In 1078, (for, instead of following the warder’s narrative to Simon Renard, it appears advisable in this place to offer a slight sketch of the renowned fortress, under consideration, especially as such a course will allow of its history being brought down to a later period than could otherwise be accomplished,) the Tower of London was founded by William the Conqueror, who appointed Gundulph, Bishop of Exeter, principal overseer of the work. By this prelate, who seems to have been a good specimen of the church militant, and who, during the progress of his operations, was lodged in the house, of Edmere, a burgess of London, a part of the city wall, adjoining the northern banks of the Thames, which had been much injured by the incursions of the tide, was taken down, and a “great square tower,” since called the White Tower, erected on its site.

Some writers have assigned an earlier date to this edifice, ascribing its origin to the great Roman invader of our shores, whence it has been sometimes denominated Cæsar’s Tower; and the hypothesis is supposed to be confirmed by Fitz Stephens, a monkish historian of the period of Henry the Second, who states, that “the city of London hath in the east a very great and most strong Palatine Tower, whose turrets and walls do rise from a deep foundation, the mortar thereof being tempered with the blood of beasts.” On this authority, Dr. Stukeley has introduced a fort, which he terms the Arx Palatina, in his plan of Londinium Augusta. But, though it is not improbable that some Roman military station may have stood on the spot now occupied by the White Tower,—certain coins and other antiquities having been found by the workmen in sinking the foundations of the Ordnance Office in 1777,—it is certain that no part of the present structure was erected by Julius Cæsar; nor can he, with propriety, be termed the founder of the Tower of London. As to its designation, that amounts to little, since, as has been shrewdly remarked by M. Dulaure, in his description of the Grand Châtelet at Paris—“every old building, the origin of which is buried in obscurity, is attributed to Cæsar or the devil.”

Fourteen years afterwards, in the reign of William Rufus, who, according to Henry of Huntingdon, “pilled and shaved the people with tribute, especially about the Tower of London,” the White Tower was greatly damaged by a violent storm, which, among other ravages, carried off the roof of Bow Church, and levelled above six hundred habitations with the ground. It was subsequently repaired, and an additional tower built on the south side near the river.

Strengthened by Geoffrey de Magnaville, Earl of Essex, and fourth constable of the fortress, who defended it against the usurper Stephen, but was, nevertheless, eventually compelled to surrender it; repaired in 1155, by Thomas à Becket, then Chancellor to Henry the Second; greatly extended and enlarged in 1190, the second year of the reign of Richard Cour de Lion, by William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely and Chancellor of the realm, who, encroaching to some distance upon Tower Hill, and breaking down the city wall as far as the first gate called the postern, surrounded it with high embattled walls of stone, and a broad deep ditch, thinking, as Stowe observes, “to have environed it with the river Thames;”—the Tower of London was finished by Henry the Third, who, in spite of the remonstrances of the citizens, and other supernatural warnings, if credit is to be attached to the statement of Matthew of Paris, completely fortified it.

A gate and bulwark having been erected on the west of the Tower, we are told by the old chronicler above-mentioned, “that they were shaken as it had been with an earthquake and fell down, which the king again commanded to be built in better sort, which was done. And yet, again, in the year 1241, the said wall and bulwarks that were newly builded, whereon the king had bestowed more than twelve thousand marks, were irrecoverably quite thrown down as before; for the which chance the citizens of London were nothing sorry, for they were threatened, that the said wall and bulwarks were builded, to the end, that if any of them would contend for the liberties of the city, they might be imprisoned. And that many might be laid in divers prisons, many lodgings were made, that no one should speak with another.” These remarkable accidents (if accidents they were,) were attributed by the popular superstition of the times, to the miraculous interference of Thomas à Becket, the guardian saint of the Londoners.

By the same monarch the storehouse was strengthened and repaired, and the keep or citadel whitened, (whence probably it derived its name, as it was afterwards styled in Edward the Third’s reign “La Blanche Tour”) as appears by the following order still preserved in the Tower Rolls:—“We command you to repair the garner within the said tower, and well amend it throughout, wherever needed. And also concerning all the leaden gutters of the Great Tower, from the top of the said tower, through which the rain water must fall down, to lengthen them, and make them come down even to the ground; so that the wall of the said tower, lately whitened anew, may by no means decay, nor easily break out, by reason of the rain water dropping down. But to make upon the said towers alures of good and strong timber, and throughout to be well leaded; by which people might see even to the foot of the said tower, and better to go up and down, if need be.” Further orders were given in this reign for the beautifying and fitting up the chapels of Saint John and Saint Peter, as already mentioned in the account of those structures.

The same monarch planted a grove, or orchard of “perie trees,” as they are described in his mandate to Edward of Westminster, in the vicinity of the Tower, and surrounded it with a wall of mud, afterwards replaced by another of brick, in the reign of Edward the Fourth. He likewise established a menagerie within the fortress, allotting a part of the bulwark at the western entrance since called the Lions’ Tower, for the reception of certain wild beasts, and as a lodging for their keeper. In 1235, the Emperor Frederick sent him three leopards, in allusion to his scutcheon, on which three of those animals were emblazoned; and from that time, down to a very recent date, a menagerie has been constantly maintained within the Tower. To support it, Edward the Second commanded the Sheriffs of London to pay the keeper of his lions sixpence a day for their food, and three half-pence a-day for the man’s own diet, out of the fee farm of the city.

Constant alterations and reparations wero made to the ramparts and towers during subsequent reigns. Edward the Fourth encroached still further on Tower Hill than his predecessors, and erected an outer gate called the Bulwark Tower. In the fifth year of the reign of this monarch, a scaffold and gallows having been erected on Tower Hill, the citizens, ever jealous of their privileges and liberties, complained of the step; and to appease them, a proclamation was made to the effect, “that the erection, and setting up of the said gallows be not a precedent or example thereby hereafter to be taken, in hurt, prejudice, or derogation, of the franchises, liberties, and privileges of the city.”

Richard the Third repaired the Tower, and Stow records a commission to Thomas Daniel, directing him to seize for use within this realm, as many masons, bricklayers, and other workmen, as should be thought necessary for the expedition of the king’s works within the Tower. In the twenty-third of Henry the Eighth, the whole of the fortress appears to have undergone repair—a survey being taken of its different buildings, which is is still preserved in the Chapter-house at Westminster. In the second of Edward the Sixth, the following strange accident occurred, by which one of the fortifications was destroyed. A Frenchman, lodged in the Middle Tower, accidentally set fire to a barrel of gunpowder, which blew up the structure, fortunately without damage to any other than the luckless causer of it.

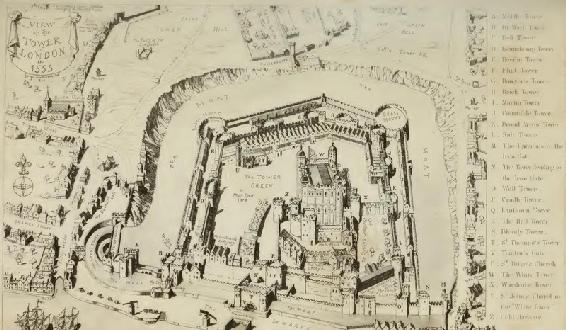

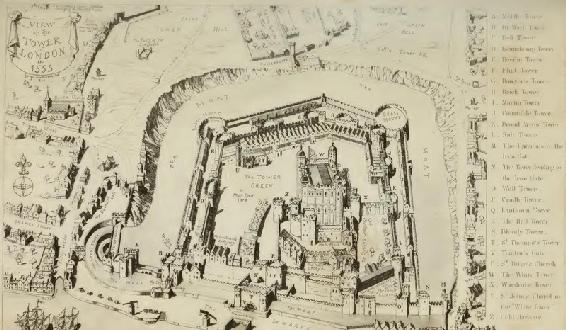

At the period of this chronicle, as at the present time, the Tower of London comprehended within its walls a superficies of rather more than twelve acres, and without the moat a circumference of three thousand feet and upwards. Consisting of a citadel or keep, surrounded by an inner and outer ward, it was approached on the west by an entrance called the Bulwark Gate, which has long since disappeared. The second entrance was formed by an embattled tower, called the Lion’s Gate, conducting to a strong tower flanked with bastions, and defended by a double portcullis, denominated the Middle Tower. The outworks adjoining these towers, in which was kept the menagerie, were surrounded by a smaller moat, communicating with the main ditch. A large drawbridge then led to another portal, in all respects resembling that last described, forming the principal entrance to the outer ward, and called the By-ward or Gate Tower. The outer ward was defended by a strong line of fortifications; and at the north-east corner stood a large circular bastion, called the Mount.

The inner ward or ballium was defended by thirteen towers, connected by an embattled stone wall about forty feet, high and twelve feet thick, on the summit of which was a footway for the guard. Of these towers, three were situated at the west, namely, the Bell, the Beauchamp and the Devilin Towers; four at the north, the Flint, the Bowyer, the Brick, and the Martin Towers; three at the east, the Constable, the Broad Arrow, and Salt Towers; and three on the south, the Well, the Lanthorn, and the Bloody Tower. The Flint Tower has almost disappeared; the Bowyer Tower only retains its basement story; and the Brick Tower has been so much modernized as to retain little of its pristine character. The Martin Tower is now denominated the Jewel Tower, from the circumstance of its being the depositary of the regalia. The Lanthorn Tower has been swept away with the old palace.

Returning to the outer ward, the principal fortification on the south was a large square structure, flanked at each angle by an embattled tower. This building, denominated Saint Thomas’s, or Traitor’s Tower, was erected across the moat, and masked a secret entrance from the Thames, through which state prisoners, as has before been related, were brought into the Tower. It still retains much of its original appearance, and recals forcibly to the mind of the observer the dismal scenes that have occurred beneath its low-browed arches. Further on the east, in a line with Traitor’s Tower, and terminating a wing of the old palace, stood the Cradle Tower. At the eastern angle of the outer ward was a small fortification over-looking the moat, known as the Tower leading to the Iron Gate. Beyond it a draw-bridge crossed the moat, and led to the Iron Gate, a small portal protected by a tower, deriving its name from the purpose for which it was erected.

At this point, on the patch of ground intervening between the moat and the river, and forming the platform or wharf, stood a range of mean habitations, occupied by the different artisans and workmen employed in the fortress. At the south of the By-ward Tower, an arched and embattled gateway opened upon a drawbridge which crossed the moat at this point. Opposite this drawbridge were the main stairs leading to the edge of the river. The whole of the fortress, it is scarcely necessary to repeat, was (and still is) encompassed by a broad deep moat, of much greater width at the sides next to Tower Hill and East Smithfield, than at the south, and supplied with water from the Thames by the sluice beneath Traitor’s Gate.

Having now made a general circuit of the fortress, we shall return to the inner ballium, which is approached on the south by a noble gateway, erected in the reign of Edward the Third. A fine specimen of the architecture of the fourteenth century, this portal is vaulted with groined arches adorned with exquisite tracery springing from grotesque heads. At the period of this chronicle, it was defended at each end by a massive gate clamped with iron, and a strong portcullis. The gate and portcullis at the southern extremity still exist, but those at the north have been removed. The structure above it was anciently called the Garden Tower; but subsequently acquired the appellation of the Bloody Tower, from having been the supposed scene of the murder of the youthful princes, sons of Edward the Fourth, by the ruthless Duke of Gloucester, afterwards Richard the Third. Without pausing to debate the truth of this tragical occurrence, it may be sufficient to mention that tradition assigns it to this building.

Proceeding along the ascent leading towards the green, and mounting a flight of stone steps on the left, we arrive in front of the ancient lodgings allotted to the lieutenant of the Tower. Chiefly constructed of timber, and erected at the beginning of the sixteenth century, this fabric has been so much altered, that it retains little of its original character. In one of the rooms, called, from the circumstance, the Council-chamber, the conspirators concerned in the Gunpowder Plot were interrogated; and in memory of the event, a piece of sculpture, inscribed with their names, and with those of the commissioners by whom they were examined, has been placed against the walls.

Immediately behind the lieutenant’s lodgings stands the Bell Tower,—a circular structure, surmounted by a small wooden turret containing the alarm-bell of the fortress. Its walls are of great thickness, and light is admitted through narrow loopholes. On the basement floor is a small chamber, with deeply-recessed windows, and a vaulted roof of very curious construction. This tower served as a place of imprisonment to John Fisher, the martyred bishop of Rochester, beheaded on Tower Hill for denying Henry the Eighth’s supremacy; and to the Princess Elizabeth, who was confined within it by her sister, Queen Mary.

Traversing the green, some hundred and forty feet brings us to the Beauchamp, or Cobham Tower, connected with the Bell Tower by means of a footway on the top of the ballium wall. Erected in the reign of Henry the Third, as were most of the smaller towers of the fortress, this structure appears, from the numerous inscriptions, coats of arms, and devices that crowd its walls, to have been the principal state-prison. Every room, from roof to vault, is covered with melancholy memorials of its illustrious and unfortunate occupants.

Over the fire-place in the principal chamber, (now used as a mess-room by the officers of the garrison,) is the autograph of Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel, beheaded in 1572, for aspiring to the hand of Mary Queen of Scots. On the right of the fire-place, at the entrance of a recess, are these words:—“Dolor Patientia vincitur. G. Gyfford. August 8, 1586.” Amongst others, for we can only give a few as a specimen of the rest, is the following enigmatical inscription. It is preceded by the date 1568, April 28, but is unaccompanied by any signature.

NO HOPE IS BARD OR BAYNE

THAT HAPP DOTH OUS ATTAYNE.

The next we shall select is dated 1581, and signed Thomas Myagh.

THOMAS MIAGII WHICH LIETHE HERE ALONE

THAT FAYNE WOLD FROM HENCE BEGON

BY TORTURE STRAUNGE MI TROVTH WAS TRYED

YET OF MY LIBERTIE DENIED.

Of this unfortunate person the following interesting account is given by Mr. Jardine, in his valuable treatise on the Use of Torture in the Criminal Law of England. “Thomas Myagh was an Irishman who was brought over by the command of the Lord Deputy of Ireland, to be examined respecting a treasonable correspondence with the rebels in arms in that country. The first warrant for the torture of this man was probably under the sign-manual, as there is no entry of it in the council register. The two reports made by the Lieutenant of the Tower and Dr. Hammond, respecting their execution of this warrant, are, however, to be seen at the State-Paper Office. The first of these, which is dated the 10th of March, 1580-1, states that they had twice examined Myagh, but had forborne to put him in Skevington’s Irons, because they had been charged to examine him with secrecy, ‘which they could not do, that manner of dealing requiring the presence and aid of one of the jailors all the time that he should be in those irons,’ and also because they ‘found the man so resolute, as in their opinions little would be wrung out of him but by some sharper torture.’ The second report, which is dated the 17th of March, 1580, merely states that they had again examined Myagh, and could get nothing from him, ‘notwithstanding that they had made trial of him by the torture of Skevington’s irons, and with so much sharpness, as was in their judgment for the man and his cause convenient.’ How often Myagh was tortured does not appear; but Skevington’s irons seem to have been too mild a torture, for on the 30th of July, 1581, there is an entry in the council books of an authority to the Lieutenant of the Tower and Thomas Norton, to deal with him with the rack in such sort as they should see cause.”

From many sentences expressive of the resignation of the sufferers, we take the following, subscribed A. Poole, 1564:—“Deo. servire. penitentiam. inire. fato. ohedire. regnare. est.” Several inscriptions are left by this person—one four years later than the foregoing, is as follows: “A passage perillus maketh a port pleasant.” Here is another sad memento: “O miser Hyon, che pensi od essero.” Another: “Reprens le: sage: et: il: te: aimera: J. S. 1538.” A third: “Principium sapientio timor Domini, I. h. s. x. p. s. Be friend to one. Be ennemye to none. Anno D. 1571, 10 Sept. The most unhappy man in the world is he that is not patient in adversities: For men are not killed with the adversities they have, but with the impatience they suffer. Tout vient apoint, quy peult attendre. Gli sospiri ne son testimoni veri dell angoscia mia. Æt. 20. Charles Bailly.”.

Most of these records breathe resignation. But the individual who carved the following record, and whose naine has passed away, appears to have numbered every moment of his captivity: “Close prisoner 8 months, 32 wekees, 224 dayes, 5376 houres.” How much of anguish is comprised in this brief sentence!

We could swell out this list, if necessary, to a volume, but the above may suffice to show their general character. Let those who would know how much their forefathers have endured cast their eyes over the inscriptions in the Beauchamp Tower. In general they are beautifully carved, ample time being allowed the writers for their melancholy employment. It has been asserted that Anne Boleyn was confined in the uppermost room of the Beauchamp Tower. But if an inscription may be trusted, she was imprisoned in the Martin Tower (now the Jewel Tower) at that time a prison lodging.

Postponing the description of the remaining towers until we have occasion to speak of them in detail, we shall merely note, in passing, the two strong towers situated at the southwestern extremity of the White Tower, called the Coal Harbour Gate, over which there was a prison denominated the Nun’s Bower, and proceed to the palace, of which, unluckily for the lovers of antiquity, not a vestige now remains.

Erected at different periods, and consisting of a vast range of halls, galleries, courts and gardens, the old palace occupied, in part, the site of the modern Ordnance Office. Commencing at the Coal Harbour Gate, it extended in a south-easterly direction to the Lanthorn Tower, and from thence branched off in a magnificent pile of building, called the Queen’s Gallery, to the Salt Tower. In front of this gallery, defended by the Cradle Tower and the Well Tower, was the privy garden. Behind it stretched a large quadrangular area, terminated at the western angle by the Wardrobe Tower, and at the eastern angle by the Broad Arrow Tower. It was enclosed on the left by a further range of buildings, termed the Queen’s Lodgings, and on the right by the inner ballium wall. The last-mentioned buildings were also connected with the White Tower, and with a small embattled structure flanked by a circular tower, denominated the Jewel House where the regalia were then kept. In front of the Jewel House stood a large decayed hall, forming part of the palace; opposite which was a court, planted with trees, and protected by the ballium wall.

This ancient palace—the scene of so many remarkable historical events,—the residence, during certain portions of their reigns, of all our sovereigns, from William Rufus down to Charles the Second—is now utterly gone. Where is the glorious hall which Henry the Third painted with the story of Antiochus, and which it required thirty fir-trees to repair,—in which Edward the Third and all his court were feasted by the captive John,—in which Richard the Second resigned his crown to Henry of Lancaster,—in which Henry the Eighth received all his wives before their espousals,—in which so many royal councils and royal revels have been held;—where is that great hall? Where, also, is the chamber in which Queen Isabella, consort of Edward the Second, gave birth to the child called, from the circumstance, Joan of the Tower? They have vanished, and other structures occupy their place. Demolished in the reign of James the Second, an ordnance office was erected on its site; and this building being destroyed by fire in 1788, it was succeeded by the present edifice bearing the name.

Having now surveyed the south of the fortress, we shall return to the north. Immediately behind Saint Peter’s Chapel stood the habitations of the officers of the then ordnance department, and next to them an extensive range of storehouses, armouries, granaries, and other magazines, reaching to the Martin Tower. On the site of these buildings was erected, in the reign of William the Third, that frightful structure, which we trust the better taste of this, or some future age will remove—the Grand Storehouse. Nothing can be imagined more monstrous or incongruous than this ugly Dutch toy, (for it is little better,) placed side by side with a stern old Norman donjon, fraught with a thousand historical associations and recollections. It is the great blot upon the Tower. And much as the destruction of the old palace is to be lamented, the erection of such a building as this, in such a place, is infinitely more to be deplored. We trust to see it rased to the ground.

In front of the Constable Tower stood another range of buildings appropriated to the different officers and workmen connected with the Mint, which, until the removal of the place of coinage to its present situation on Little Tower Hill, it is almost needless to say, was held within the walls of the fortress.

The White Tower once more claims our attention. Already described as having walls of enormous thickness, this venerable stronghold is divided into four stories including the vaults. The latter consist of two large chambers and a smaller one, with a coved termination at the east, and a deeply-recessed arch at the opposite extremity. Light is admitted to this gloomy chamber by four semicircular-headed loopholes. At the north is a cell ten feet long by eight wide formed in the thickness of the wall, and receiving no light except from the doorway. Here tradition affirms that Sir Walter Raleigh was confined, and composed his History of the World.

Amongst other half-obliterated inscriptions carved on the arched doorway of this dungeon, are these: He that indvreth TO THE ENDE SHALL BE SAVID. M. 10. R. REDSTON. DAR. KENT. Ano. 1553.—Be feithful to the death and I will give the a crown of life. T. Fane. 1554. Above stands Saint John’s Chapel, and the upper story is occupied by the council-chamber and the rooms adjoining. A narrow vaulted gallery, formed in the thickness of the wall, communicating with the turret stairs, and pierced with semicircular-headed openings for the admission of light to the interior, surrounds this story. The roof is covered with lead, and crowned with four lofty turrets, three angular and one square, surmounted with leaden cupolas, each terminated with a vane and crown.

We have spoken elsewhere, and shall have to speak again of the secret and subterranean passages, as well as of the dungeons of the Tower; those horrible and noisome receptacles, deprived of light and air, infested by legions of rats, and flooded with water, into which the wretched captives were thrust to perish by famine, or by more expeditious means; and those dreadful contrivances, the Little Ease—and the Pit;—the latter a dark and gloomy excavation sunk to the depth of twenty feet.

To the foregoing hasty sketch, in which we have endeavoured to make the reader acquainted with the general outline of the fortress, we would willingly, did space permit, append a history of the principal occurrences that have happened within its walls. We would tell how in 1234, Griffith, Prince of Wales, in attempting to escape from the White Tower, by a line made of hangings, sheets, and table-cloths, tied together, being a stout heavy man, broke the rope, and falling from a great height, perished miserably—his head and neck being driven into his breast between the shoulders. How Edward the Third first established a Mint within the Tower, coining florences of gold. How in the reign of the same monarch, three sovereigns were prisoners there;—namely, John, King of France, his son Philip, and David, King of Scotland. How in the fourth year of the reign of Richard the Second, during the rebellion of Wat Tyler, the insurgents having possessed themselves of the fortress, though it was guarded by six hundred valiant persons, expert in arms, and the like number of archers, conducted themselves with extraordinary licence, bursting into the king’s chamber, and that of his mother, to both of whom they offered divers outrages and indignities; and finally dragged forth Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, and hurrying him to Tower Hill, hewed off his head at eight strokes, and fixed it on a pole on London Bridge, where it was shortly afterwards replaced by that of Wat Tyler.

How, in 1458, jousts were held on the Tower-Green by the Duke of Somerset and five others, before Queen Margaret of Anjou. How in 1471, Henry the Sixth, at that time a prisoner, was said to be murdered within the Tower; how seven years later, George Duke of Clarence, was drowned in a butt of Malmsey in the Bowyer Tower; and how five years after that, the youthful Edward the Fifth, and the infant Duke of York, were also said, for the tradition is more than doubtful, to be smothered in the Blood Tower. How in 1483, by command of the Duke of Gloucester, who had sworn he would not dine till he had seen his head off, Lord Hastings was brought forth to the green before the chapel, and after a short shrift, “for a longer could not be suffered, the protector made so much haste to dinner, which he might not go to until this were done, for saving of his oath,” his head was laid down upon a large log of timber, and stricken off.

How in 1512, the woodwork and decorations of Saint John’s chapel in the White Tower were burnt. How in the reign of Henry the Eighth, the prisons were constantly filled, and the scaffold deluged with blood. How Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, the hither of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, were beheaded. How the like fate attended the Duke of Buckingham, destroyed by Wolsey, the martyred John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, the wise and witty Sir Thomas More, Anne Boleyn, her brother Lord Rochford, Norris, Smeaton, and others; the Marquis of Exeter, Lord Montacute, and Sir Edward Neville; Thomas, Lord Cromwell, the counsellor of the dissolution of the monasteries; the venerable and courageous Countess of Salisbury; Lord Leonard Grey; Katherine Howard and Lady Rochford; and Henry, Earl of Surrey.

How, in the reign of Edward the Sixth, his two uncles, Thomas Seymour, Baron Sudley, and Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, were brought to the block; the latter, as has been before related, by the machinations of Northumberland.

Passing over, for obvious reasons, the reign of Mary, and proceeding to that of Elizabeth, we might relate how Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, was beheaded; how the dungeons were crowded with recusants and seminary priests; amongst others, by the famous Jesuits, fathers Campion and Persons; how Lord Stourton, whose case seems to have resembled the more recent one of Lord Ferrers, was executed for the murder of the Hartgills; how Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, shot himself in his chamber, declaring that the jade Elizabeth should not have his estate; and how the long catalogue was closed by the death of the Earl of Essex.

How, in the reign of James the First, Sir Walter Raleigh was beheaded, and Sir Thomas Overbury poisoned. How in that of Charles the First, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, and Archbishop Laud, underwent a similar fate. How in 1656, Miles Sunderland, having been condemned for high treason, poisoned himself; notwithstanding which, his body, stripped of all apparel, was dragged at the horse’s tail to Tower Hill, where a hole had been digged under the scaffold, into which it was thrust, and a stake driven through it. How, in 1661, Lord Monson and Sir Henry Mildmay suffered, and in the year following Sir Henry Vane. How in the same reign Blood attempted to steal the crown; and how Algernon Percy and Lord William Russell were executed.

How, under James the Second, the rash and unfortunate Duke of Monmouth perished. How, after the rebellion of 1715, Lords Derwentwater and Kenmuro were decapitated; and after that of 1745, Lords Kilmarnock, Bahnerino, and Lovat. How in 1760, Lord Ferrers was committed to the Tower for the murder of his steward, and expiated his offence at Tyburn. How Wilkes was imprisoned there for a libel in 1762; and Lord George Gordon for instigating the riots of 1780. How, to come to our own times, Sir Francis Burdett was conveyed thither in April 1810; and how, to close the list, the Cato-street conspirators, Thistlewood, Ings, and others, were confined there in 1820.

The chief officer appointed to the custody of the royal fortress, is termed the Constable of the Tower;—a place, in the words of Stowe, of “high honour and reputation, as well as of great trust, many earls and one duke having been constable of the Tower.” Without enumerating all those who have filled this important post, it maybe sufficient to state, that the first constable was Geoffrey de Mandeville, appointed by William the Conqueror; the last, Arthur, Duke of Wellington. Next in command is the lieutenant, after whom come the deputy-lieutenant, and major, or resident governor. The civil establishment consists of a chaplain, gentleman-porter, physician, surgeon, and apothecary; gentleman-jailer, yeoman porter, and forty yeomen warders. In addition to these, though in no way connected with the government or custody of the Tower, there are the various officers belonging to the ordnance department; the keepers of the records, the keeper of the regalia; and formerly there were the different officers of the Mint.

The lions of the Tower—once its chief attraction with the many,—have disappeared. Since the establishment of the Zoological Gardens, curiosity having been drawn in that direction, the dens of the old menagerie are deserted, and the sullen echoes of the fortress are no longer awakened by savage yells and howling. With another and more important attraction—the armories—it is not our province to meddle.

To return to Simon Renard and the warder. Having concluded his recital, to which the other listened with profound attention, seldom interrupting him with a remark, Winwike proposed, if his companion’s curiosity was satisfied, to descend.

“You have given me food for much reflection.” observed Renard, aroused from a reverie into which he had fallen; “but before we return I would gladly walk round the buildings. I had no distinct idea of the Tower till I came hither.”

The warder complied, and led the way round the battlements, pausing occasionally to point out some object of interest.

Viewed from the summit of the White Tower, especially on the west, the fortress still offers a striking picture. In the middle of the sixteenth century, when its outer ramparts were strongly fortified—when the gleam of corslet and pike was reflected upon the dark waters of its moat—when the inner ballium walls were entire and unbroken, and its thirteen towers reared their embattled fronts—when within each of those towers state prisoners were immured—when its drawbridges were constantly raised, and its gates closed—when its palace still lodged a sovereign—when councils were held within its chambers—when its secret dungeons were crowded—when Tower Hill boasted a scaffold, and its soil was dyed with the richest and best blood of the land—when it numbered among its inferior officers, jailors, torturers, and an executioner—when all its terrible machinery was in readiness, and could be called into play at a moment’s notice—when the steps of Traitor’s Gate wore worn by the feet of those who ascended, them—when, on whichever side the gazer looked, the same stern prospect was presented—the palace, the fortress, the prison,—a triple conjunction of fearful significance—when each structure had dark secrets to conceal—when beneath all these ramparts, towers, and bulwarks, were subterranean passages and dungeons—then, indeed, it presented a striking picture both to the eye and mind.

Slowly following his companion, Renard counted all the towers, which, including that whereon he was standing, and these connected with the bulwarks and palace, amounted to twenty-two,—marked their position—commented upon the palace, and the arrangement of its offices and outbuildings—examined its courts and gardens—inquired into the situation of the queen’s apartments, and was shown a long line of buildings with a pointed roof, extending from the south-east angle of the keep to the Lanthorn Tower—admired the magnificent prospect of the heights of Surrey and Kent—traced the broad stream of the Thames as far as Greenwich—suffered his gaze to wander over the marshy tract of country towards Essex—noted the postern gate in the ancient city walls, standing at the edge of the north bank of the moat—traced those walls by their lofty entrances from Aldgate to Cripplegate, and from thence returned to the church of All Hallows Barking, and Tower Hill. The last object upon which his gaze rested was the scaffold. A sinister smile played upon his features as he gazed on it.

“There,” he observed, “is the bloody sceptre by which England is ruled. From the palace to the prison is a step—from the prison to the scaffold another.”

“King Henry the Eighth gave it plenty of employment,” observed Winwike.

“True,” replied Renard; “and his daughter, Queen Mary, will not suffer it to remain idle.”

“Many a head will, doubtless, fall (and justly), in consequence of the late usurpation,” remarked the warder.

“The first to do so now rests within that building,” rejoined Renard, glancing at the Beauchamp Tower.

“Your worship, of course, means the Duke of Northumberland, since his grace is confined there,” returned the warder. “Well, if she is spared who, though placed foremost in the wrongful and ill-advised struggle, was the last to counsel it, I care not what becomes of the rest. Poor lady Jane! Could our eyes pierce yon stone walls,” he added, pointing to the Brick Tower, “I make no doubt we should discover her on her knees. She passes most of her time, I am informed, in prayer.”

“Humph!” ejaculated Renard. And he half muttered, “She shall either embrace the Romish faith, or die by the hand of the executioner.”

Winwike made no answer to the observation, and affected not to hear it, but he shuddered at the look that accompanied it—a look that brought to mind all he heard of the mysterious and terrible individual at his side.

By this time, the sun was high in heaven, and the whole fortress astir. A flourish of trumpets was blown on the Green, and a band of minstrels issued from the portal of the Coalharbour Tower. The esquires, retainers, pages, and servitors of the various noblemen, lodged within the palace, were hurrying to and fro, some hastening to their morning meal, others to different occupations. Everything seemed bright and cheerful. The light laugh and the merry jest reached the ear of the listeners. Rich silks and costly stuffs, mixed with garbs of various-coloured serge, with jerkins and caps of steel, caught the eye. Yet how much misery was there near this smiling picture! What sighs from those in captivity responded to the shouts and laughter without! Queen Mary arose and proceeded to matins in Saint John’s Chapel. Jane awoke and addressed herself to solitary prayer; while Northumberland, who had passed a sleepless night, pacing his dungeon like a caged tiger, threw himself on his couch, and endeavoured to shut out the light of day and his own agonizing reflections.

Meanwhile, Renard and the warder had descended from the White Tower and proceeded to the Green.

“Who is that person beneath the Beauchamp Tower gazing so inquisitively at its barred windows?” demanded the former.

“It is the crow scenting the carrion—it is Mauger the headsman,” answered Winwike.

“Indeed?” replied Renard; “I would speak with him.”