops. This suburb is also the location of Brisbane’s Chinatown. At weekends a market operates. Nightlife there can be fun, but it’s wise to take a taxi when heading home after dark. Linking Fortitude Valley to Kangaroo Point is Story Bridge, a city landmark that you can climb with Story Bridge Adventure Climb (170 Main Street; tel: 1300 254 627; www.sbac.net.au; charge).

Botanic Gardens Mt Coot-tha

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

To escape the heat and rush of the city, try Brisbane Botanic Gardens Mt Coot-tha (daily 8am–5.30pm; free), in Toowong, 7km (4 miles) west of the city centre. Covering 52 hectares (128 acres), these are the largest tropical and subtropical gardens in Australia and feature a giant dome enclosing 200 species of tropical plants.

From here it’s about 11km (7 miles) to Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary (www.koala.net; daily 9am–5pm; charge), one of the country’s best-known collections of native animals. By boat from North Quay in the city centre, the trip is several kilometres longer, taking one and a half hours. The stars of the show, of course, are the koalas, mostly sleeping like babies, clinging to their eucalyptus branches.

Koala mascot

The koala is Queensland’s official emblem. Its only occupation is eating eucalyptus leaves, the odour of which impregnates its whole body, providing both antiseptic protection and a deterrent to predators.

The islands of Moreton Bay, some of which are unpopulated, make this a vast fishing and sailing paradise. St Helena Island (tel: 1300 438 787; www.sthelenaisland.com.au; charge), now a national park, became a penal settlement in the 1860s and remained a high-security prison until the 1930s; the excellent tours, which set out across the bay from Manly on the Cat-O’-Nine Tails, include a night-time ghost tour where actors re-enact scenes from the convict era. Moreton Island features Mt Tempest, at 285 metres (935ft) the world’s highest stabilised coastal sand dune. On North Stradbroke Island, the Aboriginal community has developed a 90-minute tour called the Goompi Trail (tel: 07-3821 0266; charge) where an Aboriginal guide explains the flora and fauna, with Dreamtime stories, bush tucker (food) and traditional medicine.

The Gold Coast

South of Brisbane, within day-trip distance if you’re rushed, the Gold Coast 6 [map] is a Down-Under version of Miami Beach. Although it may be overexploited (and best avoided during ‘Schoolies’ week in late November/early December, when Australia’s high-school leavers celebrate their graduation with raucous partying) it’s certainly dynamic, with lots of opportunities for recreation. And the beach – anything from 30–50km (19–30 miles) of it, depending on who’s doing the measuring – is a winner. More than 20 Gold Coast surfing beaches, all patrolled by lifesavers, form the backdrop for activities such as swimming, sailing, boating, surfboarding and windsurfing.

The trip down the Pacific Highway south from Brisbane (78km/49 miles, roughly an hour’s drive) is a study in Australian escapism. In the midst of forest and brushland grows a seemingly unending supply of amusement parks, luring fun-seekers with attractions for all the family; these diverting parks include Dreamworld (tel: 07-5588 1111; www.dreamworld.com.au; daily 10am–5pm; charge), Sea World (tel: 07-5591 0000; seaworld.com.au; daily 9.30am-5pm; charge) and Wet ’n’ Wild (tel: 13 33 86; wetnwild.com.au; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge). Warner Bros Movie World (tel: 07 5573 3999; www.movieworld.com.au; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge), one of the biggest, offers a Hollywood-style experience, including stunt shows, special effects and amusement rides.

Enjoying the surf on the Gold Coast

Tourism Australia

The Gold Coast’s Dreamworld operates an attraction claimed to be ‘one of the fastest rides in the world’, the Tower of Terror II (based on the original, but relaunched in 2010 – faster than ever). Visitors also flock to action-packed rides with names like Wipeout and Cyclone, watch adventure films on a huge screen or (if they want something quieter) cuddle a koala. Other Gold Coast theme-park attractions include Wet ’n’ Wild, which contains a giant wave pool, a white-water ride and a seven-storey speed slide.

Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

Nature-lovers can also enjoy Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary (tel: 07-5534 1266; www.currumbin-sanctuary.org.au; daily 8am–5pm; charge), where masses of squawking rainbow lorikeets are fed each morning and evening. Other animals featured include koalas, kangaroos, Tasmanian devils, snakes and crocodiles. Currumbin is down towards the southern extremity of the Gold Coast, which ends at Point Danger. Beyond here lies New South Wales.

Surfers Paradise

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

The essence of the Gold Coast is Surfers Paradise, as lively as any seaside resort in the world and much addicted to high-rise living. Here, when you’re not sunbathing, swimming or surfing, you can go bungee jumping or just window-shop, eat out, socialise or wander through the malls, one of which, Raptis Plaza, is adorned by a full-scale replica of Michelangelo’s David. The pace is hectic, and the revelry never stops. To unwind, take a leisurely boat cruise along the Southport Broadwater or the canals. Another Surfers Paradise landmark, not far from Sea World, is Palazzo Versace, the world’s first Versace Hotel, billed as ‘six star’ and filled with all kinds of designer trappings.

Surfers Paradise is approached through a thicket of petrol stations, fast-food outlets and motels. Ahead you’ll see a skyscrapered horizon of tall, slim apartment blocks interspersed with bungalows. The high-rise skyline of Surfers Paradise must now rank with Ipanema, Miami and Cannes for architectural overkill.

The lush green backdrop to the Gold Coast is known as the Hinterland. The area encompasses luxuriant subtropical rainforests, waterfalls and bushwalking tracks, mountain villages and guest houses, craft galleries and cosy farm-stay accommodation. Lamington National Park, a World Heritage area, is well worth visiting and is an easy day-trip from Surfers Paradise.

The Sunshine Coast

For the sandy perfection of the Gold Coast with less commercialism (although they’re working on it), try the resorts of the Sunshine Coast 7 [map], north of Brisbane. Some of Australia’s best surfing is found here.

Noosa

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications

The resort closest to Brisbane, Caloundra, has a beach for every tide. The northernmost town on the Sunshine Coast, Noosa, used to be a sleepy little settlement, and the weekend haunt of local farmers and fishermen. That was in the 1960s, before the surfers, and the trendsetters from Sydney and Melbourne arrived, but it’s still very laid back. Noosa National Park, a sanctuary of rainforest and under-populated beaches, occupies the dramatic headland that protects Laguna Bay from the sometimes squally South Pacific breezes. Fraser Island (for more information, click here) is easily reached from here.

This whole stretch is home to some of Queensland’s most gorgeous coastline. Beaches such as those fronting the towns of Maroochydore and Coolum are gems.

The Sunshine Coast Hinterland is laden with plantations of sugar cane, bananas, pineapples and passion fruit. The area is also a centre of production of the prized macadamia nut. Above Nambour, the principal town of the Hinterland, is the Blackall Range, a remnant of ancient volcanic activity. Attractive Blackall towns such as Montville and Maleny offer crafts shops, cafés and tearooms.

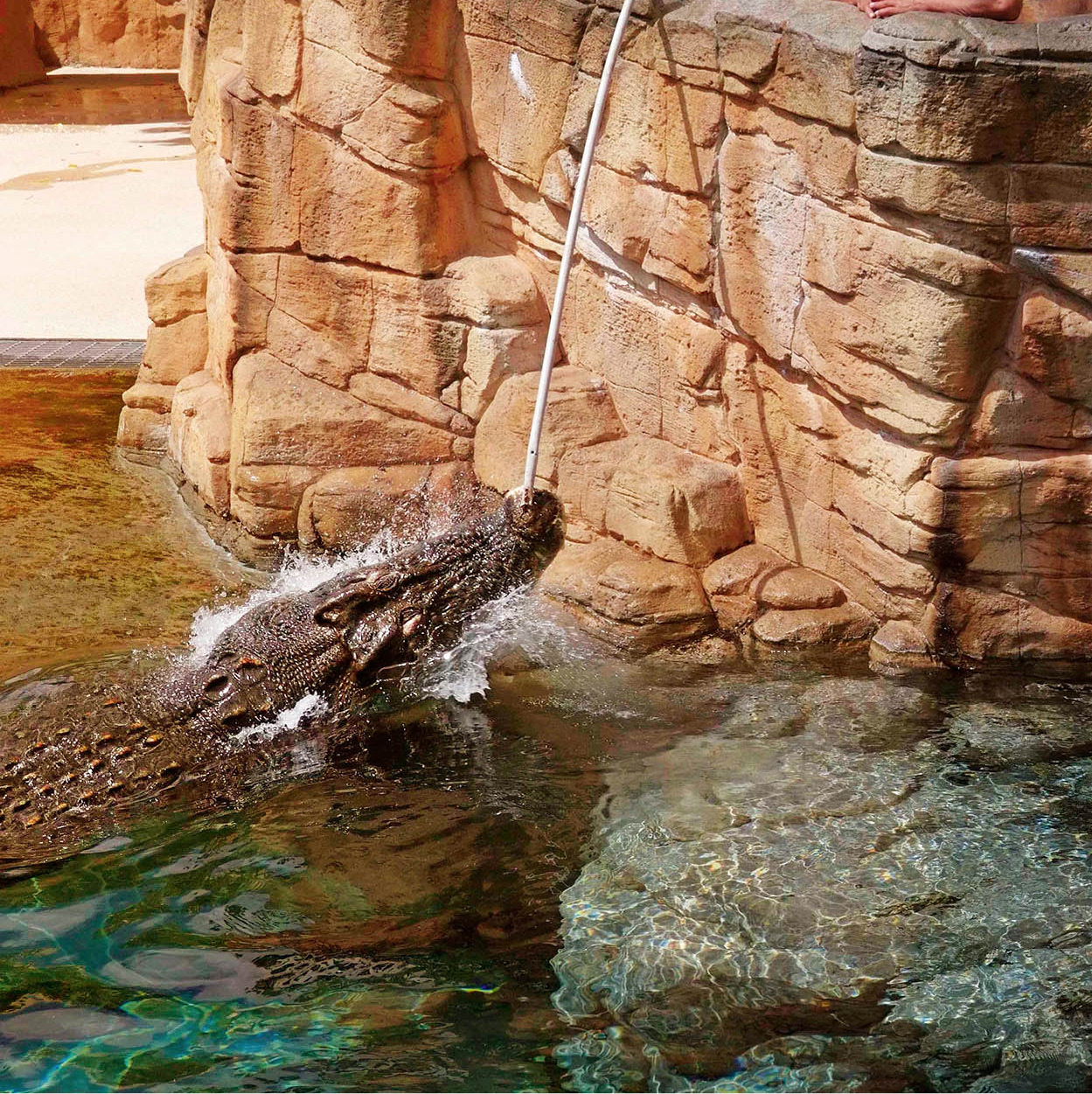

To the south, just off the Bruce Highway near Beerwah, is Australia Zoo (tel: 07-5436 2000; www.australiazoo.com.au; daily 9am–5pm; charge). Made famous by the late Steve Irwin, the zoo has a wide variety of Australian wildlife, as well as many exotic species.

Heading off to explore the reef

Pro Dive Cairns

Australia’s biggest and most wonderful sight, the Great Barrier Reef 8 [map], lies just below the ocean waves. Millions of minuscule coral polyps multiply and grow into an infinite variety of forms and colours here, to create the world’s largest living phenomenon. The reef is home to at least 350 different types of coral. It stretches as far as you can see and beyond: more than 2,900km (1,430 miles) of submerged tropical gardens, sprinkled with hundreds of picture-perfect islands.

Observed more intimately through a diver’s mask, the reef is the spectacle of a lifetime, like being inside a boundless tropical fishbowl among the most lurid specimens ever conceived. Watch as a blazing blue-and-red fish darts into sight, pursuing a silver cloud of a thousand minnows; a sea urchin stalks past on its needles; a giant clam opens its convoluted, fleshy mouth as if sighing with nostalgia for its youth, a century ago.

In 1770, James Cook was exploring Australia’s east coast and literally stumbled upon the Great Barrier Reef when the Endeavour was gored by a lurking outcrop of coral. Patching the holes as best they could, the crew managed to sail across the barrier, and the vessel limped onto the beach at what is now Cooktown, where some major repairs had to be improvised.

The giant reef was proclaimed a marine park by the Australian Government in 1975, and placed on the World Heritage list in 1981, becoming the biggest World Heritage area in existence. It’s now managed by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (www.gbrmpa.gov.au), but is under threat from government-approved industrial activity within its boundaries, including dredging, ocean floor dumping and an increase in large tanker-ship traffic.

Hamilton Island chapel

iStock

There are many ways of appreciating the reef, from glass-bottomed boats and semi-submarines, to a descent into an underwater observatory at the Townsville Reef HQ (for more information, click here), which claims the world’s largest coral reef aquarium. Equipped with just a mask, fins and snorkel you can get close to the underwater world, or you can take the plunge and go scuba diving for the best encounters. If you’re not a qualified diver you can take a crash course at many resorts. Organised excursions for advanced divers are also readily available.

In some places the coral stands exposed, but visitors are asked not to walk over it, as doing so severely damages the living organisms.

Island types

Not all of the reef’s islands are made of coral. In fact, most of the popular resort islands are the tips of offshore mountains. True coral cays are smaller, flatter and more fragile.

The Reef Islands

The reef – actually a formation of thousands of neighbouring clumps of reefs – runs close to shore in the north of Queensland but slants further out to sea as it extends southwards. Hundreds of islands are scattered across the protected waters between the coral barrier and the mainland. Several have been developed into resorts, ranging from spartan to sybaritic, but not all are on the reef itself. Following are some details about these resorts, heading from south to north:

Fraser Island is actually south of the Great Barrier Reef, but it’s close enough and sufficiently interesting to rate inclusion here. About 120km (75 miles) long, Fraser is the largest sand island in the world, and a World Heritage site. Attractions include crystal-clear streams, lakes for swimming and rainforest trails. This is an unspoilt island for fishing, beachcombing and four-wheel-drive adventures, but not for sea swimming or coral dives (thanks to nasty rip tides and aggressive sharks). You can take excursions and flights to the island from Hervey Bay, or overnight at resorts, lodges, cabins or campsites.

Lady Elliot Island (www.ladyelliot.com.au) is a coral isle and part of the reef, but is situated south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Activities centre on diving, swimming and windsurfing. The gateway airport is in Bundaberg, a sugar-producing town 375km (233 miles) up the coast from Brisbane, and day-trip flights include use of the island’s resort.

Heron Island (www.heronisland.com), a small coral island right on the Great Barrier Reef, is heaven for divers. Nature-lovers can see giant green turtles, which waddle ashore between mid-October and March to bury their eggs in the sand. Heron Island also hosts thousands of migrating noddy terns and shearwaters. A resort on the island accommodates up to 250 people. There are no day trips and no camping.

Great Keppel Island (www.greatkeppel.com.au) is one of the larger resort islands, both in area and in tourist population (there’s even a backpackers). The Great Barrier Reef is 70km (44 miles) away, but Great Keppel is surrounded by coral, and there’s an underwater observatory. Its white beaches are among the best in the resort islands. Great Keppel is also one of the cheapest islands to reach from the mainland – a return ferry trip from Rosslyn Bay costs around A$50. For other angles on the island’s treasures, rent a sailboard, catamaran, motorboat and/or snorkelling gear, or try water-skiing or parasailing.

Brampton Island (www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/parks/brampton-islands), is reached by sea from Mackay, however the resort has been closed for some years (rumours of a reopening are rife). With forested mountains and abundant wildlife, the island’s mountainous interior is worth seeing, but access is hard unless you have your own boat. There’s a small campsite on neighbouring Carlisle Island, which is uninhabited and connected to Brampton by a reef that is wade-able when the tide’s out.

For a taste of paradise try one of the Whitsunday islands

Peter Stuckings/Apa Publications