Several days having elapsed since the trial, and no order made for his execution, the Duke of Northumberland, being of a sanguine temperament, began to indulge hopes of mercy. With hope, the love of life returned, and so forcibly, that he felt disposed to submit to any humiliation to purchase his safety. During this time, he was frequently visited by Bishop Gardiner, who used every persuasion to induce him to embrace the Romish faith. Northumberland, however, was inflexible on this point, but, professing the most, sincere penitence, he besought the Bishop, in his turn, to intercede with the Queen in his behalf. Gardiner readily promised compliance, in case his desires were acceded to; but as the Duke still continued firm in his refusal, he declined all interference. “Thus much I will promise,” said Gardiner, in conclusion; “your grace shall have ample time for reflection, and if you place yourself under the protection of the Catholic church, no efforts shall be wanting on my part to move the Queen’s compassion towards you.”

That night, the officer on guard suddenly threw open the door of his cell, and admitting an old woman, closed it upon them. The Duke, who was reading at the time by the light of a small lamp set upon a table, raised his eyes and beheld Gunnora Braose.

“Why have you come hither?” he demanded. “But I need no task. You have come to gratify your vengeance with a sight of my misery. Now you are satisfied, depart.”

“I am come partly with that intent, and partly with another,” replied Gunnora. “Strange as it may sound, and doubtful, I am come to save you.”

“To save me!” exclaimed Northumberland, starting. “How?—But—no!—no! This is mockery. Begone, accursed woman.”

“It is no mockery,” rejoined Gunnora. “Listen to me, Duke of Northumberland. I love vengeance well, but I love my religion better. Your machinations brought my foster-son, the Duke of Somerset, to the block, and I would willingly see you conducted thither. But there is one consideration that overcomes this feeling. It is the welfare of the Catholic church. If you become a convert to that creed, thousands will follow your example; and for this great good I would sacrifice my own private animosity. I am come hither to tell you your life will be spared, provided you abandon the Protestant faith, and publicly embrace that of Rome.”

“How know you this?” demanded the Duke.

“No matter,” replied Gunnora. “I am in the confidence of those, who, though relentless enemies of yours, are yet warmer friends to the Church of Rome.”

“You mean Simon Renard and Gardiner!” observed Northumberland.

G minora nodded assent.

“And now my mission is ended,” she said. “Your grace will do well to weigh what I have said. But your decision must be speedy, or the warrant for your execution will be signed. Once within the pale of the Catholic church, you are safe.”

“If I should be induced to embrace the offer!” said the Duke. “If”—cried Gunnora, her eye suddenly kindling with vindictive fire.

“Woman,” rejoined the Duke, “I distrust you. I will die in the faith I have lived.”

“Be it so,” she replied. “I have discharged the only weight I had upon my conscience, and can now indulge my revenge freely. Farewell! my lord. Our next meeting will be on Tower Hill.”

“Hold!” cried Northumberland. “It may be as you represent, though my mind misgives me.”

“It is but forswearing yourself,” observed Gunnora, sarcastically. “Life is cheaply purchased at such a price.”

“Wretch!” cried the Duke. “And yet I have no alternative. I accede.”

“Sign this then,” returned Gunnora, “and it shall be instantly conveyed to her highness.”

Northumberland took the paper, and casting his eye hastily over it, found it was a petition to the Queen, praying that he might be allowed to recant his religious opinions publicly, and become reconciled to the church of Rome. “It is in the hand of Simon Renard,” he observed.

“It is,” replied Gunnora.

“But who will assure me if I do this, my life will be spared!”

“I will,” answered the old woman.

“You!” cried the Duke.

“I pledge myself to it,” replied Gunnora. “Your life would be spared, even if your head were upon the block. I swear to you by this cross,” she added, raising the crucifix that hung at her neck, “if I have played you falsely, I will not survive you.”

“Enough,” replied the Duke, signing the paper.

“This shall to the Queen at once,” said Gunnora, snatching it with a look of ill-disguised triumph. “To-morrow will be a proud day for our church.”

And with this she quitted the cell.

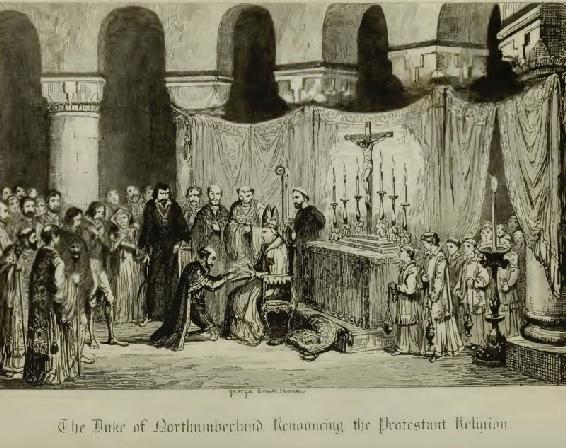

The next morning, the Duke was visited by Gardiner, on whose appearance he flung himself on his knees. The bishop immediately raised him, and embraced him, expressing his delight to find that he at last saw through his errors. It was then arranged that the ceremonial of the reconciliation should take place at midnight in Saint John’s Chapel in the White Tower. When the Duke’s conversion was made known to the other prisoners, the Marquess of Northampton, Sir Andrew Dudley, (Northumbcrland’s brother,) Sir Henry Gates, and Sir Thomas Palmer; they all—with the exception of the Earl of Warwick, who strongly and indignantly reprobated his father’s conduct,—desired to be included in the ceremonial. The proposal being readily agreed to, priests were sent to each of them, and the remainder of the day was spent in preparation for the coming rites.

At midnight, as had been arranged, they were summoned. Preceded by two priests, one of whom bore a silver cross, and the other a large flaming wax candle, and escorted by a band of halberdiers, carrying lighted torches, the converts proceeded singly, at a slow pace, across the Green, in the direction of the White Tower. Behind them marched the three gigantic warders, Og, Gog, and Magog, each provided with a torch. It was a solemn and impressive spectacle, and as the light fell upon the assemblage collected to view it, and upon the hoary walls of the keep. The effect was peculiarly striking. Northumberland walked with his arms folded, and his head upon his breast, and looked neither to the right nor to the left.

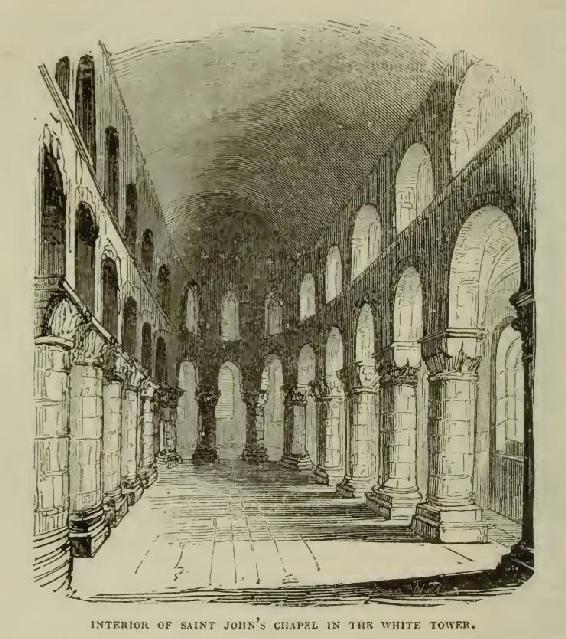

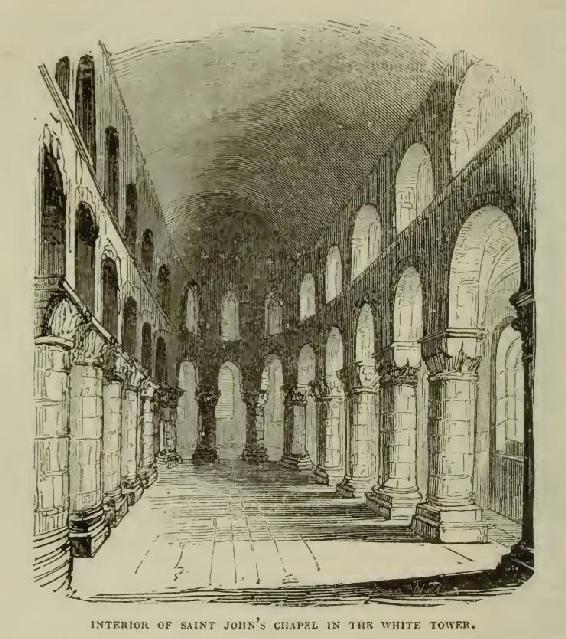

Passing through Coalharbour Gate, the train entered an arched door-way in a structure then standing at the south-west of the White Tower. Traversing a long winding passage, they ascended a broad flight of steps, at the head of which was a gallery leading to the western entrance of the chapel. Here, before the closed door of the sacred structure, beneath the arched and vaulted roof, surrounded by priests and deacons in rich copes, one of whom carried the crosier, while others bore silver-headed staves, attired in his amice, stole, pluvial and alb, and wearing his mitre, sat Gardiner upon a faldstool. Advancing slowly towards him, the Duke fell upon his knees, and his example was imitated by the others. Gardiner then proceeded to interrogate them in a series of questions appointed by the Romish formula for the reconciliation of a heretic; and the profession of faith having been duly made, he arose, took off his mitre, and delivering it to the nearest priest, and extended his arms over the converts, and pronounced the absolution. With his right thumb he then drew the sign of the cross on the Duke’s forehead, saying, “Accipe signum crucis.” and being answered, “Acccpi.” he went through the same form with the rest. Once more assuming the mitre, with his left hand he took the Duke’s right, and raised him, saying, “Ingredere in ceclesiam Dei à qua incaute alerrasti. Horicsce idola. Respite omnes gravitates et super superstitiones hereticus. Cole Deum oninipotcntem et Jesum fillimm ejus, et Spiritum Sanctum.”

Upon this, the doors of the chapel were thrown open, and the bishop led the chief proselyte towards the altar. Against the massive pillars at the east end of the chapel, reaching from their capitals to the base, was hung a thick curtain of purple velvet, edged with a deep border of gold. Relieved against this curtain stood the altar, covered with a richly-ornaincnted antipendium, sustaining a large silver crucifix, and six massive candlesticks of the same metal. At a few paces from it, on either side, were two other colossal silver candlesticks, containing enormous wax lights. On either side were grouped priests with censers, from which were diffused the most fragrant odours.

As Northumberland slowly accompanied the bishop along the nave, he saw, with some misgiving, the figures of Simon Renard and Gunnora emerge from behind the pillars of the northern aisle. His glance met that of Renard, and there was something in the look of the Spaniard that made him fear he was the dupe of a plot—but it was now too late to retreat. When within a few paces of the altar, the Duke again knelt down, while the bishop removed his mitre as before, and placed himself in front of him.

Meanwhile, the whole nave of the church, the aisles, and the circular openings of the galleries above, were filled with spectators. A wide semicircle was formed around the converts. On the right stood several priests. On the left Simon Renard had planted himself, and near to him stood Gunnora; while, on the same side against one of the pillars, was reared the gigantic frame of Magog. A significant look passed between them as Northumberland knelt before the altar. Extending his arms over the convert, Gardiner now pronounced the following exhortation:— “Omnipotens sempiterne Deus hanc ovem tuam de faucibus lupi tua virtute subtractam paterna recipe, pietate et gregi tuo reforma piâ benignitate ne de familiâ tua damno inimicus exultet; sed de conversione et liberatione jus ecclesiam ut pia mater de filio reperto gratuletur per Christum Dominum nostrum.”

“Amen!” ejaculated Northumberland.

After uttering another prayer, the bishop resumed his mitre, and seating himself upon the faldstool, which, in the interim, had been placed by the attendants in front of the altar, again interrogated the proselyte:—

“Homo, abrcnuncias Sathanas et angelos ejus?”

“Abrenuncio,” replied the Duke.

“Abrenuncias etiam omnes sectas hereticæ pravitatis?” continued the bishop.

“Abrenuncio,” responded the convert.

“Vis esse et vivere in imitate sancto fidei Catholico?” demanded Gardiner.

“Volo,” answered the Duke.

Then again taking off his mitre, the bishop arose, and laying his right hand upon the head of the Duke, recited another prayer, concluding by signing him with the cross. This done, he resumed his mitre, and seated himself on the faldstool, while Northumberland, in a loud voice, again made a profession of his faith, and abjuration of his errors—admitting and embracing the apostolical ecclesiastical traditions, and all others—acknowledging all the observances of the Roman church——purgatory—the veneration of saints and relics—the power of indulgences—promising obedience to the Bishop of Rome,—and engaging to retain and confess the same faith entire and invio-lated to the end of his life. “Ago talis,” he said, in conclusion, “cognoscens veram Catholicam et Apostolicum fidem. Anathematizo hic publiée omnem heresem, procipuè illam de qua hactenus extiti.” This he affirmed by placing both hands upon the book of the holy gospels, proffered him by the bishop, exclaiming, “Sic me Deus adjunct, et hoc sancta Dei evangelia!”

The ceremony was ended, and the proselyte arose. At this moment, he met the glance of Renard—that triumphant and diabolical glance—its expression was not to be mistaken. Northumberland shuddered, he felt that he had been betrayed.