MARY made her public entry into the city of London, on the 3d of August, 1553. The most magnificent preparations were made for her arrival, and as the procession of the usurper—for such Jane was now universally termed,—to the Tower, had been remarkable for its pomp and splendour, it was determined, on the present occasion, to surpass it. The Queen’s entrance was arranged to take place at Aldgate, and the streets along which she was to pass were covered with fine gravel from thence to the Tower, and railed on either side. Within the rails stood the crafts of the city, in the dresses of their order; and at certain intervals were stationed the officers of the guard and their attendants, arrayed in velvet and silk, and having great staves in their hands to keep off the crowd.

Hung with rich arras, tapestry, carpets, and, in some instances, with cloths of tissue gold and velvet, the houses presented a gorgeous appearance. Every window was filled with richly-attired dames, while the roofs, walls, gables, and steeples, were crowded with curious spectators. The tower of the old church of Saint Botolph, the ancient walls of the city, westward as far as Bishopgate, and eastward to the Tower postern, were thronged with beholders. Every available position had its occupant. St. Catherine Coleman’s in Fenchurch Street—for it was decided that the royal train was to make a slight detour—Saint Dennis Backchurch; Saint Benedict’s; All Hallows, Lombard Street; in short, every church, as well as every other structure, was covered.

The Queen, who had passed the previous night at Bow, set forth at noon, and in less than an hour afterwards, loud acclamations, and still louder discharges of ordnance, announced her approach. The day was as magnificent as the spectacle—the sky was deep and cloudless, and the sun shone upon countless hosts of bright and happy faces. At the bars without Aldgate, on the Whitechapel road, Queen Mary was met by the Princess Elizabeth, accompanied by a large cavalcade of knights and dames. An affectionate greeting passed between the royal sisters, who had not met since the death of Edward, and the usurpation of Jane, by which both their claims to the throne had been set aside. But it was noted by those who closely observed them, that Mary’s manner grew more grave as Elizabeth rode by her side. The Queen was mounted upon a beautiful milk-white palfrey, caparisoned in crimson velvet, fringed with golden thread. She was habited in a robe of violet-coloured velvet, furred with powdered ermine, and wore upon her head a caul of cloth of tinsel set with pearls, and above this a massive circlet of gold covered with gems of inestimable value. Though a contrary opinion is generally entertained, Mary was not without some pretension to beauty. Her figure was short and slight, but well proportioned; her complexion rosy and delicate; and her eyes bright and piercing, though, perhaps, too stern in their expression. Her mouth was small, with thin compressed lips, which gave an austere and morose character to an otherwise-pleasing face. If she had not the commanding port of her father, Henry the Eighth, nor the proud beauty of her mother, Catherine of Arragon, she inherited sufficient majesty and grace from them to well fit her for her lofty station.

No one has suffered more from misrepresentation than this queen. Not only have her failings been exaggerated, and ill qualities, which she did not possess, attributed to her, but the virtues that undoubtedly belonged to her, have been denied her. A portrait, perhaps too flatteringly coloured, has been left of her by Michele, but still it is nearer the truth than the darker presentations with which we are more familiar. “As to the more important qualities of her mind, with a few trifling exceptions, (in which, to speak the truth, she is like other women, since besides being hasty and somewhat resentful, she is rather more parsimonious and miserly than is fitting a munificent and liberal sovereign,) she has in other respects no notable imperfection, and in some things she is without equal; for not only she is endowed with a spirit beyond other women who are naturally timid, but is so courageous and resolute that no adversity nor danger ever caused her to betray symptoms of pusillanimity. On the contrary, she has ever preserved a greatness of mind and dignity that is admirable, knowing as well what is due to the rank she holds as the wisest of her councillors, so that in her conduct and proceedings during the whole of her life, it cannot be denied she has always proved herself to be the offspring of a truly royal stock. Of her humility, piety, and observance of religious duties, it is unnecessary to speak, since they are well known, and have been proved by sufferings little short of martyrdom; so that we may truly say of her with the Cardinal, that amidst the darkness and obscurity which overshadowed this kingdom, she remained like a faint flame strongly agitated by winds which strove to extinguish it, but always kept alive by her innocence and true faith, in order that she might one day shine to the world, as she now does.” Other equally strong testimonies to her piety and virtue might be adduced. By Camden she is termed a “lady never sufficiently to be praised for her sanctity, charity, and liberality.” And by Bishop Godwin—“a woman truly pious, benign, and of most chaste manners, and to be lauded, if you do not regard her failure in religion.” It was this “failure in religion” which has darkened her in the eyes of her Protestant posterity. With so many good qualities it is to be lamented that they were overshadowed by bigotry.

If Mary did not possess the profound learning of Lady Jane Grey, she possessed more than ordinary mental acquirements. A perfect mistress of Latin, French, Spanish and Italian, she conversed in the latter language with fluency. She had extraordinary powers of eloquence when roused by any great emotion, and having a clear logical understanding, was well fitted for argument. Her courage was undaunted; and she possessed much of the firmness of character—obstinacy it might perhaps be termed, of her father. In the graceful accomplishment of the dance, she excelled, and was passionately fond of music, playing with skill on three instruments, the virginals, the regals, and the lute. She was fond of equestrian exercise, and would often indulge in the chace. She revived all the old sports and games which had been banished as savouring of mummery by the votaries of the reformed faith. One of her sins in their eyes was a fondness for rich apparel. In the previous reign female attire was remarkable for its simplicity. She introduced costly stuffs, sumptuous dresses, and French fashions.

In personal attractions the Princess Elizabeth far surpassed her sister. She was then in the bloom of youth, and though she could scarcely be termed positively beautiful, she had a very striking appearance, being tall, portly, with bright blue eyes, and exquisitely formed hands, which she took great pains to display.

As soon as Elizabeth had taken her place behind the Queen, the procession set forward. The first part of the cavalcade consisted of gentlemen clad in doublets of blue velvet, with sleeves of orange and red, mounted on chargers trapped with close housings of blue sarsenet powdered with white crosses. After them rode esquires and knights, according to their degree, two and two, well mounted, and richly apparelled in cloth of gold, silver, or embroidered velvet, “fresh and goodlie to behold.” Then came the trumpeters, with silken pennons fluttering from their clarions, who did their devoir gallantly. Then a litter covered with cloth of gold, drawn by richly-caparisoned horses, and filled by sumptuously-apparelled dames. Then an immense retinue of nobles, knights, and gentlemen, with their attendants, all dressed in velvets, satins, taffeties, and damask of all colours, and of every device and fashion—there being no lack of cloths of tissue, gold, silver, embroidery, or goldsmith’s work. Then came forty high-born damsels mounted on steeds, trapped with red velvet, arrayed in gowns and kirtles of the same material. Then followed two other litters covered with red satin. Then came the Queen’s body guard of archers, clothed in scarlet, bound with black velvet, bearing on their doublets a rose woven in gold, under which was an imperial crown. Then came the judges; then the doctors; then the bishops; then the council; and, lastly, the knights of the Bath in their robes.

Before the Queen rode six lords, bare-headed, four of whom carried golden maces. Foremost amongst these rode the Earls of Pembroke and Arundel, bearing the arms and crown. They were clothed in robes of tissue, embroidered with roses of fine gold, and each was girt with a baldrick of massive gold. Their steeds were trapped in burnt silver, drawn over with cords of green silk and gold, the edges of their apparel being fretted with gold and damask. The Queen’s attire has been already described. She was attended by six lacqueys habited in vests of gold, and by a female attendant in a grotesque attire, whom she retained as her jester, and who was known among her household by the designation of Jane the Fool. The Princess Elizabeth followed, after whom came a numerous guard of archers and arquebussiers. The retinue was closed by the train of the ambassadors, Noailles and Renard. A loud discharge of ordnance announced the Queen’s arrival at Aldgate. This was immediately answered by the Tower guns, and a tremendous and deafening shout rent the air. Mary appeared greatly affected by this exhibition of joy, and as she passed under the ancient gate which brought her into the city, and beheld the multitudes assembled to receive her, and heard their shouts of welcome, she was for a moment overcome by her feelings. But she speedily recovered herself, and acknowledged the stunning cries with a graceful inclination of her person.

Upon a stage on the left, immediately within the gate, stood a large assemblage of children, attired like wealthy merchants, one of whom—who represented the famous Whittington—pronounced an oration to the Queen, to which she vouchsafed a gracious reply. Before this stage was drawn up a little phalanx, called the “Nine children of honour.” These youths were clothed in velvet, powdered with flowers-de-luce, and were mounted on great coursers, each of which had embroidered on its housing a scutcheon of the Queen’s title—as of England, France, Gascony, Guienne, Normandy, Anjou, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland. As soon as the oration was ended, the Lord Mayor, Aldermen, Sheriffs, and their officers and attendants, rode forth to welcome the Queen to the city. The Lord Mayor was clothed in a gown of crimson velvet, decorated with the collar of SS., and carried the mace. He took his place before the Earl of Arundel, and after some little delay the cavalcade was again set in motion. First marched the different civic crafts, with bands of minstrelsy and banners; then the children who had descended from the stage; then the nine youths of honour; then the city guard; and then the Queen’s cavalcade as before described.

Mary was everywhere received with the loudest demonstrations of joy. Prayers, wishes, welcomings, and vociferations attended her progress. Nothing was heard but “God save your highness—God send you a long and happy reign.” To these cries, whenever she could make herself heard, the Queen rejoined, “God save you, all my people. I thank you with all my heart.” Gorgeous pageants were prepared at every corner. The conduits ran wine. The crosses and standards in the city wore newly painted and burnished. The bells pealed, and loud-voiced cannon roared. Triumphal arches covered with flowers, and adorned with banners, targets, and rich stuffs, crossed the streets. Largesse was showered among the crowd with a liberal hand, and it was evident that Mary’s advent was hailed on all hands as the harbinger of prosperity. The train proceeded along Fenchurch Street, where was a “marvellous cunning’ pageant, representing the fountain of Helicon, made by the merchants of the Stillyard; the fountain ran abundantly-racked Rhenish wine till night.” At the corner of Gracechurch Street there was another pageant, raised to a great height, on the summit of which were four pictures; above these stood an angel robed in green, with a trumpet to its mouth, which was sounded at the Queen’s approach, to the “great marvelling of many ignorant persons.” Here she was harangued by the Recorder; after which the Chamberlain presented her with a purse of cloth of gold, containing a thousand marks. The purse she graciously received, but the money she distributed among the assemblage. At the corner of Gracechurch Street another stage was erected. It was filled with the loveliest damsels that could be found, with their hair loosened and floating over their shoulders, and carrying large branches of white wax. This was by far the prettiest spectacle she had witnessed, and elicited Mary’s particular approbation. Her attention, however, was immediately afterwards attracted to the adjoining stage, which was filled with Romish priests in rich copes, with crosses and censers of silver, which they waved as the Queen approached, while an aged prelate advanced to pronounce a solemn benediction upon her. Mary immediately dismounted, and received it on her knees. This action was witnessed with some dislike by the multitude, and but few shouts were raised as she again mounted her palfrey. But it was soon forgotten, and the same cheers that had hitherto attended her accompanied her to the Tower. Traversing East-cheap, which presented fresh crowds, and offered fresh pageants to her view, she entered Tower Street, where she was welcomed by larger throngs than before, and with greater enthusiasm than ever. In this way she reached Tower Hill, where a magnificent spectacle burst upon her.

The vast area of Tower Hill was filled with spectators. The crowds who had witnessed her entrance into the city had now flocked thither, and every avenue had poured in its thousands, till there was not a square inch of ground unoccupied. Many were pushed into the moat, and it required the utmost exertion of the guards, who were drawn out in lines of two deep, to keep the road which had been railed and barred from the end of Tower Street to the gates of the fortress clear for the Queen. As Mary’s eye ranged over this sea of heads—as she listened to their stunning vociferations, and to the loud roar of the cannon which broke from every battlement in the Tower, her heart swelled with exultation. It was an animating spectacle. The day, it has been said, was bright and beautiful. The sun poured down its rays upon the ancient fortress, which had so lately opened its gates to an usurper, but which now like a heartless rake had cast off one mistress to take another. The whole line of ramparts on the west was filled with armed men. On the summit of the White Tower floated her standard, while bombard and culverin kept up a continual roar from every lesser tower.

After gazing for a few moments in the direction of the lofty citadel, now enveloped in the clouds of smoke issuing from the ordnance, and, excepting its four tall turrets and its standard, entirely hidden from view, her eyes followed the immense cavalcade, which, like a swollen current, was pouring its glittering tide beneath the arch of the Bulwark Gate; and as troop after troop disappeared, and she gradually approached the fortress, she thought she had never beheld a sight so grand and inspiriting. Flourishes of trumpets, almost lost in the stunning acclamations of the multitude, and the thunder of artillery, greeted her arrival at the Tower. Her entrance was conducted with much ceremony. Proceeding through closely-serried ranks of archers and arquebussiers, she passed beneath the Middle Gate and across the bridge. At the By-ward Tower she was received by Lord Clinton and a train of nobles. On either side of the gate, stood Gog and Magog. Both giants made a profound obesiance as she passed. A few steps further, her course was checked by. Og and Xit. Prostrating himself before her, the elder giant assisted his diminutive companion to clamber upon his back, and as soon as he had gained this position, the dwarf knelt down, and offered the keys of the fortress to the Queen. Mary was much diverted at the incident, nor was she less surprised at the vast size of Og and his brethren—than at the resemblance they presented to her royal father. Guessing what was passing through her mind, and regardless of consequences as of decorum, Xit remarked,—

“Your majesty, I perceive, is struck with the likeness of my worthy friend Og to your late sire King Henry VIII., of high and renowned memory. You will not, therefore, be surprised, when I inform you that he is his—”

Before another word could be uttered, Og, who had been greatly alarmed at the preamble, arose with such suddenness, that Xit was precipitated to the ground.

“Pardon me, your majesty,” cried the giant, in great confusion, “it is true what the accursed imp says. I have the honour to be indirectly related to your highness. God’s death, sirrah, I have half a mind to set my foot upon thee and crush thee. Thou art ever in mischief.”

The look and gesture, which accompanied this exclamation, were so indescribably like their royal parent, that neither the Queen nor the Princess Elizabeth could forbear laughing.

As to Xit, the occurrence gained him a new friend in the person of Jane the Fool, who ran up as he was limping off with a crestfallen look, and begged her majesty’s permission to take charge of him. This was granted, and the dwarf proceeded with the royal cortege. On learning the name of his protectress, Xit observed,—

“You are wrongfully designated, sweetheart. Jane the Queen was Jane the Fool—you are Jane the Wise.”

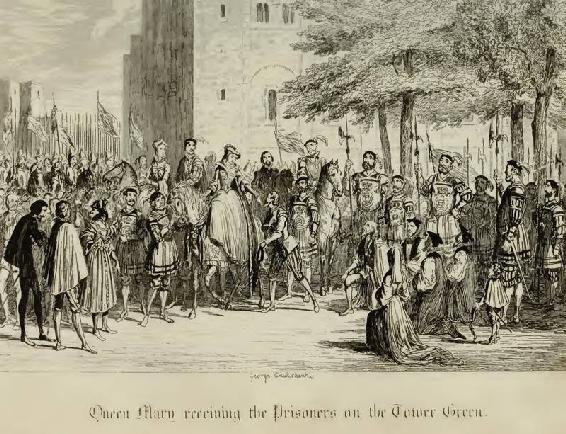

While this was passing, Mary had given some instructions in an under tone to Lord Clinton, and he immediately departed to fulfil them. The cavalcade next passed beneath the arch of the Bloody Tower, and the whole retinue drew up on the Green. A wide circle was formed round the queen, amid which, at intervals, might be seen the towering figures of the giants, and next to the elder of them, Xit, who having been obliged to quit his new friend had returned to Og and was standing on his tip-toes to obtain a peep at what was passing. No sooner had Mary taken up her position, than Lord Clinton re-appeared, and brought with him several illustrious persons who having suffered imprisonment in the fortress, for their zeal for the religion of Rome, wore now liberated by her command. As the first of the group, a venerable nobleman, Approached her and bent the knee before her, Mary’s eyes filled with tears, and she exclaimed, in a voice of much emotion,—

“Arise, my Lord Duke of Norfolk. The attainder pronounced against you in my father’s reign is reversed. Your rank, your dignities, honours, and estates shall be restored to you.”

As the Duke retired, Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, advanced.

“Your Grace shall not only have your bishoprick again,” said Mary, “but you shall have another high and important office.—I here appoint you Lord Chancellor of the realm.”

“Your highness overwhelms me with kindness,” replied Gardiner, pressing her hand to his lips.

“You have no more than your desert, my lord,” replied Mary. “But I pray you stand aside a moment. There are other claimants of our attention.”

Gardiner withdrew, and another deprived bishop took his place. It was Bonner.

“My lord,” said Mary, as he bowed before her, “you are restored to the see of London, and the prelate who now so unworthily fills that high post, Bishop Ridley, shall make room for you. My lord,” she added to Lord Clinton, “make out a warrant, and let him be committed to the Tower.”

“I told you how it would be,” observed Renard to Lord Pembroke. “Ridley’s last discourse has cost him his liberty. Cranmer will speedily follow.”

Other prisoners, amongst whom was Tunstall, Bishop of Durham, and the Duchess of Somerset, now advanced, and were warmly welcomed by the Queen. The last person who approached her was a remarkably handsome young man, with fine features and a noble figure. This was Edward Courtenay, son of the Marquess of Exeter, who was beheaded in 1538. Since that time Courtenay had been a close prisoner in the Tower. He was of the blood-royal, being grandson of Catherine, youngest daughter of Edward the Fourth, and his father had been declared heir to the throne.

“You are right welcome, my cousin,” said Mary, extending her hand graciously to him, which he pressed to his lips. “Your attainder shall be set aside, and though we cannot restore your father to life, we can repair the fortunes of his son, and restore him to his former honours. Henceforth, you are Earl of Devonshire. Your patent shall be presently made out, and such of your sire’s possessions as are in our hands restored.”

Courtenay warmly thanked her for her bounty, and the Queen smiled upon him in such gracious sort, that a suspicion crossed more than one bosom that she might select him as her consort.

“Her majesty smiles upon Courtenay as if she would bestow her hand upon him in right earnest,” observed Pembroke to Renard.

“Hum!” replied the ambassador. “This must be nipped in the bud. I have another husband in view for her.”

“Your master, Philip of Spain, I’ll be sworn,” said Pembroke—“a suitable match, if he were not a Catholic.”

Renard made no answer, but he smiled an affirmative.

“I am glad this scheme has reached my ears,” observed De Noailles, who overheard the conversation—“it will not suit my master, Henry II., that England should form an alliance with Spain. I am for Courtenay, and will thwart Renard’s plot.”

Having received the whole of the prisoners, Mary gave orders to liberate all those within the Tower who might be confined for their adherence to the Catholic faith.

“My first care,” she said, “shall be to celebrate the obsequies of my brother, Edward VI.,—whose body, while others have been struggling for the throne, remains uninterred according to the forms of the Romish church. The service shall take place in Westminster Abbey.”

“That may not be, your highness,” said Cranmer, who formed one of the group. “His late majesty was a Protestant prince.”

“Beware how you oppose me, my lord,” rejoined Mary, sternly. “I have already committed Ridley to prison, and shall not hesitate to commit your Grace.”

“Your highness will act as it seems best to you,” rejoined Cranmer, boldly; “but I shall fulfil my duty, even at the hazard of incurring your displeasure. Your royal brother professed the Protestant faith, which is, as yet,—though Heaven only knows how long it may continue so,—the established religion of this country, and he must, therefore, be interred according to the rites of that church. No other ceremonies, but those of the Protestant church, shall be performed within Westminster Abbey, as long as I maintain a shadow of power.”

“It is well,” replied Mary. “We may find means to make your Grace more flexible. To-morrow, we shall publish a decree proclaiming our religious opinions. And it is our sovereign pleasure, that the words ‘Papist’ and ‘Heretic’ be no longer used as terms of reproach.”

“I have lived long enough,” exclaimed the Duke of Norfolk, falling on his knees—“in living to see the religion of my fathers restored.”

“The providence which watched over your Grace’s life, and saved you from the block, when your fate seemed all but sealed, reserved you for this day,” rejoined Mary.

“It reserved me to be a faithful and devoted servant of your majesty,” replied the Duke.

“What is your highness’s pleasure touching the Duke of Northumberland, Lord Guilford Dudley, and Lady Jane Dudley?” inquired Clinton.

“The two latter will remain closely confined till their arraignment,” replied Mary. “Lady Jane, also, will remain a prisoner for the present. And now, my lords, to the palace.”

With this, she turned her palfreys head, and passing under the Bloody Tower, proceeded to the principal entrance of the ancient structure, where she dismounted, and accompanied by a throng of nobles, dames, and attendants, entered the apartments so lately occupied by the unfortunate Jane.