Charged with the painful and highly-responsible commission imposed upon him by the queen, Sir Henry Bedingfeld, accompanied by the Earl of Sussex and three others of the council, Sir Richard Southwell, Sir Edward Hastings, and Sir Thomas Cornwallis, with a large retinue, and a troop of two hundred and fifty horse, set out for Ashbridge, where Elizabeth had shut herself up previously to the outbreak of Wyat’s insurrection. On their arrival, they found her confined to her room with real or feigned indisposition, and she refused to appear; but as their mission did not admit of delay, they were compelled to force their way to her chamber. The haughty princess, whose indignation was roused to the highest pitch by the freedom, received them in such manner as to leave no doubt how she would sway the reins of government, if they should ever come within her grasp.

“I am guiltless of all design against my sister,” she said, “and I shall easily convince her of my innocence. And then look well, sirs—you that have abused her authority—that I requite not your scandalous treatment.”

“I would have willingly declined the office,” replied Bedingfeld; “but the queen was peremptory. It will rejoice me to find you can clear yourself with her highness, and I am right well assured, when you think calmly of the matter, you will acquit me and my companions of blame.”

And he formed no erroneous estimate of Elizabeth’s character. With all her proneness to anger, she had the strongest sense of justice. Soon after her accession, she visited the old knight at his seat, Oxburgh Hall, in Norfolk;—still in the possession of his lineal descendant, the present Sir Henry Bedingfeld, and one of the noblest mansions in the county,—and, notwithstanding his adherence to the ancient faith, manifested the utmost regard for him, playfully terming him “her jailor.”

Early the next morning, Elizabeth was placed in a litter, with her female attendants; and whether from the violence of her passion, or that she had not exaggerated her condition, she swooned, and on her recovery appeared so weak that they were obliged to proceed slowly. During the whole of the journey, which occupied five days, though it might have been easily accomplished in one, she was strictly guarded;—the greatest apprehension being entertained of an attempt at rescue by some of her party. On the last day, she robed herself in white, in token of her innocence; and on her way to Whitehall, where the queen was staying, she drew aside the curtains of her litter, and displayed a countenance, described in Renard’s despatches to the Emperor, as “proud, lofty, and superbly disdainful,—an expression assumed to disguise her mortification.” On her arrival at the palace, she earnestly entreated an audience of her majesty, but the request was refused.

That night Elizabeth underwent a rigorous examination by Gardiner and nineteen of the council, touching her privity to the conspiracy of De Noailles, and her suspected correspondence with Wyat. She admitted having received letters from the French ambassador on behalf of Courtenay, for whom, notwithstanding his unworthy conduct, she still owned she entertained the warmest affection, but denied any participation in his treasonable practices, and expressed the utmost abhorrence of Wyat’s proceedings. Her assertions, though stoutly delivered, did not convince her interrogators, and Gardiner told her that Wyat had confessed on the rack that he had written to her, and received an answer.

“Ah! says the traitor so?” cried Elizabeth. “Confront me with him, and if he will affirm as much to my face, I will own myself guilty.”

“The Earl of Devonshire has likewise confessed, and has offered to resign all pretensions to your hand, and to go into exile, provided the queen will spare his life,” rejoined Gardiner.

“Courtenay faithless!” exclaimed the princess, all her haughtiness vanishing, and her head, declining upon her bosom, “then it is time I went to the Tower. You may spare yourselves the trouble of questioning me further, my lords, for by my faith I will not answer you another word—-no, not even if you employ the rack.”

Upon this, the council departed. Strict watch was kept over her during the night. Above a hundred of the guard were stationed within the palace-gardens, and a great fire was lighted in the hall, before which Sir Henry Bedingfeld and the Earl of Sussex, with a large band of armed men, remained till day-breaks At nine o’clock, word was brought to the princess that the tide suited for her conveyance to the Tower. It was raining heavily, and Elizabeth refused to stir forth on the score of her indisposition. But Bedingfeld told her the queen’s commands were peremptory, and besought her not to compel him to use force. Seeing resistance was in vain, she consented with an ill grace, and as she passed through the garden to the water-side, she cast her eyes towards the windows of the palace, in the hope of seeing Mary, but was disappointed.

The rain continued during the whole of her passage, and the appearance of every thing on the river was as dismal and depressing as her own thoughts. But Elizabeth was not of a nature to be easily subdued. Rousing all her latent energy, she bore up firmly against her distress. An accident had well nigh occurred as they shot London Bridge. She had delayed her departure so long that the fall was considerable, and the prow of the boat struck upon the ground with such force as almost to upset it, and it was some time before it righted. Elizabeth was wholly unmoved by their perilous situation, and only remarked that “She would that the torrent had sunk them.” Terrible as the stern old fortress appeared to those who approached it under similar circumstances, to Elizabeth it assumed its most appalling aspect. Gloomy at all times, it looked gloomier than usual now, with the rain driving against it in heavy scuds, and the wind, whistling round its ramparts and fortifications, making the flag-staff and the vanes on the White Tower creak, and chilling the sentinels exposed to its fury to the bone. The storm agitated the river, and the waves more than once washed over the sides of the boat.

“You are not making for Traitors Gate,” cried Elizabeth, seeing that the skiff was steered in that direction; “it is not fit that the daughter of Henry the Eighth should land at those steps.”

“Such are the queen’s commands,” replied Bedingfeld, sorrowfully. “I dare not for my head disobey.”

“I will leap overboard sooner,” rejoined Elizabeth.

“I pray your highness to have patience,” returned Bedingfeld, restraining her. “It would be unworthy of you—of your great father, to take so desperate a step.”

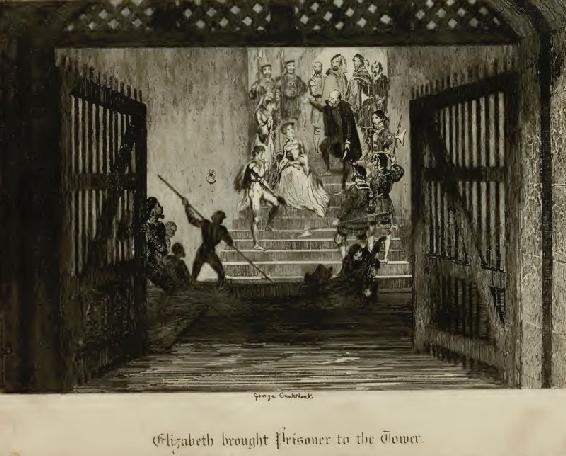

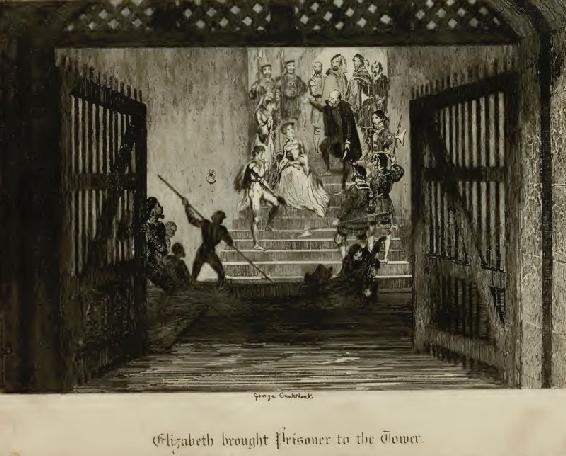

Elizabeth compressed her lips and looked sternly at the old knight, who made a sign to the rowers to use their utmost despatch; and, in another moment, they shot beneath the gloomy gateway. The awful effect of passing under this dreadful arch has already been described, and Elizabeth, though she concealed her emotion, experienced its full horrors. The Water-gate revolved on its massive hinges, and the boat struck against the foot of the steps. Sussex and Bedingfeld, and the rest of the guard and her attendants, then landed, while Sir Thomas Brydges, the new lieutenant, with several warders, advanced to the top of the steps to receive her. But she would not move, but continued obstinately in the boat, saying, “I am no traitor, and do not choose to land here.”

“You shall not choose, madam,’” replied Bedingfeld, authoritatively. “The queen’s orders must, and shall be obeyed. Disembark, I pray you, without more ado, or it will go hardly with you.”

“This from von, Bedingfeld,” rejoined Elizabeth, reproachfully, “and at such a time, too?”

“I have no alternative,’” replied the knight.

“Well then, I will not put you to further shame,” replied the princess, rising.

“Will it please you to take my cloak as a protection against the rain?” said Bedingfeld, offering it to her. But she pushed it aside “with a good dash,” as old Fox relates; and springing on the steps, cried in a loud voice, “Here lands as true a subject, being prisoner, as ever set foot on these stairs. And before thee, O God, I speak it, having no other friend but thee.” *

“Your highness is unjust,” replied Bedingfeld, who stood bare-headed beside her; “you have many friends, and amongst them none more zealous than myself. And if I counsel you to place some restraint upon your conduct, it is because I am afraid it may be disadvantageous reported to the queen.”

“Say what you please of me, sir,” replied Elizabeth; “I will not be told how I am to act by you, or any one.”

“At least move forward, madam,” implored Bedingfeld; “you will be drenched to the skin if you tarry here longer, and will fearfully increase your fever.”

“What matters it if I do?” replied Elizabeth, seating herself on the damp step, while the shower descended in torrents upon her. “I will move forward at my own pleasure—not at your bidding. And let us see whether you will dare to use force towards me.”

“Nay, madam, if you forget yourself, I will not forget what is due to your father’s daughter,” replied Bedingfeld, “you shall have ample time for reflection.”

The deeply-commiserating and almost paternal tone in which this reproof was delivered touched the princess sensibly; and glancing round, she was further moved by the mournful looks of her attendants, many of whom were deeply affected, and wept audibly. As soon as her better feelings conquered, she immediately yielded to them; and, presenting her hand to the old knight, said, “You are right, and I am wrong, Bedingfeld. Take me to my dungeon.”