Chapter 6

New People in Old Buildings

The thing to keep in mind is that a new culture is emerging…The people in this new culture cannot live within the space of the old car-oriented lifestyle. It is a period of transition…Instead of driving out to the suburbs to look for things to do and things to buy, they’ll be able to find it in their own neighborhood. And when a person gets home from work, they won’t feel like sitting in the living room and watching TV; they’ll be able to walk down the street and visit the crafts shops or watch an artist painting. And a lot of people are concerned about crime; I’ve always felt the best way to prevent crime is to get people out onto the streets, get life out onto the street.

—Sal Yniguez100

Between 1950 and 1970, Sacramento’s central city lost thirty thousand people. As the western half of the city was demolished, the eastern half remained mostly intact. Many of the early plans for redevelopment envisioned continued demolition and redevelopment all the way east to Alhambra Boulevard, replacing the central city’s homes with apartment buildings and commercial offices, sparing only a few of the most architecturally significant examples of nineteenth-century architecture. As money and political will for redevelopment ran out, large-scale demolition slowed. Repeal of Proposition 14 made racial exclusion covenants, opening more suburban neighborhoods for nonwhites. Banks still refused loans to redlined neighborhoods until the mid-1970s, making new construction or home renovation in the Old City difficult.101

As the World War II generation settled down in the suburbs, a new generation of Sacramentans started returning to the Old City. Some were artists seeking cheap rent and others of similar mindset, actors and musicians seeking places to play. Some were drawn to the beauty of the old city’s residential architecture and the diversity and walkability of the neighborhood when compared to the suburbs where they grew up. Many were public employees uninterested in commuting to work from the suburbs, including the highest-ranking public employee in the state, young Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown, who rejected the suburban mansion built for the Reagans in favor of an apartment across the street from Capitol Park. The redevelopment zone and K Street Mall had little appeal for this generation, who created their own businesses, restaurants, art galleries, community organizations and newspapers to celebrate the rebirth of a neighborhood. By 1980, the population of the central city grew for the first time in thirty years.

Protesters at the California State Capitol speak out against the Vietnam War, May 8, 1970. The Capitol was a frequent site of antiwar protests and civil rights marches. Center for Sacramento History.

THE BEGINNING

Sacramento native Mickey Abbey described his childhood as trouble-free. Born in 1943, he grew up in Colonial Heights, a working-class neighborhood along Stockton Boulevard. After attending Sacramento City College he decided it was time to leave town. Following a girlfriend to San Francisco, he attended SFSU studying art and got a job for Macy’s and Joseph Magnin’s creating window displays. He rented a storefront with living quarters in the back on Church and Army Streets just in time for the Summer of Love:

When I was down there it was freewheeling, wide open, everything was new, fresh, it didn’t seem like there were any rules. Every day was a new day, even at work, so it was fantastic…I already was kind of into that storefront studio/party room kind of a social space. If you imagine a whole storefront you can imagine the groups and the parties. Of course the whole crowd was the art crowd, we used it for all kinds of stuff, mini plays, mini shows, put on a show in the storefront there. We used it as the studio and we could transform it into a gallery in a short time. We shared it with all of our art friends. We had a raised area in the back of the store that we used as a living room and then it became a stage on occasion. It was like being in a theater, you just changed the scenery…I worked with a couple of people called “Wiggy Rings.” At the Alameda flea market you could buy a shoebox full of Grandma’s jewelry, costume jewelry, for ten to fifteen dollars, and we’d take this costume jewelry, dump it on the table and we would disassemble it and reassemble it into big bodacious rings that we could sell at the shops down in the Haight area—we were making extra money that way. There weren’t a lot of craft fairs back then, but there were a lot of shops, or you just set up a corner on the street, throw out a card table and you’re in business.

By 1968, the Summer of Love was fading. Rents got higher, drugs got harder and people started moving out. Mickey decided to move back to Sacramento but took his San Francisco experience with him. Teaming up with a pair of his old friends, woodworker Bob Lipelt and metalsmith Rick Ball, the trio started hunting for a retail space like Mickey’s spot on Church and Army Streets. In late 1969, Bob’s wife, Rose, found a store for rent on L Street between 17th and 18th. The storefront was a stucco and tile addition to an old Victorian home, a former laundry in between Earl’s Barbershop and Mario’s Italian Cellar. Rent was $125 a month, with enough space in the back for a workshop. The building was owned by Al Nielsen of the nearby Nielsen Tire Company. Mickey was unsure how Nielsen would respond to a trio of “long-haired, dope smoking hippies,” but Nielsen quickly agreed.

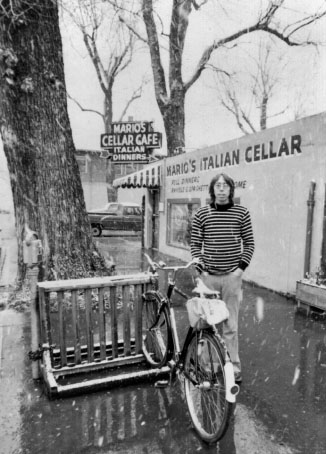

Rick Ball and Bob Lipelt in front of the Beginning, 17th and L Streets, circa 1970–75. Mickey Abbey.

The trio went to work, decorating the workshop with rustic barn wood and outfitting the back room into a work space and living quarters for Mickey and Rick. By 1970, the shop opened, named the Beginning. Shortly afterward, the Japanese family who had operated the laundry moved out of the Victorian home, and a group of Mickey’s friends moved in. All three artists had their specialties, Mickey with stained glass, Bob with wood and Rick with brass, but all experimented with other media based on what people asked for and what sold. Mickey recalled that one of the most popular items in the early days of the Beginning were sand candles, made by pouring wax into molds of wet sand.

At first, the store had trouble getting enough business to pay the $125 a month rent. Mickey parlayed his previous experience with window displays into a display job at Weinstock’s, supplementing the rent, but the focus of the Beginning was art, creativity and social space, not profits. Like his San Francisco shop, parties were a regular part of the Beginning, featuring a mixture of artists, crafters and creative community, like a new generation’s version of the Belmonte Gallery beatnik scene, but Mickey considered the hippies of the early 1970s more spirited and playful than the serious, poetry-obsessed Beats, in addition to having a more colorful wardrobe. A parking lot next door was frequently used as an impromptu skating rink using skates from the High Rollers shop, with music provided by the Nate Shiner Band or other downtown musicians. On the opposite corner of 18th and L Streets, an entire city block sat vacant, the former home of Sacramento High School, later Sutter Middle School, until its demolition in 1959. This lot was sometimes the site of impromptu community picnics and a frequent staging area for downtown parades. Benches in front of the Beginning provided an ideal perch to watch the parades go by, but even when the circus wasn’t in town, it became a location of choice to watch the parade of the streets.

The scene in front of the Beginning. Left to right: Richad McCracken, Twinka Thiebaud (daughter of artist Wayne Thiebaud), Rick Ball, Mickey Abbey, Ron Hernandez and Bob Lipelt. Mickey Abbey.

The interior décor of the Beginning changed over time, starting with rustic barn wood but enhanced later by additions of stained glass and antique and custom-made furniture. Often, they made use of foraged and reused materials. An old Coke machine became the Beginning’s refrigerator. A medical skeleton was frequently posed around the store, lounging on couches or chairs, playing a stand-up piano in the back or relaxing inside a coffin that Mickey often used for a bed. Many visitors to the Beginning were inspired to take the same leap and open their own shops nearby.102

Juliana’s Kitchen was Sacramento’s first health food restaurant, located on 17th and L Streets in the early 1970s. Mickey Abbey’s stained glass decorated the windows. Diane Heinzer.

Within a few years, more counterculture and hippie-run businesses started moving into the neighborhood. When Earl the barber retired, Steven Ballew and graphic designer Bob Rakela opened up a roller skate shop next door. Another art gallery, Lhasa Hook, opened on the opposite side of L Street. At the corner of 18th and L, leatherworker Hank Sanders opened a shop selling custom-made sandals and moccasins. His shop was short-lived, replaced by Juliana’s Kitchen, an organic restaurant with vegetarian options, yogurt, granola, whole-grain breads, sprouts, garden salads, fresh organic juices and natural cheeses.

Other counterculture shops and galleries opened for business in the neighborhood, including Failasouf, a “head shop” at 22nd and K Streets owned by a belly dancer named Jodette, selling incense, clothes, psychedelic posters, pipes and other paraphernalia of youth culture, although another head shop, the Eye, had opened on 14th and K Streets in 1967. At 15th and P Streets, the Real Food Company opened for business in 1973 in the old Fremont Cash Grocery, selling organic produce, bulk tea, grains and beans, later becoming the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-Op at a larger location on Freeport Boulevard. Artist Bill Dalton opened a gallery in a warehouse on 10th and R Streets before moving into a vacant space in the old Fred David Candy Company, founding an English-style pub called Fox & Goose. Within the same complex of buildings, a whole cluster of small shops opened, including Sunrise Leather, Arareity Jewelers, Earthworks ceramic store and Rumplestilkstin, a weaving and fabric supply store. A short-lived attempt to create a similar collective in a garage at 16th and F Streets, the Arts and Crafts Guild, encountered resistance from city building inspectors, who closed the Guild’s door just a few months after it opened. Despite occasional official resistance, hippie craft shops and art galleries flourished, thanks to cheap rent, relatively little competition and a growing customer base of young people.103

Artisan & Craftsmen was a short-lived craft bazaar on 16th and F Streets containing multiple stalls and displaying the work of many local crafters. The City of Sacramento shut down the facility shortly after it opened in December 1974. Steve Ballew is fifth from the right in turtleneck and black hat. Mickey Abbey.

SUTTERTOWN NEWS

In 1975, another neighbor moved into the corner of 18th and L Street, intent on spreading the word about the exciting changes he saw in Sacramento. Tim Holt was born in Sacramento in 1948, and like Mickey Abbey, he grew up in Sacramento’s southern suburbs, near Sutterville Road and Land Park. As a teenager, he spent time in Oak Park, sipping espresso at the Belmonte Gallery and watching European films at the Guild Theatre. In high school, he became disenchanted with Sacramento’s cultural limitations and what he saw as constraints on youth culture:

At that time we had a county sheriff named John Misterly, and he felt, maybe with some justification, that if you got more than three to four teenagers together at something like a dance, there would be trouble. So he was really against having, essentially, gathering events for teenagers. So, as you well know, what we had was cruising K Street and going to the movies, and that was pretty much it. It just seemed like it was a little difficult to find things to do as a teenager in Sacramento. So I was very happy to leave when I was eighteen, graduated from McClatchy High School. I went to Berkeley for my undergraduate years, a whole new environment I really enjoyed, to be honest.

As I say, in all fairness to the guy, I would not be surprised if there had not been some wild—they used to have dances in Governor’s Hall, which was on the old state fairgrounds on Stockton Boulevard. I have a feeling some of those dances may have gotten out of hand, and why Sheriff Misterly decided there would not be any more such, at least for a while…I came back to Sacramento in the summer of 1974; I had been gone about eight years. I had been writing for various publications in the Bay Area. The editor of San Francisco Magazine said, “Why don’t you go back to your hometown and start a newspaper?” almost out of the blue. I thought it was a crazy idea, but it kind of grew on me. I had decided on a career in journalism by then, and it just started to take hold. My personal journey as a journalist was part of it, but it was also joining that personal journey with the new things that were happening in downtown Sacramento.

Launched on March 21, 1975, Tim Holt’s Suttertown Good-Time News (later shortened to Suttertown News) was based in a second-story office at 18th and L Streets, across from Juliana’s Kitchen and the Beginning. The first issue was a single sheet of newsprint. A story on local restaurants entitled “Cheap Eats” included Juliana’s, Jim-Denny’s, the 524 Club, Katetsu Japanese, the Fox & Goose and the sandwich counter at Jenovino’s grocery store, a cross-section of the city’s culinary diversity. Contributor Lou Thelen documented the United Farm Workers’ boycott of Gallo Winery, led by Cesar Chavez, ending the story by noting how the Sacramento Bee placed a small story about the march directly across from a full-page Gallo advertisement and the Union did not cover the protest at all, other than a small story via the UPI wire service the following day. Suttertown News was a neighborhood newspaper, but a neighborhood like downtown Sacramento, the heart of California’s political arena, meant that stories were not limited to feel-good local fare. Holt announced his newspaper’s intent in a “Declaration of Interdependence”:

Sacramento Real Food Company, founded in 1973, was an organic food co-op based out of the old Enos Grocery Store at 1500 Q Street. It later became the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-Op. Mickey Abbey.

Something is happening in Sacramento. Little by little, we see a new community taking shape within the confines of the downtown area. We call this new community “Suttertown,” and it is not so much a geographic place as a state of mind. To get a feeling for Suttertown, take your mind back a few decades. Imagine what it was like to stroll from one end of town to the other in full view of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, without having to dodge cars or breathe exhaust fumes. Instead of hearing auto engines or police sirens, you’d hear the clomping of horses, hooves, the ring of a blacksmith’s anvil, the sound of a saw as it bites into wood. In this town, in John Sutter’s day, men made their living by the labor of their hands.

Such a town exists. The “rebirth” of Suttertown began in 1970, when Mickey Abbey, Robert Lipelt, and Rick Ball opened The Beginning, a combination workshop and crafts store at 18th and L Street. Two similar ventures, Down Home and The Guild Store, were launched shortly thereafter. Suttertown exists, too, on a square block of land at 14th and Q streets, where men and women, young and old alike, grow vegetables for their tables. Suttertown is alive and growing in the residential districts, where many of the fine old Victorians are being shined up and refurbished. And, as of this day, Suttertown has a new addition, something important to the life of any community. It has a newspaper.104

THE “CALIFORNIA STATE CAPITOL PLAN” CHANGES PLANS

In January 1976, Dennis Bylo arrived in Sacramento to complete his internship, the final step before receiving his master’s degree in architecture from UC Berkeley. Born in Los Angeles in 1945, Dennis studied art and environmental design at UCLA. His only previous trip to Sacramento was in 1972 for a hearing regarding his honorable discharge from the air force as a conscientious objector after piloting C141 Starlifters. Along with four other interns, he worked under California state architect Sim van der Ryn, urban planner Peter Calthorpe and a team assigned by Governor Jerry Brown to update the California State Capitol Plan.

The California State Capitol Plan, first enacted in 1960 by Brown’s father, was separate from the redevelopment projects along Capitol Mall but followed a similar pattern. The city’s redevelopment zones south of Capitol Mall were west of 7th Street, leaving the area south of N Street relatively untouched. Sacramento’s long-range general plan called for a larger-scale reshaping of the Old City, but even federally funded redevelopment plans had their limits. Long-range estimates predicted California’s population would grow to between forty and sixty million people by 2010, requiring an enormous future investment in state offices. The State Capitol Plan, passed by the legislature, set aside state funds to acquire all the privately owned land between 7th and 17th Streets south to Q Street, demolishing all but a handful of buildings (the Stanford and Heilbron mansions, the Presbyterian church, two apartment buildings and the new El Mirador Hotel on N Street) and turning the entire expanse into a gigantic complex of state buildings. The only new housing envisioned by the plan was a new governor’s residence to replace the old Gallatin mansion. The legislature approved $35 million in state funds to acquire the land and immediately began demolishing blocks to clear the way for the new complex. Because these were state funds, not federal, the 1964–67 moratorium on federal redevelopment funds did not affect the State Capitol Plan.105

The Leland B. Stanford Mansion at 8th and N Streets was one of three surviving West End mansions, along with the Crocker and Heilbron Mansions. In this circa 1970 photo, the Stanford Mansion is flanked by a parking lot and an office building, the fate of nearly every West End home. Author’s collection.

Demolition swept away almost every resident of the neighborhood. Census Tract 9, between Capitol and R Streets from 7th to 12th, dropped from almost 1,500 people in 1960 to only 121 in 1970. Tract 13, between Capitol and R from 12th to 21st, lost 1,500 people but remained highly populated due to construction of many new apartment buildings on the tract’s eastern edge. In 1968, according to Bylo, “Reagan came in and continued the acquisition of the land under the 1960 plan, continued demolishing all the housing, turning the land into surface parking lots, and put all the offices out in the county where his buddies were.” Reagan had already abandoned the old governor’s mansion for a house in East Sacramento and planned a new official residence in Carmichael.106

When Jerry Brown took over the governor’s office from Reagan in 1972, he was just as uninterested in a suburban mansion as Reagan had been in the old house on H Street. Instead of an opulent governor’s residence, Brown moved into the Dean Apartments, one of the few surviving buildings in the State Capitol Plan area. He assigned Sim van der Ryn, a pioneer of sustainable design and energy-efficient architecture, the task of creating a new Capitol Area Plan based on a new generation of planners’ ideas about cities. Planners like van der Ryn and Calthorpe were influenced by writers like Jane Jacobs, whose influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities challenged the highway-centric approach to redevelopment that depopulated city centers and displaced their residents. Jacobs advocated mixed use, walkability and residential density, opposed highways and single-use redevelopment and encouraged pedestrian activity and streetscape. In short, the new vision for American cities resembled neighborhoods like the West End, only a few years after the dust of their demolition had settled.

The new plan, retitled the Capitol Area Plan, was based on a mixture of housing, local stores and workplaces explicitly intended to re-create some of the aspects of the lost West End and complement the surviving central city neighborhoods. The new neighborhood plans combined office, retail and residential uses on each block, the opposite of the single-use zoning approach of the original plan. More housing in mid-rise and moderate-density units near state offices, located near the planned light rail line, reduced the need for the blocks of city-killing parking lots by reducing the number of automobile-based commuters. Passive solar and climate-responsive building designs reduced energy consumption. Instead of disrupting Sacramento’s traditional grid street pattern with superblocks and boulevards, the revised plan reinforced it, as one of Jacobs’s main lessons was the importance of a permeable street grid.

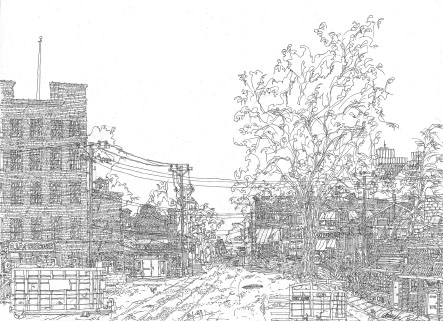

R Street, a railroad route and industrial corridor, was the site of early 1970s businesses like the Fox & Goose restaurant, Arareity jewelry stores and other craft businesses in the former David Candy Company building, captured by architect/artist Dennis Bylo. Dennis Bylo.

The new plan made use of already-constructed portions of the old plan and surviving apartment buildings within the plan boundary. New construction included the Somerset Parkside condominiums, a mixed-use complex that introduced another feature of the new plan: mixed-income housing. One-third of the project was intended for individuals with low incomes, one-third for middle incomes and one-third at market rate. This mixture of affordability was intended to address the loss of affordable housing in the central city and limit the effects of gentrification that drove low-income individuals out of city centers as rents increased. Office buildings designed during this era made use of active and passive means of energy conservation, including a mostly subterranean building that utilized geothermal energy for temperature control, with a “green roof” on top serving as a semi-public park. This subterranean “bunker” also allowed sunlight to strike solar collectors on an adjacent state building.107

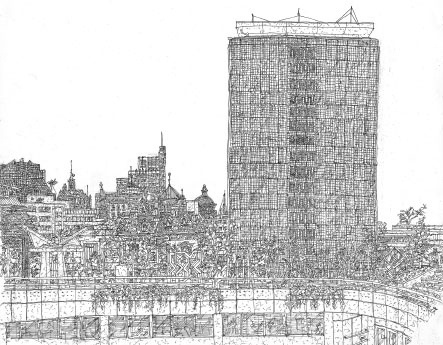

This sketch was drawn from a state office at 9th and O Streets, built partially underground to allow light to strike a solar power array on an adjacent building. This building also featured a rooftop garden, amphitheater and free-form sculpture. Drawing by Dennis Bylo.

Dennis and the other interns were assigned to survey the existing inventory of the neighborhood. While he enjoyed the work and was hired as a consultant for six months after completing his internship, he saw serious flaws in the plan. The plan was designed to be flexible but with so much flexibility that it became easy for stage agencies to ignore the guidelines. Management of apartments in the plan area was a major problem, leading Dennis and other tenants to call a rent strike to protest rent increases and poor maintenance. He recalled:

In the process of the state buying up the neighborhood, the properties would be immediately leased back to the former owner, and the former owner was responsible for maintaining the properties, fixing the small stuff, which they never did. The state was responsible for fixing the big stuff, so when the big stuff showed up the state simply kicked everybody out of the apartments without just cause eviction. You’d have situations where the building would be half empty, front doors off the hinges, the other half of the building still has people paying rent—or they would just knock down the building and make a parking lot. But they didn’t acquire anything that I’m aware of past 1976.

His role in organizing the rent strike cost Dennis a job, but he, along with the Capitol Park Renters Fund, a nonprofit organization intended to protect the rights of renters in the neighborhood, succeeded in securing greater percentages of affordable housing and restructured management of the state-owned properties in a new organization, Capitol Area Development Authority (CADA). Formed in 1978, CADA was a joint powers authority that took over management of residential properties from the private management companies, built new housing and repaired existing neighborhood housing for rental use. By 1990, population and housing in the neighborhood started to rebound. New businesses entered the neighborhood, including restaurants seeking to capture some of the growing market of state employees seeking lunch near the new state office buildings.108

Some of the vacant lots remained in use as parking, but some undemolished buildings were turned to other uses. After Sal Yniguez opened his new studio on S Street, Masako Yniguez used her experience running the coffee shop at the Belmonte Gallery to open a restaurant at 13th and O Streets named Capitol Palm. Masako specialized in healthy food, “brown rice and wheat bread,” but also served a Spam sandwich. Spam had powerful associations with California Japanese, as it was one of the most common foods supplied in the internment camps during World War II. “The first time I ate Spam was when I was in camp!” said Masako. Spam did not fit her restaurant’s health-food theme, “but I had it on really good wheat bread, so I thought that made up for it.” In another attempt to promote health, she forbade smoking inside her restaurant but set up tables outside. This brought her into conflict with Sacramento city health code inspectors, who prohibited outside seating. Masako insisted on providing outdoor seats, and eventually the code inspectors relented if she agreed to take the tables inside after 3:00 p.m.

Art Luna first arrived in Sacramento in 1965 at age thirteen. After stints dealing craps in Lake Tahoe and Reno and living in Mexico, he returned Sacramento to open Luna’s Café on 15th and N Streets in 1983. Luna’s quickly become a community center for offbeat cultural events, including art and photography shows, plays, flamenco, jazz, poetry and even stand-up comedy. “You name it, we’ve done it, even if I don’t admit it,” Art said. Luna’s also became a gathering place for the Royal Chicano Air Force, becoming a home for José Montoya’s poetry series after the Reno Club closed.109

RON MANDELLA COMMUNITY GARDEN

Land in the Capitol Area Plan boundary was purchased and cleared decades before it was needed, and when the plan changed, many lots sat vacant. One block between 14th and 15th north of Q Street became Sacramento’s first community garden. In 1971, a group of Cosumnes River College students involved in the Ecology Information Center, based at 909 12th Street, asked the California Department of General Services to temporarily lease the land. They wanted a community classroom to teach the basics of organic vegetable gardening. State officials leased the land for one dollar per year. After two years of preparation, including donations by the City of Sacramento and elected officials of tools and materials, the project opened as the Terra Firma Garden in 1974. Classes were taught by twenty-two-year-old Ron Mandella. The garden was subdivided into plots, rented for a nominal fee. Users of the garden were forbidden from using chemical fertilizers or pesticides, but the classes taught by Mandella outlined how to grow strong plants and combat pests without them. Plots in the garden rented quickly, and gardeners at Terra Firma came from all walks of life, including city council member Lloyd Connelly, and Midtown residents Sandra Good and Lynnette “Squeaky” Fromme, former members of the infamous Manson Family. Gardening converted the temporary parking lot into an urban oasis. Terra Firma’s location at 15th and Q was adjacent to Fremont Park, one of Sacramento’s city parks, and the Real Food Company organic grocery store.

On July 26, 1978, Mandella and a friend were walking along 25th Street near 4th Avenue. A car screeched around the corner, and the driver, Arthur Vela, emerged, arguing with a woman on the street, his estranged wife, Santos. Vela then returned to his car and drew a shotgun, shot Santos twice, fired at Mandella, striking him above the eye, and turned the shotgun on himself. Mandella died of the shotgun wound four days later. Vela survived and was prosecuted for both murders. The Terra Firma Garden was reorganized after Ron’s death under a new nonprofit and renamed in Ron’s memory. The garden served its intended purpose as a classroom for a generation of organic gardeners and became a rallying point for the community when volunteers fought repeated efforts to turn the garden back into a parking lot. Many of the garden’s tenants harvested produce for their own use, but much was donated to community kitchens like Food Not Bombs. Restaurant operator Julie Virga used her lot to produce locally grown herbs and vegetables. By 1987, there were two dozen community gardens in Sacramento, all inspired by the Mandella Garden’s example.110

Ron Mandella at the Terra Firma community garden, February 1978. Ron was killed a few months after this photograph was taken, and the garden was renamed in his memory. Center for Sacramento History.

FREEFORM ROCK-AND-ROLL WITH JEFF HUGHSON

Jeff Hughson, a Sacramento native born in 1950, grew up in the rock-and-roll era and was involved with the music world from age ten. From the quiet suburb of River Park, Jeff spent time with his cousin Jim Barkley, who owned IKON Recording Studio in East Sacramento. Jeff started working at IKON at age fourteen, setting up the studio for recording and unloading shipments of records. Commercial production was IKON’s stock in trade, but it also offered a deal for local bands. For $100, bands got a three-hour session, mastered quickly, and one hundred copies of a 45 RPM single.

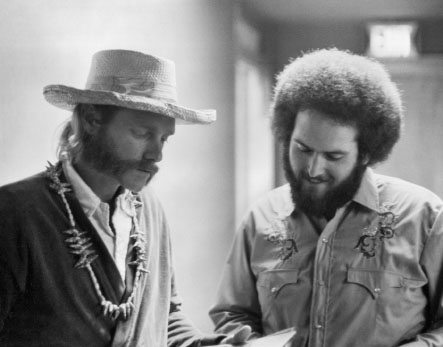

Mike Love of the Beach Boys (left) and Jeff Hughson at the KZAP five-year celebration in 1973. Center for Sacramento History.

IKON was not the only studio in town, as jazz bandleader Bill Rase had his own recording studio in South Sacramento, the Bill Rase Recording Studio and Talent Center. Small studios like IKON and Rase captured the sounds of Sacramento’s prolific bands of the early 1960s.111 Relatively few went on to great success, but these 45s served as the only record of bands that provided the soundtrack of teenage Sacramento at car club shows, social halls, school dances and psychedelic concerts in repurposed churches, theaters and city parks.

Hughson remembered:

I watched American Bandstand every day and called the disc jockeys on KROY all the time—Jack Hammer, Tony Bigg or Tony Pigg as he later became, Hal Hopkins the Emperor. I was obsessed with music, and I started going to shows when I was about fourteen or fifteen, they let me go to the auditorium. They wouldn’t let me go to the black ballroom on Fruitridge and Franklin, Coconut Grove—Little Richard played there, and they said, “No, you’re a sixteen-year-old white boy!” Just like most people of that era, they weren’t overtly racist, but they lived in suburbia. So I had to go to Little Richard on my own in Frisco. I saw James Brown Revue several times, Ike and Tina Turner, Peter Paul and Mary; Alan Sherman of Peter Paul and Mary recorded live albums at those shows. They used three venues for their recordings, Sacramento was one of them. As soon as the British Invasion started, Gary Schiro of Schiro Productions, he used to manage bands and produce surf dances. He became a big guy in town. He was president of a car club, so the car club sponsored dances and bands.

He got the Rolling Stones on their second American tour. The first American tour was about eight nights of TV shows, no live concerts. Their second tour was the first one where they played concerts, and Gary got the concert. He built a reputation with these local dances, a lot of surf dances in various locations in town. He got the Stones! And so I worked for Gary doing the same thing I did on the surf dances. He used to print 5x8 flyers with the show on the front and glue on the back. He used to pay me and a couple of other guys, and we would go around to the high schools at 10:00 at night, lick the back of these things and stick them on the metal lockers, so that the next morning, everywhere. Our tongues would just be raw, do five hundred of those in a couple of hours and buy soft drinks. So I did that for the Stones. I can remember the day of the show, Gary lived two doors down in River Park, I’m walking down Carlson and here comes this black limousine coming down the street—you don’t see that in a small community! They stopped in front of Gary’s house, and the Rolling Stones got out and had dinner! So his wife made dinner for them— whoa, the Stones are at Gary’s house! Of course the next time they came through Dick Clark got them as part of a package tour, so Gary never had a chance.

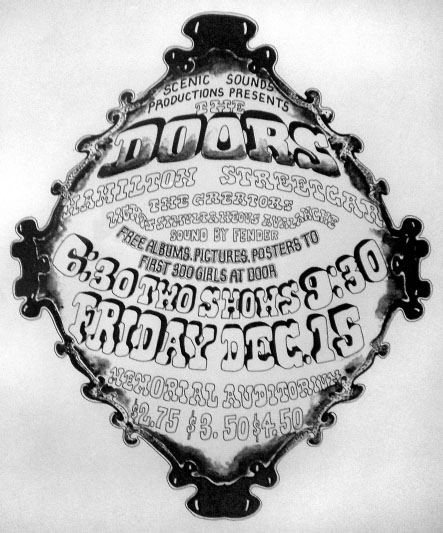

This 1967 Doors concert at Memorial Auditorium was enhanced by local psychedelic light show Simultaneous Avalanche and a poster by Sacramento artist Jim Ford. Sacramento Rock and Radio Museum.

Sacramento always had a thriving music scene because it’s a military town and there were a lot of military families. There were teenagers in these families, and the fathers had money because of working for the military…Don’t let me forget Russ Solomon! It’s the home of Tower Records. Here we have a record store dedicated to having one of every record that’s available on the market! He would buy in vast quantity, you’d see six boxes high of the latest LP, the Beatles or whatever—that nurtured this whole thing. Youth with money, it kind of fed itself. Lots of bands, lots of interest, lots of records, we had a pretty good radio station, KROY, Jack Hammar, Tony Bigg and people like that. It all fed together so there was a big music scene in town. In fact, Sacramento had a reputation as a very good music audience town, so much so that when the Rolling Stones came to Sacramento for their first American tour, two things happened. One, they played Ed Sullivan the night before on Sunday night. Monday night was Sacramento. You know how he always called the lead singer over for a chat, he did his little two or three questions, and when Jagger was done he said, “See you tomorrow night in Sacramento!” Also, when they came to Sacramento, because of buildup including KROY Radio, they got met by hundreds of teenagers at the airport, and KCRA was there and shot all this footage of screaming kids at the airport meeting the Stones as they got off the plane. The Rolling Stones purchased the footage from Channel 3, sent it back to England to show, “See how good we’re doing in America?”

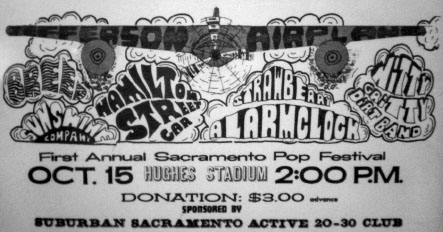

The Sacramento Pop Festival was Sacramento’s attempt at a major pop festival, featuring Jefferson Airplane and Strawberry Alarm Clock, held at Hughes Stadium, Sacramento City College. Sacramento Rock and Radio Museum.

Jeff parlayed his experience gained working for Gary Schiro into producing his own shows. Inspired by the free shows in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, he produced a series of summer shows in William Land Park in 1968 and 1969. The shows featured local and touring bands promoted on KZAP (where Jeff was the music director) and were always free events. Eventually, the shows came under pressure from local police, and Jeff was unwilling to spend his time trying to quell unruly rock concert crowds. After an incident when police showed up in riot gear, ready to raid the crowd for underage drinkers, Jeff decided that the concerts were not worth the full-time unpaid job of running them.

Jeff had plenty to keep him busy. He organized rock shows throughout Northern California and helped start legendary Sacramento radio station KZAP in 1968. At age sixteen, he already had experience as a DJ, playing the 2:00 to 6:00 a.m. shift on jazz station KXJZ and then went to school after his shift. In 1968, he joined forces with Lee Gahagan and others interested in starting a free-form radio station in Sacramento and became KZAP’s first general manager, based on his radio experience and extensive musical knowledge at eighteen years old. KZAP’s first broadcast studio was at the top of the Elks Building at 11th and K, the same space as the Top of the Town jazz club, but by 1972, it had moved to a new office at 9th and J Streets. Several KZAP DJs, including Gary, lived in a Midtown Victorian simply known as “KZAP House” at 22nd and N Streets.

KZAP DJ and rock concert promoter Jeff Hughson relaxes at Lake Amador Gold Rush Rock Festival, October 4, 1969. Jeff Hughson.

Sacramento’s counterculture brought people back to the central city, moving into the surviving Victorian homes. Rick Ball, a partner in the Beginning, purchased a home on 20th and N Streets, moving out of the back of the shop. Rick was known as an eccentric character even among the hippie scene who gave each of his household appliances a name and dressed them in clothes. He expanded the home with a second story, intended as his brass workshop, with a turret containing a spiral staircase and a secret passage to the top of a turret, where Rick liked to smoke marijuana and watch the sky. Rick had just finished restoring the house when he died of a brain aneurysm in his twenties. More like-minded young people were drawn to the Old City, and by the mid-1970s, many of the decaying Victorians on Suttertown’s tree-lined streets had new coats of paint, newly restored interiors and new inhabitants looking for a new way of life.

Rick Ball in the lot between the Beginning and Mario’s Italian Cellar. The Beginning got enough bike traffic to justify this handmade bicycle rack. Snow is a very rare event in Sacramento, but bicycles were becoming more common. Mickey Abbey.