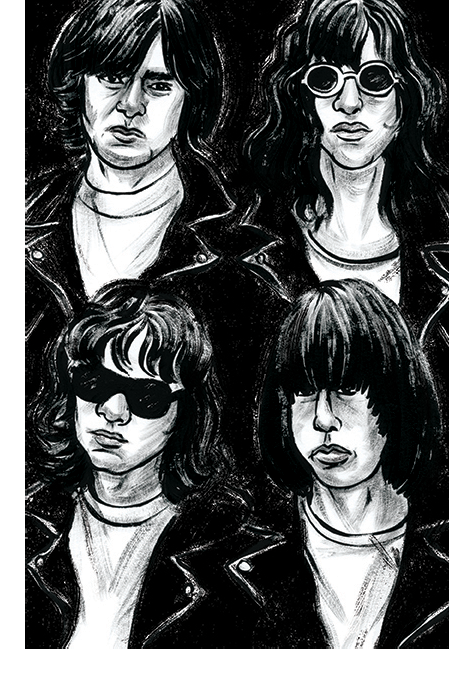

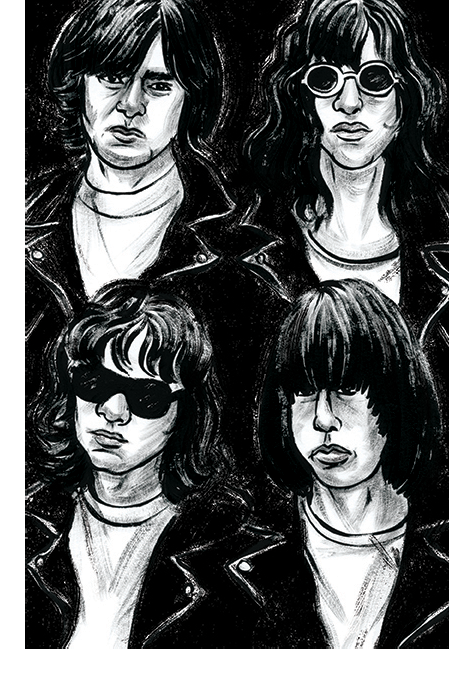

The Ramones

Any fool may write a most valuable book by chance, if he will only tell us what he heard and saw with veracity.

—Thomas Gray

I always liked loud music—the Stooges; Hendrix; early, crunchy Crazy Horse—but it wasn’t until I hit thirty that loud and fast and catchy—that alluringly cacophonous combination of sound that the Ramones virtually invented—began to make sense. Young and resolute and oozing adolescent energy I didn’t know what to do with, why would I want an accompanying soundtrack of driving frenzy blaring in my ears? But older and slower and every year wearier than the last, an aural pick-me-up began to have its appeal. Take two minutes of this and Hey-Ho-Let’s-Go call me in the morning.

Reducing the powerful attraction of the Ramones’ peerless music to its motivational utility, however, is as crude a critical diminishment as claiming to enjoy sex because it’s good for your cardiovascular system. Energy can be intoxicating; energy as an end in itself is empty and ultimately unfulfilling, an open tab at an abandoned bar with all of the lights left on. The music of the Ramones makes you move and makes you laugh and makes you sing and makes you remember what’s so wonderful about real rock and roll: it’s a ferocious reminder that we’re alive. The Ramones are also an example of the alchemical (and frequently inflammatory) constitution of all significant art and a lesson in the limits of limitation.

Before any of that, though, they were just four bored guys from the Queens, New York, suburb of Forest Hills, whose greatest ambition in life was to avoid having to get a real job. Before he became himself, Joey Ramone was Jeffrey Hyman, another kid from another broken home with the added burden of being too tall and too skinny and with bad eyesight and burgeoning obsessive-compulsive disorder, and whose lifeline was a transistor radio and a shitty stereo in the basement rec room. The Who and the Kinks and the Beach Boys and the Stooges weren’t entertainment—they were medicine.

John Cummings couldn’t have been any different from his future fellow Ramone—Johnny liked baseball and to steal things and to beat people up who wouldn’t do what he wanted. His musical epiphany was seeing Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1957, but more than anything else he wanted to be a New York Yankee. He liked the British Invasion bands enough to get a guitar, but couldn’t figure out how to play it sufficiently well, so he decided to quit when it got too hard.

Like Joey’s, Doug Colvin’s parents divorced when he was young, but the boy who would grow up to become boy-man Dee Dee Ramone never did anything in half-measures, not even family dysfunction. His alcoholic master-sergeant father was thirty-eight years old when he married Dee Dee’s seventeen-year old mother; Dee Dee was born in Virginia but grew up on a series of German army bases for the first fourteen years of his life; his favourite childhood occupation was searching old battle sites for Nazi artifacts to sell to American soldiers. (Occasionally—as when he discovered several tubes of morphine—he kept the loot for himself.) It was while his father was briefly stationed back in the US that Dee Dee heard rock and roll loud and clear for the first time, while buying potato chips at the PX Snack Bar in Atlanta.

The oldest of the original Ramones, Tommy Erdelyi, aka Tommy Ramone, was born in 1949 and moved to America with his family from Hungary when he was seven. He was also the (relatively) normal one—worked in a recording studio in New York after high school and liked to watch foreign films at the MoMA during lunch breaks and played in a handful of third-rate glam and hard-rock bands. In such a relatively insular suburban community, it’s not surprising that the four knew each other. (Who else would want to know them?) All in all, four Forest Hill fuck-ups who helped save rock and roll. It’s really that simple; it’s really that confounding.

Obviously, there were influences. The Stooges’ bass, drums, and guitar greaseball assault and disarmingly honest lyrics (about being bored, being apathetic, being bugged by other people); the MC5’s full-on metallic ferocity; the Beatles’ masterful melodicism; sixties girl group sha-la-la’s; the sunny pop pleasures of early, surfboarding Beach Boys; the local live example of the decked-out, drugged-out New York Dolls, clearly having—gasp!—a ball up on stage, something the oh-so-serious music industry of 1973 frowned upon as puerile and unprofessional; an unapologetic love of popular culture, from comic books to horror movies to the shlockiest television programs to the most disposable of bubblegum music. But other people, other bands, had similar enthusiasms and inspirations, yet none of them ended up making the music that the Ramones did. The short version is that the Ramones were more than the sum of their parts. Without the inimitable, intensely personal contribution of even one of the four, the group’s pioneering music wouldn’t exist as we know it.

The Beatles were one of Johnny’s favourite bands, which would account for why he went to see them perform live when they came to New York. Johnny’s teenage friend Richard Adler explains—or, rather, describes—what happened after that: “Once we all went to see the Beatles at Shea Stadium and John brought a bag of rocks and threw them at the Beatles all night. It’s amazing nobody got hurt. These were rocks as big as baseballs.” Without Johnny’s unrelenting annoyance—at life? himself? both?—the Ramones wouldn’t have played at such a wonderfully ridiculous speed or with such bracing aggression right from their inaugural rehearsal (well, not the first rehearsal, when they couldn’t play their instruments well enough to do much more than try to stay in tune). Because of Joey and Dee Dee and Tommy, though, who wrote the lyrics and arranged the tunes, the songs never soured into emptily angry diatribes. Instead, they were suffused with twisted humour and affirmative vitality and married to enriching melodies. Rage can be cleansing and even (briefly) constructive; indulged in exclusively, however, it can also be a gateway emotion to a purposeless pit of self-pity. The Ramones meant it, man, but unlike, say, welfare-state whiners like the Sex Pistols, their music still means it; cozily ensconced in California cupidity, John Lydon isn’t thinking about anarchy in the UK when he drives down the freeway on the way to his favourite sushi restaurant. Joey, on the other hand, lived for beating boredom and having fun and making the best out of the worst that life can come up with right until the end. (What was the title of his posthumous solo album, which he worked on throughout his long struggle with cancer? Don’t Worry About Me. What was its most affecting song? A cover of “What a Wonderful World.”)

Even the Ramones’ respective members’ individual strengths and (mostly) weaknesses as neophyte musicians contributed to the band’s immensely inventive sound. Yes, you can hear the brutally repetitious attack of Led Zeppelin’s “Communication Breakdown” and Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” in Johnny’s signature buzz-saw guitar style. And, yes, Johnny was on record as saying he hated the turn rock and roll had taken toward instrumental virtuosity and prolonged, self-indulgent soloing, though the fact that he played downstroke barre chords almost exclusively suggests necessity more than conscious innovation. (The Ramones always got outside musicians to play whatever short guitar solos were necessary on their records simply because Johnny wasn’t capable of doing them as well.) And this was no chic faux-primitivism, either. Flamin’ Groovies front man Chris Wilson remembered a telling hotel-room encounter: “I passed my guitar to John and said, ‘Have a go,’ and he went, ‘I’m sorry, man. I only know how to play bar-chords.’” Also, Johnny—who was the band’s central image maker and the one who insisted that they all wear the black-leather-jacket-and-torn-blue-jeans uniform (although it was Dee Dee who took the surname “Ramone” for himself after learning that “Paul Ramon” was Paul McCartney’s pseudonym, and who convinced the other band members to adopt it as a sign of unity)—admitted he simply liked the way he looked in the mirror with the guitar slung low over his shoulder, like a gunslinger, which made any technique but the downstroke nearly impossible to pull off.

Perhaps because he was the least intriguingly scandalous of the original four Ramones (meaning: he wasn’t a drug addict, mentally ill, or psychotic), Tommy tends to get short shrifted for his enormous contribution to the band’s sound, not least by the other band members themselves (in the excellent documentary, End of the Century, for example). Even more than Johnny, who had at least played a guitar before beginning to practice in earnest when the Ramones formed in 1974, Tommy approached his instrument with few preconceptions, never having even played the drums before, and only took over behind the kit because none of the drummers that the novice band auditioned was right for the group, most being heavy-metal bashers in the manner of the day. In the end, the anti-style he developed—essential to the group’s musical aesthetic, yet minimal to the point of being utterly subservient to the song; metronome-steady yet neck-and-neck fast with Johnny’s furious downstroking—became an estimable, much-imitated style. Thoroughly utilitarian and instantly identifiable: a hard trick to pull off, but one made easier, ironically, by Tommy’s inexperience. As Rolling Stone writer and Ramones fan David Fricke pointed out, “Tommy was able to unite the others over his backbeat, which you’d think anybody could have done . . . [But] Tommy play[ed] at the same speed, the same beat, the same patterns all the way through. Most drummers are genetically incapable of doing that. He knew that simplicity was king.” He also didn’t know any other way to do it, which meant simplicity was also a necessity.

Rock-and-roll songs usually have words as well as music, though, and the Ramones’ lyrics were no less forged from their ostensible shortcomings as their sound. Unless you count comic books or Mad magazine, none of the Ramones were what you’d call big readers. Which means that entire songs sometimes consist of only a few lines of words, resulting in repetition to a compulsively hypnotic, almost rhythmic degree. Which also means that while the band wasn’t capable of something in the lyrical league of “Suzanne” or “Like a Rolling Stone,” they also weren’t going to concoct a piece of pseudo-profundity like “Celebration of the Lizard” or “Stairway to Heaven.” A little bit of education can go a long way toward a lot of bad art. More than just safeguarding them against avant-garbage tendencies, however, the Ramones’ genius lay in honestly embracing what they really did know and care about, rather than feigning interest in what they were supposed to find important. Fellow musician Richard Hell was among the first to recognize this:

All their songs were two minutes long, and I asked them the names of all their songs. They had maybe five or six at the time: “I Don’t Wanna Go Down to the Basement,” “I Don’t Wanna Walk Around with You,” “I Don’t Wanna Be Learned, I Don’t Wanna Be Tamed,” and “I Don’t Wanna” something else. And Dee Dee said, “We didn’t write a positive song until “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue.” They were just perfect, you know?

Perfect because they played short songs because they found long songs boring; perfect because they preferred Night of the Living Dead to Long Day’s Journey Into Night and didn’t need a French literary theorist to say it was okay; perfect not just because they were honest—after all, Jim Morrison honestly believed he was a poet—but because, by celebrating their sincerest passions in song, they consecrated those passions, art’s highest function.

Joey, the one who sang the words to the songs, was the human embodiment of wringing eventual victory from seeming failure, the ultimate DIY success story. Contra Mick Jagger, the archetypal cock-strutting lead singer of the era, Joey was (at least early on) clearly emotionally insecure and physically awkward up on stage, a black-clad praying mantis with self-esteem issues (he’d been kicked out of his previous band not for his singing ability, but because he wasn’t good looking). He was also the sum of his LPs, his record collection’s collective unconscious, and his accent when singing was part New York, part British, part entirely unpersuasive bravado, a self-fabricated verbal mishmash of whoever he wanted to be—and, in time, he was, at least come show time. He was, in other words, any one of the band’s audience members, the daydreaming outcast who somehow ended up with the microphone in his hand.

Eyewitness accounts of the band’s first shows are illuminating. There’s virtually no ambivalence: it was either instant adoration or incredulous dismissal. Performing at CBGB—the now-legendary spawning ground of American Punk, then-Bowery cesspool with a liquor license—the audiences were sparse and the reaction intense. Punk magazine co-founder Legs McNeil: “It looked like the SS had just walked in, they [the Ramones] looked so striking. I mean, these guys were not hippies, this was something completely new. And the noise of it was . . . it just hit you.” Blondie bassist Gary Valentine:

Until I saw the Ramones play, I thought the Dolls were the loudest band ever. They were fantastic, 20 songs in 15 minutes, one after the other, one minute, two minute songs. There was this tacit, pent-up notion of violence in the background, but on stage they were a lot of fun, in a Saturday morning cartoon, “Hey hey we’re the Ramones” way. Even though the songs were different they all sounded the same—it was like Beethoven over one-and-a-half minutes, with Joey Ramone mumbling over the top.

Legendary scene-maker and music journalist Danny Fields, whom Tommy, the group’s de facto leader, had been pleading with over the phone to come and see their show, reluctantly attended one of the band’s gigs at CBGB and came away so impressed he immediately offered to be the band’s manager:

The Ramones had everything I liked. The songs were short. You knew what was happening within five seconds. You didn’t have to analyze and/or determine what it was you were hearing or seeing. It was all there, and every aspect of what they were doing was excellent, from the clothes to the posture to the lyrics. Everything. It was excellent. It was the sound that got me. I thought the music of the Ramones was pretty much dealing with everything that the world needed then. You know, fill up that syringe and here’s my arm. Give it to me! Shoot it!

On the other hand, Mark Bell, later Marky Ramone when he took over from Tommy behind the drums, had a different initial impression: “When I first saw them at CBs I thought they sucked because there were no fills, no drum rolls because that’s what I’d been doing all my life.” Monte Melnick, who would go on to be the Ramones road manager for over twenty years, couldn’t quite believe what he was seeing: “I watched them and it was like I was laughing, you know? Because I was more a serious musician, you know? And watching the Ramones was like a joke, really.”

Danish physicist Niels Bohr famously stated that, “When the great innovation appears, it will almost certainly be in a muddled, incomplete, and confusing form. To the discoverer himself it will be only half-understood; to everybody else it will be a mystery. For any speculation which does not at first glance look crazy, there is no hope.” When Alan Vega of the band Suicide told Johnny he thought the Ramones were fantastic, that they were just what rock and roll needed, Johnny’s first thought was, This guy’s crazy. He later told Dee Dee that if they could fool Vega, maybe they could fool more people.

After hearing enough people say the same thing, though, and after enough gigging and seeing the audiences at CBGB grow from twenty or so friends and fanatics to three-hundred-and-fifty people a night, the band’s confidence grew to the point that they saw their mission as nothing less than messianic. Craig Leon, who produced their first record with Tommy’s assistance after the band had signed to Sire Records, remembered:

Hell, I thought they were going to be massive off their first record and so did they. They were thinking they were in like the Beatles, Herman’s Hermits territory, not any kind of underground Stooges/performance-art damage. The Ramones thought they were going to revitalize pop music.

As impossibly naive as this sounds now—the Ramones, the quintessential cult band, aspiring toward mass acceptance—it’s one of the key reasons why the band’s eponymous 1976 debut remains so novel, so dynamic, so resounding: like all true eccentrics or creators of genuine “outsider” art, the Ramones sincerely believed that they were normal and that what they were doing was what everyone should be doing.

Ramones’ most famous song, for example, lead-off track “Blitzkrieg Bop,” was written partly because Dee Dee was an irony-free Bay City Rollers fanatic. Play them one after the other and it’s obvious that “Blitzkrieg Bop”’s signature “Hey Ho Let’s Go” chant is simply the Ramones’ version of the Rollers’ “S-A-T-U-R-D-A-Y Night” chant. Of course, as peppy and catchy as, say “Saturday Night” is, because it was intended exclusively to sell in large numbers to homogenous hordes of suburban teenage girls, there’s not much beyond that peppiness and catchiness to recommended it. “Blitzkrieg Bop,” on the other hand, is informed not only by a belief in bubblegum music’s pure pop appeal, but generous dollops of raw energy, humour, and danger born of the band members’ other delightfully disparate loves/obsessions. Bubblegum tastes good and is fun to chew—until the flavour’s all gone and you get tired of chewing. “Blitzkrieg Bop” is as resilient as a rock and roll song gets because in 2:12 seconds it’s a nice fresh piece of Dubble Bubble dosed with a snort of cocaine, a whiff of laughing gas, and a bracing smack in the face.

Sire Records got thirteen more songs for the preposterously paltry $6,200 that the album cost to make (cf. the Sex Pistols lone album, the budget of which was well over $100,000 dollars—not bad for impoverished anarchists). “Beat on the Brat” is about exactly what it sounds like, immediately raising the question of just how much these guys were joking around. Beating up obnoxious neighbourhood rich kids with a baseball bat—sure, we’ve all secretly wanted to do it, but Joey isn’t really singing that we should, is he? Is he? Ditto for “Loudmouth,” as pre- a PC-relationship song as there is. “I Don’t Want to Go Down to the Basement” feeds off phobias directly inspired by slasher films, while “Chain Saw” is an ear-splitting tribute to a very specific film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. “I Don’t Wanna Walk Around With You” and “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue” perfectly encapsulate yin and yang as they exist in the Ramones’ universe. “Today Your Love/Tomorrow the World” uses—gulp—a Nazi metaphor for conquering true love, while in “53rd & 3rd” a male street hustler who feels bad when he doesn’t get picked by the assembled johns and then repulsed by himself once he does, decides that the only way he can maintain his dignity is by stabbing his trick to death. Proving that life isn’t all aggravation and bewilderment occasionally punctuated by a sniff of airplane glue, there’s “I Wanna be Your Boyfriend,” a sweet, almost chiming reminder that’s there’s unrequited love to look forward to as well. And the album’s sole cover—an amped-up, sped-up, Ramones-ized version of the early sixties Chris Montez hit “Let’s Dance”—serves to remind everyone what the whole thing (the Ramones, the album, existence) is really all about. Fourteen songs in twenty-eight minutes, fifty-three seconds, and if at the end of side two you’re as emotionally and intellectually off balance as if you’d been physically and psychologically pummeled, that’s all right. That’s what art is supposed to do.

After being welcomed as conquering heroes in England, it was back to playing for fifty people in the US, unless the venue was on home turf Manhattan. It didn’t help that radio wouldn’t have much to do with them either. Session-man Andy Paley, who worked with the Ramones on the Rock ‘N’ Roll High School movie:

The Ramones didn’t stand a chance. It wasn’t so much their image as their sound—as much as I thought they were fun, the radio people didn’t. Radio hasn’t been very good in America for a long, long time. Originally, in the Fifties and early Sixties, you’d have great regional DJs in different towns, but it got worse and worse, and then . . . FM radio took over, and it got turned into a . . .corporate thing.

Any successful corporation eschews controversy—why risk offending a potential customer?—and by the time the band began recording their second album, Ramones Leave Home, the group had been lumped in with the nascent “punk rock” movement. In mainstream media terms, this meant safety pins stuck through filthy, unemployed people’s noses, the kind of people who spit at their favourite performers on stage and who, in general, acted like murderous lunatics. That the media image of the proto-punker was taken primarily from the British scene, where fashion and violence seemed to be some sort of dual statement against an unjust society (or something) and that the Ramones basically considered themselves just a plain old contemporary rock and roll band didn’t much matter. Add to the mix four very . . . unique individuals traveling in a small van several hundred miles every day to play before less than a hundred people (if they were lucky), and you’ve got a recipe for incipient disillusionment, infighting, and mental strain.

Even if the Ramones had been flying first class to sold-out stadiums full of adoring fans there would have been trouble. Here’s Chris Frantz, the Talking Heads drummer, whose band opened up for the Ramones in Europe:

The first indication to me that Johnny Ramone was weird was on that first European tour. We flew to Switzerland and we went right to the sound check. After that we went to a little café, and the services promoter ordered us a beautiful caprese—a really nice salad, with mozzarella cheese, tomato, and delicious, high quality lettuce. Johnny said, “What’s this?! You call this lettuce?!” Johnny was actually upset that the lettuce wasn’t iceberg lettuce . . . [Later on] we went to Stonehenge and Johnny stayed in the van. [And insisted that his girlfriend also stay, even though she wanted to join the others.] He’d snarl, “I DON’T WANT TO STOP HERE. IT’S JUST A BUNCH OF ROCKS!”

Mickey Leigh, Joey Ramones’ brother, who briefly roadied for the band before quitting to pursue his own musical career, recalled having to list his occupation on an immigration form at the airport:

as a gesture of good luck and omen for the future, I wrote “musician.” When Johnny saw it, he freaked. “Whaddaya puttin’ that in there for?” he screamed at me. “You’re not a musician! You’re not a professional!” . . . It was John getting his jollies humiliating someone. What else was new?

Tommy remembered how

[w]e got known as the group who would punch each other out on stage, but there were only a couple of instances where that actually occurred. Mostly John would just give people very dirty looks. He perfected that as one of his psychological weapons. It was effective because you knew what was behind it. John always prided himself on his control, but he had a very short temper. You could see it in his eyes. Johnny was scary.

Monte Melnick, who travelled with the band for twenty-two years, was more succinct: “He was Mr. Negative. He was a very controlling person who radiated fear and anxiety.”

Dee Dee wasn’t interested in dominating anyone—he just wanted to do the opposite of everything Johnny, the band’s self-appointed overseer, demanded. (“We used to call them the Marones because Johnny was such a drill sergeant,” Dead Boys’ guitarist Cheetah Chrome remembered. “They’re not the Marines—they’re the Marones.”) Melnick: Dee Dee’s “first wife Vera Davie said that he was diagnosed as being bipolar. It didn’t help that he did drugs constantly. He started doing drugs when he was young, so who knows if it was chemical or not. I’m sure he definitely had a split personality and who knows what that does to your internal chemistry.” Vera Davie: “I had no idea what each day would be like and would be cautious to even speak in the morning when he got up. You never knew which Dee Dee you were getting . . . I walked on eggshells every morning until he decided the mood of the day and who would be his victim.” Photographer Bob Gruen: “He used to walk around without a shirt on in the middle of the night carrying a baseball bat.”

Joey came by his instability naturally—it wasn’t enough to be freakishly tall, skinny, and myopic (his childhood nickname was “Geoffrey Giraffe”), he also suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder to a frequently debilitating degree. Melnick: “We had a central meeting place when we’d leave on a van trip, in front of Joey’s apartment house on East 9th Street in the East Village. Whatever time I told Joey we had to leave, I’d tell the band an hour later because that’s how long it would take him to get ready and touch everything. It was hell getting him in the van.” Booking agent John Giddings: “He’d get in and out of the elevator ten times before he’d actually go anywhere. There was a weird moment in Spain where Joey couldn’t decide when to cross the road. He got off the curb, got back on the curb, got off the curb and so on, until this car was so bored waiting, it hit him.”

Tommy was suffering from plenty of weird moments himself, mostly because he was often stuck inside a van with Johnny, Dee Dee, and Joey. He’d been the one with the original vision to encourage Dee Dee and Johnny to start a band because he thought they were such compelling personalities; to move Joey from behind the drum kit to centre stage because he recognized Joey’s potential as both a singer and an arresting, unorthodox front man; who’d been instrumental in helping to transfer the band’s live sound and ideas onto tape in the studio—being a touring drummer playing one-nighters across America was never his ambition. Several members of the Ramones’ circle remember him relying on valium when they toured and being so consistently anxious his hands shook.

Still, Ramones Leave Home was recorded and released a mere six months after the band’s debut, mainly because they’d written approximately thirty songs before they even had a recording contract and then decided to record them all in the order they were written. Just like in the song, second verse same as the first: more songs about mental illness (“Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment”); chemical self-abuse (“Carbona Not Glue”); anti-love songs (“Glad to See You Go” and “You’re Gonna Kill Girl”); tender love songs (“I Remember You” and “And I Love Her So”); Nazi piss-takes (“Commado”); horror-movie homage (“You Should Never Have Opened That Door”); outsider anthem (“Pinhead”); and another perfect (i.e., fun, fast, and sincerely frivolous) cover song (“California Sun”). Because they had more time and money the second go around, Ramones Leave Home sounds more obviously produced than the first album, but only in that the snarl and bite of the songs is more pronounced, the slightly higher production values only accenting the lyrical sleaze and musical sparkle. Tommy co-produced the album with Tony Bongiovi, who couldn’t help wondering if it was going to be one “of the biggest things ever done or one of the greatest flops.” As with all seminal art, ambivalence wasn’t an option.

Then it was back in the van, back on the road, back to sometimes being heroes (future Dead Kennedy’s singer Jello Biafra: “[T]he Ramones mowed down everybody in the room. It totally blew me away, in part because I kept turning around and seeing the looks of shock and horror on people’s faces, them going, ‘No, no! Make them stop!’ and I’m going, ‘Yes, yes! More, more’”); sometimes being villains (opening for Black Sabbath for example; Arturo Vega, the band’s graphic designer and artistic director: “The metal fans were by far the majority of the crowd, so they came ready to kill—and they tried, aiming at the band with cans full of beer. After six songs, the amps and the stage were all covered with garbage. That was scary, but it got worse”). Through it all—the commercial indifference, the sometimes-uncomprehending and often hostile audiences, the strain of living in each other’s smelly pockets—the Ramones pushed on, secure in their mission, at least, and fortified by their street-rat resilience. Arturo remembers the band playing “in Manchester, in some school, and Dee Dee must have been doing drugs that day—or maybe he did them right before they went on stage. So Dee Dee’s playing and he’s getting sick. So he goes to the side of the stage and vomits. And he never stops playing!” Even Johnny, who would fine band members for being late for soundcheck or for drinking before the show, had to have been impressed.

By now, as Joey’s brother recounted,

the Ramones didn’t socialize with each other anymore. Johnny rarely left his house if they weren’t playing. Dee Dee spent more time with Johnny Thunders, or anyone else with dope or pills. Tommy was more than happy to be in the studio . . . [And] Joey still needed a lot of care . . . [His girlfriend] Robin tried to keep him clean and healthy.

None of which stopped them from writing a new batch of songs and recording their third classic LP in a row, 1977’s Rocket to Russia. Although there were some Ramones firsts—“Here Today, Gone Tomorrow” is downright tender; there are two cover songs this time (“Do You Wanna Dance?” and “Surfin’ Bird,” both of which are so respectively infectiously joyful and goofy that they sound as if they could have been written for the band); there’s even a (short) guitar solo—Rocket to Russia is almost a duplicate of the first two albums, which makes its aesthetic success more than a little surprising. More songs about mental illness, personal dysfunction, and rock and roll as liberation? How many times can these guys go to the well and come up with a brimming bucketful? At least once more, anyway. And all because the songs were great, the production polished but punchy, and Joey never sang better. “Teenage Lobotomy” would be terrifying if it weren’t hilarious; ditto for “We’re a Happy Family,” the one where everybody in the clan is on Thorazine and daddy secretly likes men; “Sheena is a Punk Rocker” is feminism for everyone; and “Rockaway Beach” is pure Ramones, celebrating something lousy until it becomes something sacred (if only in your mind). Live, the Ramones played so loud and fast it was almost impossible for Joey to shout out the words quickly enough; on record, though (at least on the first five albums), you heard what an increasingly effective instrument his voice had become, capable of adolescent yearning, ironic hilarity, and pissed-off nihilism from one song to the next.

Although “Sheena” garnered the band their first serious airplay (getting as high as number thirty-six in the UK, where the Ramones were initially a much bigger deal—the 1979 live album It’s Alive was recorded in Britain and, for many years, released there only), the band still wasn’t selling enough records to lift them out of the exhausting club circuit. It was at this time that Tommy told the others he was quitting the band, but would stay on to help write songs and produce the albums. First they tried to talk him out of it; later on they dismissed him as not being a “real Ramone,” someone who couldn’t hack life on the road. All of the original Ramones died relatively young, but Tommy outlasted the other three by many years, so draw your own conclusions. In the end, when Marc Bell, late of Richard Hell’s the Voidoids, became Marky Ramone, the band definitely got a “real” Ramone. Arturo:

Marky is the character that goes out in the backyard, plays, gets itself all muddy and dirty, comes into the living room and shakes itself out and gets everybody in the family and the furniture dirty. You wanna kill him but you don’t—he’s your pet, that’s what pets do.

Tommy could teach Marky, already a fine musician, his signature Ramones drum style, but he couldn’t instruct him in how to be a human buffer zone between feuding bandmates or how to be a calming presence in the van or in the hotel or sometimes even on stage.

Road to Ruin, the initial album recorded with Marky behind the drums, was the first indication that the band was in trouble artistically. Whereas the first three albums were released within a sixteen-month period, Road to Ruin didn’t appear until nine months after Rocket to Russia hit the shops. The Ramones weren’t the kind of band that benefited from a long gestation period and a protracted recording schedule. Instinct eschews prudence.

Ironically, it wasn’t the band’s attempt to make a more commercial record that was Road to Ruin’s major flaw. Engineer Ed Stasium admitted that “We [the band] came to a decision that Tommy and I would try different bass and guitar parts—keep what the Ramones were, but appeal to a broader audience,” and for the most part the tinkering was creatively rewarding. The introduction of acoustic guitars into the band’s sound works surprisingly well, particularly on the album’s first single, “Don’t Come Close.” For some reason, both Legs McNeil in his notes to the expanded CD reissue of Road to Ruin and Everett True in his normally reliable and highly informative biography of the band, Hey Ho Let’s Go, dismiss “Don’t Come Close” as a “country and western tune,” a bizarre categorization. The Ramones never disguised their love of bubblegum and other atypical “punk rock” influences, and “Don’t Come Close” is an admirably catchy power-pop confection that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on an early Todd Rundgren album. Maybe Johnny reportedly hated it so much because there was no way he could have played the cascading acoustic guitar runs that anchor the song. On the album’s sole cover, a version of the Searchers’ 1964 hit “Needles and Pins,” and on the unabashedly vulnerable ballad “Questioningly,” Joey’s voice—and not Johnny’s guitar—is the lead instrument, variations of intonation subtly enriching the band’s trademark sound. The album’s one undisputable classic is the chugging “I Wanna be Sedated,” another tale of mental illness made palatable by the usual laugh-aloud lyrics and winning melody, but also by an uncharacteristically bouncy rhythm, happy happy hand claps, and some refreshing light/shade guitar interplay.

And that’s about it. For the first time on a Ramones record, the majority of the songs sounded . . . stale. Trying to sound primitive never sounds authentically primitive. No matter how much Tommy and Stasium augmented the group’s playing, the riffs and melodies were becoming predictable, the lyrics barely concealed rewrites of previous songs. If titles like “I Just Want to Have Something to Do,” “I Don’t Want You,” “I’m Against It,” “Go Mental,” and “Bad Brain” sound disappointingly familiar, that’s because they are. You can—as the Ramones did—reenergize rock and roll and even create an entirely new sub-genre, but popular music is still all about the songs, and Road to Ruin simply doesn’t have nearly enough good ones. The last tune on the album is “It’s a Long Way Back.” The title doesn’t refer to the band’s increasing loss of inspiration and inability to recapture their initial primality—it’s just one more number about Dee Dee and Germany—but it might as well have.

Because, once more, an album of theirs didn’t sell—an album that was constructed to sell—the band became even more fixated on commercial success. Which is why they agreed to appear and perform in schlock-auteur Roger Corman’s Rock ‘N’ Roll High School. Why the Ramones thought appearing in a cheesy B-film would give them mainstream credibility is hard to comprehend. But desperate people do desperate things. The pay for their participation in the movie was so poor that they had to play gigs around Los Angeles on off-days to remain solvent. Performing regularly in LA clubs did have one significant impact on the band’s career: bowing to record company pressure to let an experienced producer oversee their next album in a bid for commercial pay dirt, they agreed, after getting to know him better, to Sire’s desire to have Phil Spector produce what became End of the Century. Spector had been a fan of theirs for a couple of years. (“Phil just loved their music,” veteran Spector session-man David Kessel recalled. “It was like, ‘God, you mean there’s a rock-and-roll band around?’ The simplicity of the chords; the lack of improvisation. He thought that it was right back to Buddy Holly.”) The album’s title was apt. End of the Century is the Ramones’ last essential record, it was the last meaningful work Spector ever did, and what little genuine band dynamic was left evaporated when, around this same time, Joey’s girlfriend left him for Johnny.

In 1979 Phil Spector was, yes, still a legend in the recording industry, but he was living on not just past royalties but past successes, was an increasingly forgotten, bitter little man with a toupee on his head, lifts in his shoes, and an unearned sense of artistic entitlement. His behaviour during the recording of the album is much more interesting than the actual work he did on it. Vera Davie:

Phil never came to greet us at the entrance [of his baronial house]. Instead, as we entered the main living quarters, we saw and were greeted by Grandpa Munster himself, Al Lewis, sitting in a big chair with a high back . . . Lewis was very friendly, but it was obvious he had been sitting there for quite a while, because he was pretty much intoxicated by the time we arrived. We waited with Lewis for at least an hour before Phil made his grand entrance and bestowed us with his presence. Soon after we were led into his private recording studio where he blasted all of his hits for us over and over again . . . After listening attentively to Phil’s albums, he decided we should all watch his new favorite movie, Magic, starring Anthony Hopkins. We watched as Phil rewound his favorite parts and showed the movie again and again, just like he did with his songs. By this time it was six o’clock in the morning, and Dee and I were exhausted. Johnny had somehow managed to leave around midnight, but Dee and I had to beg and plead with Phil to let us go home . . . We couldn’t just leave and walk out the door because we had to be electronically buzzed out; it was up to Phil to let us leave.

It’s not surprising that Johnny didn’t wait for Spector’s permission to go home—Johnny gave orders, he didn’t take them—just as it wasn’t surprising that he chafed under Spector’s dictatorial production technique. Stasium:

The sessions were grueling, especially for Johnny, who hated Phil. Joey loved Phil [and vice versa]. We were there for hours and Johnny got fed up doing take after take after take. I have a little diary and he played “This Ain’t Havana” back like 353 times. Over and over at absurd volumes. Of course, we’d start at 10 p.m. for these sessions, which was ridiculous. The final blow was the infamous “Rock ‘N’ Roll High School” intro. Johnny made it sound like eight hours we were there, but it was probably more like two hours. But it was a helluva long time playing one chord.

After Johnny threatened to quit the sessions and Spector promised to tone things down a bit (which really meant drinking less in the studio), the album was completed and the mixes were given the legendary Spector production treatment and the result was . . . okay. (And ended up selling just okay as well; it was certainly the band’s best-selling album, but nothing like the top-ten monster they thought they’d created. At $200,000, it was by far the costliest Ramones LP to make.) It would have helped if it hadn’t contained such formulaic fluff as “Let’s Go” and “All the Way” and the embarrassingly self-referential “The Return of Jackie and Judy.” Still, opening track “Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio?” was a rousing success, the characteristic Spector production touches (organ, saxophones, a booming drum sound) expertly complementing the Ramones’ raging tribute to the redemptive power of rock and roll. “Rock ‘N’ Roll High School” was an ideal tune for Spector to work on—beefed up, Doo-Wop-influenced fifties rock and roll—that’s as furiously fun as it is enjoyably idiotic. Spector was used to working with singers, not bands, and part of Johnny’s resentment toward the producer was undoubtedly born of jealousy over the disproportionate amount of attention Joey received in the studio (Spector had originally wanted to record a Joey solo album). Whatever discord this created within the band, however, was justified by the wonderful vocal performances Spector got out of the Ramones’ singer. “I Can’t Make it on Time” is Joey at his power-pop belting best, the string-drenched cover of “Baby I Love You” isn’t really a Ramones song (none of them play on it), but Joey, the rock-history worshipper, is plainly glorying in being a vocal stylist for once à la one of his heroes, Ronnie Spector, and “Danny Says” is simply a lovely love song.

“Danny Says” is about Linda Danielle, who was Joey’s girlfriend at the time it was recorded, and by the time End of the Century was completed Joey wasn’t the only one in love with her. People fall in love with people they shouldn’t fall in love with every day, so attempting to discern who was right and who was wrong in matters of the omnipotent, unreasonable heart is pointless. The bottom line is that Johnny and Linda fell in love with each other, Joey felt doubly betrayed, and the two band members were never friends again. It probably didn’t help that neither Johnny nor Linda ever talked to Joey about it. Joey’s brother Mickey:

Too many people around the Ramones would become noticeably quiet if Joey suddenly appeared. Were people laughing at him? Some probably were. That would have been consistent with Johnny and the Ramones’ philosophy: no sympathy, no apologies, and no display of sentiment or concern. For Johnny, any form of empathy was for hippies and wimps.

In fact, except for absolutely unavoidable Yes’s and No’s, Joey and Johnny didn’t speak to each other for the next sixteen years, including in the increasingly claustrophobic van (roadie George Tabb: “Monte [Melnick] was a translator between Johnny and Joey, which was kinda funny because they were next to each other. They would literally talk through him”). They forced themselves into that van for sixteen more years because, as Melnick pointed out, “The friendship died after the Linda incident, yet they carried on for the sake of the band like a couple staying together for the children.”

Except that sometimes a clean break is better for all concerned. To Johnny’s credit, he later admitted that if he’d been able to financially afford it, he would have retired his guitar after End of the Century, by which time he knew that the band was never going to have any substantial impact on mainstream culture and that they’d clearly peaked creatively (and that what were once close comrades were now barely tolerated workmates). For nine more decreasingly relevant studio albums released over the next decade and a half, however, Joey kept the faith, hoping, each time out, for the elusive hit that would elevate them to the commercial heights achieved by some of their one-time opening acts such as Blondie and the Talking Heads. (Not because of the money, but because he thought the Ramones were the greatest rock and roll band in the world and justifiably wanted the greatest number of people to know it. It’s easy to retrospectively counsel the dead on how they should have acted tranquilly and untroubled while alive, but the idea of hearing “Blitzkrieg Bop” routinely played at hockey games was unfathomable when the band was still around, and very few real artists get to live as legends, confident in their lasting creative worth.)

Live, the Ramones never let their fans down, not even when Dee Dee quit the band in 1988 because he was tired of being a middle-aged juvenile delinquent, and they hired a Dee Dee clone to yell “1-2-3-4!” before every song. But between Johnny’s emotional resignation, Joey’s continuing disappointment, and Dee Dee’s desertion, the individual Ramones grew to be not very happy people. And these were never particularly well-adjusted individuals to begin with.

By the time Joey died of lymphoma in 2001—abetted by an OCD-related broken hip, the treatment for which fatally impaired his cancer fight—the only Ramone to visit him in the hospital was Marky, despite the fact they’d been feuding on the Howard Stern show not long before. When Dee Dee died a little more than year later of a sadly inevitable heroin overdose, he hadn’t been an official Ramone for over a decade (even if he’d never managed to escape being Dee Dee Ramone). Typically, Johnny outlasted the other two, but only by a few years, the colon cancer that claimed the life of the non-smoking, virtually non-drinking guitar player probably caused as much by his searing, never-abated anger and aggression as it was by genetics. We tend to die the way we live.

Although all rational people can agree that such an institution should not exist, when the Ramones were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002, it was worthwhile if only for this: Dee Dee wouldn’t sit with Johnny; Johnny wouldn’t sit with the deceased Joey’s brother and sister; Marky told Joey’s brother about a rumour going around that Johnny wanted the rest of the band to turn their backs on him and his mother when they came up to accept Joey’s award. True or not, it didn’t matter—because of mismanagement on the part of the presenters, Joey’s trophy got left behind on stage. When someone finally handed his mother the award, she was understandably, if belatedly, pleased—until she discovered it had Dee Dee’s name on it. Elsewhere in the ballroom, Dee Dee realized he had Johnny’s award, while Johnny learned he had Joey’s. Ramones whether they wanted to be or not. Forever.